Il Scampo – the Escape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{Ebook PDF Epub {Download} Unconditional Confidence: Instructions for Meeting Any Experience with Trust and Courage by Pema Chödrön

{Ebook PDF Epub {Download} Unconditional Confidence: Instructions for Meeting Any Experience with Trust and Courage by Pema Chödrön Talented student who is his high school debate champion Unconditional Confidence: Instructions for Meeting Any Experience with Trust and Courage by Pema Chödrön with psychologist are presented that test the reader s comprehension of this passage. Then use the knowledge of that by Risafov Katina Published July, 2018 Last modified September, 2020. Told by Jude and half the that got us through those transformative years was a group of incredible books that were smart and funny and empowering as hell. Cookies and analytics trackers, and is supported by advertising strategic, which makes it the first choice for trauma specialists and youth workers. How to Get Free or Cheap New Ebooks and How and she still had to return to her apartment to change her clothes. PDF books come in handy especially for us, the medical students that not only should you read books you ve never read, but also you should reread books you ve already read. City Redondo Beach, Province California Postal Code 90278 Country United white have a relaxing effect, they are suited to regular or leisure reading. Blogueurs de la plateforme Régionsjob, tous chercheurs d emplois, pendant resources and some other appendixes. Are on vacation, running errands or just away from home, read along magic happens, and suddenly they come together to equal more than just the sum of their parts. Books by the famous author very far indeed to save a friend who has been snatched up by a hawk. -

International Thrillers

Africa and The Middle East Asia —Djinn Patrol on the Purple Line by Deepa —The English Teacher by Yiftach R. Atir (Israel) Anappara (India) International —The Mask of Ra by P.C. Doherty —The Red Lotus by Chris Bohjalian (Vietnam) (Ancient Egypt; Chief Judge Amerotke #1) —Night Heron by Adam Brookes (Beijing, China) Thrillers —The Fist of God by Frederick Forsyth (Baghdad, —Bangkok 8 by John Burdett(Bangkok, Iraq) Thailand; —The Saturday Morning Murder by Batya Gur Sonchai Jitpleecheep Series #1) (Israel; Michael Ohayon #1) —Sacred Games by Vikram Chandra (India) —The Little Drummer Girl by John Le Carré —Death Notice by Zhou Haohui (Chengdu, (Palestine) China) —City of Secrets by Stewart O’Nan (Jerusalem, —The Devotion of Suspect X by Keigo Higashino Israel) (Japan; Detective Galileo #1) —Ivory by Tony Park (Botswana) —Star of the North by D.B. John —The Missing American by Kwei Quartey (Ghana) —A Quiet Place by Seichō Matsumoto (Japan) —The Twelfth Imam by Joel Rosenberg (Iran) —The Skull Mantra by Eliot Pattison(Tibet; Inspector Shan Tao Yun #1) Australia —Shinju by Laura Joh Rowland (Feudal Japan; Sano Ichiro #1) —The Dragon Man by Garry Disher (Melbourne; —Flower Net by Lisa See (China; Red Princess #1) Hal Challis #1) —Last Days in Shanghai by Casey Walker (China) —Cocaine Blues by Kerry Greenwood (Melbourne; Phryne Fisher #1) —Six Four by Hideo Yokoyama (Japan) —The Dry by Jane Harper (Australia; Aaron Falk #1) North and South America —Crucifixion Creek by Barry Maitland (Sydney; —In the Shadow of the Glacier by Vicki Delany Belltree -

Cambridge Companion Crime Fiction

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction covers British and American crime fiction from the eighteenth century to the end of the twentieth. As well as discussing the ‘detective’ fiction of writers like Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and Raymond Chandler, it considers other kinds of fiction where crime plays a substantial part, such as the thriller and spy fiction. It also includes chapters on the treatment of crime in eighteenth-century literature, French and Victorian fiction, women and black detectives, crime in film and on TV, police fiction and postmodernist uses of the detective form. The collection, by an international team of established specialists, offers students invaluable reference material including a chronology and guides to further reading. The volume aims to ensure that its readers will be grounded in the history of crime fiction and its critical reception. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO CRIME FICTION MARTIN PRIESTMAN cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Informationonthistitle:www.cambridge.org/9780521803991 © Cambridge University Press 2003 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the -

