Newsletter No 4 August 1984 • VALSPAN C )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ganspan Draft Archaeological Impact Assessment Report

CES: PROPOSED GANSPAN-PAN WETLAND RESERVE DEVELOPMENT ON ERF 357 OF VAALHARTS SETTLEMENT B IN THE PHOKWANE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Archaeological Impact Assessment Prepared for: CES Prepared by: Exigo Sustainability ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (AIA) ON ERF 357 OF VAALHARTS SETTLEMENT B FOR THE PROPOSED GANSPAN-PAN WETLAND RESERVE DEVELOPMENT, FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY, NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE Conducted for: CES Compiled by: Nelius Kruger (BA, BA Hons. Archaeology Pret.) Reviewed by: Roberto Almanza (CES) DOCUMENT DISTRIBUTION LIST Name Institution Roberto Almanza CES DOCUMENT HISTORY Date Version Status 12 August 2019 1.0 Draft 26 August 2019 2.0 Final 3 CES: Ganspan-pan Wetland Reserve Development Archaeological Impact Assessment Report DECLARATION I, Nelius Le Roux Kruger, declare that – • I act as the independent specialist; • I am conducting any work and activity relating to the proposed Ganspan-Pan Wetland Reserve Development in an objective manner, even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the client; • I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work; • I have the required expertise in conducting the specialist report and I will comply with legislation, including the relevant Heritage Legislation (National Heritage Resources Act no. 25 of 1999, Human Tissue Act 65 of 1983 as amended, Removal of Graves and Dead Bodies Ordinance no. 7 of 1925, Excavations Ordinance no. 12 of 1980), the -

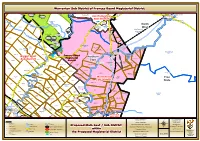

Phokwane Local Municipality

PHOKWANE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2007-2011 SECOND PHASE OF A DEVELOPMENTAL LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS IDP: Integrated Development Plan EPWP: Extended Public Works Program PMS: Performance Management System CDW: Community Development Worker MSM OF 1998: Municipal Structures Act of 1998 FBS: Free Basic Services MSM OF 2000: Municipal Systems Act of 2000 NGO: Non-Governmental Organization LED: Local Economic Development CBO: Community Based Organization MIG: Municipal Infrastructure Grant MFMA of 2003: Municipal Finance Management DME: Department of Minerals Energy Act of 2003 DEAT: Department of Environmental Affairs & RSA: Republic of South Africa Tourism WC: Ward Committee DOA: Department of Agriculture COC: Code of Conduct DLA: Department of Land Affairs LG: Local Government IT: Information Technology GIS: Geographic Information Systems MDG: Millennium Development Goal DLG&H: Department of Local Government & Housing FBDM: Frances Baard District Municipality DCTEA: Department of Conservation, Tourism, Environmental Affairs 2 FOREWORD BY THE MAYOR: Hon. Vuyisile Khen It is indeed both a pledge and honour that this sphere of government, which is at the coalface of service delivery, is entering its second phase of developmental local government. We do the latter with acknowledgement of the challenges we still face ahead, the ones we could not deal with in the first term given our limitation in terms of resources. We are mindful of the millennium goals targets in terms of provision of basic services coupled with the PGDS we need to reach, and we are ready and prepared to deliver with assistance from our sector departments. We further bank on our partnership with private through their investment which aims at creating employment opportunities and growing the local economy. -

