Hart, Rushmoor and Surrey Heath SHMA Published in December 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Housing Market Partnership for Hart District Council, Rushmoor Borough

Housing Market Partnership for the administrative areas of Hart, Rushmoor and Surrey Heath Terms of Reference (Version 3) Purpose 1. To ensure the Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessments are robust and credible in that they will deliver the core outputs and follow the process checklist as appended 2. To receive and consider reports from commissioned consultants (where appropriate) and feedback from the wider stakeholder group 3. To share and pool information and intelligence, including relevant contextual intelligence and policy information on housing land availability, housing market and financial data 4. To support core members in the analysis and interpretation of the assessment data 5. To consider the implications of the assessments, including signing off the assessment reports, core outputs and agreeing follow up action 6. To agree a process by which the SHLAA findings can be regularly reviewed Membership At its outset, the membership will comprise representatives from the following bodies: Hart District Council Rushmoor Borough Council Surrey Heath Borough Council Berkeley Homes Barton Willmore Mitchell and Partners Gregory Gray Associates Annington Property Ltd Barratt Southern Counties Mitchell and Partners Re-Format Architects Sentinel HA Accent Peerless First Wessex Housing Lovell Partnerships The Rund Partnership Rippon Development Services MGA Planning Rio Homes and Estates These are the organisations that attended either the first meeting, the second meeting, or both. Other key stakeholders1 can join the partnership should they wish to do so by contacting either Hart District Council, Rushmoor Borough Council, or Surrey Heath Borough Council. New members will be invited as necessary to ensure that the housing market area is represented with at least one house builder and preferably with other key stakeholders such as local property and planning agents, Registered Social Landlords and key landowners. -

LDF Thank You for the Opportunity to Comment. Surrey Heath Have No

LDF From: Jane Ireland <[email protected]> Sent: 13 April 2015 16:41 To: LDF Subject: RE: Publication of the Reigate & Banstead Community Infrastructure Levy Draft Charging Schedule Thank you for the opportunity to comment. Surrey Heath have no comments on the CIL charging schedule. Regards Jane Ireland Planning Policy and Support Manager Policy and Conservation Surrey Heath Borough Council Knoll Road Camberley GU15 3HD (01276 707213) www.surreyheath.gov.uk Great Place l Great Community l Great Future From: LDF [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: 13 April 2015 12:09 To: LDF Subject: Publication of the Reigate & Banstead Community Infrastructure Levy Draft Charging Schedule Dear Sir/Madam In accordance with Regulation 16 of the Community Infrastructure Levy Regulations 2010 (as amended), I am writing to inform you of publication of the Reigate and Banstead Infrastructure Levy (CIL) Draft Charging Schedule, and invite your comments on the document. A copy of the CIL Draft Charging Schedule and Statement of Representations Procedure are attached to this email. These documents are also available to view on the Council’s website at www.reigate- banstead.gov.uk/cil, along with a range of relevant evidence and supporting documentation. Documents are also available for inspection at the Town Hall in Reigate and hard copies of all documents are available on request from 01737 276178 or [email protected]. You are encouraged to respond using the standard response form which is also available to download or on request using the details above. Responses must be submitted to the Council by 5pm, Tuesday 26 May 2015: By email to: [email protected]; or By post to: Planning Policy Team, Reigate & Banstead Borough Council, Town Hall, Castlefield Road, Reigate, Surrey, RH2 0SH. -

Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery Phase 1 GDPR Privacy Notice

Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery Phase 1 GDPR Privacy Notice Privacy Notice This notice sets out how Woking Borough Council as the lead authority on behalf of the consortium of the following local authorities Elmbridge Borough Council, Epsom & Ewell Borough Council, Guildford Borough Council, Mole Valley District Council, Reigate & Banstead Borough Council, Spelthorne Borough Council, Surrey Heath Borough Council, Tandridge District Council Waverley Borough Council, Woking Borough Council and Surrey County Council will use your personal data, and your rights. It is made under Articles 13 and/or 14 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This notice relates to data collected under the Green Jump Surrey scheme operated by Woking Borough Council and Action Surrey, which is funded by the Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery Scheme (GHG LAD) run by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. Action Surrey is an energy efficiency advice service established by Surrey local authorities and operated by ThamesWey Sustainable Communities, a company wholly owned by Woking Borough Council. YOUR DATA The data We will process the following personal data: Customers: - Address and details of property receiving the GHG LAD installation(s) - Details about the GHG LAD installation(s) installed at the property, including type, size and cost - Contact address (if not the property receiving the GHG LAD installation(s)) - Address and details of property offered, but not receiving, the GHG LAD installation(s) - Your -

