The Ormond Beach Mound, East Central Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outfall and Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Analysis 2015

INDIAN RIVER LAGOON OUTFALL AND SEA LEVEL RISE VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS 2015 Outfall and Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Analysis Prepared by: The East Central Florida Regional Planning Council April 2016 1 INDIAN RIVER LAGOON OUTFALL AND SEA LEVEL RISE VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS 2015 Page intentionally left blank 2 INDIAN RIVER LAGOON OUTFALL AND SEA LEVEL RISE VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS 2015 Table of Contents I. Introduction 4 II. Planning Process and Outreach 5 III. GIS Methodology 7 ECFRPC 7 UF GeoPlan 10 IV: County Inundation Analyses 12 Volusia County Vulnerability Analysis 13 Brevard County Vulnerability Analysis 15 Indian River Vulnerability Analysis 17 St. Lucie County Vulnerability Analysis 19 Martin County Vulnerability Analysis 21 Canal System Vulnerability Analysis 23 V: Study Area Inundation Maps 24 High Projection Rate Curve Maps 25 Intermediate Projection Rate Curve Maps 37 Low Projection Rate Curve Maps 49 VI: Maintenance Information 62 VII: Planning Team Contacts 66 VIII: Source Documentation 67 3 INDIAN RIVER LAGOON OUTFALL AND SEA LEVEL RISE VULNERABILITY ANALYSIS 2015 SECTION I: Introduction This vulnerability analysis is part of a grant awarded by the Florida Department of Economic Opportunity to the East Central Florida Regional Planning Council and the Treasure Coast Regional Planning Council to continue the work done for an associated grant awarded in 2014. As part of the 2014-15 planning project, the ECFRPC collected data and mapped all outfalls within the Indian River Lagoon, its connected water bodies and primary canals that flow into the lagoon system. As part of the 2014 project, the planning team also collected data for water quality, outfall ownership, and other important information. -

The Timucua Indians of Sixteenth Century Florida

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 18 Number 3 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 18, Article 4 Issue 3 1939 The Timucua Indians of Sixteenth Century Florida W. W. Ehrmann Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Ehrmann, W. W. (1939) "The Timucua Indians of Sixteenth Century Florida," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 18 : No. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol18/iss3/4 Ehrmann: The Timucua Indians of Sixteenth Century Florida THE TIMUCUA INDIANS OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY FLORIDA By W. W. EHRMANN The University of Florida (Bibliographical note. The most important sources on the Indians of northern Florida* at the time of the first European contacts are the writings of the Frenchmen Ribault and Laudon- niere, and the Franciscan monk Pareja who lived as a mis- sionary among them. A very graphic record of the life of the Timucua comes to us in the sketches of Le Moyne, who accom- panied Laudonniere. The best summaries of the original sources are those of Swanton and, to a less extent, Brinton. See full bibliography, post.) P HYSICAL E NVIRONMENT When first visited by the Spanish explorers in the early sixteenth century, northern Florida was inhabited by the Timucua family of Indians. -

Fiiiiiiiiliiiii

N • ffW ' ^fl 7 i I i r> Forn 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE-. i>~ (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Florida ^r COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Volusia INVtNIUKT - NUMINAIIUN hUKM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) -..y 7 19W fiiiiiiiiliiiii C OMMON: Tomoka State Park AND/OR HISTORIC: Nocoroco (.A--"^ v A- * - [flpilpij;^ STREET AND NUMBER: Two miles North of Ormond Beach on Old nivie* Highway CITY OR TOWN: J Ormond Beach Vicinity STATE CODE COUNTY: CODE Florida 17 Vnlns-ia 127 *st CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS ACCESSIBLE •z (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC C~] District (~~| Building SI Public Public Acquisition: Q Occupied Yes: o CXSite D Structure D Private Q In Process [X Unoccupied ^ Restricted D Object D Both D Being Considered r-, Preservation work D Unrcstricted in progress ' — ' u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) Z> 1 1 Agricultural I I Government Q3 Park ] | Transportation I I Comments &. | | Commercial 1 1 Industrial [~] Private Residence | | Other (Specify) H \ | Educational f~l Mi itary | | Reliqious I | Entertainment XH Museum | | Scientific ............. ^ OWNER'S NAME: u Division of Recreation & Parks. Dept^ of Nat-.nral R^poiirf •*. H IT UJ STREET AND NUMBER: ' ' *" ' ' 1 v • "~" O H UJ Larson Building CiTY OR TOWN: " STATE: CODE PJ Tallahassee Florida 12 iilllllliflil^ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: 0* COUNTY: Trustees of the Internal Improvement Fund H1 STREET AND NUMBER: ^ Elliott Building H- CITY OR TOWN: STATE CODE Tallahassee : Florida 1 ? |liiil:i|i|i||i|iiiiji:i:|illl TITUE OF SURVEY: ENTR Florida Archaeological Survey 4i '. -

