The Philippine Security Situation in 2011: Plugging the (Very Big) Holes in External Defense While Continuing to Face Internal Vulnerabilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Workplaces with the Rockwell Mother's May

MAY 2016 www.lopezlink.ph http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Registration is ongoing! See details on page 10. #Halalan2016: All for the Filipino familyBy Carla Paras-Sison ABS-CBN Corporation launches its election coverage campaign about a year before election day. But it’s not protocol. Ging Reyes, head of ABS-CBN Integrated News and Current Affairs (INCA), says it actually takes the team a year to prepare for the elections. Turn to page 6 Workplaces with Mornings Mother’s the Rockwell with the May touch…page 2 ‘momshies’…page 4 …page 12 Lopezlink May 2016 Lopezlink May 2016 Biz News Biz News 2015 AUDITED FINANCIAL RESULTS Period Dispatch from Japan Total revenues Net income attributable to equity January- holders of the parent Building Mindanao’s September Workplaces with Design-driven PH products showcased in 2014 2015 % change 2014 2015 % change By John ALFS fest Porter ABS-CBN P33.544B P38.278B +14 P2.387B P2.932B +23 largest solar farm Lopez Holdings P99.191B P96.510B -3 P3.760B P6.191B +65 theBy Rachel Varilla Rockwell touch KIRAHON Solar Energy cure ERC [Energy Regulatory ing to the project’s success,” said EDC P30.867B P34.360B +11 P11.681B P7.642B -34 Corporation (KSEC) has for- Commission] approval and the KSEC CEO Mike Lichtenfeld. First Gen $1.903B $1,836B -4 $193.2M $167.3M -13 DELIVERING the same me- As the first mally inaugurated its 12.5- first to secure local nonrecourse Kirahon Solar Farm is First FPH P99.307B P96.643 -3 P5.632B P5.406B -4 ticulous standards it dedicated prime of- megawatt Kirahon Solar Farm debt financing, it was important Balfour’s second solar power ROCK P8.853B P8.922B +1 P1.563B P1.644B +5 to its residential developments, fice project of in Misamis Oriental. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

20 Century Ends

New Year‟s Celebration 2013 20th CENTURY ENDS ANKIND yesterday stood on the threshold of a new millennium, linked by satellite technology for the most closely watched midnight in history. M The millennium watch was kept all over the world, from a sprinkle of South Pacific islands to the skyscrapers of the Americas, across the pyramids, the Parthenon and the temples of Angkor Wat. Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle said Filipinos should greet 2013 with ''great joy'' and ''anticipation.'' ''The year 2013 is not about Y2K, the end of the world or the biggest party of a lifetime,'' he said. ''It is about J2K13, Jesus 2013, the Jubilee 2013 and Joy to the World 2013. It is about 2013 years of Christ's loving presence in the world.'' The world celebration was tempered, however, by unease over Earth's vulnerability to terrorism and its dependence on computer technology. The excitement was typified by the Pacific archipelago nation of Kiribati, so eager to be first to see the millennium that it actually shifted its portion of the international dateline two hours east. The caution was exemplified by Seattle, which canceled its New Year's party for fear of terrorism. In the Philippines, President Benigno Aquino III is bracing for a “tough” new year. At the same time, he called on Filipinos to pray for global peace and brotherhood and to work as one in facing the challenges of the 21st century. Mr. Estrada and at least one Cabinet official said the impending oil price increase, an expected P60- billion budget deficit, and the public opposition to amending the Constitution to allow unbridled foreign investments would make it a difficult time for the Estrada presidency. -

FOURTH ANNIVERSARY FORUM of ARANGKADA PHILIPPINES March 3, 2015 | Rizal Ballroom, Makati Shangri-La Hotel

! FOURTH ANNIVERSARY FORUM OF ARANGKADA PHILIPPINES March 3, 2015 | Rizal Ballroom, Makati Shangri-La Hotel Welcoming Remarks and Introduction of Guest Speaker By Mr. Rhicke Jennings President, American Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines, Inc. Managing Director of Indonesia and Philippines, Fedex Express as delivered by Mr. Ebb Hinchliffe Executive Director, American Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines, Inc. (Good morning everyone it’s my pleasure to say) Ladies and gentlemen, (from the) our private and public sector and, (our) media partners, (of course) our partners in the business associations, (our) corporate sponsors (that we couldn’t do without), (our) diplomats, (our) friends around the world watching our (on the) webcast, I have the distinct pleasure on behalf of the Joint Foreign Chambers to welcome all of you to the fourth annual Arangkada Philippines Forum. My name is Rhicke Jennings. I am president of the American Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines, the first American chamber outside the United States. (My name is Ebb Hinchliffe I am the Executive Director for the American Chamber of Commerce Philippines it’s the first American Chamber outside the United States. Some of you may be reading the program saying, “what’s Ebb doing up there” about 7:45 this morning I got a call from our President Mr. Rhicke Jennings who said that he was sick and would not be able to attend today. I know Rhicke very well, if Rhicke could be here, he would be here. And the way he sounded on the phone he was definitely quite sick. He said he got up and tried to put his clothes on and just couldn’t make it so therefore it’s my honor to able to read Rhicke’s speech for him. -

