Hamish Adams Evidence 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Monday, 2Oth

No. 48346 14607 SUPPLEMENT TO of Monday, 2oth Registered as a Newspaper TUESDAY, 21ST OCTOBER 1980 MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Major David Alan HODGENS (481798), Royal Army HONOURS AND AWARDS Ordnance Corps. 23697563 Warrant Officer Class I (now Lieutenant) CENTRAL CHANCERY OF William Philip KENT, Royal Corps of Signals. THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD Major Angus David Ian WALL (477853), Welsh Guards. St James's Palace, London S.W.I. 21st October 1980 CENTRAL CHANCERY OF The QUEEN has been graciously pleased to give orders for THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD the following promotions in, and appointments to, the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in recognition of St James's Palace, London S.W.I. distinguished services in Northern Ireland during the period 21st October 1980 1st February 1980 to 30th April 1980: The QUEEN has been graciously pleased to approve the To be Additional Commanders of the Military award of The George Medal in recognition of outstanding Division of the said Most Excellent Order : bravery in Northern Ireland during the period 1st Feb- Brigadier David John RAMSBOTHAM, O.B.E. (427439), ruary 1980 to 30th April 1980: late The Royal Green Jackets. 24315425 Sergeant (now Acting Staff Sergeant) John Brigadier Colin Terry SHORTIS, O.B.E. (426767), late Anthony ANDERSON, Royal Army Ordnance Corps. The Devonshire and Dorset Regiment. To be Additional Officers of the Military Division of the said Most Excellent Order : CENTRAL CHANCERY OF Lieutenant-Colonel (now Acting Colonel) Peter FOR- THE ORDERS OF KNIGHTHOOD SHAW (444529), Royal Army Ordnance Corps. St. James's Palace, London S.W.1. -

Nepal, November 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Nepal, November 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: NEPAL November 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Kingdom of Nepal (“Nepal Adhirajya” in Nepali). Short Form: Nepal. Term for Citizen(s): Nepalese. Click to Enlarge Image Capital: Kathmandu. Major Cities: According to the 2001 census, only Kathmandu had a population of more than 500,000. The only other cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were Biratnagar, Birgunj, Lalitpur, and Pokhara. Independence: In 1768 Prithvi Narayan Shah unified a number of states in the Kathmandu Valley under the Kingdom of Gorkha. Nepal recognizes National Unity Day (January 11) to commemorate this achievement. Public Holidays: Numerous holidays and religious festivals are observed in particular regions and by particular religions. Holiday dates also may vary by year and locality as a result of the multiple calendars in use—including two solar and three lunar calendars—and different astrological calculations by religious authorities. In fact, holidays may not be observed if religious authorities deem the date to be inauspicious for a specific year. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Sahid Diwash (Martyrs’ Day; movable date in January); National Unity Day and birthday of Prithvi Narayan Shah (January 11); Maha Shiva Ratri (Great Shiva’s Night, movable date in February or March); Rashtriya Prajatantra Diwash (National Democracy Day, movable date in February); Falgu Purnima, or Holi (movable date in February or March); Ram Nawami (Rama’s Birthday, movable date in March or April); Nepali New Year (movable date in April); Buddha’s Birthday (movable date in April or May); King Gyanendra’s Birthday (July 7); Janai Purnima (Sacred Thread Ceremony, movable date in August); Children’s Day (movable date in August); Dashain (Durga Puja Festival, movable set of five days over a 15-day period in September or October); Diwali/Tihar (Festival of Lights and Laxmi Puja, movable set of five days in October); and Sambhidhan Diwash (Constitution Day, movable date in November). -

