A Socio-Narratological Approach to the Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luke 16:19-31)

“A Final Word from Hell” (Luke 16:19-31) If you’ve ever flown on an airplane you’ve probably noticed that in the seat pocket ahead of you is a little safety information card. It contains lots of pictures and useful information illustrating what you should do if, for example, the plane you’re entrusting your life with should have to ditch in the ocean. Not exactly the kind of information most people look forward to reading as they’re preparing for a long flight. The next time you’re on an airplane, look around and see how many people you can spot actually reading the safety cards. Nowadays, I suspect you’ll find more people talking or reading their newspaper instead. But suppose you had a reason to believe that there was a problem with the flight you were on. Suddenly, the information on that card would be of critical importance—what seemed so unimportant before takeoff could mean the difference between life and death. In the same way, the information in the pages of God’s Word is critically important. The Bible contains a message that means the difference between eternal life and death. Yet, for many of us, our commitment to the Bible is more verbal than actual. We affirm that the Bible is God’s Word, yet we do not read it or study it as if God was directly communicating to us. If left with a choice, many of us would prefer to read the newspaper or watch TV. Why is this? Certainly one reason for this is that there is not a sense of urgency in our lives. -

Sept. 29 – the Invisible Challenge Luke 16:19-31 the Story of the Rich

Sept. 29 – The Invisible Challenge Luke 16:19-31 The story of the rich man and Lazarus is another of those well-known parables of Jesus that we often hear with selective hearing. We listen to those parts that comfort us and ignore those parts that challenge. What I mean is that often we first of all define, in our minds, the word rich. We are never in that category. Warren Buffet or Bill Gates, they are rich. This parable is about them and the other 1% group in our nation and how they should act. We inwardly smile that they are getting a “talking too” and hope they listen and treat the poor better than now is the case. We rarely place ourselves in Lazarus’ shoes and ask, “Is this story of Jesus for us?” What I want to do today is to have this parable of Jesus confront us and our actions and our assumptions. Look at the attitude of the rich man towards Lazarus. It is clearly shown in this painting. Lazarus is seen just outside the door of the rich man’s kitchen. He’s literally right there, not a full step away. But you have to look for him. The painting is so full of the riches of this kitchen, that Lazarus, though right at the door, is hard to see at all. This parable is a reminder for us to think about all those we interact with on a daily basis. Too often some become invisible. We don’t really see them or their needs; they are just there, part of the fabric of life. -

Catholic Scripture Study Series I

CATHOLIC SCRIPTURE STUDY Catholic Scripture Study Notes written by Sister Marie Therese, are provided for the personal use of students during their active participa- tion and must not be loaned or given to others. SERIES I THE GOSPEL OF LUKE AND ACTS OF THE APOSTLES Lesson 2 Commentary Luke Lesson 3 Questions Luke 1 THE GOOD NEWS OF JESUS Luke I. INTRODUCTION TO THE GOSPELS • as a Jewish authority figure, a Pharisee or Sadducee? A. The World Situation at Jesus’ Time. One Empire, the Roman, controlled the countries No, Jesus came humbly, and began a ministry around the Mediterranean Sea (most of Europe), primarily to the needy, the powerless. He: and some of Africa. • fed the hungry • forgave sinners Palestine, the land of the Jewish people, ex- • healed the sick and the tormented tended about 150 miles long, and 30-50 miles • was a friend to the poor and the outcast, wide. It was a country smaller than the state of the blind, the lame, the paralyzed, tax col- Massachusetts. It was governed by Roman offi- lectors and prostitutes. cials and under Roman laws, but it was also under another Law—the Law of God, coming from the The death of Jesus was highly predictable, un- revelation of Himself to Abraham and his de- der the circumstances; supernaturally, it was the scendants—the Israelites. This law was taught and main event of our salvation. enforced by the Sanhedrin, composed of the priests, the scholars (the scribes), and the Jewish The Resurrection of Jesus was unpredictable leaders—Pharisees and Sadducees. and unbelieved by many; the Father’s gift of Jesus was irrevocable and definitive. -