Volunteer Opportunities Across Surrey

VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES ACROSS SURREY: Age Concern Epsom and Ewell Visiting and Befriending service covering the following areas: KT4, KT6, KT9 KT17 – KT22 SM2 – SM3 Volunteer drivers also required Please contact Liz Hope, Volunteer Co-coordinator Call: 01372 732458 Email: [email protected] Surrey Heath Age Concern Visiting and Befriending service in the following areas: GU15 – GU20 Volunteers drivers also required Please contact Gill Gibson, Charity Manager Call: 01276 707585 Email: [email protected] Age Concern Merstham, Redhill and Reigate Visiting and Befriending service in the following areas: RH1 – RH2, RH6 Volunteer opportunities across Surrey 10/17 Volunteer drivers also required Please contact Sandy Featherstonhaugh, Business Manager Call: 01737 645636 Email: [email protected] Age Concern Banstead Visiting and Befriending service in the following areas: SM2 Call: 01737 352156 Email: [email protected] Age Concern Mole Valley Visiting and Befriending service in the following areas: RH4 – RH5 KT21 – KT23 Please contact: Julia Gallagher, Volunteer Co-ordinator Call: 01306 899104 or 07442 017169 Email: [email protected] Age Concern Woking Visiting and Befriending service in the following areas: GU21 – GU24 Call: 01483 770753 Email: [email protected] Volunteer opportunities across Surrey 10/17 Visiting Friends Visiting and Befriending service and Day Care Service in the following areas: GU21 – GU24 KT12 – KT14 Please contact: Sandra Smook, Manager Call: -

Surrey Strategic Partnership Plan 2010 - 2020

Standing up for Surrey Surrey Strategic Partnership Plan 2010 - 2020 This document is available from www.surreycc.gov.uk/communityplanning If you would like more information on the Surrey Strategic Partnership to comment on the Community Strategy to know how you can get involved or contribute to some of the work described in this document Please contact us: Tel: 020 8541 7406 email: [email protected] If you would like this document in large print, on tape or in another language please contact us on: Tel: 03456 009 009 Fax: 020 8541 9004, Minicom: 020 8541 8914 email: [email protected] The Surrey Strategic Partnership produced this plan on behalf of Surrey’s public sector agencies, business, voluntary, community, and faith sectors. This plan fulfils the requirements of the Local Government Act 2000, which requires Surrey County Council to prepare a Sustainable Community Strategy with partners that demonstrates how local organisations and agencies will work together to improve the economic, social and environmental well-being of the county. Contents Contents Foreword by Dr Andrew Povey ................................................................................... 4 Part 1.............................................................................................................................. 6 Surrey in 2020 ............................................................................................................... 8 Five Key Challenges.................................................................................................... -

Spelthorne Borough Council, Council Offices, Knowle Green, Staines-Upon-Thames, TW18 1XB

Richard Allen Contact: Ann Biggs Planning Inspectorate Department: Regeneration & Growth (via email) Service: Strategic Planning Direct line: 01784 448619 Email [email protected] Date: 23 September 2019 Dear Richard Southampton to London Pipeline Rule 6 Letter – Response to Draft Examination Timetable We are in receipt of the Rule 6 letter in respect of the Southampton to London Pipeline (SLP) scheme accepted by the Planning Inspectorate under the Development Consent Order regime. As a host authority for the route, Spelthorne Borough Council has confirmed its attendance at the Preliminary Meeting to be held on 9 October 2019. We wish to give advance notice to the Examining Authority that we will be raising the following matter at meeting. It appears from the Draft Examination Timetable that the hearings are proposed to be topic-based, covering issues along the length of the route. It is the view of Spelthorne and the other host authorities in Surrey (Runnymede Borough Council, Surrey Heath Borough Council and Surrey County Council) that it would be more practical and productive if the hearings were organised geographically, so that each hearing covered a section of the route with all relevant issues relating to a given section being heard on that day. This would allow for matters to be discussed at greater depth and would be more practical for attendees and participants. We also suggest that the hearings themselves be conducted at a location close to the section of the route being heard on that day and Runnymede BC have offered its council chamber as a potential venue for a hearing covering the northern section of the route. -