Determining the Vitality of Urban Centres

The Sustainable World 15 Determining the vitality of urban centres J. E. Drewes & M. van Aswegen North West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa Abstract This paper will attempt to provide an encompassing Index of Vitality for urban centres. The Vitality Index’s© goal is to enable measurement of the general economic, social, physical, environmental, institutional and spatial performance of towns within a regional framework, ultimately reflecting the spatial importance of the urban centre. Towns have been measured in terms of numerous indicators, mostly in connection with social and economic conditions, over an extended period of time. The lack of suitable spatial indicators is identified as a significant shortcoming in the measurement of urban centres. This paper proposes the utilisation of a comprehensive index to measure the importance of an urban centre within a specific region. The Vitality Index© is consequently tested in a study area situated in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa. This study contributes in a number of ways to the measurement of urban centres, i.e. the shortcomings that are identified for the urban centres can be addressed by goal-specific policy initiatives, comprising a set of objectives and strategies to correct imbalances. The Vitality Index© also provides a basis for guiding national and regional growth policies, in the identification of urban centres with sustainable growth potential and vitality. Keywords: sustainability indicators, measuring urban centres, importance of urban centres, sustainable housing, spatial planning; policy, South Africa. 1 Introduction Various indicators have been designed and are recognised to provide a quantitative evaluation of an urban centre. Included are indicators describing economic growth, accessibility, sustainability, quality of life and environmental quality. -

14 Northern Cape Province

Section B:Section Profile B:Northern District HealthCape Province Profiles 14 Northern Cape Province John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipality (DC45) Overview of the district The John Taolo Gaetsewe District Municipalitya (previously Kgalagadi) is a Category C municipality located in the north of the Northern Cape Province, bordering Botswana in the west. It comprises the three local municipalities of Gamagara, Ga- Segonyana and Joe Morolong, and 186 towns and settlements, of which the majority (80%) are villages. The boundaries of this district were demarcated in 2006 to include the once north-western part of Joe Morolong and Olifantshoek, along with its surrounds, into the Gamagara Local Municipality. It has an established rail network from Sishen South and between Black Rock and Dibeng. It is characterised by a mixture of land uses, of which agriculture and mining are dominant. The district holds potential as a viable tourist destination and has numerous growth opportunities in the industrial sector. Area: 27 322km² Population (2016)b: 238 306 Population density (2016): 8.7 persons per km2 Estimated medical scheme coverage: 14.5% Cities/Towns: Bankhara-Bodulong, Deben, Hotazel, Kathu, Kuruman, Mothibistad, Olifantshoek, Santoy, Van Zylsrus. Main Economic Sectors: Agriculture, mining, retail. Population distribution, local municipality boundaries and health facility locations Source: Mid-Year Population Estimates 2016, Stats SA. a The Local Government Handbook South Africa 2017. A complete guide to municipalities in South Africa. Seventh -

2021 BROCHURE the LONG LOOK the Pioneer Way of Doing Business

2021 BROCHURE THE LONG LOOK The Pioneer way of doing business We are an international company with a unique combination of cultures, languages and experiences. Our technologies and business environment have changed dramatically since Henry A. Wallace first founded the Hi-Bred Corn Company in 1926. This Long Look business philosophy – our attitude toward research, production and marketing, and the worldwide network of Pioneer employees – will always remain true to the four simple statements which have guided us since our early years: We strive to produce the best products in the market. We deal honestly and fairly with our employees, sales representatives, business associates, customers and stockholders. We aggressively market our products without misrepresentation. We provide helpful management information to assist customers in making optimum profits from our products. MADE TO GROW™ Farming is becoming increasingly more complex and the stakes ever higher. Managing a farm is one of the most challenging and critical businesses on earth. Each day, farmers have to make decisions and take risks that impact their immediate and future profitability and growth. For those who want to collaborate to push as hard as they can, we are strivers too. Drawing on our deep heritage of innovation and breadth of farming knowledge, we spark radical and transformative new thinking. And we bring everything you need — the high performing seed, the advanced technology and business services — to make these ideas reality. We are hungry for your success and ours. With us, you will be equipped to ride the wave of changing trends and extract all possible value from your farm — to grow now and for the future. -