06.07 Holy Saturday and Harrowing of Hell.Indd

Association of Hebrew Catholics Lecture Series The Mystery of Israel and the Church Spring 2010 – Series 6 Themes of the Incarnation Talk #7 Holy Saturday and the Harrowing of Hell © Dr. Lawrence Feingold STD Associate Professor of Theology and Philosophy Kenrick-Glennon Seminary, Archdiocese of St. Louis, Missouri Note: This document contains the unedited text of Dr. Feingold’s talk. It will eventually undergo final editing for inclusion in the series of books being published by The Miriam Press under the series title: “The Mystery of Israel and the Church”. If you find errors of any type, please send your observations [email protected] This document may be copied and given to others. It may not be modified, sold, or placed on any web site. The actual recording of this talk, as well as the talks from all series, may be found on the AHC website at: http://www.hebrewcatholic.net/studies/mystery-of-israel-church/ Association of Hebrew Catholics • 4120 W Pine Blvd • Saint Louis MO 63108 www.hebrewcatholic.net • [email protected] Holy Saturday and the Harrowing of Hell Whereas the events of Good Friday and Easter Sunday Body as it lay in the tomb still the Body of God? Yes, are well understood by the faithful and were visible in indeed. The humanity assumed by the Son of God in the this world, the mystery of Holy Saturday is obscure to Annunciation in the womb of the Blessed Virgin is forever the faithful today, and was itself invisible to our world His. The hypostatic union was not disrupted by death. -

The Rich Fool

"Scripture taken from the NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE®, © Copyright 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation Used by permission." (www.Lockman.org) The Rich Fool Introduction. 1. Luke records these words in Luke 12:13-14. LUK 12:13 And someone in the crowd said to Him, "Teacher, tell my brother to divide the family inheritance with me." LUK 12:14 But He said to him, "Man, who appointed Me a judge or arbiter over you?" a. The account of The Rich Fool is unique and is found only in the gospel of Luke. b. Someone from the crowd asks Jesus to be an “arbiter” between he and his brother, but Jesus rejected that role. c. Jesus indicated He did not come to settle such disputes. (Lk. 12:14). d. He had come to seek and save the lost. (Lk. 19:10). 2. Jesus uses this occasion to warn against “every form of greed” [covetousness] (Lk. 12:15). LUK 12:15 And He said to them, "Beware, and be on your guard against every form of greed; for not even when one has an abundance does his life consist of his possessions." C “pleonexia” [pleh ah neks ee ah] - “greediness, covetousness.” C Lit. “every form of greediness or covetousness.” a. What the brother wanted could be settled by the courts. 1) The Old Testament gave clear teaching regarding the inheritance of property. (Deut. 21:15-17; Num. 27:1-11; 36:7-9). 2) The circumstances of the dispute are not given, and are not important to the lesson Jesus wanted to stress. -

The Parables of Jesus Is That We Know the Punchline to the Stories (I.E

Sponsored by ENROLL occ.edu/admissions ONLINE COURSES occ.edu/online GIVE occ.edu/donate SESSION 1 -One of the problems with studying the parables of Jesus is that we know the punchline to the stories (i.e. we know how they end). -In this lesson we tell three stories outside of the Gospels to help us prepare for the study of the parables of Jesus. Three stories: # 1: Story of the Jewish tailor—there is such a thing as an enigmatic ending! Story leaves you wanting more! # 2: Story of the needy family with student in the signature group, “Impact Brass and Singers.” Story of the bad guy being the good guy! # 3: Story of the broken car and helping female faculty member by biker. Story of wrong perceptions and leaving open-ended. -Enigma, bad guys doing well, and wrong perceptions and open-ended are all characteristics of Jesus’ parables. SESSION 2 Resources -Kenneth Bailey says that Jesus was a “metaphoric theologian.” Well, if that’s true we are probably going to need some help understanding him because metaphor, symbolism and analogies are not always easy to interpret. Resources (from most significant to lesser significant): 1) Klyne Snodgrass, Stories with Intent. 2) Kenneth Bailey, Through Peasant Eyes, Poet and Peasant, and Jesus through Middle Easter Eyes. 3) Gary Burge, Jesus the Storyteller. 4) Craig Blomberg, Interpreting the Parables. 5) Craig Blomberg, Preaching the Parables. 6) Roy Clements, A Sting in the Tale. 7) C.H. Dodd, The Parables of the Kingdom. 8) William Herzog, The Parables as Subversive Speech. -