Habitats Regulations Assessment

South Oxfordshire Local Plan 2034 Final Publication Version 2nd Habitats Regulations Assessment Prepared by LUC in association Air Quality Assessments Ltd December 2018 Project Title: Habitats Regulations Assessment for South Oxfordshire Local Plan Client: South Oxfordshire District Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by 1.0 04/12/18 Draft for client comment Sarah Smith Jeremy Owen Jeremy Owen Natalie Collins Rebecca Turner David Green 2.0 20/12/18 Final for publication Sarah Smith David Green Jeremy Owen David Green Jeremy Owen South Oxfordshire HRA Update Stage 2 Appropriate Assessment Last saved: 20/12/2018 09:18 South Oxfordshire Local Plan 2034 Final Publication Version 2nd Habitats Regulations Assessment Prepared by LUC in association Air Quality Assessments Ltd December 2018 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street Bristol Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Edinburgh Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Glasgow 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Lancaster London NW1 1JD GIS & Visualisation [email protected] Manchester FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Executive Summary Introduction This document presents the methodology and findings of the Habitats Regulations Assessment of the South Oxfordshire Local Plan 2034 Final Publication Version 2nd (due to be published in January 2019), which is being produced by South Oxfordshire District Council. Once adopted, the Local Plan will set out policies and guidance for development in the District over the next 15 years to 2034. Development plans, such as the South Oxfordshire Local Plan, are subject to a process called Habitats Regulations Assessment (HRA). -

We Have Provided Political and Community

We have provided political and community engagement support to clients in the following local authority areas: London East London Borough of Bexley Babergh District Council London Borough of Bromley Basildon Council London Borough of Croydon Bedford Borough Council London Borough of Ealing Braintree District Council London Borough of Enfield Brentwood Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Central Bedfordshire Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham Chelmsford City Council London Borough of Havering Colchester Borough Council London Borough of Hounslow Dacorum Borough Council London Borough of Lambeth East Herts District Council London Borough of Lewisham Epping Forest District Council London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Hertsmere Borough Council London Borough of Southwark Huntingdonshire District Council London Borough of Sutton Ipswich Borough Council London Borough of Wandsworth Maldon District Council Royal Borough of Greenwich North Hertfordshire District Council Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea South Cambridgeshire District Council Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames South Norfolk Council Westminster City Council St Albans City & District Council Stevenage Borough Council South East Tendring District Council Arun District Council Uttlesford District Council Aylesbury Vale District Council Welwyn Hatfield Borough Council Brighton & Hove City Council Buckinghamshire County Council Midlands Canterbury City Council Daventry District Council Cherwell District Council Derbyshire Dales District Council Chichester -

Statement of Common Ground

V1.0 SCG 6 Statement of Common Ground Housing need and delivery across the Hart/Rushmoor/Surrey Heath housing market area Agreed between Hart District Council, Rushmoor Borough Council and Surrey Heath Borough Council 1/11/18 1 V1.0 1 Introduction 1.1. This Statement of Common Ground (SOCG) has been prepared jointly between Hart District Council (“Hart” or “the Council”) Rushmoor Borough Council (“Rushmoor”) and Surrey Heath Borough Council (“Surrey Heath”). It sets out the agreed position between the three authorities, which together comprise the housing market area (HMA), on the matter of addressing housing need across the HMA. 2. Background 2.1. The three authorities have a long-standing track record of joint working on plan making related matters including meaningful engagement over housing allocation and delivery. A North East Hampshire and North West Surrey strategic housing market sub-region had been identified in accordance with then Practice Guidance (2007) and the first SHMA was published in 2009 by the three authorities.1 2.2. This first SHMA was reviewed in 2014 including confirmation of the housing market area as based on published census information including migration and travel to work patterns. A second SHMA was jointly published in December 20142 2.3. The most recent joint SHMA3 is a 2016 update of the 2014 SHMA to include more recent data from ONS/DCLG (2012-base plus MYE for 2014 and 2014 with 53% uplift for market signals, affordability and employment trends). This current SHMA refers to the period 2014-2032. 2.4. At the time of that publication, although the Local Plans Expert Group had reported recommending the reform of housing need assessments the Government had not, at that point, indicated preference for this. -

Mole Valley Social Care, Community Support and Health Contacts

Mole Valley Social Care, Community Support and Health Contacts Mole Valley Locality Team Adult Social Care Mole Valley District Council, Pippbrook, Mole Valley District Council Reigate Road, Dorking , RH4 1SJ Pippbrook, Reigate Road, Tel: 01372 833456 Email: Dorking, RH4 1SJ [email protected] Tel: 01306 885001 SMS: 07771 576411 Out of Hours: 01372 376533 Epsom General Hospital Email: [email protected] Adult Social Care Team Rowan House, Epsom General Hospital, Customer Support Services – Dorking Road, Epsom, KT18 7EG Day and Wellbeing centres and Telecare Tel: 01372 735297 Fax: 01372 735256 Tel: 01372 376058 Mental Health Services Telecare: Tel: 0137 204500 SMS: 0800 00385 Older People Team Email: [email protected] Tel: 0300 222 5716 Learning Disabilities Team Dial-A-Ride (Mole Valley) Tel: 01372 202100 Tel: 01372 38333 18 – 64 Team Email: [email protected] Tel: 01306 502400 SMS: 07717 989024 Age UK Surrey (countywide service) Rex House, William Road, Guildford, GU1 4QZ Learning Disability Acute Liaison Service Tel: 01483 503414 Epsom General Hospital Email: [email protected] Tel: 07920 561343 www.ageuk.org.uk/surrey/ Learning Disability Primary Care Age Concern Mole Valley Liaison Nurse The Point, Mayflower, Lyons Court, Dorking RH4 Surrey Downs Clinical Commissioning Group 1AB Contact: Hollie Roberts Tel: 07799 581566 Tel: 01306 899104 or 07442 017169 Email: [email protected] Safe Haven (Epsom) The Larches, 44 Waterloo Road Community Connections – Epsom, KT19 8EX Mary Frances Trust Tel: 0300 55 55 222 For support with mental health. Citizens Advice (Dorking) 23 The Crescent, Leatherhead, Lyons Court, High Street, Dorking RH4 1AB Surrey, KT22 8DY Tel: 03444 111 444 Tel: 01372 375400 SMS: 07929 024722 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.maryfrancestrust.org.uk Safeguarding Advisor (Mid Surrey Area) Contact: Nicola Davies Tel: 07805 688046 Mole Valley Wellbeing Centre Email: [email protected] Local support for people with dementia and carers. -