July 2008 Inc

Volume XXXII • Issue 3 • July, 2008 4931 South Peninsula Drive • Ponce Inlet, Florida 32127 www.ponceinlet.org • www.poncelighthousestore.org (386) 761-1821 • [email protected] From the 2 Executive Director Events 3 Calendar Regional History 4 From Boom to Bust on the Halifax Feature Article Fishing 6 in Ponce Inlet Restoration & Preservation 9 Chance Bros. Lens Objects of the Quarter BB&T Bivalve 4th Order Lens Thank You & Wish List Volunteer 10 News Lighthouses of the World Torre de Hercules Light 120th 12 Anniversary Sponsors Gift Shop Features The Quarterly Newsletter of the Ponce de Leon Inlet LighthousePonce de Preservation Leon Inlet Light StationAssociation, • July 2008 Inc. From the Executive Director ood news! --After years of planning and hard door prizes for this special event. Please refer to our The Ponce de Leon Inlet Lighthouse Gwork by the Florida Lighthouse Association volunteer column on page 9 to learn more about this Preservation Association is dedicated to members, the Florida lighthouse license plate will special event and those honored for their dedicated the preservation and dissemination of be issued in early 2009. As the decrease in State service. the maritime and social history of the funding continues, and costs to maintain lighthouses The Association is proud to announce the recent Ponce de Leon Inlet Light Station. increase, this funding source is timely. Please consider acquisition of another Fresnel lens. Built in France by purchasing the “Visit Our Lights” license plate to help Barbier Benard and Turenne in the early 1900s, this 2008 Board of Trustees provide sustained funding for all Florida Lighthouses. -

EA IAA Cut DA-9 at Bakers Inlet

CESAD-ET-CO-M (CESAJ-C0/21Jun97) (ll-2-240a) 1st End Mr. DeVeaux/ dsm/(404) 331-6742 SUBJECT: Advanced Maintenance Dredging of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (IWW) Jacksonville to Miami, in the Vicinity of Bakers Haulover Inlet, Dade County, Florida Commander, South Atlantic Division, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 77 Forsyth Street, S.W., Room 322, Atlanta, Georgia 30303-3490 10 July 1997 FOR THE COMMANDER, JACKSONVILLE DISTRICT, ATTN: CESAJ-CO 1. Your request to perform advanced maintenance in subject channel is approved subject to completing all appropriate environmental documentation, coordination, and clearance. Approval of the Memorandum of Agreement with the Florida Inland Navigation District is also required. 2. You should continue to monitor the cost of maintenance to assure that the proposed advanced maintenance dredging results in the least costly method of maintaining the channel. FOR THE DIRECTOR OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNICAL SERVICES: ~&Peei JR., PE~ . Chief, Construction-Operations ~ Directorate of Engineering and Technical Services !<. c v ~...': 7 Yv / 9 7 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY JACKSONVILLE DISTRICT CORPS OF ENGINEERS P. 0. BOX 4970 JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA 32232-0019 REPLY TO ATTENTION OF CESAJ-CO (ll-2-240a) 21 June 1997 ~MORANDUM FOR CDR, USAED (CESAD-ET-CO-M), ATLANTA, GA 30335 SUBJECT: Advanced Maintenance Dredging of the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway (IWW) Jacksonville to Miami, in the Vicinity of Bakers Haulover Inlet, Dade County, Florida 1. Reference ER 1130-2-520. 2. Advanced maintenance dredging is proposed for the IWW in the vicinity of Bakers Haulover Inlet to reduce the frequency of dredging required for this reach of the IWW. -

