Current Status of the IAU MDC Meteor Showers Database

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP

SIERRA COLLEGE OBSERVATIONAL ASTRONOMY LABORATORY EXERCISE Lab N03: Celestial Navigation (Fall) NAME GROUP OBJECTIVE: Learn about the Celestial Coordinate System. Learn about stellar designations. Learn about deep sky object designations. INTRODUCTION: The Horizon Coordinate System is simple, but flawed, because the altitude and azimuth measures of stars change as the sky rotates. Astronomers have developed an improved scheme called the Celestial Coordinate System, which is fixed with the stars. The two coordinates are Right Ascension and Declination. Declination ranges from the North Celestial Pole to the South Celestial Pole, with the Celestial Equator being a line around the sky at the midline of those two extremes. We will use these coordinates when navigating using the SC001 and SC002 charts. There are many ways to designate stars. The most common is called the Bayer designations. The Bayer designation of a star starts with a Greek letter. The brightest star in the constellation gets “alpha” (the first letter in the Greek alphabet), the second brightest star gets “beta,” and so on. (The Greek alphabet is shown below.) The Bayer designation must also include the constellation name. There are only 24 letters in the Greek alphabet, so this system is obviously very limited. The Greek alphabet 1) Alpha 7) Eta 13) Nu 19) Tau 2) Beta 8) Theta 14) Xi 20) Upsilon 3) Gamma 9) Iota 15) Omicron 21) Phi 4) Delta 10) Kappa 16) Pi 22) Chi 5) Epsilon 11) Lambda 17) Rho 23) Psi 6) Zeta 12) Mu 18) Sigma 24) Omega A more extensive naming system is called the Flamsteed designation. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

A&A 598, A40 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201629659 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics Separation and confirmation of showers? L. Neslušan1 and M. Hajduková, Jr.2 1 Astronomical Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, 05960 Tatranska Lomnica, Slovak Republic e-mail: [email protected] 2 Astronomical Institute, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dubravska cesta 9, 84504 Bratislava, Slovak Republic e-mail: [email protected] Received 6 September 2016 / Accepted 30 October 2016 ABSTRACT Aims. Using IAU MDC photographic, IAU MDC CAMS video, SonotaCo video, and EDMOND video databases, we aim to separate all provable annual meteor showers from each of these databases. We intend to reveal the problems inherent in this procedure and answer the question whether the databases are complete and the methods of separation used are reliable. We aim to evaluate the statistical significance of each separated shower. In this respect, we intend to give a list of reliably separated showers rather than a list of the maximum possible number of showers. Methods. To separate the showers, we simultaneously used two methods. The use of two methods enables us to compare their results, and this can indicate the reliability of the methods. To evaluate the statistical significance, we suggest a new method based on the ideas of the break-point method. Results. We give a compilation of the showers from all four databases using both methods. Using the first (second) method, we separated 107 (133) showers, which are in at least one of the databases used. These relatively low numbers are a consequence of discarding any candidate shower with a poor statistical significance. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Observing Exoplanets

Observing Exoplanets Olivier Guyon University of Arizona Astrobiology Center, National Institutes for Natural Sciences (NINS) Subaru Telescope, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, National Institutes for Natural Sciences (NINS) Nov 29, 2017 My Background Astronomer / Optical scientist at University of Arizona and Subaru Telescope (National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Telescope located in Hawaii) I develop instrumentation to find and study exoplanet, for ground-based telescopes and space missions My interest is focused on habitable planets and search for life outside our solar system At Subaru Telescope, I lead the Subaru Coronagraphic Extreme Adaptive Optics (SCExAO) instrument. 2 ALL known Planets until 1989 Approximately 10% of stars have a potentially habitable planet 200 billion stars in our galaxy → approximately 20 billion habitable planets Imagine 200 explorers, each spending 20s on each habitable planet, 24hr a day, 7 days a week. It would take >60yr to explore all habitable planets in our galaxy alone. x 100,000,000,000 galaxies in the observable universe Habitable planets Potentially habitable planet : – Planet mass sufficiently large to retain atmosphere, but sufficiently low to avoid becoming gaseous giant – Planet distance to star allows surface temperature suitable for liquid water (habitable zone) Habitable zone = zone within which Earth-like planet could harbor life Location of habitable zone is function of star luminosity L. For constant stellar flux, distance to star scales as L1/2 Examples: Sun → habitable zone is at ~1 AU Rigel (B type star) Proxima Centauri (M type star) Habitable planets Potentially habitable planet : – Planet mass sufficiently large to retain atmosphere, but sufficiently low to avoid becoming gaseous giant – Planet distance to star allows surface temperature suitable for liquid water (habitable zone) Habitable zone = zone within which Earth-like planet could harbor life Location of habitable zone is function of star luminosity L. -