NC Sub Oct2016 FB-Warrenton.Pdf

# # !C # # ### ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # ^!C # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # #!C# # # # !C# ^ # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # #^ # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # ## !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # # # # !C # # !C# # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # #^ !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C ## # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # !C # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## ## # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # ## # # !C # # # # # # # ^ # # # # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # !C # !C # #!C # # # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # #### # # # !C # # !C# # # # !C # ## !C # # # # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # !C ## !C## # # # ## # !C # ## # !C# ## # # !C ## # !C # # ^ # ## # # # !C# ^ # # !C # # # !C ## # #!C ## # # # # # # # # ## # # # ## !C# ## # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # ^ # # !C # ## # ## # # # # !. # # # # # !C -

Nc Travelguide 2016 1 7.68 MB

Experience Northern CapeSouth Africa NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Tel: +27 (0) 53 832 2657 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 Email:[email protected] www.experiencenortherncape.com 2016 Edition www.experiencenortherncape.com 1 Experience the Northern Cape Majestically covering more Mining for holiday than 360 000 square kilometres accommodation from the world-renowned Kalahari Desert in the ideas? North to the arid plains of the Karoo in the South, the Northern Cape Province of South Africa offers Explore Kimberley’s visitors an unforgettable holiday experience. self-catering accommodation Characterised by its open spaces, friendly people, options at two of our rich history and unique cultural diversity, finest conservation reserves, Rooipoort and this land of the extreme promises an unparalleled Dronfield. tourism destination of extreme nature, real culture and extreme adventure. Call 053 839 4455 to book. The province is easily accessible and served by the Kimberley and Upington airports with daily flights from Johannesburg and Cape Town. ROOIPOORT DRONFIELD Charter options from Windhoek, Activities Activities Victoria Falls and an internal • Game viewing • Game viewing aerial network make the exploration • Bird watching • Bird watching • Bushmen petroglyphs • Vulture hide of all five regions possible. • National Heritage Site • Swimming pool • Self-drive is allowed Accommodation The province is divided into five Rooipoort has a variety of self- Accommodation regions and boasts a total catering accommodation to offer. • 6 fully-equipped • “The Shooting Box” self-catering chalets of six national parks, including sleeps 12 people sharing • Consists of 3 family units two Transfrontier parks crossing • Box Cottage and 3 open plan units sleeps 4 people sharing into world-famous safari • Luxury Tented Camp destinations such as Namibia accommodation andThis Botswanais the world of asOrange well River as Cellars. -

Consumer Goods Crime Risk Initiative 05 July 2019 Weekly Situational

Consumer Goods Crime Risk Initiative 28 May 2021 Weekly Situational Analysis Report TopicWorx Alerts – Unrest TopicWorx Alerts – Anticipated Events The below section highlights unrest reported by TopicWorx to the The below section highlights unrest reported by TopicWorx to the CGCRI, which have been reported over the course of the week CGCRI over the course of the week • Demonstrations foreseen at Daveyton Mall (Daveyton, Benoni, Gauteng) from May 2021 owing to the Strike Action demand for employment opportunities - operational risks anticipated Protest March 1% 4% • Travel and security risks foreseen during anticipated demonstrations at Matatane Secondary School (Cool Air, KwaZulu-Natal) from May 2021 owing to the demand for additional teaching staff • Demand for electricity expected to result in protest action in Noordgesig (Soweto, Gauteng) from May 2021 - travel and security risks foreseen • SATAWU demonstrations expected at the Limpopo Provincial Treasury and GNT Head Office (Polokwane Central, Limpopo) from May 2021 owing to several demands - risks to business operations foreseen • Negotiations between SAMWU, IMATU and SALGA expected to continue at SALGBC from 31/05/2021 following revised wage offer by SALGA - possible industrial action anticipated from July 2021 expected to result in operational risks • Travel and security risks foreseen during anticipated protest action in Sebokeng (Gauteng) from May 2021 owing to demand for electricity • Protest action expected in Jan Kempdorp (Northern Cape) from May 2021 owing to the demand -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Northern Cape