Outstanding Bridges of Florida*

2013 OOUUTTSSTTAANNDDIINNGG BBRRIIDDGGEESS OOFF FFLLOORRIIDDAA** This photograph collection was compiled by Steven Plotkin, P.E. RReeccoorrdd HHoollddeerrss UUnniiqquuee EExxaammpplleess SSuuppeerriioorr AAeesstthheettiiccss * All bridges in this collection are on the State Highway System or on public roads Record Holders Longest Total Length: Seven Mile Bridge, Florida Keys Second Longest Total Length: Sunshine Skyway Bridge, Lower Tampa Bay Third Longest Total Length: Bryant Patton Bridge, Saint George Island Most Single Bridge Lane Miles: Sunshine Skyway Bridge, Lower Tampa Bay Most Dual Bridge Lane Miles: Henry H. Buckman Bridge, South Jacksonville Longest Viaduct (Bridge over Land): Lee Roy Selmon Crosstown Expressway, Tampa Longest Span: Napoleon Bonaparte Broward Bridge at Dames Point, North Jacksonville Second Longest Span: Sunshine Skyway Bridge, Lower Tampa Bay Longest Girder/Beam Span: St. Elmo W. Acosta Bridge, Jacksonville Longest Cast-In-Place Concrete Segmental Box Girder Span: St. Elmo W. Acosta Bridge, Jacksonville Longest Precast Concrete Segmental Box Girder Span and Largest Precast Concrete Segment: Hathaway Bridge, Panama City Longest Concrete I Girder Span: US-27 at the Caloosahatchee River, Moore Haven Longest Steel Box Girder Span: Regency Bypass Flyover on Arlington Expressway, Jacksonville Longest Steel I Girder Span: New River Bridge, Ft. Lauderdale Longest Moveable Vertical Lift Span: John T. Alsop, Jr. Bridge (Main Street), Jacksonville Longest Movable Bascule Span: 2nd Avenue, Miami SEVEN MILE BRIDGE (new bridge on left and original remaining bridge on right) RECORD: Longest Total Bridge Length (6.79 miles) LOCATION: US-1 from Knights Key to Little Duck Key, Florida Keys SUNSHINE SKYWAY BRIDGE RECORDS: Second Longest Span (1,200 feet), Second Longest Total Bridge Length (4.14 miles), Most Single Bridge Lane Miles (20.7 miles) LOCATION: I–275 over Lower Tampa Bay from St. -

3.0 Precontact Review

3-1 3.0 PRECONTACT REVIEW A discussion of the regional prehistory is included in cultural resource reports in order to provide a framework within which to examine the local archaeological record. Archaeological sites are not individual entities, but were once part of a dynamic cultural system. As a result, individual sites cannot be adequately examined or interpreted without reference to other sites and resources in the general area. In general, archaeologists summarize the prehistory of a given area (i.e., the archaeological region) by outlining the sequence of archaeological cultures through time. Archaeological cultures are defined largely in geographical terms, but also reflect shared environmental and cultural traits. The Wekiva Parkway/SR 46 Realignment PD&E Study area is situated within the East and Central Lake archaeological region, as defined by Milanich and Fairbanks (1980) and Milanich (1994) (Figure 3.1). The spatial boundaries of the region are somewhat arbitrary, and it is after 500 B.C. that characteristic regional differences become more evident in the archaeological record. There are differences, however, evident as early as the Middle Archaic period when the characteristic Mount Taylor horizon develops along the St. Johns River. The Paleo-Indian, Archaic, Formative, Mississippian, and Acculturative stages have been defined based on unique sets of material culture traits such as characteristic stone tool forms and ceramics, as well as subsistence, settlement, and burial patterns. These broad temporal units are further subdivided into culture horizons, phases or periods: Paleo- Indian (Clovis, Suwannee, Dalton?), Early Archaic (Bolen, Kirk), Mount Taylor, Orange, St. Johns I, St. Johns Ia, St. -

