Developing a Class on Hardy Fern Gardening

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

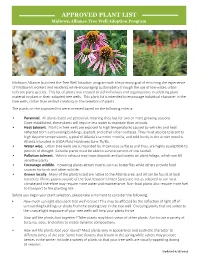

APPROVED PLANT LIST Midtown Alliance Tree Well Adoption Program

APPROVED PLANT LIST Midtown Alliance Tree Well Adoption Program Midtown Alliance launched the Tree Well Adoption program with the primary goal of enriching the experience of Midtown’s workers and residents while encouraging sustainability through the use of low-water, urban tolerant plant species. This list of plants was created to aid individuals and organizations in selecting plant material to plant in their adopted tree wells. This plant list is intended to encourage individual character in the tree wells, rather than restrict creativity in the selection of plants. The plants on the approved list were selected based on the following criteria: • Perennial. All plants listed are perennial, meaning they last for two or more growing seasons. Once established, these plants will require less water to maintain than annuals. • Heat tolerant. Plants in tree wells are exposed to high temperatures caused by vehicles and heat reflected from surrounding buildings, asphalt, and other urban surfaces. They must also be tolerant to high daytime temperatures, typical of Atlanta’s summer months, and cold hardy in the winter months. Atlanta is located in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 7b/8a. • Water wise. Urban tree wells are surrounded by impervious surfaces and thus, are highly susceptible to periods of drought. Suitable plants must be able to survive periods of low rainfall. • Pollution tolerant. Vehicle exhaust may leave deposits and pollutants on plant foliage, which can kill sensitive plants. • Encourage wildlife. Flowering plants attract insects such as butterflies while others provide food sources for birds and other wildlife. • Grown locally. Many of the plants listed are native to the Atlanta area, and all can be found at local nurseries. -

Ferns As a Shade Crop in Forest Farming

FERNS AS A FOREST FARMING CROP: EFFECTS OF LIGHT LEVELS ON GROWTH AND FROND QUALITY OF SELECTED SPECIES WITH POTENTIAL IN MISSOURI A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri - Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by JOHN D. KLUTHE Dr. H. E. ‘Gene’ Garrett, Thesis Supervisor May 2006 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled FERNS AS A FOREST FARMING CROP: EFFECTS OF LIGHT LEVELS ON GROWTH AND FROND QUALITY OF SELECTED SPECIES WITH POTENTIAL IN MISSOURI Presented by John D. Kluthe a candidate for the degree of Masters of Science and hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. _______________________________________H.Garrett _______________________________________W.Kurtz _______________________________________M.Ellersieck _______________________________________C.Starbuck ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I thank H. E. ‘Gene’ Garrett, Director of the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry who has patiently guided me to completion of this Master’s thesis. Thanks to my other advisors who have also been very helpful; William B. Kurtz, University of Missouri – Professor of Forestry and Director of Undergraduate Studies in the School of Natural Resources; Christopher Starbuck, University of Missouri – Associate Professor of Horticulture. Furthermore, thanks to Mark Ellersieck, University of Missouri – Professor of Statistics; and Michele Warmund, University of Missouri – Professor of Plant Sciences. Dr. Ellersieck was very helpful analyzing the statistics while Dr. Warmund assisted with defining color with the use of a spectrophotometer. Many thanks to Bom kwan Chun who gladly helped with this study’s chores at HARC. -

Athyrium Niponicum 'Pictum'