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Northern Cape Permit Number Primary Name Address 202103969 Coleberg Correctional Petrusville road, services Colesberg Centre, Colesberg Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103950 Upington Clinic Schroder Street 52 Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103841 Assmang Blackrock Sering Avenue Mine OHC J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103831 Schmidtsdrift Satellite Sector 4 Clinic Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103744 Assmang Khumani Mine 1 Dingleton Road, Wellness Centre Dingleton J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103270 Prieska Clinic Bloekom Street, Prieska, 8940 Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103040 Kuyasa Clinic Tutuse Street Kuyasa Colesberg Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103587 Petrusville Clinic Thembinkosi street, 1928 New Extention Petrusville Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103541 Keimoes CHC Hoofstraat 459 ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103525 Griekwastad 1 Moffat Street (Helpmekaar) CHC Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape Updated: 30/06/2021 202103457 Medirite Pharmacy - Erf 346 Cnr Livingstone Kuruman Road & Seadin Way J T Gaetsewe DM Northern Cape 202103444 Progress Clinic Bosliefie Street,Progress Progress,Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103443 Sarah Strauss Clinic Leeukop Str. Rosedale,Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103442 Louisvaleweg Clinic Louisvale Weg Upington ZF Mgcawu DM Northern Cape 202103441 Lehlohonolo Adams Monyatistr 779 Bongani Clinic Douglas Pixley ka Seme DM Northern Cape 202103430 Florianville (Floors) Stokroos Street, Clinic Squarehill Park, Kimberley -

20201101-Nw-Advert Taung Sheriff Service Area.Pdf

TTaauunngg SShheerriiffff SSeerrvviiccee AArreeaa GLENCAIRN GLENRED CASSEL WAAIHOEK KAMEELBOOM DE RUST DORENPOORT BONAPARTE AARBOSCH BERNAUW KAREE PUT LOSASA VREDEBURG DOORNPAN LOT 35 265 LOT 40 270 WELGEVONDEN SHIPTON Bendell SP BATLHARO BA GA Ga-Madudu SP BRUL PAN DRIEPAN KLONDIKE Vryburg SP EENZAAMHEID PENDER VLAKTE KAMEEL MIDDELPAN VLAKTE LIMA WOODHOUSE BRANDWAGT LOT 36 LOT 30 RUSTFONTEIN NOOITGEDACHT KOBOGA HAMBURG KLIP ROSENDAL HARTKLIP MOOIFONTEIN MAKOUSPAN LOT BATLHAPING BENDELL PHADIMA Lebonkeng SP RAND COCHNAGAR Letlhakajaneng SP VLAKTE RETREAT OOST WEDERGEVONDEN DOORNPAN 29 VLIEGENKRAAL KEANG WILDE WATERLOO KLIPRAND JALA LOT BA GA SEHUNELO VOGEL PAN LOT 38 ALS KAMEELFONTEIN FRANKFORT KAREEBOOM JALA 31 Mogobing SP Ga-Makgatle SP TWISTFONTEIN GOEDGEVONDEN MOOIFONTEIN WELGEVONDEN DEFENCE LOT 25 9 Ramatele SP LAAGTE SWEET FONTEIN EXCELSIOR KOPPIESVLEY Ga-sehunelo SP WATERLOO MOOIFONTEIN WEST HALLETSHOOP DUNOON SECRETARIS HOME GROENPAN ZOETFONTEIN Bothithong Kagisano NU PUTPAN TAKWANEN WEST DOORNBULT LOT 22 ESSILMONT GLENORRA Segwaneng SP BEAUFORT VLAKTE KLIPVLAKTE NAZARETH EDINBURGH CHAMPIONS LOCKERBIE LOT Kakoje SP ^!. Bothithong KOPJESLAAGTE NATIVE RESERVE BLAUW LINDESRUS LOT 26 HERMITAGE SP 45 ELIM SCHOONDAL Matshaneng SP DRIEPOORT KLOOF BOSCH ZOET EN LOT 21 LANGMEAD DOORNFONTEIN Thakwane SP WELTEVREDEN MARGARETHALOT DEERWABRDATLHAPING BOO MOTITON Dithakong SP WELGEVONDEN KNOPPIES KUIL SMART ZOETVLEI 19 KOPPIESFONTEIN Nkajaneng SP VLAKTE HARTSBOOM ZWARTKRANS VAN VREDES JACOBSDAL R506 PHUDUHUTSWANA Majankeng BORTHWICK ST ELDORADO -

