Morphology, Ontogeny, Reproduction, and Feeding of True Bugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tri-Ology Vol 58, No. 1

FDACS-P-00124 April - June 2020 Volume 59, Number 2 TRI- OLOGY A PUBLICATION FROM THE DIVISION OF PLANT INDUSTRY, BUREAU OF ENTOMOLOGY, NEMATOLOGY, AND PLANT PATHOLOGY Division Director, Trevor R. Smith, Ph.D. BOTANY ENTOMOLOGY NEMATOLOGY PLANT PATHOLOGY Providing information about plants: Identifying arthropods, taxonomic Providing certification programs and Offering plant disease diagnoses native, exotic, protected and weedy research and curating collections diagnoses of plant problems and information Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services • Division of Plant Industry 1 Phaenomerus foveipennis (Morimoto), a conoderine weevil. Photo by Kyle E. Schnepp, DPI ABOUT TRI-OLOGY TABLE OF CONTENTS The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services- Division of Plant Industry’s (FDACS-DPI) Bureau of Entomology, HIGHLIGHTS 03 Nematology, and Plant Pathology (ENPP), including the Botany Noteworthy examples from the diagnostic groups Section, produces TRI-OLOGY four times a year, covering three throughout the ENPP Bureau. months of activity in each issue. The report includes detection activities from nursery plant inspections, routine and emergency program surveys, and BOTANY 04 requests for identification of plants and pests from the public. Samples are also occasionally sent from other states or countries Quarterly activity reports from Botany and selected plant identification samples. for identification or diagnosis. HOW TO CITE TRI-OLOGY Section Editor. Year. Section Name. P.J. Anderson and G.S. Hodges ENTOMOLOGY 07 (Editors). TRI-OLOGY Volume (number): page. [Date you accessed site.] Quarterly activity reports from Entomology and samples reported as new introductions or interceptions. For example: S.E. Halbert. 2015. Entomology Section. P.J. Anderson and G.S. -

Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 5 Issue 1 Article 1 Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan Muhammad Shahbaz Chattha Women University Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Bagh (AJK), [email protected] Abu Ul Hassan Faiz Women University of Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Bagh (AJK), [email protected] Arshad Javid University of Veterinary & Animal Sciences, Lahore, [email protected] Irfan Baboo Cholistan University of Veterinary & Animal Sciences, Bahawalpur, [email protected] Inayat Ullah Malik The University of Lakki Marwat, Lakki Marwat, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Entomology Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Chattha, M. S., Faiz, A. H., Javid, A., Baboo, I., & Malik, I. U. (2018). Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan, Journal of Bioresource Management, 5 (1). DOI: https://doi.org/10.35691/JBM.8102.0081 ISSN: 2309-3854 online (Received: May 16, 2019; Accepted: Sep 19, 2019; Published: Jan 1, 2018) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diversity of Water Bugs in Gujranwala District, Punjab, Pakistan © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. -

UFRJ a Paleoentomofauna Brasileira

Anuário do Instituto de Geociências - UFRJ www.anuario.igeo.ufrj.br A Paleoentomofauna Brasileira: Cenário Atual The Brazilian Fossil Insects: Current Scenario Dionizio Angelo de Moura-Júnior; Sandro Marcelo Scheler & Antonio Carlos Sequeira Fernandes Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências: Patrimônio Geopaleontológico, Museu Nacional, Quinta da Boa Vista s/nº, São Cristóvão, 20940-040. Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil. E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Recebido em: 24/01/2018 Aprovado em: 08/03/2018 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.11137/2018_1_142_166 Resumo O presente trabalho fornece um panorama geral sobre o conhecimento da paleoentomologia brasileira até o presente, abordando insetos do Paleozoico, Mesozoico e Cenozoico, incluindo a atualização das espécies publicadas até o momento após a última grande revisão bibliográica, mencionando ainda as unidades geológicas em que ocorrem e os trabalhos relacionados. Palavras-chave: Paleoentomologia; insetos fósseis; Brasil Abstract This paper provides an overview of the Brazilian palaeoentomology, about insects Paleozoic, Mesozoic and Cenozoic, including the review of the published species at the present. It was analiyzed the geological units of occurrence and the related literature. Keywords: Palaeoentomology; fossil insects; Brazil Anuário do Instituto de Geociências - UFRJ 142 ISSN 0101-9759 e-ISSN 1982-3908 - Vol. 41 - 1 / 2018 p. 142-166 A Paleoentomofauna Brasileira: Cenário Atual Dionizio Angelo de Moura-Júnior; Sandro Marcelo Schefler & Antonio Carlos Sequeira Fernandes 1 Introdução Devoniano Superior (Engel & Grimaldi, 2004). Os insetos são um dos primeiros organismos Algumas ordens como Blattodea, Hemiptera, Odonata, Ephemeroptera e Psocopera surgiram a colonizar os ambientes terrestres e aquáticos no Carbonífero com ocorrências até o recente, continentais (Engel & Grimaldi, 2004). -

