Colonialism and Nineteenth-Century Flooding of Ojibwa Lands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Ruth Landes Papers, 1928-1992

Guide to the Ruth Landes papers, 1928-1992 John Glenn and Lorain Wang The revision of this finding aid and digitization of portions of the collection were made possible through the financial support of the Ruth Landes Memorial Research Fund. 1992, 2010 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 8 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 4 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 7 Bibliography: Books......................................................................................................... 8 Bibliography: Articles and Essays................................................................................... 9 Bibliography: Book Reviews.......................................................................................... 10 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................... 11 Container Listing .......................................................................................................... -

North Western Ontario

N O R T H W E S T E R N O NT A R I O : B O U ND A R E S R E S O U R C E S C O MMU NI C A T I O N S . PR E PA R E D U ND E R I NS T R U C T I O NS F R O M T HE finruutu PR I N 2 5 WE L L I NGT O N S T E E T WE S T T E D NT E R O S E C O . B Y HU . R , R 1 879 . T A B L E OF C ONT E NT S. Agr icult ural C ap acit y E R R A T A . i r ea sou r ce of t he s a d e . 1 6 fo r s out h of t he s aid rive r d riv r n a e 2 in , O p g , l e amy ak a oot for a n E l e ea ge 3 fou r th l n e f o f , R R L O n p a , i r m i y v r r” d o et t e en t s ecomi hu e , er he a I n ce en t s t S , O n p age 7 u n d d du m l m ” r n west e . ” 13 1 11 hu e ea h e s on a n d on 5 , ¢h\ age 2 fir s : ime for Y o , O n p 7 , , rk r d l ’ east e n . -

Water Management of the Steep Rock Iron Mines at Atikokan, Ontario During Construction, Operations, and After Mine Abandonment

Proceedings of the 25th Annual British Columbia Mine Reclamation Symposium in Campbell River, BC, 2001. The Technical and Research Committee on Reclamation WATER MANAGEMENT OF THE STEEP ROCK IRON MINES AT ATIKOKAN, ONTARIO DURING CONSTRUCTION, OPERATIONS, AND AFTER MINE ABANDONMENT V. A. Sowa, P. Eng., F.E.I.C. 1 R. B. Adamson, P. Eng.2 A.W. Chow, P. Eng.3 1 Jacques Whitford and Associates Limited, Vancouver, British Columbia 2 Adamson Consulting, Thunder Bay, Ontario 3 Northwest Region, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Thunder Bay, Ontario ABSTRACT The Steep Rock Iron Mines at Atikokan, Ontario operated from 1944 to 1979. The iron ore was located at the bottom of Steep Rock Lake and water management was a key factor in developing the mines. Open pit mining required a massive water diversion scheme, including the diversion of the Seine River, draining of Steep Rock Lake, and construction of various dams and other diversion structures. In order to abandon the mine, the Province of Ontario required a suitable abandonment and long-term water management plan, and assessment of the condition of the various water control and diversion structures. Reclamation of the Seine River to its original course was not possible and, consequently, the water control structures, primarily dams and tunnels, will be operating in perpetuity. The water management during the development of the mines and during operations is described, as well as some insight into future water management options after abandonment. INTRODUCTION The richest undeveloped deposit of hematite iron ore on the North American continent at the time was discovered in 1938 beneath Steep Rock Lake, near Atikokan, Ontario. -

Community Strategic Plan 2011 - 2016

LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION THE COMMUNITY OF NEZAADIIKAANG The Place of Poplars COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN 2011 - 2016 Prepared by Meyers Norris Penny LLP LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION THE COMMUNITY OF NEZAADIIKAANG COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation Contact: Chief and Council c/o Quentin Snider, Band Manager Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation Thunder Bay, ON P7B 4A3 MNP Contacts: Joseph Fregeau, Partner Kathryn Graham, Partner Meyers Norris Penny LLP MNP Consulting Services 315 Main Street South 2500 – 201 Portage Avenue Kenora, ON P9N 1T4 Winnipeg, MB R3B 3K6 807.468.1202 204.336.6243 [email protected] [email protected] LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION THE COMMUNITY OF NEZAADIIKAANG COMMUNITY STRATEGIC PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 2 Context for Community Strategic Planning ................................................................................................... 3 Past Plan ................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Process .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Membership -

