The Fall of Edward Colston and the Rise of Inclusive Place-Based Leadership by Professor Richard Bolden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globe 140611

June 2011 INSIDE Who’s keeping an eye on College Green? The Memory Shed all our histories Music in Exile A taste of England Welcome to my home My favourite food… Kenya comes to Bristol Faith in the City Bristol City of Sanctuary Steering Committee Bristol City of Sanctuary Supporters CONTENTS June Burrough (Chair) Founder and Director, The Pierian Centre Co If your organisation would like to be Hotwells Primary School ng 3 Letter to Bristol ratula added this lists, please visit Imayla International Organisation tions Lorraine Ayensu Team Manager, Asylum Support and Refugee In - www.cityofsanctuary.org/bristol for Migration Inderjit Bhogal tegration Team, Bristol City Council Churches Council for Industry and Alistair Beattie Chief Executive, Faithnetsouthwest ACTA Community Theatre Social Responsibility 4 Editorial Caroline Beatty Co-ordinator, The Welcome Centre, Bristol African and Caribbean Chamber of John Wesley’s Chapel Mike Jempson to Bris Commerce and Enterprise Kalahari Moon to Refugee Rights l – Jo Benefield Bristol Defend Asylum Campaign African Initiatives Kenya Association in Bristol 5 A movement gaining ground Adam Cutler Bristol Central Libraries African Voices Forum Kingswood Methodist Church Stan Hazell Afrika Eye Malcom X Centre Mohammed Elsharif Secretary, Sudanese Association Amnesty International Bristol MDC Bristol Elinor Harris Area Manager, Refugee Action, Bristol p 6-7 The Memory Shed ro Group Methodist Church, South West ud to b Reverend Canon Tim Higgins The City Canon, Bristol Cathedral Eugene Byrne e Anglo-Iranian -

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Colston, Edward (1636–1721) Kenneth Morgan

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Colston, Edward (1636–1721) Kenneth Morgan • Published in print: 23 September 2004 • Published online: 23 September 2004 • This version: 9th July 2020 Colston, Edward (1636–1721), merchant, slave trader, and philanthropist, was born on 2 November 1636 in Temple Street, Bristol, the eldest of probably eleven children (six boys and five girls are known) of William Colston (1608–1681), a merchant, and his wife, Sarah, née Batten (d. 1701). His father had served an apprenticeship with Richard Aldworth, one of the wealthiest Bristol merchants of the early Stuart period, and had prospered as a merchant. A royalist and an alderman, William Colston was removed from his office by order of parliament in 1645 after Prince Rupert surrendered the city to the roundhead forces. Until that point Edward Colston had been brought up in Bristol and probably at Winterbourne, south Gloucestershire, where his father had an estate. The Colston family moved to London during the English civil war. Little is known about Edward Colston's education, though it is possible that he was a private pupil at Christ's Hospital. In 1654 he was apprenticed to the London Mercers' Company for eight years. By 1672 he was shipping goods from London, and the following year he was enrolled in the Mercers' Company. He soon built up a lucrative mercantile business, trading with Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Africa. From the 1670s several of Colston’s immediate family members became involved in the Royal African Company, and Edward became a member himself on 26 March 1680. The Royal African Company was a chartered joint-stock Company based in London. -

Oriel College Record

Oriel College Record 2020 Oriel College Record 2020 A portrait of Saint John Henry Newman by Walter William Ouless Contents COLLEGE RECORD FEATURES The Provost, Fellows, Lecturers 6 Commemoration of Benefactors, Provost’s Notes 13 Sermon preached by the Treasurer 86 Treasurer’s Notes 19 The Canonisation of Chaplain’s Notes 22 John Henry Newman 90 Chapel Services 24 ‘Observing Narrowly’ – Preachers at Evensong 25 The Eighteenth Century World Development Director’s Notes 27 of Revd Gilbert White 92 Junior Common Room 28 How Does a Historian Start Middle Common Room 30 a New Book? She Goes Cycling! 95 New Members 2019-2020 32 Eugene Lee-Hamilton Prize 2020 100 Academic Record 2019-2020 40 Degrees and Examination Results 40 BOOK REVIEWS Awards and Prizes 48 Gonzalo Rodriguez-Pereyra, Leibniz: Graduate Scholars 48 Discourse on Metaphysics 104 Sports and Other Achievements 49 Robert Wainwright, Early Reformation College Library 51 Covenant Theology: English Outreach 53 Reception of Swiss Reformed Oriel Alumni Advisory Committee 55 Thought, 1520-1555 106 CLUBS, SOCIETIES NEWS AND ACTIVITIES Honours and Awards 110 Chapel Music 60 Fellows’ and Lecturers’ News 111 College Sports 63 Orielenses’ News 114 Tortoise Club 78 Obituaries 116 Oriel Women’s Network 80 Other Deaths notified since Oriel Alumni Golf 82 August 2019 135 DONORS TO ORIEL Provost’s Court 138 Raleigh Society 138 1326 Society 141 Tortoise Club Donors 143 Donors to Oriel During the Year 145 Diary 154 Notes 156 College Record 6 Oriel College Record 2020 VISITOR Her Majesty the Queen -

