Economies of Relation 57

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiation in the Special Treatment of Developing Countries

SLICING UP THE DEVELOPING WORLD: DIFFERENTIATION IN THE SPECIAL TREATMENT OF DEVELOPING COUNTRIES Djalita Fialho The Science and Technology Foundation of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education of Portugal funded this PhD (SFRH/ BD/60826/2009). This dissertation is part of the Research Programme of CERES Research School for Resource Studies for Development © Djalita Nadine Fialho de Oliveira Ramos 2015 Cover design: graphic design by Érico Veríssimo All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. Printed in The Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-91478-32-1 Printed by: Ipskamp Drukkers B.V. Josink Maatweg 43 7545 PS Enschede The Netherlands Tel: 0031-(0)53 482 62 62 SLICING UP THE DEVELOPING WORLD: Differentiation in the special treatment of developing countries Het opdelen van de derde wereld: Differentiatie in de speciale behandeling van ontwikkelingslanden Thesis to obtain the degree of Doctor from the Erasmus University Rotterdam by command of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr Huibert A. P. Pols and in accordance with the decision of the Doctorate Board The public defence shall be held on 19 June at 16.00 hrs by Djalita Nadine Fialho de Oliveira Ramos born in Praia, Cape Verde Doctoral Committee Promotor Prof. dr. Peter A. G. van Bergeijk Other Members Prof. dr. R. E. van der Hoeven Prof. dr. W. Hout Prof. dr. R. S. Gowricharn, Tilburg University Copromotor Dr S. A. Newman, Senior Lecturer, University of the West of England To my mother, Fatú, and her caring and selfless nature Contents List of Tables, Figures and Appendices ix Acronyms xii Preface and Acknowledgments xiv Abstract xviii Samenvatting xxi Introduction 1.1. -

Cape Verde: the Case for Euroization

CAPE VERDE: THE CASE FOR EUROIZATION João Loureiro Manuel M.F. Martins Ana Paula Ribeiro [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] CEMPRE*, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto Rua Dr. Roberto Frias s/n, 4200-464 Porto, Portugal February 2009 PRELIMINARY Abstract After 10 years of a fixed exchange rate against the Euro and a deepening integration with the European Union (EU), the authorities of Cape Verde maintain a strong commitment to nominal stability and are now considering the official euroization of the country. Compared to the current pegging, euroization could be costly if the structural and/or cyclical conditions of Cape Verde were to require control over the interest rates and the exchange rate. Given the strong economic and financial integration between Cape Verde and Europe, and the fact that Cape Verde records inflation rates at levels that are similar to those of the Euro Area (EA), the relevant issue is whether the ECB monetary policy fits the needs of Cape Verde. In order to answer this question, we empirically assess the synchronization between the business cycle of Cape Verde and the business cycle of the EA. For that purpose, we compute output gaps and then use conventional correlation measures as well as other techniques recently suggested in the literature. Replicating the methodology for each of the 27 EU member-states, our results show that Cape Verde ranks better than several EU countries and even some EA countries. We thus conclude that there is a strong case for the euroization of Cape Verde. -

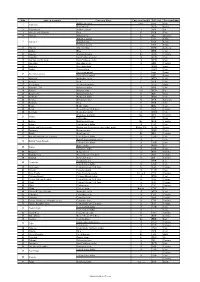

EQ Pay Currencies

EQ Pay Currencies Country Currency Code Currency Name Country Currency Code Currency Name Albania ALL Albanian Lek Kazakhstan KZT Kazakh Tenge Algeria DZD Algerian Dinar Kyrgyzstan KGS Kyrgyz Som Angola AOA Angolan Kwanza Laos LAK Laotian Kip Armenia AMD Armenian Dram Lebanon LBP Lebanese Pound Aruba AWG Aruban Florin Lesotho LSL Lesotho Loti Azerbaijan AZN Azerbaijani Manat Liberia LRD Liberian Dollar Bahamas BSD Bahamian Dollar Libya LYD Libyan Dinar Bangladesh BDT Bangladeshi Taka Macau MOP Macanese Patacca Belarus BYN Belarusian Ruble Madagascar MGA Malagasy Ariary Belize BZD Belizean Dollar Malawi MWK Malawian Kwacha Benin XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Malaysia MYR Malaysian Ringgit Bermuda BMD Bermudian Dollar Maldives MVR Maldives Rufiyaa Bolivia BOB Bolivian Boliviano Mali XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Bosnia BAM Bosnian Marka Mauritania MRU Mauritanian Ouguiya Botswana BWP Botswana pula Moldova MDL Moldovan Leu Brazil BRL Brazilian Real Mongolia MNT Mongolian Tugrik Brunei BND Bruneian Dollar Mozambique MZN Mozambique Metical Bulgaria BGN Bulgarian Lev Myanmar MMK Myanmar Kyat Burkina Faso XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Namibia NAD Namibian Dollar Netherlands Antillean Burundi BIF Burundi Franc Netherlands Antilles ANG Dollar Cambodia KHR Cambodian Riel New Caledonia XPF CFP Franc Nicaraguan Gold Cameroon XAF CFA Franc BEAC Nicaragua NIO Cordoba Cape Verde Island CVE Cape Verdean Escudo Niger XOF CFA Franc BCEAO Cayman Islands KYD Caymanian Dollar Nigeria NGN Nigerian Naira Central African XAF CFA Franc BEAC North Macedonia MKD Macedonian Denar Republic Chad -