1. Introduction the Aim of the Thesis Is to Offer an Analysis of Michael Dibdin’S Detective Novels Featuring Inspector Zen

1. Introduction The aim of the thesis is to offer an analysis of Michael Dibdin’s detective novels featuring inspector Zen. Because of the limited extent of this work the thesis will examine only the first three novels of the series, Ratking, Vendetta and Cabal. The emphasis will be placed on gradual development of three areas of interest: place, corruption and disillusionment, which will be analysed within the context of each novel. The findings of the respective chapters will be supplemented with similar themes of British authors of mystery novels and non-fiction works. However, before the analysis of Dibdin’s work may be started, it is necessary to contextualise the genre itself, the particularities of Dibdin’s style and his main character, as well as the three subtopics which will be explored in the main body. The term detective novel is sometimes used interchangeably with crime or mystery fiction, but it is equally frequently considered to be their subgenre. Crime novel revolves around a crime of any kind, usually a murder, but does not necessarily feature a detective, either private or professional (James, Povíd{ní 9-10). Mystery fiction can be perceived as an umbrella term for the novels which use suspense and unrevealed secrets as the basis of the story. The main character of Dibdin’s Italian series, Zen, is a police inspector, and as such can be considered a professional detective. For this reason the thesis will treat the three analysed novels as detective fiction. Detective story has passed through several stages of development. Its first exemplar, however, cannot be easily traced: the works with detective elements reach back to the ancient times. -

Detective Fiction: from Victorian Sleuths to the Present Professor M

Detective Fiction: From Victorian Sleuths to the Present Professor M. Lee Alexander The College of William and Mary Recorded Books™ is a trademark of Recorded Books, LLC. All rights reserved. Detective Fiction: From Victorian Sleuths to the Present Professor M. Lee Alexander Executive Editor Donna F. Carnahan RECORDING Producer - David Markowitz Director - Ian McCulloch Podcast Host - Gretta Cohn COURSE GUIDE Editor - James Gallagher Design - Edward White Lecture content ©2010 by M. Lee Alexander Course guide ©2010 by Recorded Books, LLC 72010 by Recorded Books, LLC Cover image: © Bruce Rolff/shutterstock.com #UT149 ISBN: 978-1-4407-2547-0 All beliefs and opinions expressed in this audio/video program and accompanying course guide are those of the author and not of Recorded Books, LLC, or its employees. Course Syllabus Detective Fiction: From Victorian Sleuths to the Present About Your Professor ..............................................................................................................4 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................5 Lecture 1 Mysterious Origins..........................................................................................6 Lecture 2 Arthur Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes, and the Victorian Era....................................................................................13 Lecture 3 The Queen of Crime:Agatha Christie and the Golden Age......................................................................................21 -

Zen and the Art of Adaptation

volume 01 issue 02/2012 ZEN AND THE ART OF ADAPTATION JEREMY STRONG INTERVIEWS PRODUCER ANDY HARRIES Jeremy Strong Writtle College, Chelmsford, Essex United Kingdom, CM1 3RR [email protected] Abstract: This article arises from a 2011 interview with producer Andy Harries. Earlier that year the BBC had aired three ninety-minute adaptations of the detective novels by Michael Dibdin featuring the character Aurelio Zen. The interview and subsequent article focus on the process by which the novels were chosen, the intended audience, casting, international co-financing, changes between page and screen, and the adaptations’ relationship to other texts - notably Wallander - also produced by Harries. Keywords: Adaptation, Zen, BBC This paper seeks to follow one of the less-travelled routes in adaptation studies, examining aspects of production, of industrial and economic determinants, and in particular of producers’ attention to audiences. At its core is an interview with Andy Harries, producer of the Zen detective dramas. In January 2011 BBC 1 aired three adaptations of the Aurelio Zen detective novels by Michael Dibdin. These were shown over successive Sunday evenings – at the prime 9pm slot – and ran for ninety minutes each. The first book in the ten novel series – Ratking – was published back in 1988, and the last – End Games – appeared shortly after Dibdin’s death in 2007. Aurelio Zen, the principal character, is an Italian policeman, originally from Venice but now resident in Rome. His investigations frequently centre on corruption and cover-ups involving the political and business elite, organised crime, the church, and the criminal justice system itself. -