Incidence of Rice Bug,Leptocorisaoratorius (F.) (Hemiptera: Alydidae) Using White Muscardinefungus Beauveriabassiana (Bals.) Vuill.In Upland Rice

IJISET - International Journal of Innovative Science, Engineering & Technology, Vol. 1 Issue 10, December 2014. www.ijiset.com ISSN 2348 – 7968 Incidence of Rice Bug,Leptocorisaoratorius (F.) (Hemiptera: Alydidae) Using White MuscardineFungus Beauveriabassiana (Bals.) Vuill.In Upland Rice Pio P. Tuan, PhD* Department of Agricultural Sciences, College of Agriculture, Fisheries, and Natural Resources University of Eastern Philippines, University Town, Catarman, Northern Samar, Philippines Abstract A field experiment was conducted to evaluate the incidence of Rice bug, Leptocorisaoratorius(F.) using B. bassiana as mycoinsectice under upland conditions. Field population of L. oratorius was not significantly affected by B. bassiana7 DAS, but significant at 15 DAS. The application of B. bassiana did not significantly affect the damage caused by L. oratoriuson rice grains.The results suggest that B. bassiana cannot be used as a sole mortality factor in the management of rice bug under upland conditions. More field experimentations are necessary taking into consideration the influence of environmental factors and how these can be manipulated in favor of the fungal insecticide. Key Words: Conidia, substrate, microbial insecticide, upand rice, abiotic environmental factors INTRODUCTION Rice bug, Leptrocorisaoratorius (F.) is one of the major insect pests infesting rice in upland areas. Several species of rice bugs occur in the Philippines, but L. oratorius is the most prevalent (Reissig et al., 1986; Litsinger et al., 1987). Upland rice is usually cultivated for organic rice or with less application of fertilizer and pesticides. The increasing demand for organically produced foods including rice, has contributed to the adoption of ecologically oriented pest control methods. Consequently, reduced pesticide use has become a strong option to protect the environment and human health. -

Influence of Plant Parameters on Occurrence and Abundance Of

HORTICULTURAL ENTOMOLOGY Influence of Plant Parameters on Occurrence and Abundance of Arthropods in Residential Turfgrass 1 S. V. JOSEPH AND S. K. BRAMAN Department of Entomology, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of Georgia, 1109 Experiment Street, GrifÞn, GA 30223-1797 J. Econ. Entomol. 102(3): 1116Ð1122 (2009) ABSTRACT The effect of taxa [common Bermuda grass, Cynodon dactylon (L.); centipedegrass, Eremochloa ophiuroides Munro Hack; St. Augustinegrass, Stenotaphrum secundatum [Walt.] Kuntze; and zoysiagrass, Zoysia spp.], density, height, and weed density on abundance of natural enemies, and their potential prey were evaluated in residential turf. Total predatory Heteroptera were most abundant in St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass and included Anthocoridae, Lasiochilidae, Geocoridae, and Miridae. Anthocoridae and Lasiochilidae were most common in St. Augustinegrass, and their abundance correlated positively with species of Blissidae and Delphacidae. Chinch bugs were present in all turf taxa, but were 23Ð47 times more abundant in St. Augustinegrass. Anthocorids/lasiochilids were more numerous on taller grasses, as were Blissidae, Delphacidae, Cicadellidae, and Cercopidae. Geocoridae and Miridae were most common in zoysiagrass and were collected in higher numbers with increasing weed density. However, no predatory Heteroptera were affected by grass density. Other beneÞcial insects such as staphylinids and parasitic Hymenoptera were captured most often in St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass. These differences in abundance could be in response to primary or alternate prey, or reßect the inßuence of turf microenvironmental characteristics. In this study, SimpsonÕs diversity index for predatory Heteroptera showed the greatest diversity and evenness in centipedegrass, whereas the herbivores and detritivores were most diverse in St. Augustinegrass lawns. These results demonstrate the complex role of plant taxa in structuring arthropod communities in turf. -

(Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cydnidae) from Caribbean

Advances in Entomology, 2014, 2, 87-91 Published Online April 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ae http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ae.2014.22015 A New Species of Dallasiellus Berg (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cydnidae) from Caribbean Leonel Marrero Artabe1*, María C. Mayorga Martínez2 1University of Matanzas, Matanzas, Cuba 2Institute of Biology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), México City, México Email: *[email protected] Received 7 February 2014; revised 21 March 2014; accepted 1 April 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract The genus Dallasiellus Berg (Hemiptera: Cydnidae) is revised with the description of a new species from Caribbean, Dallasiellus varaderensis nov. sp. A diagnosis of species is based on external morphology of males and genitalia examination. Dorsal view of adults and parameres are illu- strated. Notes about their biology and host plants are briefly discussed. Keywords Burrower Bugs, Dallasiellus, New Species, Diagnoses, Turfgrass, Caribbean 1. Introduction Members of the Cydnidae family are called burrowing bugs; more than 88 genera and about 680 species are recorded [1]. They have generally been considered of little economic importance, but up to date almost 30 spe- cies have been reported as pests [2]-[4]. Some species causing damages on turfgrass in a Golf Club from Carib- bean have been detected recently [5]. However, the biological information about these insects is not very well-known yet. One of the most important studies of this group was the Revision of the Western Hemisphere fauna of Cydni- dae carried out by Froeschner [6]. -

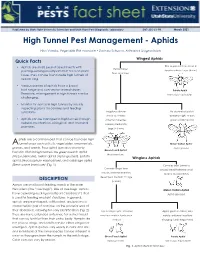

High Tunnel Pest Management - Aphids

Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory ENT-225-21-PR March 2021 High Tunnel Pest Management - Aphids Nick Volesky, Vegetable IPM Associate • Zachary Schumm, Arthropod Diagnostician Winged Aphids Quick Facts • Aphids are small, pear-shaped insects with Thorax green; no abdominal Thorax darker piercing-sucking mouthparts that feed on plant dorsal markings; large (4 mm) than abdomen tissue. They can be found inside high tunnels all season long. • Various species of aphids have a broad host range and can vector several viruses. Potato Aphid Therefore, management in high tunnels can be Macrosipu euphorbiae challenging. • Monitor for aphids in high tunnels by visually inspecting plants for colonies and feeding symptoms. Irregular patch on No abdominal patch; dorsal abdomen; abdomen light to dark • Aphids can be managed in high tunnels through antennal tubercles green; small (<2 mm) cultural, mechanical, biological, and chemical swollen; medium to practices. large (> 3 mm) phids are a common pest that can be found on high Atunnel crops such as fruits, vegetables, ornamentals, Melon Cotton Aphid grasses, and weeds. Four aphid species commonly Aphis gossypii Green Peach Aphid found in Utah in high tunnels are green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Myzus persicae), melon aphid (Aphis gossypii), potato Wingless Aphids aphid (Macrosiphum euphorbiae), and cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae) (Fig. 1). Cornicles short (same as Cornicles longer than cauda); head flattened; small cauda; antennal insertions (2 mm), rounded body DESCRIPTION developed; medium to large (> 3mm) Aphids are small plant feeding insects in the order Hemiptera (the “true bugs”). Like all true bugs, aphids Melon Cotton Aphid have a piercing-sucking mouthpart (“proboscis”) that Aphis gossypii is used for feeding on plant structures. -

An Overview of Flat Bug Genera (Hemiptera, Aradidae)