A Curriculum on Cape Verde

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1994 A curriculum on Cape Verde. Amelia Ambrose Rebeiro University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Ambrose Rebeiro, Amelia, "A curriculum on Cape Verde." (1994). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 5109. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/5109 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CURRICULUM ON CAPE VERDE A Dissertation Presented by AMELIA AMBROSE REBEIRO Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillments of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION MAY 1994 SCHOOL OF EDUCATION ©Amelia Ambrose Rebeiro 1994 All Rights Reserved A CURRICULUM ON CAPE VERDE A Dissertation Presented by AMELIA AMBROSE-REBEIRO Bailey W. Jackson, Dean School of Education) DEDICATION I want to dedicate my dissertation to my mother, Amelia Pires Rebeiro, who shares my joy of accomplishment. My mother's constant prayers, encouragement, and love throughout my growing up and her attitude that one should not give up, helped me complete this dissertation; also my sons Jamie and Derrick, my eight brothers and three sisters. Finally to my grandchildren Brooke Nicole, Derrick Michael II, Diandra Rae, Taj Azel, and Denzel Keith who inspired me to develop a curriculum to enhance and strengthen their knowledge of the Cape Verdean culture. -

Feasibility of a Leasing Sector in Cape Verde Φ

V.1 Eng Codaven FEASIBILITY OF A LEASING SECTOR IN CAPE VERDE March-April 2007 Codaven March-April 2007 1 V.1 Eng Codaven TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 4 2. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1. Scope of the work (sow) and limitation. ................................................................. 7 2.2. Background ............................................................................................................... 7 3. CAPE VERDEAN ECONOMY ...................................................................................... 11 3.1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 3.2. Economic Indicators for Cape Verde ................................................................... 12 3.3. Conclusions of the chapter “Cape Verdean Economy”. ..................................... 14 4. FINANCIAL SECTOR. .................................................................................................. 15 4.1. Introduction. ........................................................................................................... 15 4.2 The legal framework. ............................................................................................. 15 4.3. The Central Bank. ................................................................................................. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Cape Verde – Employer of Record

Cape Verde – Employer of Record Globalization Partners provides employer of record services for customers that want to hire employees and run payroll without first establishing a branch office or subsidiary in Cape Verde. Your candidate is hired via Globalization Partners’ Cape Verde PEO in accordance with local labor laws and can be onboarded in days instead of the months it typically takes. The individual is assigned to work on your team, working on your company’s behalf exactly as if he or she were your employee to fulfill your in-country requirements. Table of Contents Overview of Cape Verde Employment Contracts in Cape Verde Cape Verde Holidays Why Globalization Partners Our solution enables customers to run payroll in Cape Verde while HR services, tax, and compliance management matters are lifted from their shoulders onto ours. As a Global PEO expert, we manage employment contract best practices, statutory and market norm benefits, and employee expenses, as well as severance and termination if required. We also keep you apprised of changes to local employment laws in Cape Verde. Your new employee is productive sooner, has a better hiring experience and is 100% dedicated to your team. You’ll have peace of mind knowing you have a team of dedicated employment experts assisting with every hire. Globalization Partners allows you to harness the talent of the brightest people in more than 187 countries around the world, quickly and painlessly. Overview of Cape Verde Cape Verde is archipelago off the coast of western Africa and has a population of about 55,000. The capital city of Cape Verde is Praia which has a population of 160,000. -

Currencies of the World

The World Trade Press Guide to Currencies of the World Currency, Sub-Currency & Symbol Tables by Country, Currency, ISO Alpha Code, and ISO Numeric Code € € € € ¥ ¥ ¥ ¥ $ $ $ $ £ £ £ £ Professional Industry Report 2 World Trade Press Currencies and Sub-Currencies Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies of the World of the World World Trade Press Ta b l e o f C o n t e n t s 800 Lindberg Lane, Suite 190 Petaluma, California 94952 USA Tel: +1 (707) 778-1124 x 3 Introduction . 3 Fax: +1 (707) 778-1329 Currencies of the World www.WorldTradePress.com BY COUNTRY . 4 [email protected] Currencies of the World Copyright Notice BY CURRENCY . 12 World Trade Press Guide to Currencies and Sub-Currencies Currencies of the World of the World © Copyright 2000-2008 by World Trade Press. BY ISO ALPHA CODE . 20 All Rights Reserved. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work without the express written permission of the Currencies of the World copyright holder is unlawful. Requests for permissions and/or BY ISO NUMERIC CODE . 28 translation or electronic rights should be addressed to “Pub- lisher” at the above address. Additional Copyright Notice(s) All illustrations in this guide were custom developed by, and are proprietary to, World Trade Press. World Trade Press Web URLs www.WorldTradePress.com (main Website: world-class books, maps, reports, and e-con- tent for international trade and logistics) www.BestCountryReports.com (world’s most comprehensive downloadable reports on cul- ture, communications, travel, business, trade, marketing, -