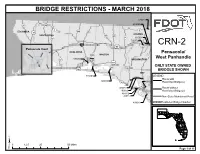

Bridge Restrictions

BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2018 <Double-click here to enter title> 520031 610002 «¬97 «¬89 4 2 ESCAMBIA «¬ 189 29 «¬ 85 «¬ ¤£ «¬ HOLMES SANTA ROSA 187 83 «¬ «¬ 81 610001 87 «¬ «¬ 520076 10 ¬ CRN-2 ¨¦§ 90 79 Pensacola Inset ¤£ «¬ OKALOOSA Pensacola/ «¬285 WALTON «¬77 570055 West Panhandle «¬87 ¦¨§293 WASHINGTON ¤£331 ONLY STATE OWNED «¬83 20 ¤£98 «¬ BRIDGES SHOWN BAY 570091 LEGEND Route with 600108 «¬30 460020 Restricted Bridge(s) 460051 368 Route without 460052 «¬ Restricted Bridge(s) 460112 460113 Non-State Maintained Road 460019 ######Restricted Bridge Number 0 12.5 25 50 Miles ¥ Page 1 of 16 BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2018 610001 610002 <Double-click here to enter title> 520031 «¬2 HOLMES «¬75 JACKSON 530005 520076 530173 ¬79 CRN-2 « 610004 500092 550144 540042 Central Panhandle ¬77 GADSDEN 27 « ¦¨§10 ¤£ WASHINGTON JEFFERSON 460051 19 460052 470029 ¤£ ONLY STATE OWNED 65 BAY «¬ BRIDGES SHOWN CALHOUN «¬71 ¬267 388 « 231 73 59 LEGEND «¬ ¤£ «¬ LEON «¬ Route with Tallahassee Inset 540069 Restricted Bridge(s) 460020 LIBERTY 368 «¬ Route without 22 WAKULLA «¬ 590014 Restricted Bridge(s) 61 «¬ 30 460112 «¬ Non-State Maintained Road 460113 375 460019 GULF «¬ 540032 T ###### Restricted Bridge Number 380049 490018 «¬377 ¤£98 FRANKLIN «¬30 ¤£319 «¬300 0 12.5 25 50 Miles ¥ Page 2 of 16 BRIDGE RESTRICTIONS - MARCH 2018 350030 <Double-click320017 here to enter title> JEFFERSON «¬145 540042 41 19 ¤£ ¤£ 55 2 «¬ ¬47 «¬ 53 6 HAMILTON «COLUMBIA «¬ «¬ 720026 10 ¦¨§ 290030 59 370015 «¬ 350044 540069 MADISON ¤£441 BAKER 370013 290071 CRN-2 370014 270067 -

By 1890, Florida's Population Is 390000

Panel 1.4 1889 view of Jupiter Lighthouse from the railroad dock Waves of people board trains and move to what recently was a mostly empty state; by 1890, Florida’s population is 390,000 (doubling in two decades). Freed African-Americans make up half the state’s population in this post-Civil War era. e roseate spoonbill and reddish egret are nearly gone from the Everglades, decimated by the plumage demand for fashionable hats of the day. Entrepreneurs conduct large-scale draining to connect waterways, permanently altering the hydrology of South Florida. By 1883, the Caloosahatchee River is connected to Lake Okeechobee, lowering the lake’s water level and reducing water flow to the Everglades. 1881 Hamilton Disston buys 4 million acres of the Everglades. The cost is 25 cents an acre. In the aftermath of the Civil War, the state’s nearly bankrupt Internal Improvement Fund — recovering from the severe disruption of its infant railroad system — is seeking buyers for land. Disston, a wealthy saw Hamilton Disston connects waterways to Lake Okeechobee works owner from Philadelphia, returns the Fund to solvency in Central Florida, and by the fall of 1883 watercraft traverse with this single transaction. from the town of Kissimmee to the Gulf of Mexico 1883 Disston connects the Caloosahatchee River and Upper Chain of Lakes. Proclaiming he will drain the entire Everglades, Disston begins by dredging canals and connecting lakes Kissimmee, Hatchineha, Tohopekaliga and other lakes that form the headwaters for the Kissimmee River. He begins to deepen and straighten the Kissimmee River, selling the surrounding drained lands to cattle operators for grazing. -