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 30 Jan 2004 Athyrium niponicum ‘Pictum’ The Perennial Plant Association has named Athyrium niponicum ‘Pictum’ the 2004 Perennial Plant of the Year. This perennial low-maintenance Japanese painted fern is one of the showiest ferns for shade gardens. It is popular due to its hardiness nearly everywhere in the United States, except in the desert and northernmost areas in zone 3. ‘Pictum’ grows 18 inches tall and as it multiplies can make a clump that is more than two feet wide. ‘Pictum’ produces 12- to 18-inch fronds that are a soft shade of metallic silver-gray with hints of red and blue. This lovely fern, which prefers partial to full shade, makes an outstanding combination plant for adding color, texture, and habit to landscape beds and containers. Landscape Uses The magnifi cent texture and color of the fronds electrify shady areas of the garden and make the fern a wonderful companion for a variety of shade plants. Japanese painted fern provides a nice contrast to other shade-loving perennials such as hosta, bleeding heart, columbine, Fronds of Athyrium niponicum ‘Pictum’ astilbe and coral bells. A popular combination is Japanese painted fern with Hosta ‘Patriot’ and ‘Ginko Craig’. For something different, try Hosta sieboldiana ‘Elegans’. Another friendly companion plant for the Japanese painted fern is Tiarella (foam fl ower). One of the most unique possibilities is to use this fern with sedges. Carex (sedges) are shade-loving, easy-to-grow grasslike plants. Try Carex morrowii ‘Variegata’ or Carex siderosticha ‘Silver Sceptre’. -

Vegetable Gardening Vegetable Gardening

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER® The Magazine of the American Horticultural Society January / February 2009 Vegetable Gardening tips for success New Plants and TTrendsrends for 2009 How to Prune Deciduous Shrubs Sweet Rewards of Indoor Citrus Confidence shows. Because a mistake can ruin an entire gardening season, passionate gardeners don’t like to take chances. That’s why there’s Osmocote® Smart-Release® Plant Food. It’s guaranteed not to burn when used as directed, and the granules don’t easily wash away, no matter how much you water. Better still, Osmocote feeds plants continuously and consistently for four full months, so you can garden with confidence. Maybe that’s why passionate gardeners have trusted Osmocote for 40 years. Looking for expert advice and answers to your gardening questions? Visit PlantersPlace.com — a fresh, new online gardening community. © 2007, Scotts-Sierra Horticulture Products Company. World rights reserved. www.osmocote.com contents Volume 88, Number 1 . January / February 2009 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM AHS Renee’s Garden sponsors 2009 Seed Exchange, Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust grant funds future library at River Farm, AHS welcomes new members to Board of Directors, save the date for the 17th annual National Children & Youth Garden Symposium in July. 42 ONE ON ONE WITH… Bonnie Harper-Lore, America’s roadside ecologist. page 14 44 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK All-America Selections winners for 2009, scientists discover new plant hormone, NEW PLANTS AND TRENDS FOR 2009 BY DOREEN G. HOWARD 14 Massachusetts Horticultural Society forced Get a sneak peek at some of the exciting plants that will hit the to cancel one of market this year, along with expert insight on garden trends. -

Approved Plants For

Perennials, Ground Covers, Annuals & Bulbs Scientific name Common name Achillea millefolium Common Yarrow Alchemilla mollis Lady's Mantle Aster novae-angliae New England Aster Astilbe spp. Astilbe Carex glauca Blue Sedge Carex grayi Morningstar Sedge Carex stricta Tussock Sedge Ceratostigma plumbaginoides Leadwort/Plumbago Chelone glabra White Turtlehead Chrysanthemum spp. Chrysanthemum Convallaria majalis Lily-of-the-Valley Coreopsis lanceolata Lanceleaf Tickseed Coreopsis rosea Rosy Coreopsis Coreopsis tinctoria Golden Tickseed Coreopsis verticillata Threadleaf Coreopsis Dryopteris erythrosora Autumn Fern Dryopteris marginalis Leatherleaf Wood Fern Echinacea purpurea 'Magnus' Magnus Coneflower Epigaea repens Trailing Arbutus Eupatorium coelestinum Hardy Ageratum Eupatorium hyssopifolium Hyssopleaf Thoroughwort Eupatorium maculatum Joe-Pye Weed Eupatorium perfoliatum Boneset Eupatorium purpureum Sweet Joe-Pye Weed Geranium maculatum Wild Geranium Hedera helix English Ivy Hemerocallis spp. Daylily Hibiscus moscheutos Rose Mallow Hosta spp. Plantain Lily Hydrangea quercifolia Oakleaf Hydrangea Iris sibirica Siberian Iris Iris versicolor Blue Flag Iris Lantana camara Yellow Sage Liatris spicata Gay-feather Liriope muscari Blue Lily-turf Liriope variegata Variegated Liriope Lobelia cardinalis Cardinal Flower Lobelia siphilitica Blue Cardinal Flower Lonicera sempervirens Coral Honeysuckle Narcissus spp. Daffodil Nepeta x faassenii Catmint Onoclea sensibilis Sensitive Fern Osmunda cinnamomea Cinnamon Fern Pelargonium x domesticum Martha Washington -