Windsorton-Publication-Web.Pdf

1 2 3 The Institute for Justice and Reconciliation contributes to the building of fair, democratic and inclusive societies in Africa before, during and after political transition. It seeks to advance dialogue and social transformation. Through research, analysis, community intervention, spirited public debate and grassroots encounters, the Institute’s work aims to create a climate in which people in divided societies are willing to build a common, integrated vision. The Institute is committed to peacemaking at every level of Windsorton society, by breaking down old boundaries and reshaping social paradigms. Reakantswe Intermediate School ISBN 978-1-920219-58-1 105 Hatfield Street Gardens Cape Town 8001 Photo’s © Cecyl Esau 2013, 2014, 2015 Design & Layout by Talia Simons Printed by TopCopy [email protected] 4 contents Overview of the Project . 8 Mmereki Mothupi . 46 Bennet Phillimon . 15 Mina Ntshakane . 48 Mpho Fisher . 18 Elton Raadt . 50 Lebogang Olebogeng . 19 Pulane Saul . 54 Ipeleng Jacobs . 21 Regopotswe Theophilus Otsheleng . 56 Tshwaro Mohibidu . 24 Jessica Mphahlele . 58 Thato Sethlabi . 27 Beldad Makhado Gaapare . 60 Abigail Teledimo . 29 Gopolang Alfred Moilwe . 62 Shadrack ‘Neo’ Ikaneng . 30 Nomahlubi Mabote . 63 Tiny Modirapula . 32 Aobakwe Riet . 66 Richard Masopa Mabe . 36 Tumo Sunduzo . 68 Kelebogile ‘Mamie’ Stuurman . 40 Tshepiso Olivia Ndlovu . 69 Thabiso Lebeko . 42 Koketso Kale . 70 Polediso Nkabu . 44 overview of the project This project forms part of the Schools’ Oral History project (SOHP) of the Building an Inclusive Society programme at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) based in Cape Town. The youth population of South Africa constitutes more than half of South Africa's young democratic state. -

Wetland Report | 2017

FRANCES BAARD DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY WETLAND REPORT | 2017 LOCAL ACTION FOR BIODIVERSITY (LAB): WETLANDS SOUTH AFRICA Biodiversity for Life South African National Biodiversity Institute Full Program Title: Local Action for Biodiversity: Wetland Management in a Changing Climate Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Southern Africa Cooperative Agreement Number: AID-674-A-14-00014 Contractor: ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability – Africa Secretariat Date of Publication: September 2017 Author: R. Fisher DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. FOREWORD Wetlands are important features in the landscape The Frances Baard District Municipality, in that provide numerus beneficial services for people partnership with various stakeholders, is committed and nature. Some of the valuable functions include to the maintenance and protection of our wetlands protecting an improving water quality, providing as functioning ecosystems. It is our wish that the natural habitats, storing floodwaters, maintaining implementation of this report will create further surface water during dry periods and aesthetic open awareness amongst our communities and local space. authorities. Wetlands are not only crucial for the Most of the wetlands of the Frances Baard local tourism industry, but the conservation of these District may usually appear dry, dependant on natural assets is also crucial to ensure that they are seasonal rainwater when they briefly flourish full preserved for the health and recreational benefit of of life. Other wetlands remain wet for longer, communities. particularly those receiving treated sewerage such I would like to take this opportunity to express as Ganspan in Jan Kempdorp and the world-famous my sincere gratitude to ICLEI Africa for their Kamfersdam north of Kimberley.