Sheol by Saying “Lowest” Hell

Jesus went there as well, “For thou wilt ever use a personal name. He may say, not leave my soul in hell; neither wilt thou “there once was a king,” or “there once FROM THE BEGINNING suffer thine Holy One to see corruption” was a man” but He never uses names. In www.creationinstruction.org (402) 756-5121 [email protected] (Ps 16:10). Yet at the same time, the this story Jesus names a real person named wicked receive punishment there: “For a Lazarus. He also names Abraham, a real, 1770 S Overland Ave – Juniata NE 68955 fire is kindled in mine anger, and shall living spirit. The “rich man” goes to the Oct-Dec 2006 VOL. 45 burn unto the lowest hell” (Deut 32:22). same place upon death that Lazarus does, Note, that this verse suggests different however, it seems that this hadee is levels of sheol by saying “lowest” hell. separated into two sections. People cannot Greetings in Christ! Our new website is up and going. It is the same address just with (See also Num 16:30; Ps 9:17 and Matt pass from the lower portion to the upper improved functionality. Please visit the forum section where you can communicate with 11:23). At the same time, the same place is portion. The lower portion, where the rich others and put any feedback you have regarding this newsletter or any other topic you desire. considered to be a place of reward for the man is, is still a place of torment since he You can win a free DVD by posting a comment. -

26 Sunday in Ordinary Time – Year C Luke 16:19-31 Yet

26th Sunday in ordinary Time – year C Luke 16:19-31 Yet another very unusual parable, which Jesus shares with the Pharisees (and us!)… What exactly does Jesus seek to reveal? Jesus contrasts great comfort with great distress: a rich man who dressed and ate well and a poor man who did not. Jesus contrasts, more deeply, self-satisfaction with yearning. Jesus contrasts a closed heart with an open heart. The two men die. The poor man dies and is immediately taken to the bosom of Abraham, the abode of bliss. The rich man dies and is simply buried, and from there, the netherworld, cries. As far as I can tell, this is not primarily a parable about heaven and hell. Jesus is speaking to the Pharisees, in relation to their beliefs (which, regarding heaven and hell, are unclear). The netherworld – Hades in Greek, Sheol in Hebrew – is not hell (which is Gehenna). The netherworld is • the abode of the dead • the unknown region • the invisible world of departed souls It is to this netherworld that Jesus, when He dies, descends to free the just. [Jesus does not descend into hell, where there is no room or receptivity.] There are other signs that the rich man is not in hell: 1. The love he exhibits for his relatives. There is no love in hell. 2. The original Greek terms that are translated “torture” or “torment”. • do not suggest the pain of definitive separation but the different pain of testing, purification, correction • have a connotation of sorrow or internal pain 3. -

Rich Man and Lazarus March 14, 2021

A Mission Congregation of the ELCA Trinity Evangelical Lutheran Church P. O. Box 64 - 8520 Oakes Rd - Pitsburg, Ohio 45358 Rich Man and Lazarus March 14, 2021 • Prelude “Remember; Jesus Messiah; At the Cross” Darrell Fryman • Office of the Acolyte and Ringing of the Bell • Welcome Pr Mel ∗ CONFESSION AND FORGIVENESS All may make the sign of the cross, the sign marked at baptism, as the presiding minister begins. P: We confess our sins before God and one another. Pause for silence and reflection. P: God of mercy, C: Jesus was faithful even in the face of death, yet we so often fail you in day to day living. Our commitment is shaky, our promises are unreliable, and our actions are questionable. We quit when discipleship becomes difficult and complain that we don’t get enough credit. Forgive us our neglect of your mission and our lukewarm devotion and wake us up to the urgency of your gospel. P: God is gracious and pardons all our shortcomings. May the giver of life forgive us our sins and restore us to the joy of discipleship and service, for the sake of Jesus our faithful Lord. C: Amen. ∗ Please stand if able March 14, 2021 • Please be seated Page 2 of 15 ∗ HYMN OF PRAISE “When Peace, Like A River” LBW 346 Verses 1 & 4 Only ∗ APOSTOLIC GREETING P: The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with you all. C: And also with you. ∗ PRAYER OF THE DAY P: Let us pray… Merciful God, you care deeply for those who are in need. -

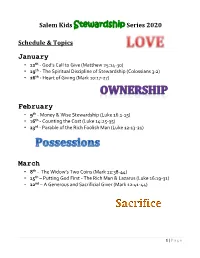

Sunday School Lesson (Mark 10:17-27) Stewardship for Kids Ministry-To-Children.Com/Heart-Of-Giving-Lesson