Sites of Memory of Atlantic Slavery in European Towns with an Excursus on the Caribbean Ulrike Schmieder1

Cuadernos Inter.c.a.mbio sobre Centroamérica y el Caribe Vol. 15, No. 1, abril-setiembre, 2018, ISSN: 1659-0139 Sites of Memory of Atlantic Slavery in European Towns with an Excursus on the Caribbean Ulrike Schmieder1 Abstract Recepción: 7 de agosto de 2017/ Aceptación: 4 de diciembre de 2017 For a long time, the impact of Atlantic slavery on European societies was discussed in academic circles, but it was no part of national, regional and local histories. In the last three decades this has changed, at different rhythms in the former metropolises. The 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in France (1998) and the 200th anniversary of the prohibition of the slave trade in Great Britain (2007) opened the debates to the broader public. Museums and memorials were established, but they coexist with monu- ments to slave traders as benefactors of their town. In Spain and Portugal the process to include the remembrance of slavery in local and national history is developing more slowly, as the impact of slave trade on Spanish and Portuguese urbanization and in- dustrialization is little known, and the legacies of recent fascist dictatorships are not yet overcome. This article focuses on sites of commemoration and silent traces of slavery. Keywords Memory; slave trade; slavery; European port towns; Caribbean Resumen Durante mucho tiempo, la influencia de la esclavitud atlántica sobre sociedades euro- peas fue debatida en círculos académicos, pero no fue parte de historias nacionales, regionales y locales. En las últimas tres décadas esto ha cambiado a diferentes ritmos en las antiguas metrópolis. El 150 aniversario de la abolición de la esclavitud en Francia (1998) y el bicentenario de la prohibición del tráfico de esclavizados en Gran Bretaña (2007) abrieron los debates a un público más amplio. -

SLAVERY & Abolition

Bristol Insight : Open Top Bus and Walking Tours We take your group on a fully guided open top bus journey – or walking tour – taking in the important sites in Bristol linked to transatlantic slavery and its abolition. Our Tour Guides offer an informative and interactive tour introducing the controversial and often contradictory parts of Bristol’s history. This includes the city’s links to the transatlantic slave trade and the significant men and women who were involved. This can be a fully independent tour or can be linked with pick-ups/drop-offs at other locations in this leaflet. Suitable for: Key Stage 2 and above . For more details phone: 0117 971 9279 TRANSATLANTIC Email: [email protected] Website: www.bristolinsight.co.uk (and click the link for ‘Private Hire’ on the right hand side) SLAVERY & St Mary Redcliffe: Workshop and Tour Explore Bristol’s maritime history in an interactive workshop and meet the city’s explorers and merchants. AboLITIoN In this workshop we introduce the wealthy 15th century shipowner and Lord Mayor of Bristol William Canynges MP and explorer John Cabot who sailed to North America in 1497 in The Matthew. IN bRISToL We also consider the controversial merchant Edward Colston, who was both Deputy Governor of the Royal African Company, which traded in enslaved men, women and children but was also a generous benefactor within Bristol. Suitable for: Key Stage 2 and above . Tours, trips, workshops, For more details phone: 0117 231 0060 Email: sarah.yates@stmaryredcliffe.co.uk talks and exhibitions ©Emily Whitfield-Wicks Website: www.stmaryredcliffe.co.uk/education.html for schools and colleges Charity number 1134120 Each of the learning opportunities in this leaflet can be booked separately, but can also be combined for a longer visit and more enriching learning experience. -

Colston Revisited: Debating His Place in History and What His Legacy Means for Us Today