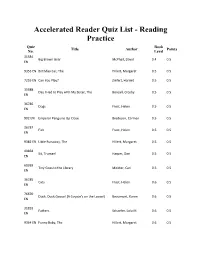

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 31584 Big Brown Bear McPhail, David 0.4 0.5 EN 9353 EN Birthday Car, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 7255 EN Can You Play? Ziefert, Harriet 0.5 0.5 35988 Day I Had to Play with My Sister, The Bonsall, Crosby 0.5 0.5 EN 36786 Dogs Frost, Helen 0.5 0.5 EN 902 EN Emperor Penguins Up Close Bredeson, Carmen 0.5 0.5 36787 Fish Frost, Helen 0.5 0.5 EN 9382 EN Little Runaway, The Hillert, Margaret 0.5 0.5 49858 Sit, Truman! Harper, Dan 0.5 0.5 EN 60939 Tiny Goes to the Library Meister, Cari 0.5 0.5 EN 36785 Cats Frost, Helen 0.6 0.5 EN 76670 Duck, Duck,Goose! (A Coyote's on the Loose!) Beaumont, Karen 0.6 0.5 EN 31833 Fathers Schaefer, Lola M. 0.6 0.5 EN 9364 EN Funny Baby, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9383 EN Magic Beans, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 83514 Puppy Mudge Finds a Friend Rylant, Cynthia 0.6 0.5 EN 88312 Puppy Mudge Wants to Play Rylant, Cynthia 0.6 0.5 EN 59439 Rosie's Walk Hutchins, Pat 0.6 0.5 EN 9391 EN Three Bears, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9392 EN Three Goats, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9393 EN Three Little Pigs, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9400 EN Yellow Boat, The Hillert, Margaret 0.6 0.5 9355 EN Cinderella at the Ball Hillert, Margaret 0.7 0.5 31818 Family Pets Schaefer, Lola M. -

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves Manual

Variable Star Classification and Light Curves An AAVSO course for the Carolyn Hurless Online Institute for Continuing Education in Astronomy (CHOICE) This is copyrighted material meant only for official enrollees in this online course. Do not share this document with others. Please do not quote from it without prior permission from the AAVSO. Table of Contents Course Description and Requirements for Completion Chapter One- 1. Introduction . What are variable stars? . The first known variable stars 2. Variable Star Names . Constellation names . Greek letters (Bayer letters) . GCVS naming scheme . Other naming conventions . Naming variable star types 3. The Main Types of variability Extrinsic . Eclipsing . Rotating . Microlensing Intrinsic . Pulsating . Eruptive . Cataclysmic . X-Ray 4. The Variability Tree Chapter Two- 1. Rotating Variables . The Sun . BY Dra stars . RS CVn stars . Rotating ellipsoidal variables 2. Eclipsing Variables . EA . EB . EW . EP . Roche Lobes 1 Chapter Three- 1. Pulsating Variables . Classical Cepheids . Type II Cepheids . RV Tau stars . Delta Sct stars . RR Lyr stars . Miras . Semi-regular stars 2. Eruptive Variables . Young Stellar Objects . T Tau stars . FUOrs . EXOrs . UXOrs . UV Cet stars . Gamma Cas stars . S Dor stars . R CrB stars Chapter Four- 1. Cataclysmic Variables . Dwarf Novae . Novae . Recurrent Novae . Magnetic CVs . Symbiotic Variables . Supernovae 2. Other Variables . Gamma-Ray Bursters . Active Galactic Nuclei 2 Course Description and Requirements for Completion This course is an overview of the types of variable stars most commonly observed by AAVSO observers. We discuss the physical processes behind what makes each type variable and how this is demonstrated in their light curves. Variable star names and nomenclature are placed in a historical context to aid in understanding today’s classification scheme. -