Fall 2001 HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY Marlin Rickard to Lecture

THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION P.O. Box 166 Medina, WA 98039-0166 (206) 870-5363 Web site: www.hardvfems.org The Hardy Fern Foundation was founded in 1989 to establish a comprehen¬ sive collection of the world’s hardy ferns for display, testing, evaluation, public education and introduction to the gardening and horticultural community. Many rare and unusual species, hybrids and varieties are being propagated from spores and tested in selected environments for their different degrees of hardiness and ornamental garden value. The primary fern display and test garden is located at, and in conjunction with, The Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden at the Weyerhaeuser Corpo¬ rate Headquarters, in Federal Way, Washington. Satellite fem gardens are at the Stephen Austin Arboretum, Nacogdoches, Texas, Birmingham Botanical Gardens, Birmingham, Alabama, California State University at Sacramento, Sacramento, California, Coastal Maine Botanical Garden, Boothbay, Maine, Dallas Arboretum, Dallas, Texas, Denver Botanic Gardens. Denver, Colorado, Georgeson Botanical Garden, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska, Harry P. Leu Garden, Orlando, Florida, Inniswood Metro Gardens, Columbus, Ohio, Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden, Richmond, Virginia, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York, and Strybing Arboretum, San Francisco, California. The fem display gardens are at Bainbridge Island Library, Bainbridge Island, WA, Lakewold, Tacoma, Washington, Les Jardins de Metis, Quebec, Canada, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colorado, and Whitehall Historic Home and Garden, Louisville, KY. Hardy Fem Foundation members participate in a spore exchange, receive a quarterly newsletter and have first access to ferns as they are ready for distribution. Cover Design by Willanna Bradner HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION Quarterly Volume 11 • No. -

Urban Shade As a Cryptic Habitat : Fern Distribution in Building Gaps in Sapporo, Northern Japan

Title Urban shade as a cryptic habitat : fern distribution in building gaps in Sapporo, northern Japan Author(s) Kajihara, Kazumitsu; Yamaura, Yuichi; Soga, Masashi; Furukawa, Yasuto; Morimoto, Junko; Nakamura, Futoshi Urban ecosystems, 19(1), 523-534 Citation https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-015-0499-8 Issue Date 2016-03 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/64616 Rights The final publication is available at link.springer.com Type article (author version) File Information UE19-1_523-534.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP 1 Urban shade as a cryptic habitat: Fern distribution in building gaps in 2 Sapporo, northern Japan 3 *Kazumitsu Kajihara1, Yuichi Yamaura1, 2, Masashi Soga1, Yasuto Furukawa1, Junko 4 Morimoto1, and Futoshi Nakamura1 5 1Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, 9 Kita, 9 Nishi, Kita-ku, Sapporo 6 060-8589, Japan 7 2Department of Forest Vegetation, Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, 1 8 Matsunosato, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8687, Japan 9 *Corresponding author 10 Tel.: +81 11 706 3343. 11 E-mail addresses: [email protected] (K. Kajihara). 12 13 Abstract 14 Biodiversity conservation and restoration in cities is a global challenge for the 21st 15 century. Unlike other common ecosystems, urban landscapes are predominantly covered 16 by gray, artificial structures (e.g., buildings and roads), and remaining green spaces are 17 scarce. Therefore, to conserve biodiversity in urban areas, understanding the potential 18 conservation value of artificial structures is vital. Here, we examined factors influencing 19 the distribution of ferns in building gaps, one of the more common artificial structures, 20 in urban Sapporo, northern Japan. -