Colston revisited: debating his place in history and what his legacy means for us today. ▪ Stage One: Research, discussion & debate. ▪ Stage Two: Monday 21st September Period 3: Online Talk from Dr Madge Dresser. ▪ Stage Three: Should the school be renamed? Colston revisited: debating his place in history and what his legacy means for us today. • Dr Madge Dresser is Honorary Professor of History at the University of Bristol. • She has researched and written extensively on issues related to the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Bristol’s involvement with it. • Dr Dresser is very keen to help students at Colston’s School to debate and discuss issues associated with the slave trade and Edward Colston. She hopes to pose questions as much as answer them, but also to provide a structure for discussion and thinking on how History should be commemorated. She hopes to help you come to your own judgement on whether Colston’s School should continue to bear his name. Stage 1: Preparation Watch this 4 min. talk (start from 9.30 mins) by Dr Dresser from Dec. 2017. Take notes on Dr Dresser’s arguments ready for discussion. Listen to this 7 min. interview with Chris Patten, Chancellor of Oxford University, in Jan 2016 about the Cecil Rhodes statue at Oriel College. Take notes on the arguments ready for discussion. 1. Use your notes to write a short paragraph summing up the key points from the two clips. 2. Research definitions to these terms used in the talks: a) Silo-thinking. Task One b) Cancel Culture. Should we have a c) Civic belonging. -

Read the Latest 2019-2020 Edition Of

Fullerian 2019-20 Editor’s Note When I became editor of the Fullerian, the then headmaster pointed to all the copies of the previous magazines held in his study and said they reflected the very life and ethos of the school, and were held for posterity. Each year, three copies of the magazine are placed in the library and have, on occasion, been taken out and used as historical references. But what was going to happen this year when school trips, visits and musical events were cancelled from early March and then, finally, the school buildings themselves were closed on March 20th to the majority of students? The annual music report is shorter this year, with spring, summer and chamber concerts cancelled; there are no cricket or Sports Day reports and the number of visits and trips are very few. However, school did carry on for students and teachers in a different form. Teachers had to become accustomed to unfamiliar (to some teachers and a fair few students) technology, and students had to develop skills in independent learning, very rapidly, in very unusual circumstances. But from all of this emerged some outstanding work, and a large section of this Fullerian has been given over to celebrating the resilience and determination our students have shown to work in a very different manner from usual. In addition, you’ll find some evidence of extracurricular activities continuing, albeit on a modified basis, and some of our students taking advantage of Lockdown to pursue their own personal interests. Thank you to all those students, members of staff and parents who have helped provide contributions for this issue. -

The First Historians of Bristol: William Barrett and Samuel Seyer

THE FIRST HIS OF BRISTOL: WILLIAM BARRET'!·····., .... ,.··--·-·-- AND SAMUEL SEYER THE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS -THE FIRST HISTORIANS OF BRISTOL: Hon. General Editor: PETER HARRIS NORMA KNIGHT WILLIAM BARRETT Assistant General Editor: AND SAMUEL SEYER Editorial Advisor: JOSEPH BETTEY From the early Middle Ages successive chroniclers and antiquarians have The First Historians of Bristol: William Barrett and Samuel Seyer is the one calendared events and described incidents in the history of Bristol, but hundred and eighth pamphlet in this series.. not until the eighteenth century was there any attempt to write a Dr Joseph Bettey was Reader in Local History at the University of complete and accurate account of the history of the city, based on the Bristol and is the author of numerous books and articles on west-country documentary evidence. Writing in 1125, the monk, William of history. He has written several pamphlets in this series, most recently Malmesbury, described the commerce and shipping of the port of Bristol, St Augustine's Abbey, Bristol and The Royal Fort and Tyndall's Park: the and the struggle of St Wulstan to suppress the trade in slaves to Ireland. development of a Bristol landscape (nos. 88 and 92). Robert of Lewes, bishop of Bath from 1136 to 1166, chronicled the The publication of a pamphlet by the Bristol Branch of the Historical misdeeds of Bristolians in the army assembled at Bristol by Robert, Earl Association does not necessarily imply the Branch's approval of the of Gloucester, during the Civil War between the forces of Stephen and opinions expressed in it. -

Who Was Edward Colston and Why Was His Statue Pulled Down?’ by Dave Barnes

THE BAME EXPERIENCE Oasis Academy South Bank A Special Teacher Edition If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. 26th June 2020 – Desmond Tutu Issue 3 ‘Who was Edward Colston and why was his statue pulled down?’ By Dave Barnes How does this link to the Black Lives Matter movement? How does it link into Britain’s imperial history? On Monday the 8th of June 2020, the news across Britain was filled with images of a toppled statue in Bristol. The statue was of man called Edward Colston and protestors had pulled him from his plinth (the base upon which a statue stands), rolled him down the street and tipped him into the harbour. So, who was Edward Colston and why did protestors pull down his statue? Edward Colston lived from 1636- 1721 and was a slave trader. Colston was a board member and deputy governor of the Royal African Company. This was a company set up to take part in the Triangular Trade (that you learned about in year 7). In those roles, he helped to oversee the transportation into slavery of an estimated 84,000 Africans. Of them, it is be- lieved, around 19,000 died on slave ships during the infamous Middle Passage from the coast of Africa to plan- tations in the Americas. Those who survived the Middle Passage were forced to work on plantations growing sugar, cotton and tobacco for the rest of their lives in terrible conditions. Colston became very wealthy from trading human beings and gave some of his money to the city of Bristol. -