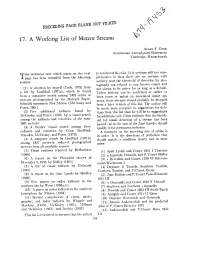

17. a Working List of Meteor Streams

PRECEDING PAGE BLANK NOT FILMED. 17. A Working List of Meteor Streams ALLAN F. COOK Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory Cambridge, Massachusetts HIS WORKING LIST which starts on the next is convinced do exist. It is perhaps still too corn- page has been compiled from the following prehensive in that there arc six streams with sources: activity near the threshold of detection by pho- tography not related to any known comet and (1) A selection by myself (Cook, 1973) from not sho_m to be active for as long as a decade. a list by Lindblad (1971a), which he found Unless activity can be confirmed in earlier or from a computer search among 2401 orbits of later years or unless an associated comet ap- meteors photographed by the Harvard Super- pears, these streams should probably be dropped Sehmidt cameras in New Mexico (McCrosky and from a later version of this list. The author will Posen, 1961) be much more receptive to suggestions for dele- (2) Five additional radiants found by tions from this list than he will be to suggestions McCrosky and Posen (1959) by a visual search for additions I;o it. Clear evidence that the thresh- among the radiants and velocities of the same old for visual detection of a stream has been 2401 meteors passed (as in the case of the June Lyrids) should (3) A further visual search among these qualify it for permanent inclusion. radiants and velocities by Cook, Lindblad, A comment on the matching sets of orbits is Marsden, McCrosky, and Posen (1973) in order. It is the directions of perihelion that (4) A computer search -

Meteor Shower Detection with Density-Based Clustering

Meteor Shower Detection with Density-Based Clustering Glenn Sugar1*, Althea Moorhead2, Peter Brown3, and William Cooke2 1Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 2NASA Meteoroid Environment Office, Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, AL, 35812 3Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Western Ontario, London N6A3K7, Canada *Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract We present a new method to detect meteor showers using the Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise algorithm (DBSCAN; Ester et al. 1996). DBSCAN is a modern cluster detection algorithm that is well suited to the problem of extracting meteor showers from all-sky camera data because of its ability to efficiently extract clusters of different shapes and sizes from large datasets. We apply this shower detection algorithm on a dataset that contains 25,885 meteor trajectories and orbits obtained from the NASA All-Sky Fireball Network and the Southern Ontario Meteor Network (SOMN). Using a distance metric based on solar longitude, geocentric velocity, and Sun-centered ecliptic radiant, we find 25 strong cluster detections and 6 weak detections in the data, all of which are good matches to known showers. We include measurement errors in our analysis to quantify the reliability of cluster occurrence and the probability that each meteor belongs to a given cluster. We validate our method through false positive/negative analysis and with a comparison to an established shower detection algorithm. 1. Introduction A meteor shower and its stream is implicitly defined to be a group of meteoroids moving in similar orbits sharing a common parentage. -

Stellarium User Guide

Stellarium User Guide Matthew Gates 25th January 2008 Copyright c 2008 Matthew Gates. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sec- tions, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". 1 Contents 1 Introduction 6 2 Installation 7 2.1 SystemRequirements............................. 7 2.2 Downloading ................................. 7 2.3 Installation .................................. 7 2.3.1 Windows ............................... 7 2.3.2 MacOSX............................... 7 2.3.3 Linux................................. 8 2.4 RunningStellarium .............................. 8 3 Interface Guide 9 3.1 Tour...................................... 9 3.1.1 TimeTravel.............................. 10 3.1.2 MovingAroundtheSky . 10 3.1.3 MainTool-bar ............................ 11 3.1.4 TheObjectSearchWindow . 13 3.1.5 HelpWindow............................. 14 3.1.6 InformationWindow . 14 3.1.7 TheTextMenu ............................ 15 3.1.8 OtherKeyboardCommands . 15 4 Configuration 17 4.1 SettingtheDateandTime .. .... .... ... .... .... .... 17 4.2 SettingYourLocation. 17 4.3 SettingtheLandscapeGraphics. ... 19 4.4 VideoModeSettings ............................. 20 4.5 RenderingOptions .............................. 21 4.6 LanguageSettings............................... 21 -

EPSC2015-482, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 Eeuropeapn Planetarsy Science Ccongress C Author(S) 2015