Salem Kids Stewardship Series 2020 Schedule & Topics January • 12th - God’s Call to Give (Matthew 25:14-30) • 19th - The Spiritual Discipline of Stewardship (Colossians 3:2) • 26th - Heart of Giving (Mark 10:17-27) February • 9th - Money & Wise Stewardship (Luke 16:1-15) • 16th - Counting the Cost (Luke 14:25-35) • 23rd - Parable of the Rich Foolish Man (Luke 12:13-21) March • 8th - The Widow’s Two Coins (Mark 12:38-44) • 15th – Putting God First - The Rich Man & Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31) • 22nd – A Generous and Sacrificial Giver (Mark 12:41-44) 1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Lesson: God’s Call to Give (Matthew 25:14-30) Stewardship for Kids ministry-to-children.com/stewardship-lesson-1 Scripture: Matthew 25:14-30 Supplies: Pencils, paper, yellow circles of construction paper Lesson Opening: What is Stewardship? Ask: Has anyone ever heard the word “Steward” before? What do you think it means? (A steward is someone who takes care of another person’s property.) Ask: What does it mean to be responsible for something? Ask: What are some things that you are responsible for? Ask: Did you know that God has made each of us stewards? We are all stewards over the things that God entrusts to us. Say: We’ll hear a parable, or story, about 3 servants who were responsible for their master’s money. Pray that God would open their hearts to His Word today and that He would stir our hearts to be good stewards of His creation and that we would give back to Him with thankful hearts. -

What Happens After Death According to the Hymns in the LSB

What Happens after Death According to the Hymns in the LSB What follows is meant to be proactive, meaning that I intend it to be a guide for those who write hymn texts and for those who select hymns for publication in the future, rather than a critique of texts that have been written and published in the past. I have wanted to do a study like this ever since seminary days when I heard professor Arthur Carl Piepkorn say that the laity in our Church get their theology primarily from hymns. That struck me as true then, and I think it is still true today. If it is true, then what follows should be of interest to anyone who writes hymns texts, translates them from other languages, edits earlier translations, selects hymn texts for publication, or reviews them for doctrinal correctness, as well as to everyone who uses them in worship, mediation or prayer. In my own case, before I got to the seminary, I believed that at death believers go immediately to heaven in the full sense of the word, a belief held by many of our lay people and many pastors. This is not surprising since the Book of Concord, which we believe is a correct and authoritative interpretation of the Sacred Scriptures, states: “We grant that the angels pray for us . We also grant that the saints in heaven (in coelis, im Himmel) pray for the church in general, as they prayed for the church while they were on earth. But neither a command nor a promise nor an example can be shown from Scripture for the invocation of the saints; from this it follows that consciences cannot be sure about such invocation.” (My italics. -

Outcasts (5): Blessed Are the Poor (Luke 6:20-26) I

Outcasts (5): Blessed Are the Poor (Luke 6:20-26) I. Introduction A. We continue today with “Outcasts: Meeting People Jesus Met in Luke” 1. Luke has a definite interest in people on the-outside-looking-in a. His birth narrative tells of shepherds, the mistrusted drifter-gypsies b. Later she shows Jesus touched lepers, ultimate of aunclean outcasts c. He mentions tax collectors more than Matthew and Mark combined 2. The outcast we will look at today from Luke’s gospel is the poor a. Jesus first sermon in Luke was a text on the poor (Luke 4:18-19) b. John asks from prison if Jesus is really Messiah (Luke 7:22-23) c. Jesus is asked about handwashing & ritual purity (Luke 11:39-40) d. Jesus proclaims his own solidarity with the poor (Luke 9:58) e. Jesus equates the kingdom with giving to poor (Luke 12:32-34) 3. Jesus had quite a lot to say about the poor in Luke (see more later) a. Were some of those text just a little bit unfamiliar to us? Why? b. What first pops into our head when we think of helping the poor c. Did you think Bernie Sanders and “Liberal Democratic Socialism?” 1) Political Test: The difference between socialism and capitalism 2) Socialism is man exploiting man. Capitalism is other way around 3) Jesus doesn’t care about our politics; he wants us to care about poor B. Our “outcast” Jesus encounters will be quite different this morning 1. Jesus doesn’t run into a poor person; he stood and teach (Luke 6:17) a.