Brigade of Gurkha - Intake 1983 Souvenir

BRIGADE OF GURKHA - INTAKE 1983 SOUVENIR [ A Numberee’s Organization ] -: 1 :- BRIGADE OF GURKHA - INTAKE 1983 SOUVENIR ;DkfbsLo !(*# O{G6]ssf] ofqf #% jif]{ ns]{hjfgaf6 #^ jif{ k|j]z cfhsf] @! cf} ztflAbdf ;dfhdf lzIff, ;jf:Yo, snf, ;:sf/, ;+:s[lt, ;dfrf/ / ;+u7gn] ljZjsf] ab\lnbf] kl/j]zdf ;+ul7t dfWodsf] e"ldsf ctL dxTjk"0f{ /x]sf] x'G5 . To;}n] ;+ul7t If]qnfO{ ljsf;sf] r'r'/f]df klxNofpg] ctL ;s[o dgf]efj /fvL ;dfhdf /x]sf ljz'4 xs / clwsf/ sf] ;+/If0f ;Da4{g ub}{, cfkm\gf] hGdynf] OG6]s ;d'bfodf cxf]/fq nflu/x]sf] !(*# O{G6]sn] #% jif{sf] uf}/jdo O{ltxf; kf/ u/]/ #^ jif{df k|j]z u/]sf] z'e–cj;/df ;j{k|yd xfd|f ;Dk"0f{ z'e]R5'sk|lt xfdL cfef/ JoQm ub{5f}+ . !(*# OG6]ssf] aRrfsf] h:t} afd] ;g]{ kfO{nf z'? ePsf] cfh #^ jif{ k|j]z ubf{;Dd ;+;f/el/ 5l/P/ a;f]af; ul//x]sf gDa/L kl/jf/ ;dIf o:tf] va/ k|:t't ug{ kfp“bf xfdL ;a}nfO{ v'zL nfUg' :jfefljs g} xf] . ljutsf] lbgnfO{ ;Dem]/ Nofpg] xf] eg] sxfnLnfUbf] cgL ;f]Rg} g;lsg] lyof], t/ Psk|sf/sf] /f]rs clg k|;+usf] :d/0f ug{'kg]{ x'G5 . ha g]kfndf a9f] d'l:sNn} etL{ eP/ cfdL{ gDa/ k|fKt ug{' eg]sf] ax't\ sl7g cgL r'gf}ltk"0f{ sfo{ lyof] . z'elrGtssf] dfof / gDa/Lx?sf] cys kl/>daf6 !(*# O{G6]ssf] Pstf lg/Gt/ cufl8 a9L/x]sf] 5, of] PstfnfO{ ;d[4 agfpg] sfo{df sld 5}g, To;}n] #^ jif{;Ddsf] lg/Gt/ ofqfnfO{ ;fy lbP/ O{G6]snfO{ cfkm\gf] 9's9'sL agfpg] tdfd dxfg'efjk|lt xfdL C0fL 5f}+ . -

![Aldershot Command (1937)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7582/aldershot-command-1937-497582.webp)

Aldershot Command (1937)]

7 September 2018 [ALDERSHOT COMMAND (1937)] Aldershot Command Regular Troops in the District st 1 Cavalry Brigade (1) The Queen’s Bays (2nd Dragoon Guards) The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons) 4th Queen’s Own Hussars 3rd Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery (H.Q., ‘D’, ‘J’ & ‘M’ Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) ‘D’ Troop, Mobile Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals st 1 Anti-Aircraft Group (2) 4th Anti-Aircraft Brigade, Royal Artillery (H.Q., 16th, 18th & 20th Anti-Aircraft Batteries and 3rd Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Royal Artillery) 6th Anti-Aircraft Brigade, Royal Artillery (H.Q., 3rd, 12th & 15th Anti-Aircraft Batteries and 1st Light Anti-Aircraft Battery, Royal Artillery) 1st Anti-Aircraft Battalion, Royal Engineers (‘A’ & ‘B’ Anti-Aircraft Companies, Royal Engineers) 2nd Anti-Aircraft Battalion, Royal Engineers 1st Anti-Aircraft Group Signals, Royal Corps of Signals 2nd Anti-Aircraft Group Signals, Royal Corps of Signals Unbrigaded Troops nd 2 Bn. The Royal Irish Fusiliers (Princess Victoria’s) (3) nd 2 Bn. Royal Tank Corps (4) th 4 (Army) Bn. Royal Tank Corps (4) Mechanical Warfare Experimental Establishment, Royal Tank Corps (4) II Field Brigade, Royal Artillery (5) (H.Q., 35th (Howitzer), 42nd, 53rd & 87th Field Batteries, Royal Artillery) nd 2 Medium Brigade, Royal Artillery (6) (H.Q., 4th, 7th (Howitzer), 8th (Howitzer) & 12th (Howitzer) Medium Batteries, Royal Artillery) © www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 7 September 2018 [ALDERSHOT COMMAND (1937)] Royal Engineers (7) Regimental Headquarters and Mounted Depot, Royal Engineers 1st (Field) Squadron, Royal Engineers 8th (Railway) Squadron, Royal Engineers 10th (Railway) Squadron, Royal Engineers Royal Corps of Signals (8) ‘A’ Corps Signals, Royal Corps of Signals No. -

