The Real Story of John Carteret Pilkington Writen by Himself

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 K - Z Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society K - Z July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

THE LONDON Gfaz^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237

THE LONDON GfAZ^TTE, JULY 5, 1904. 4237 ; '.' "• Y . ' '-Downing,Street. Charles, Earl of-Leitrim. '-'--•'. ' •' July 5, 1904. jreorge, Earl of Lucan. The KING has been pleased to approve of the Somerset Richard, Earl of Belmore. appointment of Hilgrpye Clement Nicolle, Esq. Tames Francis, Earl of Bandon. (Local Auditor, Hong Kong), to be Treasurer of Henry James, Earl Castle Stewart. the Island of Ceylon. Richard Walter John, Earl of Donoughmore. Valentine Augustus, Earl of Kenmare. • William Henry Edmond de Vere Sheaffe, 'Earl of Limericks : i William Frederick, Earl-of Claricarty. ''" ' Archibald Brabazon'Sparrow/Earl of Gosford. Lawrence, Earl of Rosse. '• -' • . ELECTION <OF A REPRESENTATIVE PEER Sidney James Ellis, Earl of Normanton. FOR IRELAND. - Henry North, -Earl of Sheffield. Francis Charles, Earl of Kilmorey. Crown and Hanaper Office, Windham Thomas, Earl of Dunraven and Mount- '1st July, 1904. Earl. In pursuance of an Act passed in the fortieth William, Earl of Listowel. year of the reign of His Majesty King George William Brabazon Lindesay, Earl of Norbury. the Third, entitled " An Act to regulate the mode Uchtef John Mark, Earl- of Ranfurly. " by which the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Jenico William Joseph, Viscount Gormanston. " the Commons, to serve ia the Parliament of the Henry Edmund, Viscount Mountgarret. " United Kingdom, on the part of Ireland, shall be Victor Albert George, Viscount Grandison. n summoned and returned to the said Parliament," Harold Arthur, Viscount Dillon. I do hereby-give Notice, that Writs bearing teste Aldred Frederick George Beresford, Viscount this day, have issued for electing a Temporal Peer Lumley. of Ireland, to succeed to the vacancy made by the James Alfred, Viscount Charlemont. -

The London Gazette, May 10, 1910. 3251

THE LONDON GAZETTE, MAY 10, 1910. 3251 At the Court at Saint James's, the 7th day of Marquess of Londonderry. May, 1910. Lord Steward. PRESENT, Earl of Derby. Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery. The KING'S Most Excellent Majesty in Council. Earl of Chesterfield. "IS Majesty being this day present in Council Earl of Kintore. was pleased to make the following' Earl of Rosebery. Declaration:— Earl Waldegrave. " My Lords and Gentlemen— Earl Carrington. My heart is too full for Me to address you Earl of Halsbury. to-day in more than a few. words. It is My Earl of Plymouth. sorrowful duty to announce to you the death of Lord Walter Gordon-Lennox. My dearly loved Father the King. In this Lord Chamberlain. irreparable loss which has so suddenly fallen Viscount Cross. upon Me and upon the whole Empire, I am Viscount Knutsford. comforted by the feeling that I have the Viscount Morley of Blackburn. sympathy of My future subjects, who will Lord Arthur Hill. mourn with Me for their beloved Sovereign, Lord Bishop of London. whose own happiness was found in sharing and Lord Denman. promoting theirs. I have lost not only a Lord Belper. Father's love, but the affectionate and intimate Lord Sandhurst. relations of a dear friend and adviser. No less Lord Revelstoke. confident am I in the universal loving sympathy Lord Ashbourne. which is assured to My dearest Mother in her Lord Macnaghten. overwhelming grief. Lord Ashcombe. Standing here a little more than nine years Lord Burghclere. ago, Our beloved King declared that as long as Lord James of Hereford. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

