Information 117

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

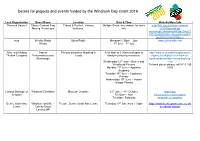

Details for Projects and Events Funded by the Windrush Day Grant 2019

Details for projects and events funded by the Windrush Day Grant 2019 Lead Organisation Event Name Location Date & Time Website/More info Thurrock Council Tilbury Carnival Flag Tilbury & Purfleet. Various Multiple Dates, see website for more http://tott.org.uk/tilbury-carnival- Making Workshops locations. info 2019-flag-making- workshops/?fbclid=IwAR3tpeSAxCV PIZYZpIZkiRo8Fn_FkvvjB8Js4dSrC ppuZN3C01HiOTObr_s. acta Weekly Radio Ujima Radio Mondays 1.30pm – 2pm www.ujimaradio.com Shows 3rd June – 1st July Alive and Kicking Drama Primary schools in Bradford & All to start at 9.30am and open to http://www.aliveandkickingtheatreco Theatre Company Performances and Leeds family/community members: mpany.co.uk/project/eh-kwik-eh- Workshops kwak-windrush-day-events-booking- Wednesday 12th June – Burley and now Woodhead Primary To book places please call 0113 295 Monday 17th June – Appleton 8190 Academy Tuesday 18th June – Copthorne Primary Wednesday 19th June – Horton Grange Primary London Borough of Windrush Exhibition Museum Croydon 12th June – 31st October https://jus- Croydon 10.30am – 4pm tickets.com/events/croydon- Tuesday - Saturday windrush-celebration/ Bernie Grant Arts Windrush and Me - Theatre, Bernie Grant Arts Centre Thursday 13th June from 7.30pm https://www.berniegrantcentre.co.uk/ Centre Talk by David see/david-lammy/ Lammy MP Details for projects and events funded by the Windrush Day Grant 2019 Bernie Grant Arts Pool of London Film Theatre, Bernie Grant Arts Centre Thursday 13th June from 7.00pm https://www.berniegrantcentre.co.uk/ Centre Screening see/film-pool-of-london-1951/ Bernie Grant Arts Rudeboy Film Theatre, Bernie Grant Arts Centre Saturday 15th & 21st June – 7pm https://www.berniegrantcentre.co.uk/ Centre Screening see/film-rudeboy/ London Borough of Windrush Highgate Library, Hornsey Library, 15th – 22nd June During library https://www.haringey.gov.uk/sites/ha Haringey Generation Displays St. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

Download Brochure

1 2 RELAX. YOU’VE FOUND THE PERFECT PLACE FOR FAMILY LIVING. St Mary’s Place offers a pair of stunning semi- The area has many fee paying schools including ACS detached homes in the highly desirable area of International in Cobham and the highly regarded Oatlands in Weybridge, Surrey. independent St George’s College in Weybridge. The area is also noted for its excellent state schools, Each home is luxuriously appointed and meticulously which include Manby Lodge Infants School, St James designed for modern family living. CE Primary School, Cleves School, Oatlands School Oatlands, less than a mile from the town centre of and Heathside School. Weybridge, is a sought after location named after the Concept Developments take great care to create Royal Tudor and Stuart, Oatlands Palace. designs that bring together the best of classic and St Mary’s Place is perfectly positioned for commuting contemporary style. Our dedicated interiors company, into London and ideal for enjoying riverside walks, Concept Interiors, bring a unique touch of luxury; rural adventures, and all that this family friendly town sophisticated and beautiful designs featuring on-trend has to offer. interiors, and a superb quality finish. inspire | design | build 3 WELCOME TO YOUR NEW HOME TIMELESS YET ON TREND. CLASSIC YET CONTEMPORARY. THE BEAUTY IS IN THE DETAIL AT ST. MARY’S ROAD. One thing you’ll notice with a Concept The lower ground floor forms the informal hub of Developments property, is the attention to detail. the family home comprising a grand open-plan The difference is evident from the moment you enter kitchen with a breakfast bar and family room through the private gates. -

