The Living Parable of the Peasant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholic Scripture Study Series I

CATHOLIC SCRIPTURE STUDY Catholic Scripture Study Notes written by Sister Marie Therese, are provided for the personal use of students during their active participa- tion and must not be loaned or given to others. SERIES I THE GOSPEL OF LUKE AND ACTS OF THE APOSTLES Lesson 2 Commentary Luke Lesson 3 Questions Luke 1 THE GOOD NEWS OF JESUS Luke I. INTRODUCTION TO THE GOSPELS • as a Jewish authority figure, a Pharisee or Sadducee? A. The World Situation at Jesus’ Time. One Empire, the Roman, controlled the countries No, Jesus came humbly, and began a ministry around the Mediterranean Sea (most of Europe), primarily to the needy, the powerless. He: and some of Africa. • fed the hungry • forgave sinners Palestine, the land of the Jewish people, ex- • healed the sick and the tormented tended about 150 miles long, and 30-50 miles • was a friend to the poor and the outcast, wide. It was a country smaller than the state of the blind, the lame, the paralyzed, tax col- Massachusetts. It was governed by Roman offi- lectors and prostitutes. cials and under Roman laws, but it was also under another Law—the Law of God, coming from the The death of Jesus was highly predictable, un- revelation of Himself to Abraham and his de- der the circumstances; supernaturally, it was the scendants—the Israelites. This law was taught and main event of our salvation. enforced by the Sanhedrin, composed of the priests, the scholars (the scribes), and the Jewish The Resurrection of Jesus was unpredictable leaders—Pharisees and Sadducees. and unbelieved by many; the Father’s gift of Jesus was irrevocable and definitive. -

The Rich Fool

"Scripture taken from the NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE®, © Copyright 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation Used by permission." (www.Lockman.org) The Rich Fool Introduction. 1. Luke records these words in Luke 12:13-14. LUK 12:13 And someone in the crowd said to Him, "Teacher, tell my brother to divide the family inheritance with me." LUK 12:14 But He said to him, "Man, who appointed Me a judge or arbiter over you?" a. The account of The Rich Fool is unique and is found only in the gospel of Luke. b. Someone from the crowd asks Jesus to be an “arbiter” between he and his brother, but Jesus rejected that role. c. Jesus indicated He did not come to settle such disputes. (Lk. 12:14). d. He had come to seek and save the lost. (Lk. 19:10). 2. Jesus uses this occasion to warn against “every form of greed” [covetousness] (Lk. 12:15). LUK 12:15 And He said to them, "Beware, and be on your guard against every form of greed; for not even when one has an abundance does his life consist of his possessions." C “pleonexia” [pleh ah neks ee ah] - “greediness, covetousness.” C Lit. “every form of greediness or covetousness.” a. What the brother wanted could be settled by the courts. 1) The Old Testament gave clear teaching regarding the inheritance of property. (Deut. 21:15-17; Num. 27:1-11; 36:7-9). 2) The circumstances of the dispute are not given, and are not important to the lesson Jesus wanted to stress. -

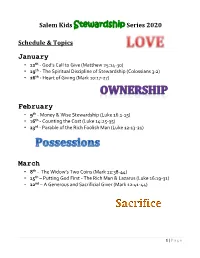

Sunday School Lesson (Mark 10:17-27) Stewardship for Kids Ministry-To-Children.Com/Heart-Of-Giving-Lesson

Salem Kids Stewardship Series 2020 Schedule & Topics January • 12th - God’s Call to Give (Matthew 25:14-30) • 19th - The Spiritual Discipline of Stewardship (Colossians 3:2) • 26th - Heart of Giving (Mark 10:17-27) February • 9th - Money & Wise Stewardship (Luke 16:1-15) • 16th - Counting the Cost (Luke 14:25-35) • 23rd - Parable of the Rich Foolish Man (Luke 12:13-21) March • 8th - The Widow’s Two Coins (Mark 12:38-44) • 15th – Putting God First - The Rich Man & Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31) • 22nd – A Generous and Sacrificial Giver (Mark 12:41-44) 1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Lesson: God’s Call to Give (Matthew 25:14-30) Stewardship for Kids ministry-to-children.com/stewardship-lesson-1 Scripture: Matthew 25:14-30 Supplies: Pencils, paper, yellow circles of construction paper Lesson Opening: What is Stewardship? Ask: Has anyone ever heard the word “Steward” before? What do you think it means? (A steward is someone who takes care of another person’s property.) Ask: What does it mean to be responsible for something? Ask: What are some things that you are responsible for? Ask: Did you know that God has made each of us stewards? We are all stewards over the things that God entrusts to us. Say: We’ll hear a parable, or story, about 3 servants who were responsible for their master’s money. Pray that God would open their hearts to His Word today and that He would stir our hearts to be good stewards of His creation and that we would give back to Him with thankful hearts. -