W. A. Campbell, Prominent Laurel Hill Citizen Dies

OCCG£ - ^ ■ VOLUME XXX NUMBER 98 ^ Fall/Winler 2008 ^rom thefiCes ofthe HN'orthwest 'Flhrida ^Herita^e Museum, VaCparaiso, Source: IN'ewspaper cCipping, ^oC 10 -S^o. 47. IN'o name orcCate shown W. A. Campbell, Prominent Laurel Hill Citizen Dies Family Tree Gives Direct Descent From Old Scotland The Deceased Was At One Time Walton County Commissioner And Was In Good Shape Mr. W. A. Campbell, better known to his intimate friends as "Uncle Bud," passed away quietly at his home in the Magnolia settlement four miles to the west of Laurel Hill, early yesterday (Wednesday) morning. The deceased was 79 years old and one of the first settlers in this section of the State, his great-grandparents being direct descendents from Scotland to America over two hundred years ago. (A biography of the family tree is given below.) The Campbells The following news story is copied from the Pensacola Gazette of December 10, 1842: "There now resides in Walton County, about 75 miles from this (Pensacola place, a man and wife whose united ages is 229 years. The old gentleman's name is Daniel Campbell. He was united to his present wife 94 years ago, on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. He emigrated to this country several years before the Revolution, and was about 50 years old when the war begun. There were no neutrals then and as Mr. Campbell left his native country in consequence of the political troubles of 1745, he was prepared to take part vdth the Colonists against the House of Hanover. He served through nearly the entire Revolutionary War, but although very poor he has not been able to avail himself of the county, or rather of the just remuneration which the pension laws have provided for the survivors of that glorious epoch, because before the passage of the Act of 1832 he was by extreme old age and mental infirmity rendered incapable of making the declaration required by the law. -

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

The London-Gazette, October 30, 1885. 4981

THE LONDON-GAZETTE, OCTOBER 30, 1885. 4981 Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders (Ross-shire 3rd Forfar {Dundee Highland"), James Farmer Buffs, tie Duke of Albany's). Walter Andrew Anderson, Gent., to be Lieutenant. Dated Fraser, Gent., to be Lieutenant. Dated 31st 3lsi October, 1885. October, 1885. 1st Volunteer Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment, 5lh Battalion, the Rifle Brigade (the Prince Lieutenant John Sampson Furley to be Captain. Consort's Own), Lieutenant George Dalbiac Dated 31st October, 1885. Luard resigns his Commission.- Dated 31st ]st Volunteer Batfalion, the Buffs (East Kent . October, J885. Ret/imtni), Captain Edward Foord-Kelcey 1th Battalion, the Rifle Brigade (the Prince resigns his Commission. Dated 31st October, Condon's Own), David Edward McCall, Gent., 1885. to tfe [Lieutenant. Dated 31st October, 1885. 18th Lancashire ( Liverpool Irish), Samuel William 3rd,.Battalion, the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, Henry Richards, Gent., to be Lieutenant. Dated 31st Hjugo Patrick de Burgh, Gent., to be Lieu- October, 1885. tenant. Dated 31st October, 1885. 21st Lancashire, Major Richard Filkington is 5th Battalion, the Eoyal Dublin. Fusiliers, Ewing granted the honorary rank of Lieutenant- Wrigley Grimshaw, Gent., to be Lieutenant. Colonel. Dated 16th October, 1885. Dated 31st October, 1885. Sth {S.W.) Middlesex, Captain George Tyrrell YEOMANRY CAVALRY. resigns his Commission ; also is granted the Oxfordshire, The Honourable Edward Alexander honorary rank of Major ; and is permitted to Stonor to be Lieutenant. Dated 31st October, continue to wear the uniform of the Corps on 1885. his retirement. Dated 31st Octoher, 1885. VOLUNTEER CORPS. 15th Middlesex (the Customs and the Dochs), Lieutenant Henry William Pollock resigns his ARTILLERY. -

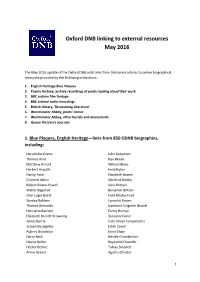

Oxford DNB Linking to External Resources May 2016

Oxford DNB linking to external resources May 2016 The May 2016 update of the Oxford DNB adds links from Dictionary articles to online biographical resources provided by the following institutions: 1. English Heritage Blue Plaques 2. Poetry Archive, archive recordings of poets reading aloud their work 3. BBC archive film footage 4. BBC archive radio recordings 5. British Library, ‘Discovering Literature’ 6. Westminster Abbey, poets’ corner 7. Westminster Abbey, other burials and monuments 8. Queen Victoria’s Journals 1. Blue Plaques, English Heritage—links from 850 ODNB biographies, including: Harold Abrahams John Betjeman Thomas Arne Nye Bevan Matthew Arnold William Blake Herbert Asquith Enid Blyton Nancy Astor Elizabeth Bowen Clement Attlee Winifred Holtby Robert Paden-Powell Vera Brittain Walter Bagehot Benjamin Britten John Logie Baird Ford Madox Ford Stanley Baldwin Lancelot Brown Thomas Barnardo Isambard Kingdom Brunel Henrietta Barnett Fanny Burney Elizabeth Barrett Browning Giovanni Canal James Barrie Cato Street Conspirators Joseph Bazalgette Edith Cavell Aubrey Beardsley Ernst Chain Harry Beck Neville Chamberlain Hilaire Belloc Raymond Chandler Hector Berlioz Tobias Smollett Annie Besant Agatha Christie 1 Winston Churchill Arthur Conan Doyle William Wilberforce John Constable Wells Coates Learie Constantine Wilkie Collins Noel Coward Ivy Compton-Burnett Thomas Daniel Charles Darwin Mohammed Jinnah Francisco de Miranda Amy Johnson Thomas de Quincey Celia Johnson Daniel Defoe Samuel Johnson Frederic Delius James Joyce Charles Dickens -