Oatlands Palace

Oatlands Palace King Henry VIII owned lots of palaces near London. One of the most famous is Hampton Court Palace. Did you know that Henry had a palace in Elmbridge too? It was called Oatlands Palace and it was ENORMOUS! Most houses in Tudor times were built of wood or straw, but Oatlands palace was built of stone. Why do you think this was? Who lived in Oatlands Palace? Oatlands Palace was built by King Henry VIII almost 500 years ago! Henry loved building palaces and he used them to hold huge parties for his entire court. He had so many palaces he couldn’t use them all! So he started building them for other people. He built Oatlands palace for his wife, Anne of Cleves. Henry married lots of times. Do you know how many wives he had? Count the pictures below to find out! History Detectives So where is their enormous palace? Oatlands palace was built in Weybridge! It was knocked down hundreds of years ago, but bits of it can still be seen. Next time you are in Weybridge see if you can spot this gate. It used to be part of the palace! Henry did not live at Oatlands palace. He would travel to Oatlands when he wanted a break from busy London. Help Henry find his way tto Oatlands Palace! Patterns from the Palace One of the most exciting things we have found at Oatlands palace are floor tiles. They are covered in beautiful patterns. Here are some pictures of the tiles from Oatlands Palace. -

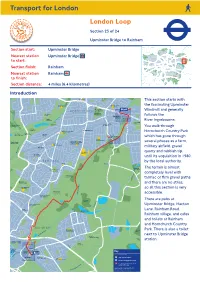

London Loop. Section 23 of 24

Transport for London. London Loop. Section 23 of 24. Upminster Bridge to Rainham. Section start: Upminster Bridge. Nearest station Upminster Bridge . to start: Section finish: Rainham. Nearest station Rainham . to finish: Section distance: 4 miles (6.4 kilometres). Introduction. This section starts with the fascinating Upminster Windmill and generally follows the River Ingrebourne. You walk through Hornchurch Country Park which has gone through several phases as a farm, military airfield, gravel quarry and rubbish tip, until its acquisition in 1980 by the local authority. The terrain is almost completely level with tarmac or firm gravel paths and there are no stiles, so all this section is very accessible. There are pubs at Upminster Bridge, Hacton Lane, Rainham Road, Rainham village, and cafes and toilets at Rainham and Hornchurch Country Park. There is also a toilet next to Upminster Bridge station. Directions. Leave Upminster Bridge station and turn right onto the busy Upminster Road. Go under the railway bridge and past The Windmill pub on the left. Cross lngrebourne River and then turn right into Bridge Avenue. To visit the Upminster Windmill continue along the main road for a short distance. The windmill is on the left. Did you know? Upminster Windmill was built in 1803 by a local farmer and continued to grind wheat and produce flour until 1934. The mill is only open on occasional weekends in spring and summer for guided tours, and funds are currently being raised to restore the mill to working order. Continue along Bridge Avenue to Brookdale Avenue on the left and opposite is Hornchurch Stadium. -

Guide to the Archive

Bernie Grant Trust Guide to the Bernie Grant Archive inspiration | innovation | inclusion Contents Compiled by Dr Lola Young OBE Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion . 4 Edited by Machel Bogues What’s in the Bernie Grant Archive? . 11 How it’s organised . 14 Index entries . 15 Tributes - 2000 . 16 What are Archives? . 17 Looking in the Archives . 17 Why Archives are Important . 18 What is the Value of the Bernie Grant Archive? . 18 How we set up the Bernie Grant Collection . 20 Thank you . 21 Related resources . 22 Useful terms . 24 About The Bernie Grant Trust . 26 Contacting the Bernie Grant Archive . 28 page | 3 Bernie Grant – the People’s Champion Born into a family of educationalists on London. The 4000 and overseas. He was 17 February 1944 in n 18 April 2000 people who attended a committed anti-racist Georgetown, Guyana, thousands of O the service at Alexandra activist who campaigned Bernie Grant was the people lined the streets Palace made this one of against apartheid South second of five children. of Haringey to follow the largest ever public Africa, against the A popular, sociable child the last journey of a tributes at a funeral of a victimisation of black at primary school, he charismatic political black person in Britain. people by the police won a scholarship to leader. Bernie Grant had in Britain and against St Stanislaus College, a been the Labour leader Bernie Grant gained racism in health services Jesuit boys’ secondary of Haringey Council a reputation for being and other public and school. Although he during the politically controversial because private institutions. -