Deas Eddie 1984

THE PARABLE OF THE RICH FOOL; HISTORY OF INTERPRETATION AND EXEGESIS Submitted by Eddie Deas, III, M.A. May 1, 1984 APPROVED Faculty:ulty Advisorj DATE: APPROVEDi= Vice Pres.'Fo^r TYcad^ic/^^ervices DATE: 0'S7/D: TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. INTERPRETATION HISTORY OF PARABLES 5 III. EXEGESIS OF LUKE 12:13-21 9 CONCLUDING REMARKS . ... .. 2 2 BIBLIOGRAPHY 24 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION I£ any person is just passingly acquainted with the Gospels(Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) then he or she would readily agree that Jesus was a master in the usage of oral communication forms. His words had a power to move, change and shape peoples lives. Jesus had a way of "turning a phrase" quite unlike any of the other personalities of his day. In many respects Jesus' teachings-while appearing to re¬ semble that of other teachers(Rabbis)-was often a thing apart. As a teacher Jesus utilized varying oral forms; one of his most often used forms was that of the parable. It was obvious that Jesus was adept at utilizing this literary form, but the question remains as to what purpose. A central question surrounding parable interpretation today is precisely this concern. The term parable comes from the Greek word Parabole and in Hellenistic Greek it had a meaning that was closely related to the Hebrew word Mashal. This Hebrew word, Mashal often had a wide range of applications; including proverbs, riddles, wise sayings, extended metaphors, and prophetic sayings. Similarly Joachim Jeremias wrote: "This word (parabole) may mean in the common speech. -

Luke Study Guide

Going Deeper Luke-Acts There is nothing quite as powerful as studying the life of Jesus. My hope is that we slow down and take the time to watch, listen, and experience Jesus interacting with hurting people, walking with the Father, and changing the world through his love, compassion, and power. Everyone who interacts with Jesus is changed! This study is designed for us to engage in that life changing interaction. Jesus establishes his disciples and puts them on mission. We are asking Jesus to do the same in and through us. May we fall more in love with Him, worship Him, and follow His lead. Please enjoy your time in God’s Word with the Savior. Your pastors serve you with excitement and joy. We can’t wait to experience how God will continue to use His Word to shape and grow us all. For the love of the Savior and the fulfillment of His mission, Mike Graham Pastor of Group Life The Design and Intention of this Study The study guide that has been prepared is not a verse by verse study of Luke. Luke is the largest New Testament book and such a study could be quite overwhelming to develop or use. The intention of this study guide is to help the reader stop, watch, and learn from Jesus in the book of Luke. The study guide will focus on aspects of Jesus’ life, ministry, and teaching. Quite a bit of Luke will be addressed, but not every difficult verse and concept will be explained and taught. -

Outline for the Gospel of Saint Luke

THE GOSPEL OF LUKE The Inclusiveness of this Gospel Addressed to a Greek 10 And the angel said to them, "Be not afraid; for behold, I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people Luke 2:10 (RSV) “ a light for revelation to the Gentiles, and for glory to Your people Israel." Luke 2:32 The Gospel of Mary 1:26-38 The Annunciation 1:39-56 The Visitation 1:46-55 The Magnificat The Gospel of Forgiveness Forgiving of Sinful Woman 7:36-50 The parable of the Merciful Father 15:11-32 The parable of the Pharisee and Tax-collector 18:9-14 The blind man on the road near Jericho 18:35-43 And Jesus said, "Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do." Luke 23:34 The Good Thief And he said, "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom." And [Jesus] said to him, "Truly, I say to you, today you will be with Me in Paradise." Luke 23:42-43 (RSV) The Gospel of the Holy Spirit 34 And Mary said to the angel, "How shall this be, since I have no husband?" 35 And the angel said to her, "The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be called holy, the Son of God. Luke 1:34-35 (RSV) 41 And when Elizabeth heard the greeting of Mary, the babe leaped in her womb; and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit 42 and she exclaimed with a loud cry, "Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb! Luke 1:41-42 (RSV) 25 Now there was a man in Jerusalem, whose name was Simeon, and this man was righteous and devout, looking for the consolation of Israel, and the Holy Spirit was upon him. -