District of Rainy River Community Profile & Demographics

District of Rainy River Community Profile & Demographics January 2021 Prepared by: Rainy River Future Development Corporation District of Rainy River Contents Community Futures Development Corporation ............................................................... 3 Natural Resources........................................................................................................... 5 Strategic Location ........................................................................................................... 6 Levels of Government ..................................................................................................... 7 Municipal Contact Information ......................................................................................... 7 Regional First Nation Communities ................................................................................. 8 Regional Chambers of Commerce .................................................................................. 9 Education ...................................................................................................................... 10 Educational Institutions ................................................................................................. 11 Rainy River District Schools .......................................................................................... 12 Telecommunications ..................................................................................................... 15 Utilities .......................................................................................................................... -

Building Green Energy Initiatives in Northern Ontario Indigenous Communities: Case Study on Community Development in Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Undergraduate theses 2020 Building green energy initiatives in Northern Ontario Indigenous communities: case study on community development in Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation Berkan, Judah http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/4617 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons BUILDING GREEN ENERGY INITIATIVES IN NORTHERN ONTARIO INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES: CASE STUDY ON COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION by Judah Berkan FACULTY OF NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT LAKEHEAD UNIVERSITY THUNDER BAY, ONTARIO April 10, 2020 BUILDING GREEN ENERGY INITIATIVES IN NORTHERN ONTARIO INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES: CASE STUDY ON COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT IN LAC DES MILLE LACS FIRST NATION by Judah Berkan An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Honours Bachelor of Science in Forestry Faculty of Natural Resources Management Lakehead University ------------------------------------------ ----------------------------------- Dr. Chander Shahi Laird Van Damme, R.P.F. Major Advisor Second Reader 2 LIBRARY RIGHTS STATEMENT In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the HBScF degree at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay. I agree that the University will make it freely available for inspection. This thesis is made available by my authority solely for the purpose of private study and research and may not be copied or reproduced in whole or in part (except as permitted by the Copyright Laws) without my written authority. Date: _____________________________04/21/2020 2 A CAUTION TO THE READER This HBScF thesis has been through a semi-formal process of review and comment by at least two faculty members. It is made available for loan by the Faculty of Natural Resources Management for the purpose of advancing the practice of professional and scientific forestry. -

Table of Contents

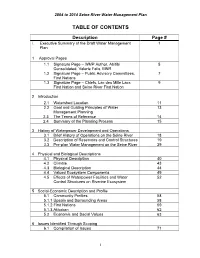

2004 to 2014 Seine River Water Management Plan _________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS Description Page # i. Executive Summary of the Draft Water Management 1 Plan 1 Approval Pages 1.1 Signature Page – WMP Author, Abitibi 5 Consolidated, Valerie Falls, MNR 1.2 Signature Page – Public Advisory Committees, 7 First Nations 1.3 Signature Page – Chiefs, Lac des Mille Lacs 9 First Nation and Seine River First Nation 2 Introduction 2.1 Watershed Location 11 2.2 Goal and Guiding Principles of Water 13 Management Planning 2.3 The Terms of Reference 14 2.4 Summary of the Planning Process 15 3 History of Waterpower Development and Operations 3.1 Brief History of Operations on the Seine River 18 3.2 Description of Reservoirs and Control Structures 19 3.3 Pre-plan Water Management on the Seine River 29 4 Physical and Biological Descriptions 4.1 Physical Description 40 4.2 Climate 43 4.3 Biological Description 44 4.4 Valued Ecosystem Components 49 4.5 Effects of Waterpower Facilities and Water 52 Control Structures on Riverine Ecosystem 5 Social-Economic Description and Profile 5.1 Community Profiles 58 5.1.1 Upsala and Surrounding Areas 58 5.1.2 First Nations 59 5.1.3 Atikokan 62 5.2 Economic and Social Values 63 6 Issues Identified Through Scoping 6.1 Compilation of Issues 71 i 2004 to 2014 Seine River Water Management Plan _________________________________________________________________ 6.2 Spatial & Temporal Assessment 79 6.3 Issues not addressed in Planning 80 7 Plan Objectives 7.1 Developing the Objectives -

*“Residual Transcriptions: Ruth Landes and the Archive of Conjure,” Transforming Anthropology April 2018, 26(1): 3-17