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 10, EPSC2015-482, 2015 European Planetary Science Congress 2015 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2015 Recent meteor showers – models and observations P. Koten (1) and J. Vaubaillon (2) (1) Astronomical Institute of ACSR, Ond řejov, Czech Republic, (2) Institut de mecanique Celeste et de Calcul des Ephemerides, Paris, France ([email protected] / Fax: +420-323-620263) Abstract 3. Meteor showers A number of meteor shower outbursts and storms Among the most studied meteor showers is the occurred in recent years starting with several Leonid Leonids due to recent return of their parent comet. storms around 2000 [1]. The methods of modeling Outbursts and storms between 1998 and 2002 and meteoroid streams became better and more precise. also another event in 2009 were observed and An increasing number of observing systems enabled analyzed. The Draconid outbursts in 2005 and 2011 better coverage of such events. The observers were also covered. Especially the latter was observed provide modelers with an important feedback on intensively using different instruments onboard two precision of their models. Here we present aircraft [4]. comparison of several observational results with the model predictions. 1. Introduction The double station observations using video technique are carried out by the Ondrejov observatory team for many years [2]. Besides the regular observations of the meteor showers the campaigns are also dedicated to predicted meteor storms and outbursts. The team participated to several international campaigns during recent Leonid meteor shower return as well as on the Draconid airborne campaign in 2011. The main goal of this experiment is the determination of the meteor trajectories and orbits and the meteor shower activity is also measured and compared with predictions. -

May / June 2010 Amateur Astronomy Club Issue 93.1/94.1 29°39’ North, 82°21’ West

North Central Florida’s May / June 2010 Amateur Astronomy Club Issue 93.1/94.1 29°39’ North, 82°21’ West Member Member Astronomical International League Dark-Sky Association NASA Early Morning Launch of Discovery STS-131 Provides Quite a Show! Photo Below: Taken in Titusville on SR 406 / 402 Causeway by Mike Lewis. The camera is a Nikon D2X with Nikon 400mm / f2.8 lens on automatic exposure (f8 @ 1/250s). “First night launch I’ve made it to in a while, and it was great.” - Mike Lewis Photo Below: Time-lapse photo by Howard Cohen taken from SW Gainesville (190 sec- onds long, beginning 6:22:52 a.m. EDT). “I like others was struck by the comet-like contrail that eventually followed the shuttle as it gained altitude.” - Howard Cohen Newberry Sports Complex and Observatory Rich Russin The President’s Corner As we head to press, work continues towards the establishment of an agree- ment between the AAC, the NSC, and the City of Newberry that would establish a permanent observing site on the grounds of the Newberry Sports Complex. The outcome will almost certainly be known before the next newsletter. For those of you not familiar with the project, the club has been offered an op- portunity to establish a base for both club and outreach events. Part of the pro- posal includes a permanent observing site, onsite storage, and possibly an ob- servatory down the road. In return, the club will provide an agreed upon number of outreach events and astronomy related support for the local school science programs. -

Chasing the Pole — Howard L. Cohen

Reprinted From AAC Newsletter FirstLight (2010 May/June) Chasing the Pole — Howard L. Cohen Polaris like supernal beacon burns, a pivot-gem amid our star-lit Dome ~ Charles Never Holmes (1916) ew star gazers often believe the North Star (Polaris) is brightest of all, even mistaking Venus for this best known star. More advanced star gazers soon learn dozens of Nnighttime gems appear brighter, forty-seven in fact. Polaris only shines at magnitude +2.0 and can even be difficult to see in light polluted skies. On the other hand, Sirius, brightest of all nighttime stars (at magnitude -1.4), shines twenty-five times brighter! Beginning star gazers also often believe this guidepost star faithfully defines the direction north. Although other stars staunchly circle the heavens during night’s darkness, many think this pole star remains steadfast in its position always marking a fixed point on the sky. Indeed, a popular and often used Shakespeare quote (from Julius Caesar) is in tune with this perception: “I am constant as the northern star, Of whose true-fix'd and resting quality There is no fellow in the firmament.” More advanced star gazers know better, that the “true-fix’d and resting quality”of the northern star is only an approximation. Not only does this north star slowly circle the northen heavenly pole (Fig. 1) but this famous star is also not quite constant in light, slightly varying about 0.03 magnitudes. Polaris, in fact, is the brightest appearing Cepheid variable, a type of pulsating star. Still, Polaris is a good marker of the north cardinal point.