News Update for London's Museums

@LondonMusDev E-update for London’s Museums – 09 November 2020 The 4 week long national lockdown began on Thursday 05 November, meaning museums and galleries should now be closed in line with government guidance until at least Wednesday 02 December. It has been announced that some heritage locations can still be visited if they are outside – provided current social distancing rules are observed. You can find further information about that on the Gov.uk website. You can get an overview of all of the new national restrictions on the gov.uk website. We strongly advise that you continue to follow the news and government announcements, as they happen, over the coming days and weeks. Last week the government announced further extensions to the furlough scheme, to March 2021. The government will extend furlough payments at the original 80%, up to a maximum of £2,500 per employee. Employers will only need to cover pension and National Insurance contributions during the month of November, but can top up the remaining 20% of their staff salaries if they wish. To be eligible for this extension, employees must have been on the payroll by 30 October 2020, but they do not need to have been furloughed before that date. Workers who were made redundant in advance of the planned end of the furlough scheme on 31 October can be rehired under the current furlough extension. The relevant section is 2.4 in the policy paper which can be found here. The government has also announced that businesses required to close in England due to local or national restrictions will be eligible for Business Grants of up to £3,000 per month, dependent on their rateable value. -

The New Museum School 2019-2020

The New Museum School 2019-2020 Kirsty Kerr, Archives and Digital Media Trainee at London Metropolitan Archives What is the New Museum School? The New Museum School addresses Culture&’s core objective to open up the arts and heritage sector through workforce initiatives and public programming. The School builds on our previous Skills for the Future programme, Strengthening Our Common Life, and is one of three new programmes in London Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. We have received further funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund to partner with Create Jobs to form a consortium of leading national, regional and local arts and heritage organisations to offer 34 traineeships over two years (2018 - 2020) that will address the skills gaps in the sector by focusing on digital and conservation skills. The traineeships will offer work-based training leading to an RQF Level 3 Diploma in Cultural Heritage to 34 trainees over two years with a tax-free bursary of equivalent to the London Living Wage, access to continuous professional development and to our peer-led alumni programme. Registered Charity 801111 Company Registered in England and Wales 2228599 Become a New Museum School host partner? Your organisation can be part of shaping a more diverse and vibrant museum, gallery and heritage sector for future generations. You can support and sign up to be a partner and host a trainee on the New Museum School and play your part in a positive step change for the sector. We know that you might need to advocate to your colleagues about this new initiative and your involvement so we have produced this document to give you a summary of what is involved and the type of outcomes you can expect from the programme. -

London and South East

London and South East nationaltrust.org.uk/groups 69 Previous page: Polesden Lacey, Surrey Pictured, this page: Ham House and Garden, Surrey; Basildon Park, Berkshire; kitchen circa 1905 at Polesden Lacey Opposite page: Chartwell, Kent; Petworth House and Park, West Sussex; Osterley Park and House, London From London living at New for 2017 Perfect for groups Top three tours Ham House on the banks Knole Polesden Lacey The Petworth experience of the River Thames Much has changed at Knole with One of the National Trust’s jewels Petworth House see page 108 to sweeping classical the opening of the new Brewhouse in the South East, Polesden Lacey has landscapes at Stowe, Café and shop, a restored formal gardens and an Edwardian rose Gatehouse Tower and the new garden. Formerly a walled kitchen elegant decay at Knole Conservation Studio. Some garden, its soft pastel-coloured roses The Churchills at Chartwell Nymans and Churchill at restored show rooms will reopen; are a particular highlight, and at their Chartwell see page 80 Chartwell – this region several others will be closed as the best in June. There are changing, themed restoration work continues. exhibits in the house throughout the year. offers year-round interest Your way from glorious gardens Polesden Lacey Nearby places to add to your visit are Basildon Park see page 75 to special walks. An intriguing story unfolds about Hatchlands Park and Box Hill. the life of Mrs Greville – her royal connections, her jet-set lifestyle and the lives of her servants who kept the Itinerary ideas house running like clockwork. -