CURRICULUM VITAE: SOLIMAR OTERO, PH.D. Contact Information: 260 Allen Hall Baton Rouge, LA 70803 (225) 578 – 3046 CURRICULUM VITAE [email protected] SOLIMAR OTERO, PH.D. ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY I. EDUCATION 2002 Ph.D., Folklore and Folklife, University of Pennsylvania. 1997 M.A., Folklore and Folklife, University of Pennsylvania. 1994 B.A., Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, (Suma Cum Laude). II. RECENT PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2017-present Director, LSU Program in Comparative Literature. 2005–present Associate Professor, English, Louisiana State University. 2015 –present Director, Program in Louisiana and Caribbean Studies, LSU. 2016 - 2017 Director, Summer Study Abroad Program, Ogden Honors College, LSU. 2014 Spring semester, Associate Chair, Department of English. 2009–2010 Visiting Research Associate and Assistant Professor of Folklore and Afro-Atlantic Religion, Harvard Divinity School, Women in Religion Program, Cambridge. III. GRANTS AND AWARDS (EXCERPT) 2018 LSU Distinguished Faculty Award 2017 Manship Summer Research Grant 2015 Regents Research Grant, LSU, Fall 2015. 2014 Manship Summer Research Grant, LSU, College of Humanities and Social Sciences. 2013 H.M. “Hub” Cotton Award for Faculty Excellence, Louisiana State University. 2013 Ruth Landes Memorial Research Fund Fellowship, Research in Cuba and at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 2012 Sabbatical Research Award, LSU, for research at the Lydia Cabrera Papers, Cuban Heritage Collection, University of Miami, Miami, Florida. 2009–2010 Research Associate and Visiting Faculty, Women’s Studies in Religion Program, Harvard Divinity School, 2009-2010 academic year. 2007 PI, Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Outreach Grant, Louisiana Folklore Society Meeting. 2000 - 2001 Fulbright IIE Grant for Research in Nigeria. -

A Guide for Working with Aboriginal People of Northwestern Ontario Condensed Version

A Guide for Working with Aboriginal People of Northwestern Ontario Condensed Version A Stroke Resource for Healthcare Providers NORTHWESTERN ONTARIO A Stroke Resource for Healthcare Providers 1 Map of Treaties and Health Facilities A Guide for Working with Aboriginal Fort Severn People of Northwestern Ontario A Stroke Resource for Healthcare Providers Legend No rth West LHIN Nursing Stations / Health Facility Ontario Breast Screening Program Manitoba Friendship Centres No rth East LHIN Aboriginal Health Access Centres Hospitals Preface Big Trout Lake Metis Consultation Wapekeka LHIN Boundary Sachigo Lake Bearskin Lake Kasabonika Lake My dad once said “The White medicines. And yet another group Wawakapewin Webequie Muskrat Dam people were given the gift of their may decide to use Aboriginal Koocheching Kingfisher Lake James Bay Sandy Lake Kee-W ay-Win North Caribou Lake Nibinamik medicines. We were also given the medicines only. The last group will Treaties Wunnummin Weagamow Lake gift to know our medicines. Do not use non-Aboriginal medicines. What North Spirit Lake Robinson-Superior: 1850 Deer Lake Whitewater Lake reject either one. Both are good”. is common among the group is Tr eaty #3: 1873 McDowell Lake Poplar Hill they are seeking to be healthy in all Tr eaty #5: 1875-76 Cat Lake My dad was a wise, humble and Lansdowne House aspects of their lives. So, I believe Tr eaty #9: 1905-06Shoal Lak Pikangikum loving human being. My dad was in Slate Falls Pickle Lake Marten Falls all the medicines are all equally Tr eaty #9: 1929-30 Fort Hope his late 90’s when he passed away. -

Basque Studies Newsletter ISSN: 1537-2464 Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R