List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007

Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007 A - J Library and Information Services List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 A complete listing of all Fellows and Foreign Members since the foundation of the Society A - J July 2007 List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 - 2007 The list contains the name, dates of birth and death (where known), membership type and date of election for all Fellows of the Royal Society since 1660, including the most recently elected Fellows (details correct at July 2007) and provides a quick reference to around 8,000 Fellows. It is produced from the Sackler Archive Resource, a biographical database of Fellows of the Royal Society since its foundation in 1660. Generously funded by Dr Raymond R Sackler, Hon KBE, and Mrs Beverly Sackler, the Resource offers access to information on all Fellows of the Royal Society since the seventeenth century, from key characters in the evolution of science to fascinating lesser- known figures. In addition to the information presented in this list, records include details of a Fellow’s education, career, participation in the Royal Society and membership of other societies. Citations and proposers have been transcribed from election certificates and added to the online archive catalogue and digital images of the certificates have been attached to the catalogue records. This list is also available in electronic form via the Library pages of the Royal Society web site: www.royalsoc.ac.uk/library Contributions of biographical details on any Fellow would be most welcome. -

A History of Dunluce

1 (Reconstruction of Dunluce, as it may have looked circa 1620) A History of Dunluce by Hon, Hector McDonnell Castle Kenbane Councillor, Council of Finlaggan INTRODUCTION Dunluce castle is one of the most dramatic and romantic ruins in Ireland, with cliffs isolating the crag on which it stands from the mainland on all sides. It must therefore have been an ideal site for a defensive position from the earliest times, but as its entire top surface was intensively cleared, flattened and built over during the 16th and 17th centuries that the only surviving object from earlier times is a souterrain, a subterranean tunnel used for hiding both goods and people at many Irish sites during the 9th and 10th centuries. After the Normans arrived circa 1200 the land around Dunluce was developed as one of a string of manors which they established along the north Antrim coast, and by the early 16th century a family called MacQuillan held Dunluce as their chief fortress. They controlled a large part of north county Antrim until in the 1550s they were ousted by a Scottish clan, the MacDonnells, who had already established their control over the Glens of Antrim some time before. It was under the MacDonnells, led by their wonderfully named leader, Sorley Boy MacDonnell, (Sorley the Fair Haired) that Dunluce achieved prominence, and became an important centre of resistance to English expansion into Ulster. The MacDonnells were 2 particularly significant in this struggle because they brought in large numbers of Highland fighting men for any Irish chieftains who needed them, and Dunluce was one of the strongest fortresses held by a native family anywhere in Ireland. -

The Armorial Plaques in the Royal Salop Infirmary

Third Series Vol. VI part 1. ISSN 0010-003X No. 219 Price £12.00 Spring 2010 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume VI 2010 Part 1 Number 219 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor + John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A., M.PHIL., PH.D. Noel COX, LL.M., M.THEOL., PH.D., M.A., F.R.HIST.S. Andrew Hanham, B A., PH.D. Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam PLATE 4 Royal Shrewsbury Hospital, board room: four armorial plaques formerly in the Royal Salop Infirmary, showing the arms of treasurers of that institution. Top left (a), Richard Hill (1780). Top right (b), Sir Walter Corbet, Bart. (1895). Bottom left (c), the Earl of Plymouth (1928). Bottom right (d), General Sir Charles Grant (1941). See pages 27-32. THE ARMORIAL PLAQUES IN THE ROYAL SALOP INFIRMARY Janet Verasanso In the eighteenth century Shrewsbury, like most English towns, was crowded and unhealthy. 'Contagious', 'sweating' and 'putrid' fevers were rampant; death was ubiquitous, not only among the old and young but also among those in the prime of life.1 By the 1730s a number of socially conscious country gentlemen realised that the conditions in which the poor lived required an urgent solution.