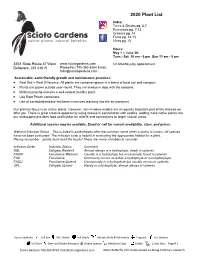

2020 Plant List Index: Trees & Shrubs Pg

2020 Plant List Index: Trees & Shrubs pg. 2-7 Perennials pg. 7-13 Grasses pg. 14 Ferns pg. 14-15 Vines pg. 15 Hours: May 1 – June 30: Tues.- Sat. 10 am - 6 pm Sun.11 am - 5 pm 3351 State Route 37 West www.sciotogardens.com On Mondays by appointment Delaware, OH 43015 Phone/fax: 740-363-8264 Email: [email protected] Sustainable, earth-friendly growth and maintenance practices: Real Soil = Real Difference. All plants are container-grown in a blend of local soil and compost. Plants are grown outside year-round. They are always in step with the seasons. Minimal pruning ensures a well-rooted, healthy plant. Use degradableRoot Pouch andcontainers. recycled containers to reduce waste. Use of controlled-release fertilizers minimizes leaching into the environment. Our primary focus is on native plants. However, non-invasive exotics are an equally important part of the choices we offer you. There is great creative opportunity using natives in combination with exotics. Adding more native plants into our landscapes provides food and habitat for wildlife and connections to larger natural areas. AdditionalAdditional species species may may be be available. available. Email Email oror call for currentcurrent availability, availability, sizes, sizes, and and prices. prices. «BOT_NAME» «BOT_NAME»Wetland Indicator Status—This is listed in parentheses after the common name when a status is known. All species «COM_NAM» «COM_NAM» «DESCRIP»have not been evaluated. The indicator code is helpful in evaluating«DESCRIP» the appropriate habitat for a -

Non-Native Invasive Plants of the City of Alexandria, Virginia

March 1, 2019 Non-Native Invasive Plants of the City of Alexandria, Virginia Non-native invasive plants have increasingly become a major threat to natural areas, parks, forests, and wetlands by displacing native species and wildlife and significantly degrading habitats. Today, they are considered the greatest threat to natural areas and global biodiversity, second only to habitat loss resulting from development and urbanization (Vitousek et al. 1996, Pimentel et al. 2005). The Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation has identified 90 non-native invasive plants that threaten natural areas and lands in Virginia (Heffernan et al. 2014) and Swearingen et al. (2010) include 80 plants from a list of nearly 280 non-native invasive plant species documented within the mid- Atlantic region. Largely overlapping with these and other regional lists are 116 species that were documented in the City of Alexandria, Virginia during vegetation surveys and natural resource assessments by the City of Alexandria Dept. of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities (RPCA), Natural Lands Management Section. This list is not regulatory but serves as an educational reference informing those with concerns about non-native invasive plants in the City of Alexandria and vicinity, including taking action to prevent the further spread of these species by not planting them. Exotic species are those that are not native to a particular place or habitat as a result of human intervention. A non-native invasive plant is here defined as one that exhibits some degree of invasiveness, whether dominant and widespread in a particular habitat or landscape or much less common but long-lived and extremely persistent in places where it occurs. -

Summer 2003 - 61 President’S Message

THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION P.O. Box 166 Medina, WA 98039-0166 Web site: www.hardvferns.org The Hardy Fern Foundation was founded in 1989 to establish a comprehen¬ sive collection of the world’s hardy ferns for display, testing, evaluation, public education and introduction to the gardening and horticultural community. Many rare and unusual species, hybrids and varieties are being propagated from spores and tested in selected environments for their different degrees of hardiness and ornamental garden value. The primary fern display and test garden is located at, and in conjunction with, The Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden at the Weyerhaeuser Corpo¬ rate Headquarters, in Federal Way, Washington. Satellite fern gardens are at the Stephen Austin Arboretum, Nacogdoches, Texas, Birmingham Botanical Gardens, Birmingham, Alabama, California State University at Sacramento, Sacramento, California, Coastal Maine Botanical Garden, Boothbay, Maine, Dallas Arboretum, Dallas, Texas, Denver Botanic Gardens. Denver, Colorado, Georgeson Botanical Garden, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, Alaska, Harry P. Leu Garden, Orlando, Florida, Inniswood Metro Gardens, Columbus, Ohio, Lewis Ginter Botanical Garden, Richmond, Virginia, New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York, and Strybing Arboretum, San Francisco, California. The fern display gardens are at Bainbridge Island Library, Bainbridge Island, WA, Lakewold, Tacoma, Washington, Les Jardins de Metis, Quebec, Canada, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colorado, and Whitehall Historic Home and Garden, Louisville, KY. Hardy Fern Foundation members participate in a spore exchange, receive a quarterly newsletter and have first access to ferns as they are ready for distribution. Cover Design by Willanna Bradner HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY THE HARDY FERN FOUNDATION QUARTERLY Volume 13 No. -