Constructing a Gurkha Diaspora

Ethnic and Racial Studies ISSN: 0141-9870 (Print) 1466-4356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20 Migrant warriors and transnational lives: constructing a Gurkha diaspora Kelvin E. Y. Low To cite this article: Kelvin E. Y. Low (2015): Migrant warriors and transnational lives: constructing a Gurkha diaspora, Ethnic and Racial Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1080377 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1080377 Published online: 23 Sep 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rers20 Download by: [NUS National University of Singapore] Date: 24 September 2015, At: 00:24 ETHNIC AND RACIAL STUDIES, 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1080377 Migrant warriors and transnational lives: constructing a Gurkha diaspora Kelvin E. Y. Low Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore ABSTRACT The Nepalese Gurkhas have often been regarded as brave warriors in the scheme of British military recruitment since the 1800s. Today, their descendants have settled in various parts of South East and South Asia. How can one conceive of a Gurkha diaspora, and what are the Gurkhas and their families’ experiences of belonging in relation to varied migratory routes? This paper locates Gurkhas as migrants by deliberating upon the connection between military service and migration paths. I employ the lens of methodological transnationalism to elucidate how the Gurkha diaspora is both constructed and experienced. Diasporic consciousness and formation undergo modification alongside subsequent cycles of migration for different members of a diaspora. -

ARF Annual Security Outlook 2020

Table of Contents Foreword 5 Executive Summary 7 Australia 9 Brunei Darussalam 25 Cambodia 33 Canada 45 China 65 European Union 79 India 95 Indonesia 111 Japan 129 Lao PDR 143 Malaysia 153 Mongolia 171 Myanmar 179 New Zealand 183 The Philippines 195 Republic of Korea 219 Russia 231 Singapore 239 Sri Lanka 253 Thailand 259 United States 275 Viet Nam 305 ANNUAL SECURITY OUTLOOK 2020 ASEAN Regional Forum 4 ANNUAL SECURITY OUTLOOK 2020 ASEAN Regional Forum FOREWORD Complicated changes are taking place in the regional and global geostrategic landscape. Uncertainties and complexities have been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. We are deeply saddened by the loss of lives and sufferings caused by this dreadful pandemic. Nevertheless, we are determined to enhance solidarity and cooperation towards effective efforts to respond to the pandemic as well as prevent future outbreaks of this kind. Since its founding in 1994, the ARF has become a key and inclusive Forum working towards peace, security and stability in the region. Through its activities, the ARF has made notable progress in fostering dialogue and cooperation as well as mutual trust and confidence among the Participants. In face of the difficulties and challenges brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, ARF Participants have exerted significant efforts to sustain the momentum of dialogue and cooperation, while moving forward with new proposals and initiatives to respond to existing and emerging challenges. At this juncture, it is all the more important to reaffirm the ARF as a key venue to strengthen dialogue, build strategic trust and enhance practical cooperation among its Participants. -

Wire August 2013

THE wire August 2013 www.royalsignals.mod.uk The Magazine of The Royal Corps of Signals HONOURS AND AWARDS We congratulate the following Royal Signals personnel who have been granted state honours by Her Majesty The Queen in her annual Birthday Honours List: Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) Maj CN Cooper Maj RJ Craig Lt Col MS Dooley Maj SJ Perrett Queen’s Volunteer Reserves Medal (QVRM) Lt Col JA Allan, TD Meritorious Service Medal WO1 MP Clish WO1 PD Hounsell WO2 SV Reynolds WO2 PM Robins AUGUST 2013 Vol. 67 No: 4 The Magazine of the Royal Corps of Signals Established in 1920 Find us on The Wire Published bi-monthly Annual subscription £12.00 plus postage Editor: Mr Keith Pritchard Editor Deputy Editor: Ms J Burke Mr Keith Pritchard Tel: 01258 482817 All correspondence and material for publication in The Wire should be addressed to: The Wire, RHQ Royal Signals, Blandford Camp, Blandford Forum, Dorset, DT11 8RH Email: [email protected] Contributors Deadline for The Wire : 15th February for publication in the April. 15th April for publication in the June. 15th June for publication in the August. 15th August for publication in the October. 15th October for publication in the December. Accounts / Subscriptions 10th December for publication in the February. Mrs Jess Lawson To see The Wire on line or to refer to Guidelines for Contributors, go to: Tel: 01258 482087 http://www.army.mod.uk/signals/25070.aspx Subscribers All enquiries regarding subscriptions and changes of address of The Wire should be made to: 01258 482087 or 94371 2087 (mil) or [email protected]. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 20 SEPTEMBER, 1945 Captain (Temporary) Henry George WHITE (97571), No