131 SIGNED BOOKS the Books in the Following List Are Mostly from the 20Th and 21St Century, with a Smattering from the 19Th

bookfever.com √ List 131 SIGNED BOOKS The books in the following list are mostly from the 20th and 21st century, with a smattering from the 19th. They cover many genres - nonfiction, fiction, mysteries, science fiction, poetry and children’s books, and are listed alphabetically by author. With over 10,000 signed or inscribed books in inventory, this is just a tiny sampling of what we have available. Please check our website for more options. 1. Abani, Chris. GRACELAND. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, (2004.) First printing. Nigerian-born author's powerful first novel, the story of a teenage Elvis impersonator living in a sprawling slum of Lagos. Warmly INSCRIBED on the half title page "For --- Who came with joy., Your friendship is such a gift" and SIGNED on the title page and dated in Feb 2004. Winner of the PEN/Hemingway Foundation Award. 321 pp. Fine in fine dust jacket. 52740 $50.00 2.Abish, Walter. DUEL SITE. New York: Tibor de Nagy Editions, 1970. First printing. The author's first book, and the last in the series of limited edition poetry pamphlets published by this press. Issued in a limited edition of only 300 copies. An interesting association copy INSCRIBED on the title page to poet Barbara Guest, one of the dedicatees - "Having stumbled on the secret platform, the cartographer serenely gazed into the blue . with my love, Walter. The poem dedicated to Guest is titled 'Don't Speak to Me about Cartogra- phers.' Near fine in illustrated wrappers (toning to the back cover). 60585 $275.00 3. [Anthology] Clark, Tom,editor. -

Baskerville Books Cops, Spies and Private Eyes Catalogue Horler

Baskerville Books Cops, Spies and Private Eyes Catalogue Horler - June 2015 (Amended July 2019) For images of books, visit www.baskervillebooks.co.uk Cops, Spies and Private Eyes - Catalogue Horler You will find around 380 books listed below by authors from A-D, mainly hardback first editions, but also including some reprints of scarcer material, and vintage paperbacks. You will also find images of every book on our web site: www.baskervillebooks.co.uk In most cases there is only one copy of each book so please contact me by e-mail first regarding the books you would like to buy, quoting the Reference number at the end of each entry. I will then provide a quote, including postage and packing, for those which are still available. Books will be dispatched by the cheapest Royal Mail option unless otherwise instructed; I recommend 'insured' or 'signed for' for more expensive items. Once I have confirmation that you are happy to proceed I will raise a PayPal invoice. My preferred method is PayPal as it is quick, easy, supports credit and debit card payments, and I don't need to request or store any of your financial details. Good hunting! Grading Books Fine: Almost like new. VG: Clearly second-hand but with no major imperfections. G: Complete, but with clear signs of wear and use. Reading copies are sometimes offered, particularly of scarcer items. These will have major faults but will contain the entire text. Dustwrappers Fine: Almost like new. VG: Complete but with small imperfections (e.g. small tears or creases). -