Nonsuch Palace

MARTIN BIDDLE who excavated Nonsuch ONSUCH, ‘this which no equal has and its Banqueting House while still an N in Art or Fame’, was built by Henry undergraduate at Pembroke College, * Palace Nonsuch * VIII to celebrate the birth in 1537 of Cambridge, is now Emeritus Professor of Prince Edward, the longed-for heir to the Medieval Archaeology at Oxford and an English throne. Nine hundred feet of the Emeritus Fellow of Hertford College. His external walls of the palace were excavations and other investigations, all NONSUCH PALACE decorated in stucco with scenes from with his wife, the Danish archaeologist classical mythology and history, the Birthe Kjølbye-Biddle, include Winchester Gods and Goddesses, the Labours of (1961–71), the Anglo-Saxon church and Hercules, the Arts and Virtues, the Viking winter camp at Repton in The Material Culture heads of many of the Roman emperors, Derbyshire (1974–93), St Albans Abbey and Henry VIII himself looking on with and Cathedral Church (1978, 1982–4, the young Edward by his side. The 1991, 1994–5), the Tomb of Christ in of a Noble Restoration Household largest scheme of political propaganda the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (since ever created for the English crown, the 1989), and the Church on the Point at stuccoes were a mirror to show Edward Qasr Ibrim in Nubia (1989 and later). He the virtues and duties of a prince. is a Fellow of the British Academy. Edward visited Nonsuch only once as king and Mary sold it to the Earl of Martin Biddle Arundel. Nonsuch returned to the crown in 1592 and remained a royal house until 1670 when Charles II gave the palace and its park to his former mistress, Barbara Palmer, Duchess of Cleveland. -

January 2016 100 Minories - a Multi Period Excavation Next to London Wall, Guy Hunt L - P: Archaeology

CONTENTS Page Notices 2 Reviews and Articles 6 Books and Publications 16 Lectures 17 Affiliated Society Meetings 18 NOTICES Newsletter: Copy Date The copy deadline for the next Newsletter is 18 March 2016 (for the May 2016 issue). Please send items for inclusion by email preferably (as MS Word attachments) to: [email protected], or by surface mail to me, Richard Gilpin, Honorary Editor, LAMAS Newsletter, 84 Lock Chase, Blackheath, London SE3 9HA. It would be greatly appreciated if contributors could please ensure that any item sent by mail carries postage that is appropriate for the weight and size of the item. So much material has been submitted for this issue that some book reviews have had to be held over until the May 2016 issue. Marketing and Publicity Officer LAMAS is seeking a bright, efficient and enthusiastic person to become its Marketing and Publicity Officer. The Society has 650 members world-wide, including many archaeologists, historians and conservationists, and plays a leading role in the protection and preservation of London’s heritage. Through its publications, lectures and conferences LAMAS makes information on London’s past accessible to a wide audience. This interesting and varied job will involve the promotion and marketing of all of the Society's activities and especially publications, at events and online. The officer will be responsible to Council and make periodic reports to it. Experience of online marketing would be useful but is not necessary. Enthusiasm for London's archaeology and history is essential. The job is unpaid and honorary, as are those of all of the Society's officers. -

NICOLA GREEN Biography

www.facebook.com/nicolagreenstudio NICOLA GREEN @nicolagreenart @NicolaGreenArt Biography [email protected] +44 20 7263 6266 nicolagreen.com Nicola Green is a critically acclaimed artist and social historian. Green has established an international reputation for her ambitious projects that can change perceptions about identity and power; exploring themes of race, spirituality, religion, gender, and leadership. Green has gained unprecedented access to iconic figures from the worlds of religion, politics, and culture, including collaborations with Pope Francis, President Obama, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Dalai Lama. Driven by her belief in the power of the visual image to communicate important human stories, Nicola Green chooses to assume the role of ‘witness’ to momentous occasions taking place across the globe. Inspired by her own mixed-heritage children and multi-faith family, she creates and preserves religious, social, and cultural heritage for future generations. Recording these events as they happen, and investing many hours of academic and artistic research, Green builds and curates substantial archives. In 2015, Nicola Green, with ICF, co-founded the Phase I Diaspora Platform Programme, which would take emerging ethnic minority UK-based artists and curators to the 56th Venice Biennale to witness curator Okwui Enwezor ‘All The World’s Futures’ Biennale intervention, where he critically examined its entanglement with race, politics and power. Following these successes, Nicola Green co-founded and directed the Diaspora Pavilion, an exhibition at the 57th Venice Biennale, showcasing 22 artists from ethnic minority backgrounds, whose work dealt with the topic of Diaspora. The Diaspora Pavilion was created in an effort to highlight and address the lack of diversity in the arts sectors and was ac- companied by a 22-month long mentorship-based programme.