“The Parable of the Rich Fool” (Luke 10:25-37) Dan Collison September

The Parables of Jesus Provocations in Wisdom “The Parable of the Rich Fool” (Luke 10:25-37) Dan Collison September 1, 2019 SCRIPTURE 13 Someone in the crowd said to him, “Teacher, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me.” 14 Jesus replied, “Man, who appointed me a judge or an arbiter between you?”15 Then he said to them, “Watch out! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; life does not consist in an abundance of possessions.” 16 And he told them this parable: “The ground of a certain rich man yielded an abundant harvest. 17 He thought to himself, ‘What shall I do? I have no place to store my crops.’ 18 “Then he said, ‘This is what I’ll do. I will tear down my barns and build bigger ones, and there I will store my surplus grain. 19 And I’ll say to myself, “You have plenty of grain laid up for many years. Take life easy; eat, drink and be merry.”’ 20 “But God said to him, ‘You fool! This very night your life will be demanded from you. Then who will get what you have prepared for yourself?’ 21 “This is how it will be with whoever stores up things for themselves but is not rich toward God.” 22 Then Jesus said to his disciples: “Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat; or about your body, what you will wear. 23 For life is more than food, and the body more than clothes. 24 Consider the ravens: They do not sow or reap, they have no storeroom or barn; yet God feeds them. -

Sunday School@Home – the Parable of the Rich Fool Lesson Background This Lesson Is Based on One of the Many Recorded Parables

Sunday School@Home – The Parable of the Rich Fool Lesson Background This lesson is based on one of the many recorded parables of Jesus. Parables are sometimes seen as moral tales like fables but they have much more to offer than a simple lesson of right and wrong. The parable of rich fool speaks to greed, self-concern and lack of compassion and sharing. Lesson Plan Read/Paraphrase: Jesus was a great teacher. He told stories using familiar objects and activities that the listeners of his day could understand. He sometimes told stories called parables. Today we are going to read and discuss The Parable of the Rich Fool. Younger children – Read/Paraphrase the children’s Bible version of our parable. It is at the end of this email. We are using the text from The Read-Aloud Bible Stories by Ella K. Lindvall for this lesson. This parable does not appear in our usual Milton Bible. Grades 1,2 – Show the children Luke 12:13-21 in an adult Bible. Read/Paraphrase the story from the children’s Bible at the end of this email. Share: Jesus told this parable to the people of his time long ago. These people would understand being rich because as a farmer you were good at growing wheat and having much of this crop to store. Ask: Do you like this parable? What did the farmer do well? What are somethings the farmer did not think about? Do you think building bigger barns was a good idea? What are some other things the farmer could have done with his wheat? Share: We all have choices about how we use our blessings. -

The Interpretation of Parables

Grace Theological Journal 11.2 (1970) 3-20 Copyright © 1970 by Grace Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. THE INTERPRETATION OF PARABLES VERNON D. DOERKSEN Assistant Professor of Theology and New Testament Arizona Bible College The striking importance of the parabolic method of teaching in Jewish thinking can be seen from this passage in the Apocrypha: But he that giveth his mind to the law of the most High, and is occupied in the meditation thereof, will seek out the wisdom of all the ancient, and be occupied in prophecies. He will keep the sayings of the renowned men: and where subtil parab1es are, he will be there also. He will seek out the secrets of grave sentences, and be conversant in dark parables (Eccles. 39:1-3). Our Lord made ready use of the parabolic method of teaching to the extent that Mark comments "but without a parable spake he not unto them" (4:34). The parables are not mere human tales; they are teachings of the Son of God, the One to whom the crowd listened gladly (Mk. 12:37). Of Him it is declared, "...the people were astonished at his doctrine: for he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes" (Matt. 7:28, 29). Of the parables, Armstrong writes: Indeed, they are sparks from that fire which our Lord brought to the earth (Lk. xii. 49)--the message of One who was 'a prophet...and more than a prophet' (Mk. xi.9; Lk. vii. 16)1 Christ's parables are not of mere man. -