Tomoka State Park Tomoka of the Park Forming a Natural Peninsula

Florida State Parks History & Nature Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks The Tomoka River and the Halifax River (the Intracoastal Waterway) meet at the north end Tomoka State Park Tomoka of the park forming a natural peninsula. With 2099 North Beach Street 12 miles of shoreline, the park’s 2,000 plus acres Ormond Beach, FL 32174 Central State Park (386) 676-4050 covers maritime hammock and estuarine Florida salt marshes. FloridaStateParks.org In the early 1600s, Spanish explorers found The largest stand of old growth live oak in Indians living here in a village called Nocoroco. Park Guidelines Eastern Florida Although nothing remains of the village, shell • Hours are 8 a.m. until sunset, 365 days a year. middens—mounds of oyster and snail shells from • An entrance fee is required. decades of Native American meals—reach 40 feet • All plants, animals and park property are high at the river bank. protected. Collection, destruction or disturbance is prohibited. Tomoka State Park is noted for its live oak • Pets are permitted in designated areas only. Pets hammock with arching limbs covered in Spanish must be kept on a leash no longer than 6 feet moss, resurrection fern and green-fly orchids. and well behaved at all times. Indian pipe, spring coralroot and Florida coontie • Fishing, boating, swimming and fires are allowed grow under the hammock canopy, while wild in designated areas only. A Florida fishing license coffee and tropical sage can be found on the shell may be required. middens. Visitors may explore the green world of • Fireworks and hunting are prohibited in all Florida this hammock on the half-mile nature trail. -

Port Orange Shoreline Habitat Management Plan

CITY COUNCIL AGENDA FORM REQUESTED COUNCIL MEETING DATE: 07/21/09 SUBJECT: SHORELINE HABITAT RESTORATION & MANAGEMENT PLAN DEPARTMENT: CITY MANAGER/COMMUNITY REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY RECOMMENDED MOTION: To accept the Shoreline Habitat Restoration & Management Plan, as presented. SUMMARY: The City of Port Orange is one of several coastal communities within the boundaries of the St. Johns River Water Management District’s Northern Coastal Basin program. The City participates in an inter-agency group formed by the District in June 2007, with the goal of developing and demonstrating best management practices for shoreline development and restoration. Under the leadership of Paul Haydt, the District has completed a comprehensive survey of the shoreline in Port Orange, and has identified six (6) areas for pilot restoration projects. To compliment and further the District’s efforts, the City employed Denis Frazel, Frazel, Inc., to develop a comprehensive Shoreline Habitat and Restoration Management Plan for the City. This Plan includes the District’s recommended shoreline restoration projects, as well as best management practices to guide the City as it develops and redevelops along its shoreline. Modifications to the City’s Comprehensive Plan and Land Development Regulations are also recommended to support shoreline habitat restoration and management, and to ensure that required mitigation for shoreline impacts are undertaken within the community. Mr. Frazel will be presenting the final draft of his plan to the City Council. ATTACHMENTS: Ordinance Resolution Budget Resolution Other Support Documents/Contracts DEPARTMENT Submitted by Date CITY MANAGER Approved Agenda Item For: COUNCIL ACTION: [ ] Approved as Recommended [ ] Disapproved [ ] Tabled Indefinitely [ ] Continued to Date Certain [ ] Approved with Modification Shoreline Habitat Restoration & Management Plan July 2009 City of Port Orange Shoreline Habitat Restoration and Management Plan Prepared by: Denis W. -

Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program Report for the State of Florida

Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program report for the State of Florida Item Type monograph Publisher Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Download date 09/10/2021 18:01:24 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/41152 ISSN 1930-1448 Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program Report for the State of Florida KARA R. RADABAUGH, STEPHEN P. GEIGER, RYAN P. MOYER, EDITORS Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Technical Report No. 22 • 2019 MyFWC.com Oyster Integrated Mapping and Monitoring Program Report for the State of Florida KARA R. RADABAUGH, STEPHEN P. GEIGER, RYAN P. MOYER, EDITORS Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish and Wildlife Research Institute 100 Eighth Avenue Southeast St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 MyFWC.com Technical Report 22 • 2019 Ron DeSantis Governor of Florida Eric Sutton Executive Director Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission The Fish and Wildlife Research Institute is a division of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which “[manages] fish and wildlife resources for their long-term well-being and the benefit of people.” The Institute conducts applied research pertinent to managing fishery resources and species of special concern in Florida. Pro- grams focus on obtaining the data and information that managers of fish, wildlife, and ecosystems need to sustain Florida’s natural resources. Topics include managing recreationally and commercially important fish and wildlife species; preserving, managing, and restoring terrestrial, freshwater, and marine habitats; collecting information related to population status, habitat requirements, life history, and recovery needs of upland and aquatic species; synthesizing ecological, habitat, and socioeconomic information; and developing educational and outreach programs for classroom educators, civic organizations, and the public.