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Denisia Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 0019 Autor(en)/Author(s): Lariviere Marie C., Larochelle Andre Artikel/Article: An overview of flat bug genera (Hemiptera, Aradidae) from New Zealand, with considerations on faunal diversification and affinities 181-214 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at An overview of flat bug genera (Hemiptera, Aradidae) from New Zealand, with considerations on faunal diversification and affinities1 M .-C . L ARIVIÈRE & A. L AROCHELLE Abstract: Nineteen genera and thirty-nine species of Aradidae have been described from New Zealand, most of which are endemic (12 genera, 38 species). An overview of all genera and an identification key to subfamilies, tribes, and genera are presented for the first time. Species included in each genus are list- ed for New Zealand. Concise generic descriptions, illustrations emphasizing key diagnostic features, colour photographs representing each genus, an overview of the most relevant literature, and notes on distribution are also given. The biology and diversification of New Zealand aradids, and their affinities with neighbouring faunas are briefly discussed. Key words: Aradidae, biogeography, Hemiptera, New Zealand, taxonomy. Introduction forests, and using their stylets to extract liq- uids from fungal hyphae associated with de- The Aradidae, also commonly referred caying wood. Many ground-dwelling species to as flat bugs or bark bugs, form a large fam- of rainforest environments are wingless – a ily of Heteroptera containing over 1,800 condition thought to have evolved several species and 210 genera worldwide (SCHUH times in the phylogeographic history of the & SLATER 1995). -

Vectors of Chagas Disease, and Implications for Human Health1

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Denisia Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 0019 Autor(en)/Author(s): Jurberg Jose, Galvao Cleber Artikel/Article: Biology, ecology, and systematics of Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae), vectors of Chagas disease, and implications for human health 1095-1116 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Biology, ecology, and systematics of Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae), vectors of Chagas disease, and implications for human health1 J. JURBERG & C. GALVÃO Abstract: The members of the subfamily Triatominae (Heteroptera, Reduviidae) are vectors of Try- panosoma cruzi (CHAGAS 1909), the causative agent of Chagas disease or American trypanosomiasis. As important vectors, triatomine bugs have attracted ongoing attention, and, thus, various aspects of their systematics, biology, ecology, biogeography, and evolution have been studied for decades. In the present paper the authors summarize the current knowledge on the biology, ecology, and systematics of these vectors and discuss the implications for human health. Key words: Chagas disease, Hemiptera, Triatominae, Trypanosoma cruzi, vectors. Historical background (DARWIN 1871; LENT & WYGODZINSKY 1979). The first triatomine bug species was de- scribed scientifically by Carl DE GEER American trypanosomiasis or Chagas (1773), (Fig. 1), but according to LENT & disease was discovered in 1909 under curi- WYGODZINSKY (1979), the first report on as- ous circumstances. In 1907, the Brazilian pects and habits dated back to 1590, by physician Carlos Ribeiro Justiniano das Reginaldo de Lizárraga. While travelling to Chagas (1879-1934) was sent by Oswaldo inspect convents in Peru and Chile, this Cruz to Lassance, a small village in the state priest noticed the presence of large of Minas Gerais, Brazil, to conduct an anti- hematophagous insects that attacked at malaria campaign in the region where a rail- night. -

Giant Water Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Belostomatidae) of Israel

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGY, Vol. 48 (1), pp. 119–141 (30 December 2018) A review of the giant water bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Nepomorpha: Belostomatidae) of Israel TANYA NOVOSELSKY 1, PING -P ING CHEN 2 & NI C O NIESER 2 1The Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Israel National Center for Biodiversity Studies, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel. E-mail: [email protected] 2Naturalis Biodiversity Centre, P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT An updated and annotated check-list of Israeli giant water bugs (Belostomatidae) is provided. The recorded species belong in the subfamilies Belostomatinae and Lethocerinae. The following six species occur in the country: Appasus urinator urinator, Limnogeton fieberi, Lethocerus patruelis, Lethocerus cordofanus (new record), Hydrocyrius colombiae colombiae (new record) and Belostoma bifo ve olatum (new record). Belostoma bifoveolatum was previously known only from South America, so it is recorded in the Old World for the first time. An illustrated identification key is compiled for the Israeli Belostomatidae species. A list of exotic Belostomatidae material accumulated in the collection of the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History is provided. KEYWORDS: Hemiptera, Heteroptera, Nepomorpha, Belostomatidae, aquatic in sects, giant water bugs, identification key, male genitalia, Middle East, ta xonomy. INTRODUCTION The Belostomatidae is a family of aquatic heteropterans of almost world-wide distribution, although its greatest diversity is observed in the tropics (Merritt & Cummins 1996; Schuh & Slater 1995). The family includes the largest—up to 120 mm long—representatives of Heteroptera, which are known as the giant water bugs or electric-light bugs, because they are attracted to light sources at night (Ri- beiro et al. -