RICH FOOL Luke 12:13-23

PARABLE: RICH FOOL Luke 12:13-23 STRUCTURE Key-persons: Jesus, and the man who interrupted him; in the parable: the rich man Key-location: Region of Perea Key-repetitions: • Life: life does not consist in possessions (Lk 12:15); don’t worry about life (Lk 12:23); life is more than food and clothes (Lk 12:23). • Possessions: life does not consist in having possessions (Lk 12:15); man’s farm, crops, and barn (Lk 12:16); bigger barns (Lk 12:18); good things stored up (Lk 12:18-19); a fool stores up material riches for himself, but is not rich in God’s sight (Lk 12:21). • Inheritance: one brother wanted his share of the inheritance (Lk 12:13); God asked the rich man who would get what he accumulated after his death (Lk 12:21). Key-attitudes: • Brother’s greed, anger, arrogance, and impatience as he interrupted Jesus. • Rich man’s satisfaction with possessions. • Rich man’s foolish arrogance. Initial-situation: Jesus' third year of public ministry began when King Herod ordered the murder of John the Baptist. The people were furious with King Herod. After Jesus multiplied the bread and fish and fed 5,000 men, the people wanted to annihilate King Herod and crown Jesus. When Jesus refused the people’s demand to lead a popular revolution, the people felt betrayed by Jesus. That ended his popularity with the multitudes. The religious leaders' antagonism toward Jesus increased. The people flip-flopped between excitement for Jesus when he performed a miracle, and anger toward Jesus when they didn't like his teaching. -

Faithful Managers For

Stewardship Principle #4 Faithful Managers For God “Whoever can be trusted with very little can also be trusted with much, and whoever is dishonest with very little will also be dishonest with much.” “Investing Your Treasure for Christ II” Luke 16:10 (NIV) Luke 12:13-21; Malachi 3:6-12 Pastor Gary Barber III. The Basics of Tithing March 17, 2013 Tithing was practiced before the Law of Moses I. The Parable of the Rich Fool – Luke 12:13-21 o Genesis 14:18-20; 28:20-22 “And he told them this parable: “The ground of a certain rich man yielded an Tithing was incorporated into the Law of Moses abundant harvest…. Then he said, ‘This is what I’ll do. I will tear down my o Lev. 27:30-33; Num. 18:21-24; Deut. 14:21-29 barns and build bigger ones, and there I will store my surplus grain…. “But God said to him, ‘You fool! This very night your life will be demanded from you. Then who will get what you have prepared for yourself?’ “This is how it Jesus affirmed tithing will be with whoever stores up things for themselves but is not rich toward o Matthew 23:23; Luke 11:42 God.”” Luke 12:16, 18, 20-21 (NIV) God promises unique blessings to those who tithe “Bring the whole tithe into the storehouse, so that there may be food in My Question: Are you rich towards God? house, and test Me now in this,” says the Lord of hosts, “if I will not open for you the windows of heaven and pour out for you a blessing until it overflows. -

The Rich Fool Lesson Plan Key Verses: (Luke 12:16-21) Objectives

Parables of Jesus Our Stay-at -Home series is about the Parables Jesus told. Jesus used the parables to explain to us concepts that may otherwise be difficult to understand. Over the next several weeks we will look at the earthly stories and explain and apply the heavenly meaning that goes with them. I have included a short story video for this lesson. Please use the link below to access the video. Link to the Story Video - The Rich Farmer - https://youtu.be/Pcg3SSZpVnI (copy and paste into the search engine) 1 The Rich Fool Lesson Plan Key Verses: (Luke 12:16-21) Objectives: 2’s&3’s - To be introduced to the concept of a parable. To learn the parable of the Rich Fool 4’s&5’s - To be introduced to the concept of a parable. To learn the parable of the Rich Fool K & 1st - To learn a Parable is an earthly story with a heavenly meaning. To understand the parable of the Rich Fool. To learn to Put God First. 2nd & 3rd - To learn a Parable is an earthly story with a heavenly meaning. To understand the parable of the Rich Fool. To learn to Put God First. 4th & up - To learn a Parable is an earthly story with a heavenly meaning. To understand the parable of the Rich Fool. To learn to Put God First. Application: 2’s&3’s - I can Put God First. 4’s&5’s - I can Put God First. K & 1st - I can choose the right priority and Put God First.