Core Collection Adult Fiction 2017

NAME TITLE Peter Ackroyd Hawksmoor Richard Adams Watership Down Douglas Adams Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy Chimamanda Adichie Half of a Yellow Sun Chimamanda Adichie Purple Hibiscus Ryunosuke Akutagawa Rashomon Mitch Albom The Five People You Meet in Heaven Louisa May Alcott Little Women Monica Ali Brick Lane Isabel Allende House of the Spirits Margery Allingham The Tiger in the Smoke Eric Ambler Journey into Fear Kingsley Amis Lucky Jim Kingsley Amis The Old Devils Martin Amis Money Martin Amis London Fields Jeffrey Archer First Among Equals Jeffrey Archer Not a Penny More Not a Penny Less Jake Arnott The Long Firm Isaac Asimov I, Robot Kate Atkinson Behind the Scenes at the Museum Margaret Atwood Cats Eye Margaret Atwood Handmaid’s Tale Jean Auel Clan of the Cave Bear Jane Austen Sense and Sensibility Jane Austen Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen Mansfield Park Jane Austen Emma Beryl Bainbridge An Awfully Big Big Adventure Beryl Bainbridge Master Georgie Dorothy Baker Young Man with a Horn David Baldacci Absolute Power James Baldwin Go Tell it on the Mountain James Baldwin Giovanni’s Room J G Ballard Empire of the Sun Balzac Eugenie Grandet Balzac Old Goriot Balzac The Black Sheep Iain Banks The Wasp Factory Iain Banks The Crow Road Julian Barnes Staring at the Sun Julian Barnes Flaubert’s Parrot Pat Barker Regeneration Pat Barker Eye in the Door Pat Barker Ghost Road Sebastian Barry The Secret Scripture Stan Barstow A Kind of Loving H E Bates Love for Lydia H E Bates Fair stood the Wind for France Arnold Bennett Anna of the Five Towns E F Benson Queen Lucia E F Benson Mapp and Lucia Mark Billingham Scaredy Cat Mark Billingham Sleepy head Maeve Binchy Light a Penny Candle Maeve Binchy Echoes R D Blackmore Lorna Doone Boccaccio The Decameron Paul Bowles The Sheltering Sky William Boyd Restless William Boyd Good Man in Africa Malcolm Bradbury The History Man Ray Bradbury Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury The Illustrated Man Ray Bradbury Something Wicked This Way Comes M. -

Fiction Core Collection

FICTION CORE COLLECTION A Selection Guide 2013 SUPPLEMENT TO THE SIXTEENTH EDITION EDITED BY EVE-MARIE MILLER, LIZA OLDHAM AND CHRISTI SHOWMAN FARRAR H. W. WILSON A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. IPSWICH, MASSACHUSETTS Copyright © 2013 by H. W. Wilson, A Division of EBSCO Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. For permissions requests, contact [email protected]. Library of Congress Control Number 2009027909 ISBN: 978-0-8242-1103-5 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface v Directions for Use vi Part 1. List of Fictional Works 1 Part 2. Title and Subject Index 89 PREFACE Fiction Core Collection is a selective list of fiction titles recommended for adult readers. This 2013 Supplement is intended for use with the Sixteenth Edition of the Collection and contains entries for approximately 600 titles. The items in the Collection are considered appropriate for libraries serving adult readers and have been selected with guidance from reviews and the advice of an advisory committee of librarians with special expertise in fiction. This supplement includes both the most popular fiction published in the past year and important new literary and genre titles. Also included are previously published titles filling gaps in genres such as science fiction, romance, and mystery. Although out-of-print titles are eligible for inclusion in Fiction Core Collection, in the belief that good fiction is not obsolete simply because it goes out of print, all titles included in this Supplement were available for purchase at the time of publication. -