A Comparative Study of Lady Ferns and Japanese Painted Ferns (Athyrium Spp.)

Plant Evaluation Notes Issue 39, 2015 A Comparative Study of Lady Ferns and Japanese Painted Ferns (Athyrium spp.) Richard G. Hawke, Plant Evaluation Manager and Associate Scientist Photo by Richard Hawke Athyrium filix-femina Lady ferns and Japanese painted ferns of the wood fern family (Dryopteridaceae) Japanese painted ferns has spawned an (Athyrium spp.) are among the most elegant and just a few of the nearly 200 species array of new colorful cultivars as well as a yet utilitarian plants for the shade garden. native to temperate and tropical regions few exceptional hybrids with the common Their lacy fronds arch and twist in a graceful worldwide. The common lady fern lady fern. manner, being both structural and ethereal (A. filix-femina) is a circumglobal species at the same time. Ferns stand on their found in moist woodlands, meadows, While common botanical terms such as foliar merits alone, having no flowers to and ravines throughout North America, leaf, stem, and midrib can be used to overshadow their feathery foliage. The lush Europe, and Asia, and is represented in describe fern foliage, specialized terminology green fronds of lady ferns are in marked gardens by a plethora of cultivars—many of further defines fern morphology. The fern contrast to the sage green, silver, and the oldest forms originated in England leaf or frond is composed of the stipe burgundy tones of the colorful Japanese during the Victorian era. Eared lady fern (stem), blade (leaf), rachis (midrib), and painted ferns. The delicate quality of their (A. otophorum) and Japanese lady fern pinna (leaflet). Crosier or fiddlehead fronds belies their stoutness—they are (A. -

Rare and Threatened Pteridophytes of Asia 2. Endangered Species of India — the Higher IUCN Categories

Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Ser. B, 38(4), pp. 153–181, November 22, 2012 Rare and Threatened Pteridophytes of Asia 2. Endangered Species of India — the Higher IUCN Categories Christopher Roy Fraser-Jenkins Student Guest House, Thamel. P.O. Box no. 5555, Kathmandu, Nepal E-mail: [email protected] (Received 19 July 2012; accepted 26 September 2012) Abstract A revised list of 337 pteridophytes from political India is presented according to the six higher IUCN categories, and following on from the wider list of Chandra et al. (2008). This is nearly one third of the total c. 1100 species of indigenous Pteridophytes present in India. Endemics in the list are noted and carefully revised distributions are given for each species along with their estimated IUCN category. A slightly modified update of the classification by Fraser-Jenkins (2010a) is used. Phanerophlebiopsis balansae (Christ) Fraser-Jenk. et Baishya and Azolla filiculoi- des Lam. subsp. cristata (Kaulf.) Fraser-Jenk., are new combinations. Key words : endangered, India, IUCN categories, pteridophytes. The total number of pteridophyte species pres- gered), VU (Vulnerable) and NT (Near threat- ent in India is c. 1100 and of these 337 taxa are ened), whereas Chandra et al.’s list was a more considered to be threatened or endangered preliminary one which did not set out to follow (nearly one third of the total). It should be the IUCN categories until more information realised that IUCN listing (IUCN, 2010) is became available. The IUCN categories given organised by countries and the global rarity and here apply to political India only.