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

Monthly Economic Review- June 2015

MONTHLY ECONOMIC REVIEW MONTHLY ECONOMIC REVIEW CENTRAL BANK OF LIBERIA MONTHLY ECONOMIC REVIEW JUNE 2015 VOLUME 1 No. 6 MONTHLY ECONOMIC REVIEW MONTHLY ECONOMIC REVIEW Table 1: Performances of End-of-Period WAMZ Exchange Rates Against the US Dollar The Monthly Economic Review is produced by the Bank’s Research, Currency 15-May 15-Jun Policy & Planning Department. Inquiries concerning this Curr Unit./US$1 Curr Unit./US$1 M-on-M Rate of Appr (-)/Depr(+) publication should be addressed to: LRD 84.5 85.5 1.2 FCFA 602.0 589.2 -2.1 CVE 101.2 99.1 -2.1 GHC 4.0 4.3 8.3 The Director GMD 38.8 39.1 0.9 Research, Policy & Planning Department GNF 7,308.5 7,318.9 0.1 NGN 196.5 196.5 0.0 Central Bank of Liberia SLL 4,833.8 4,861.2 0.6 P. O. Box 2048 Sources: Central Banks of Liberia and WAMA:www.amao-wama.org/en/exchange.aspx and www.amao-wama.org/ LRD—Liberian Dollar Corner of Carey & Warren Streets, Monrovia, Liberia FCFA—Franc CFA CVE—Cape Verdean Escudo Contacts: +231-880-649103/886-246587/555-960556 GMD—Gambian Dalasi Fax: 00(231)77059642 GNF—Guinean Franc NGN—Nigerian Naira SLL—Sierra Leonean Leone USD—US Dollar GBP—British Pound 9 MONTHLY ECONOMIC REVIEW MONTHLY ECONOMIC REVIEW Jun-15 Monetary Policy Stance and Actions Mar-15 Apr-15 May-15 11 Inflation (In percent) Occasioned by depreciating pressure on the exchange rate, the CBL intervened in the Overall (Year-on-year) Rate of Inflation 7.3 6.8 7.9 7.7 foreign exchange market with US$ 3.0 million during June, up from US$2.0 million in a. -

All Countries and Their Currency Names List

List of all Countries and Currencies of the World in 2020 Country Currency Afghanistan Afghan afghani Albania Albanian lek Algeria Algerian dinar Andorra Euro Angola Kwanza Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar Argentina Argentine peso Armenia Armenian dram Australia Australian dollar Austria Euro Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat Bahamas Bahamian dollar Bahrain Bahraini dinar Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka Barbados Barbadian dollar Belarus Belarusian ruble Belgium Euro Belize Belize dollar Benin West African CFA franc Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Botswana Pula Brazil Brazilian real Brunei Brunei dollar Bulgaria Bulgarian lev Burkina Faso West African CFA franc Burundi Burundian franc Cambodia Cambodian riel Cameroon Central African CFA franc Canada Canadian dollar Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo Central African Republic Central African CFA franc Chad Central African CFA franc Chile Chilean peso China Chinese Yuan Renminbi Colombia Colombian peso Comoros Comorian franc Costa Rica Costa Rican colon Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) West African CFA franc Croatia Croatian kuna Cuba Cuban peso Cyprus Euro Czechia Czech koruna Democratic Republic of the Congo Congolese franc Denmark Danish krone Djibouti Djiboutian franc Dominica East Caribbean dollar Dominican Republic Dominican peso Ecuador United States dollar Egypt Egyptian pound El Salvador United States dollar Equatorial Guinea Central African CFA franc Eritrea Eritrean nakfa Estonia Euro Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Santiago Cape Verde Destination Guide

Santiago Cape Verde Destination Guide Overview of Santiago Cape Verde The largest island in the archipelago, and arguably boasting the best scenery, Santiago is also the most populated. Its residents are more traditionally African in culture than those on many of the other islands, which is reflected in their musical traditions, markets and the many festivals held during the year. Santiago is the site of Cape Verde's capital city, Praia, and the picturesque fishing town of Tarrafal. Praia has an interesting marine archaeology museum dedicated to documenting the various shipwrecks that have occurred around the islands. While not a popular tourist destination in its own right, Praia is the site of Cape Verde's busiest airport, and walking around the city is a pleasant way to spend an hour or two before venturing to another part of Santiago, or taking a ferry to one of the other islands. The interior of Santiago is characterised by two towering chains of mountains, while the coastline sports small, sandy, palm-fringed coves. Other sites of interest on the islands include the historic old port city, Cidade Velha, which was a major slave-trading post and retains cobbled lanes and stone buildings in the shadow of its old 15th-century fortress and cathedral. Cidade Velha was once the second richest city in the Portuguese empire but it was raided frequently by pirates and declined as the slave trade did. Key Facts Language: The official language is Portuguese and a patois known as Crioulo. Passport/Visa: Visitors of any nationality require a passport, valid for the period of six months after intended stay, to enter the Cape Verde Islands.