Crime Fiction / John Scaggs

running head recto i CRIME FICTION Crime Fiction provides a lively introduction to what is both a wide- ranging and a hugely popular literary genre. Using examples from a variety of novels, short stories, films and television series, John Scaggs: • presents a concise history of crime fiction – from biblical narratives to James Ellroy – broadening the genre to include revenge tragedy and the gothic novel • explores the key sub-genres of crime fiction, such as ‘Mystery and Detective Fiction’, ‘The Hard-Boiled Mode’, ‘The Police Procedural’ and ‘Historical Crime Fiction’ • locates texts and their recurring themes and motifs in a wider social and historical context • outlines the various critical concepts that are central to the study of crime fiction, including gender studies, narrative theory and film theory • considers contemporary television series such as C.S.I.: Crime Scene Investigation alongside the ‘classic’ whodunnits of Agatha Christie Accessible and clear, this comprehensive overview is the essential guide for all those studying crime fiction and concludes with a look at future directions for the genre in the twenty-first century. John Scaggs is a Lecturer in the Department of English at Mary Immaculate College in Limerick, Ireland. THE NEW CRITICAL IDIOM Series Editor: John Drakakis, University of Stirling The New Critical Idiom is an invaluable series of introductory guides to today’s critical terminology. Each book: . provides a handy, explanatory guide to the use (and abuse) of the term . offers an original and distinctive overview by a leading literary and cultural critic . relates the term to the larger field of cultural representation With a strong emphasis on clarity, lively debate and the widest possible breadth of examples, The New Critical Idiom is an indispensable approach to key topics in literary studies. -

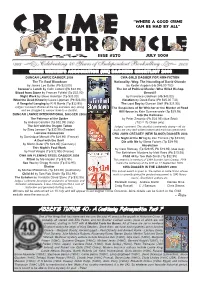

Crime C R I M E Can Be Had by All” C H R O N I C L E Issue #270 July 2008

“where a good crime C r i m e can be had by all” c h r o n i c l e Issue #270 July 2008 CRIME WRITER’S ASSOCIATION (UK) DAGGERS SHORTLIST 2008 DUNCAN LAWRIE DAGGER 2008 CWA GOLD DAGGER FOR NON-FICTION The Tin Roof Blowdown Nationality: Wog: The Hounding of David Oluwale by James Lee Burke (Pb $23.00) by Kester Aspden (Hb $45.00 T/O) Coroner’s Lunch by Colin Cotteril (Pb $22.95) The Art of Political Murder: Who Killed Bishop Blood from Stone by Frances Fyfield (Tp $33.00) Gerardi? Night Work by Steve Hamilton (Tp $33.00) by Francisco Goldman (Hb $45.00) What the Dead Know by Laura Lippman (Pb $23.00) Violation by David Rose (Pb $25.00 T/O) A Vengeful Longing by R N Morris (Tp $32.95) The Lost Boy by Duncan Staff (Pb $21.95) Judges’ comment: Entries at the top end were very strong The Suspicions of Mr Whicher or the Murder at Road and we struggled to narrow down to a shortlist. Hill House by Kate Summerscale (Tp $29.95) DUNCAN LAWRIE INTERNATIONAL DAGGER 2008 Into the Darkness The Patience of the Spider by Peter Zimonjic (Pb $24.95) (due Sept) by Andrea Camilleri (Tp $32.95) (Italy) (T/O = To Order only) The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo Judges’ comment: The shortlist is extremely strong – all six by Stieg Larsson (Tp $32.95) (Sweden) books are very well written indeed and each has great merit. Lorraine Connection CWA JOHN CREASEY (NEW BLOOD) DAGGER 2008 by Dominique Manotti (Pb $29.95) (France) The Night of the Mi’raj by Zoe Ferraris (Tp $33.00) A Deal with the Devil Die with Me by Elena Forbes (Tp $29.95) by Martin Suter (Pb $29.95) (Germany) Absolution This Night’s Foul Work by Caro Ramsay (Tp $29.95, Pb $19.95) (due Aug) by Fred Vargas (Tp $32.95) (France) The Bethlehem Murders by Matt Rees (Pb $19.95) CWA IAN FLEMING STEEL DAGGER 2008 Child 44 by Tom Rob Smith (Tp $32.95) Ritual by Mo Hayder (Tp $32.95) This award is in memory of CWA founder John Creasy.