Pharmacy Name

Pharmacy Name ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 COUNTY POSTCODE CCG area Abbott's Pharmacy 83 High Street Lindfield West Sussex RH16 2HN Horsham & Mid Sussex Anachem Pharmacy 210 Chessington Road West Ewell Surrey KT19 9XA Surrey Downs Arlington Road Medical Arlington Road Pharmacy Practice 1 Arlington Road Eastbourne East Sussex BN21 1DH Eastbourne, Hailsham & Seaford Arun Valley Pharmacy 38 Station Road Billingshurst West Sussex RH14 9SE Coastal West Sussex Crowhurst Road Off Carden Asda Store Pharmacy Avenue, Hollingbury Brighton BN1 8AS Brighton & Hove Asda Store Pharmacy The Marina Brighton BN2 5UT Brighton & Hove Asda Store Pharmacy Littlehampton Road Ferring Worthing West Sussex BN12 6PN Coastal West Sussex Asda Store Pharmacy Pegler Way Crawley West Sussex RH11 7AH Crawley Pevensey Bay Asda Store Pharmacy Crumbles Harbour Village Road Eastbourne East Sussex BN23 6JH Eastbourne, Hailsham & Seaford St Leonards on Asda Store Pharmacy Battle Road Sea East Sussex TN37 7AA Hastings & Rother Asda Store Pharmacy Reigate Road Burgh Heath Surrey KT20 5NZ Surrey Downs Highgate Works, Ashdown Pharmacy The Rookery Studio Tomtits Lane Forest Row East Sussex RH18 5AT High Weald, Lewes & Havens Ashford Lodge Pharmacy 122 Feltham Hill Road Ashford Surrey TW15 2BX North West Surrey Ashington Pharmacy Unit 1 Clearview House London Road Ashington West Sussex RH20 3DD Coastal West Sussex Ashtons Hospital Pharmacy Services Ltd Unit 4 Dyke Road Mews 74-76 Dyke Road Brighton East Sussex BN1 3JD Brighton & Hove Ashtons Late Night Pharmacy 98 Dyke Road Brighton -

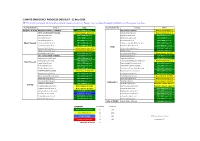

Progress Summary 250520

CLIMATE EMERGENCY PROGRESS CHECKLIST - 25 May 2020 NB. This is work in progress! We have almost certainly missed some actions. Please contact [email protected] with any news or updates. County/Authority Council Status County/Authority Council Status Brighton & Hove BRIGHTON & HOVE CITY COUNCIL DECLARED Dec 2018 KENT COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed May 2019 WEST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL Motion Passed - April 2019 Ashford Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 Adur Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Canterbury City Council DECLARED July 2019 Arun District Council DECLARED Nov 2019 Dartford Borough Council DECLARED Oct 2019 Chichester City Council DECLARED June 2019 Dover District Council DECLARED Jan 2020 West Sussex Chichester District Council DECLARED July 2019 Folkestone and Hythe District Council DECLARED July 2019 Crawley Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Gravesham Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Kent Horsham District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Maidstone Borough Council DECLARED April 2019 Mid Sussex District Council Motion Passed - June 2019 Medway Council DECLARED April 2019 Worthing Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Sevenoaks District Council Motion Passed - Nov 2019 EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL DECLARED Oct 2019 Swale Borough Council DECLARED June 2019 Eastbourne Borough Council DECLARED July 2019 Thanet District Council DECLARED July 2019 Hastings Borough Council DECLARED Dec 2018 Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Motion Passed July 2019 East Sussex Lewes District Council DECLARED July 2019 Tunbridge Wells