In Memory of Slave Traders Fathi Habashi

Laval University From the SelectedWorks of Fathi Habashi June 11, 2020 In Memory of Slave Traders Fathi Habashi Available at: https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/641/ In Memory of Slave Traders Introduction The protests all over the world when George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police in USA aroused the memory of slave traders1. London's mayor announced that more statues of imperialist figures could be removed from Britain's streets after protesters knocked down the monument to a slave trader in Bristol. By the 18th century, the slave trade became a major economic mainstay for such cities as Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow, engaged in the so-called "Triangular trade". The ships set out from Britain, loaded with trade goods which were exchanged on the West African shores for slaves captured by local rulers from deeper inland; the slaves were transported across the Atlantic, and were sold at considerable profit for labour in plantations. The ships were loaded with export crops and commodities, the products of slave labour, such as sugar and rum, and returned to Britain to sell the items. The triangle of slave trade African slaves European trading centers in West African coast 1 See https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/638/ Transporting the slaves Great Britain the major role in slavery. Other countries involved, beside Great Britain, were the Dutch, Portugal, France, and Denmark who built forts in Africa. Tribe leaders cooperated in this venture. Moslem traders were concentrated in Zanzibar and they traded in the east. Forts built in West Africa for handling of the slave trade British Slave Traders Colston Edward Colston (1636 –1721) was an English merchant and a Member of Parliament. -

Report on the Talk by Ms Kerry Mccarthy MP

Report on the Talk by Ms Kerry McCarthy MP Friday 18th September 2020 By Tara Arvind (Year 9) On the 18th of September, Labour MP Ms Kerry McCarthy talked to Year 9 pupils at Colston's School about Black Lives Matter. As an MP she represents Bristol East in Parliament. She was first elected in 2005 and has been elected to parliament five times. Ms McCarthy highlighted that Black Lives Matter is important for Bristol especially because of the city's connection with the slave trade, and the profit the city made from it. Firstly, she recalled that the Bristol Bus Boycott was about an 'outlawed discrimination on the grounds of race and colour'. She referred to Colston Hall, and how some bands didn't want to play there since the demonstration that led to the removal of Edward Colston's statue. She said that as society changes, parliament will need to make changes that reflect the state of society. She stated that changing the law doesn't necessarily mean anything and that it doesn't stop racism in itself but that you have to actually change people's hearts to be able to make a change. Ms McCarthy said that she agreed with BLM and she thought it was important. She thinks that people used racism as an opportunity to remove the statue of Edward Colston. However, she also feels that symbolic acts as such have more power than speeches and research. Even though it might be criminal damage, the Mayor couldn't condone the criminal damage because other people might think it is fine to choose to break the law. -

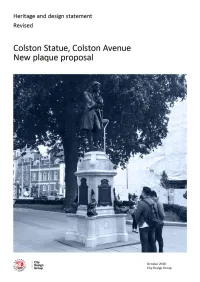

Attachment Colston Statue Design and Heritage Statement Redacted.Pdf.Pdf

Colston Statue October 2018 2 Heritage and design statement City Design Group Contents 1 Introduction Page no 4 Summary Planning policy context 2 Historic significance Page no 6 Edward Colston The statue Recent vandalism/artist interventions 3 The proposal Page no 10 Design process Statement of community involvement Design specification Assessment of harm October 2018 Colston Statue City Design Group Heritage and design statement 3 1 Introduction Summary Planning policy context In recent years Edward Colston has become a The statue of Edward Colston is a grade II listed recognised figurehead of the role Bristol merchants heritage asset. Consequently any works that have played in the enslavement and transportation of an impact on the special interest of the asset will Africans from the late 17th to 19th century. As require listed building consent in accordance with such the statue of Colston erected in 1895 has the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation become a target for the understandable public Areas) Act 1990. reaction to this distasteful past. The statue has Other relevant planning policies and guidance been the subject of several ‘art’ attacks such as his include: face being painted white, hand cuffs and a woollen National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF), ball and chain being added. One recent ‘attack’ Section 12 involved an ‘unauthorised’ plaque being added to Bristol Local Plan, policies BCS21 and DM31 the statues stone plinth. Although the sentiments of the plaque are understandable the content was In accordance with paragraph 128 of the NPPF factually inaccurate and the resin glue used to this document aims to provide a statement of apply the plaque has discoloured and damaged the significance for the asset and set the background stonework.