Center for Basque Studies Newsletter ISSN: 1537-2464 Center for Basque Studies N E W S L E T T E R An Interview with 2009-2010 Douglass Scholar Santiago de Pablo Fall Vitoria, October 6, 2010. University of the Basque Country 2010 By Oscar Álvarez Gila. Oscar: Let’s start by getting to know you. NUMBER 78 photo: L. Corcostegui Could you give us a brief summary of your life experience and your career as a In this issue: historian? (Earth Without Peace. Civil War, Film and Propaganda in the Basque Country, Madrid, Santi: I was born in 1959 in Tabuenca, Biblioteca Nueva, 2006) in which I explore Santi de Pablo Interview 1 a small town in Aragon, near southern the use of film for the dissemination of propaganda during the Civil War in Euskadi. Oscar Álvarez 3 Navarra, where my father worked as a doctor. When I was seven years old my I have also organized an annual conference, Co-Directors’ Message 3 family moved to Vitoria-Gasteiz and, except History through Cinema, since 1998 in Vitoria, and I am a member of the Academy of Publications Coordinator for three years in which I studied at the 4 University of Navarra, my career has always Motion Picture Arts and Sciences of Spain. Lehendakari Visit 4 been linked to the capital of Alava and Euskadi. With regard to Basque contemporary history, I Current Research 5 would mention my books Los problemas de la 2010 Conference 6 In 1987 I obtained a Ph.D. in History from autonomía vasca en el siglo XX (Problems of the University of the Basque Country, Basque Autonomy in the Twentieth Century) Highlights 7 where I’ve been employed since then: (Oñate, MVI, 1991), Trabajo, diversión y vida Bieter Grant 8 first in the School of Social Sciences and cotidiana. -

2021 Atikokan Crown Land Route Book

2021 Atikokan Crown Land Route Book You are receiving this document because your crew has chosen to paddle in the Crown Lands or you are a crew of 9 to 11 people which can only travel in the Crown Lands. The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources requires a route selection well in advance of your trip. You must select your preferred route by the day your final payment is due so that we may submit it to the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) with enough notice for your trip. Canada is comprised of 89% Crown Land. It is all un-owned land, coast to coast in Canada. Locals refer to the area we paddle simply as “the Bush.” The routes in this document allow us to better accommodate your crew and give our Interpreters a general idea of where you want to travel so they may plan accordingly. Please review this document with your crew and make your route selection. When you arrive at the Atikokan base, your crew and Interpreter will have time to decide the specifics of your trip ranging from daily distances, where you’ll camp each night, and options to extend or shorten certain sections of your route. While the exact route may have some flexibility, assigned entry points and exit points will not change and major route edits must be pre-approved. The day length in each section is to be used as a guideline. They do not need to be strictly adhered to. For example, if your crew wants to paddle more distance, they can select a route that suggests more days. -

2019 NWO Side Map Layout 1

KILOMETERS Shortest Distance calculated from THUNDER BAY (KM) IN CANADA Municipal KILOMETERS Thunder Bay KEY X 0.62 = MILES CAMPGROUNDS MILES IN USA MILES X 1.6 = KILOMETERS CHIPPEWA PARK 11 17 Provincial Highway Picnic Area KOA Secondary Highway Golf Course 8076233912 On Trans Canada Highway 1117 just 2 Local, independant, community magazine distributes Located on the shore of the world’s largest Provincial Park, one of Canada’s great natural X 213 416 150 702 460 516 826 172 367 486 301 428 895 391 254 1186 406 206 435 214 665 579 17 Trans Canada Highway Summer Activities miles East of the Terry Fox Monument, 36,000 copies annually to businesses and properties. freshwater lake and nestled among Canada’s wonders, a gateway to the Lake Superior National 213 X 454 188 850 404 460 610 106 137 634 449 216 1043 537 98 1334 552 354 498 212 813 351 turn towards Lake Superior at Spruce TROWBRIDGE Ontario Provincial Park Winter Activities while still carrying CN logos as well. 416 454 X 266 819 235 178 581 533 481 604 418 668 671 509 552 977 523 306 45 425 782 663 River Rd. Follow signs. boreal forests and Canadian Shield. The city has Marine Conservation Area, Quetico Park and tens 150 188 266 X 843 500 395 605 293 216 628 443 406 533 286 932 1236 547 348 310 356 806 357 FALLS That September, Via published a 702 850 819 843 X 585 641 248 744 1004 327 402 826 488 875 769 557 401 520 775 637 325 1217 RV sites are tucked in the trees Airport Wilderness or single timetable with information on 8076836661 everything you need to get outfitted properly for of thousands of great angling lakes and thousands In the 1970s CN sought to rid itself of 460 404 235 500 585 X 57 347 298 541 370 185 619 771 274 429 1071 288 72 191 192 548 754 and in the wideopen sunshine.