4674 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 20 SEPTEMBER, 1945 Captain (temporary) Henry George WHITE (97571), No. 5504222 Sergeant James William HARE, The Roj-aJ. Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. •Hampshire Regiment (London, N.7). No. ',.870590 Warrant Officer Class II Clifford No. 83050 Corporal George Robert James HARVEY, Ar:lribald WHITING, Corps of Royal Engineers c^iNew Zealand Military Forces. (Stroud). No. 6769162 Sergeant Cyril Victor HEARN, Corps of Major (temporary) Reginald Henry WHITWORTH Military Police (New Maiden). (124539), Grenadier Guards (Penhope, Worcs). No. 897749 Staff-Sergeant John Allen HOWARTH, Captain (acting Howard Aubrey WILLIAMS (174782), Royal Regiment of Artillery (Manchester). Corps of Royal Engineers (Cowbridge). No.' 6137113 Warrant Officer Class I (acting) James Major (temporary) Edward Sidney WILLIS (105858), Henry HOWARTH, Corps of Military Police Royal Corps of Signals (Brighton, 7). (Harrow). Major Henry Moores WITHERSPOON (n877oV), South No. 8/6026454 Sergeant Henry Robert HOWE, Royal African Forces. Army Service Corps (Benfleet). Captain (temporary) Eric WOOD (179553), Royal No. 2593731 Corporal Stanley Frederick IBBOTSON, Army Service Corps (Huddersfield). Royal Corps of Signals (Knaresborough). Lieutenant-Colonel (local) Geoffrey WRIGHT (72469), No. RH/2329347 Sergeant Basil William IRWIN, Royal Regiment of Artillery (Tettenhall). Sq$$h African Forces. No. 6780671 Warrant Officer Class I Henry Thomas No. 1709693 Bombardier Herbert Samuel JAKE WAY, WRIGHT, Corps of Military Police (London, S.E-5). Royal Regiment of Artillery (Oldham). Major (temporary) Richard YATES (53211), Royal No. 2339348 Sergeant Walter James JELLY., Royal Tank Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps (Leeds). Corps of Signals (Guildford). Major (temporary) .Laurence McLellan YOUNG, M.C. No. 2733952 Sergeant William John JONES, Welsh (7^635), Corps of Royal Engineers (Bridge-of- Guards (Esher). -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, I JANUARY, 1944

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, i JANUARY, 1944. No. 3183342 Colour-Sergeant (Company Private Frank George Walden, Kent Home Quartermaster-Sergeant) Adam Redpath, The Guard. King's Own Scottish Borderers. No. 7259898 Staff-Sergeant Albert Warburton, No. 2993484 Sergeant Thomas Forrest Rennie, Royal Army Medical Corps. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders No. 6573033 Battery Quartermaster-Sergeant (Princess Louise's). ' Henry Nathan Ward, Royal Artillery. No. 170334 Sergeant-Instructor Stanley George No. 5046640 Sergeant (acting Company Rider, Royal Army Service Corps (since Sergeant-Major) John West, The North Staf- transferred to Army Physical Training fordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's). Corps). No. 825166 Sapper Alfred Whitfield, Royal Sergeant William Roberts, Denbighshire Home Engineers. Guard. No. 4798777 Private Bernard Wigglesworth, The No. W/16859 Sergeant Vera Estella Rothwell, Lincolnshire Regiment. Auxiliary Territorial Service. No. 1485019 Staff-Sergeant (acting Battery No. 7110733 Sergeant Thomas Ryan, The Quartermaster - Sergeant) Edward Joseph. King's Shropshire Light Infantry. Wigley, Royal Artillery. No. 4070157 Bombardier (Lance-Sergeant) No. 7582902 Corporal Albert Edward Wolland, Frederick Saunders, Royal Artillery. The King's Royal Rifle Corps. Sergeant Douglas Owen Scrace, Kent Home Sergeant Gordon Woods, Warwickshire Home- Guard. Guard. No. 2045679 Bombardier (Lance-Sergeant) No. W/2HI2 Staff-Sergeant Phyllis Kate William Henry Arthur Scudder, Royal Worrow, Auxiliary Territorial Service. Artillery. No. 4857440 Sergeant Ernest Sharpe, The The KING has been graciously pleased, on Leicestershire Regiment. the advice of His Majesty's Australian Corporal Bernard Arthur Shaw, Derbyshire Ministers, to approve the award of the British Home Guard. Empire Medal (Military Division) to the under- No. MT / 905410 Havildar Shy am Datt, Royal mentioned : — Indian Army Service Corps. -

Information Regarding the Appointment of All Honorary Colonels in the British Army