Insects of Larose Forest (Excluding Lepidoptera and Odonates)

Insects of Larose Forest (Excluding Lepidoptera and Odonates) • Non-native species indicated by an asterisk* • Species in red are new for the region EPHEMEROPTERA Mayflies Baetidae Small Minnow Mayflies Baetidae sp. Small minnow mayfly Caenidae Small Squaregills Caenidae sp. Small squaregill Ephemerellidae Spiny Crawlers Ephemerellidae sp. Spiny crawler Heptageniiidae Flatheaded Mayflies Heptageniidae sp. Flatheaded mayfly Leptophlebiidae Pronggills Leptophlebiidae sp. Pronggill PLECOPTERA Stoneflies Perlodidae Perlodid Stoneflies Perlodid sp. Perlodid stonefly ORTHOPTERA Grasshoppers, Crickets and Katydids Gryllidae Crickets Gryllus pennsylvanicus Field cricket Oecanthus sp. Tree cricket Tettigoniidae Katydids Amblycorypha oblongifolia Angular-winged katydid Conocephalus nigropleurum Black-sided meadow katydid Microcentrum sp. Leaf katydid Scudderia sp. Bush katydid HEMIPTERA True Bugs Acanthosomatidae Parent Bugs Elasmostethus cruciatus Red-crossed stink bug Elasmucha lateralis Parent bug Alydidae Broad-headed Bugs Alydus sp. Broad-headed bug Protenor sp. Broad-headed bug Aphididae Aphids Aphis nerii Oleander aphid* Paraprociphilus tesselatus Woolly alder aphid Cicadidae Cicadas Tibicen sp. Cicada Cicadellidae Leafhoppers Cicadellidae sp. Leafhopper Coelidia olitoria Leafhopper Cuernia striata Leahopper Draeculacephala zeae Leafhopper Graphocephala coccinea Leafhopper Idiodonus kelmcottii Leafhopper Neokolla hieroglyphica Leafhopper 1 Penthimia americana Leafhopper Tylozygus bifidus Leafhopper Cercopidae Spittlebugs Aphrophora cribrata -

Identification, Biology, Impacts, and Management of Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Soybean and Corn in the Midwestern United States

Journal of Integrated Pest Management (2017) 8(1):11; 1–14 doi: 10.1093/jipm/pmx004 Profile Identification, Biology, Impacts, and Management of Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Soybean and Corn in the Midwestern United States Robert L. Koch,1,2 Daniela T. Pezzini,1 Andrew P. Michel,3 and Thomas E. Hunt4 1 Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, 1980 Folwell Ave., Saint Paul, MN 55108 ([email protected]; Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article-abstract/8/1/11/3745633 by guest on 08 January 2019 [email protected]), 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected], 3Department of Entomology, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University, 210 Thorne, 1680 Madison Ave. Wooster, OH 44691 ([email protected]), and 4Department of Entomology, University of Nebraska, Haskell Agricultural Laboratory, 57905 866 Rd., Concord, NE 68728 ([email protected]) Subject Editor: Jeffrey Davis Received 12 December 2016; Editorial decision 22 March 2017 Abstract Stink bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) are an emerging threat to soybean and corn production in the midwestern United States. An invasive species, the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Sta˚ l), is spreading through the region. However, little is known about the complex of stink bug species associ- ated with corn and soybean in the midwestern United States. In this region, particularly in the more northern states, stink bugs have historically caused only infrequent impacts to these crops. To prepare growers and agri- cultural professionals to contend with this new threat, we provide a review of stink bugs associated with soybean and corn in the midwestern United States.