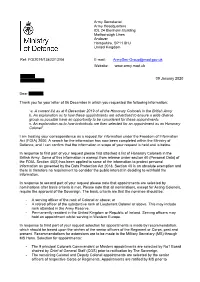

Army Secretariat Army Headquarters IDL 24 Blenheim Building Marlborough Lines Andover Hampshire, SP11 8HJ United Kingdom Ref: FOI2019/13423/13/04 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.army.mod.uk XXXXXX 09 January 2020 xxxxxxxxxxxxx Dear XXXXXX, Thank you for your letter of 06 December in which you requested the following information: “a. A current list as at 6 December 2019 of all the Honorary Colonels in the British Army b. An explanation as to how these appointments are advertised to ensure a wide diverse group as possible have an opportunity to be considered for these appointments c. An explanation as to how individuals are then selected for an appointment as an Honorary Colonel” I am treating your correspondence as a request for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. A search for the information has now been completed within the Ministry of Defence, and I can confirm that the information in scope of your request is held and is below. In response to first part of your request please find attached a list of Honorary Colonels in the British Army. Some of this information is exempt from release under section 40 (Personal Data) of the FOIA. Section 40(2) has been applied to some of the information to protect personal information as governed by the Data Protection Act 2018. Section 40 is an absolute exemption and there is therefore no requirement to consider the public interest in deciding to withhold the information. In response to second part of your request please note that appointments are selected by nominations after basic criteria is met. -

![1 Armoured Division (1939)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1499/1-armoured-division-1939-1901499.webp)

1 Armoured Division (1939)]

1 May 2019 [1 ARMOURED DIVISION (1939)] st 1 Armoured Division (1) Headquarters, 1st Armoured Division st 1 Light Armoured Brigade (2) Headquarters, 1st Light Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 1st King’s Dragoon Guards 3rd The King’s Own Hussars 4th Queen’s Own Hussars nd 2 Light Armoured Brigade (3) Headquarters, 2nd Light Armoured Brigade & Signal Section The Queen’s Bays (2nd Dragoon Guards) 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers 10th Royal Hussars (Prince of Wales’s Own) st 1 Heavy Armoured Brigade (4) Headquarters, 1st Heavy Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Royal Tank Regiment 3rd Royal Tank Regiment 5th Royal Tank Regiment st 1 Support Group (5) 2nd Bn. The King’s Royal Rifles Corps 1st Bn. The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) 1st Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery (H.Q., A/E & B/O Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) 2nd Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery (H.Q., L/N & H/I Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) Divisional Troops st 1 Field Squadron, Royal Engineers (6) st 1 Field Park Troop, Royal Engineers (6) st 1 Armoured Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals (7) © www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 1 May 2019 [1 ARMOURED DIVISION (1939)] NOTES: 1. The 1st Armoured Division was a pre-war Regular Army formation, which was formerly known as The Mobile Division. It had been formed on 1 October 1937, being redesignated in late 1938. It originally comprised two light armoured brigades and a tank brigade, but in early 1939, it was agreed to reduce the establishment to one light and one heavy armoured brigade, although this did not take effect until November. -

Vol 68 No 2: March 2016

www.gurkhabde.com/publication The magazine for Gurkha Soldiers and their Families PARBATVol 68 No 2: MarchE 2016 In 2015 Kalaa Jyoti set up Arran House in North Kathmandu The sale of the orphans art will provide funding for 2016/17 art projects Through art we can enhance these orphans lives FRIDAY 22 APRIL 2PM TO SUNDAY 24 APRIL 4PM See films of the children’s art work as well as their ART paintings which EXHIBITION you can buy. KALAA JYOTI ART CHARITY THE GURKHA MUSEUM Kalaa Jyoti means “Art Enlightenment” in Nepali. We are raising PENINSULA BARRACKS money for this sustainable art project for orphan children in Nepal. ROMSEY ROAD The art fund will provide materials and training by Gordon WINCHESTER Davidson, the award winning internationally known Scottish artist. HAMPSHIRE SO23 8TS h www.thegurkhamuseum.co.uk 22 April 2016 2.00-4.30pm 23 & 24 April 10.00am – 4.30pm ii PARBATE Vol 68 No 2 March 2016 In 2015 Kalaa PARBATE In this edition we have a look at 10 Queen’s Jyoti set up Arran Own Gurkha Logistics Regiment receiving The Freedom of Rushmoor with a special House in North HQ Bde of Gurkhas, Robertson House, Sandhurst, Camberley, Surrey, GU15 4PQ. Parade in Aldershot on Sat 12 March. Kathmandu All enquiries Tel: 01276412614 More than 150 soldiers from the Regiment marched 94261 2614 through the town of Aldershot where they were cheered by the locals. (page 4). Fax: 0127641 2694 We also show you 1 RGR deployment in Mali on 94261 2694 Op NEWCOMBE. They are currently working with over The sale of the Email: [email protected] 20 nationals to provide basic infantry training to the Malian Armed Forces (page 20).