The Commission on Elections from Aquino to Arroyo

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with deep gratitude to IDE that I had a chance to visit and experience Japan. I enjoyed the many conversations with researchers in IDE, Japanese academics and scholars of Philippines studies from various universities. The timing of my visit, the year 2009, could not have been more perfect for someone interested in election studies. This paper presents some ideas, arguments, proposed framework, and historical tracing articulated in my Ph.D. dissertation submitted to the Department of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I would like to thank my generous and inspiring professors: Paul Hutchcroft, Alfred McCoy, Edward Friedman, Michael Schatzberg, Dennis Dresang and Michael Cullinane. This research continues to be a work in progress. And while it has benefited from comments and suggestions from various individuals, all errors are mine alone. I would like to thank the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE) for the interest and support in this research project. I am especially grateful to Dr. Takeshi Kawanaka who graciously acted as my counterpart. Dr. Kawanaka kindly introduced me to many Japanese scholars, academics, and researchers engaged in Philippine studies. He likewise generously shared his time to talk politics and raise interesting questions and suggestions for my research. My special thanks to Yurika Suzuki. Able to anticipate what one needs in order to adjust, she kindly extended help and shared many useful information, insights and tips to help me navigate daily life in Japan (including earthquake survival tips). Many thanks to the International Exchange and Training Department of IDE especially to Masak Osuna, Yasuyo Sakaguchi and Miyuki Ishikawa. -

Knowledge Channel Powers Through Challenging Times Story on Page 4

NOVEMBER 2020 A monthly publication of the Lopez group of companies www.lopezlink.ph http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Knowledge Channel powers through challenging times Story on page 4 Economic impact assessment Rockwell Kapamilya ‘TVP’ partners with Christmas streams on TGN Realty presents YouTube …page 2 …page 7 …page 8 2 Lopezlink November 2020 BIZ NEWS BIZ NEWS Lopezlink November 2020 3 Virtual corporate governance training First Gen gets DOE award to Rockwell enters partnership By Carla Paras-Sison FGEN LNG preferred tenderers THE annual corporate gover- develop pump storage project with TGN Realty to develop nance training of directors and By Joel Gaborni for binding invitation to officers of publicly listed com- panies (PLCs) associated with FIRST Gen Corporation has always available when it’s security and stability. the Lopez Group went virtual been awarded a hydro service needed,” said Ricky Carandang, The hydro service contract mixed-use community on Oct. 23 as conducted by the contract by the Department of First Gen vice president. “But gives First Gen, through First tender for charter of FSRU Institute of Corporate Direc- Energy to develop a 120-mega- with a pump storage facility Gen Hydro, five years to con- venture with the family be- one bedroom to three bedrooms tors (ICD). watt (MW) pumped-storage like the one we want to build in duct predevelopment stage FGEN LNG Corporation has Ltd. and Höegh LNG Asia construction, ownership and hind the successful Nepo Cen- sized 44 sq. m. to 142 sq. m. The The continuing education hydroelectric facility in Aya, Pantabangan, we will be able to activities—from a preliminary expanded the list of preferred Pte. -

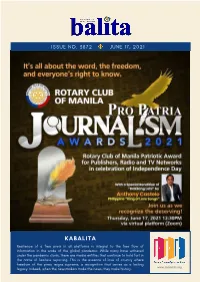

KABALITA Resilience of a Free Press in All Platforms Is Integral to the Free Flow of Information in the Wake of the Global Pandemic

ISSUE NO. 3872 JUNE 17, 2021 KABALITA Resilience of a free press in all platforms is integral to the free flow of information in the wake of the global pandemic. While many have withered under the pandemic storm, there are media entities that continue to hold fort in the name of fearless reporting. This is the essence of love of country where freedom of the press reigns supreme, a recognition that serves as a lasting legacy. Indeed, when the newsmakers make the news, they make history. www.rcmanila.org TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM TIMETABLE 03 MANILA ROTARIAN IN FOCUS 48 STAR Rtn. Teddy Kalaw, IV THE HISTORY OF THE ROTARY 06 CLUB OF MANILA BASIC EDUCATION AND JOURNALISM AWARDS 55 LITERACY 27 PRESIDENT'S CORNER COMMUNITY ECONOMIC Robert “Bobby” Lim Joseph, Jr. 57 DEVELOPMENT 28 THE WEEK THAT WAS 58 INTERNATIONAL SERVICE CLUB ADMINISTRATION 32 From the Programs Committee 60 INTERCLUB RELATIONS Programs Committee Holds Meeting Attendance THE ROTARY FOUNDATION List of Those Who Have Paid Their 62 Annual Dues Know your Rotary Club of Manila ROTARY INFORMATION Constitution, By-Laws and Policies 63 Rotary Youth Leadership Awards Board of Directors of the Rotary Club of Manila for RY 2020-2021 Holds 25th Special Meeting 65 OTHER MATTERS Board of Directors of the Rotary Club Quotes on Life by PP Frank Evaristo of Manila for RY 2021-2022 Holds Second Planning Meeting 66 ROTARY CLUB OF MANILA BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND RCMANILA FOUNDATION, INC. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS, 39 RY 2020-2021 40 VOCATIONAL SERVICE RCM BALITA EDITORIAL TEAM, RY 2020-2021 46 COGS IN THE WHEEL Rotary Club of Manila Newsletter balita June 17, 2021 02 Zoom Weekly Membership Luncheon Meeting Pro Patria Journalism Awards 2021 Rotary Year 2020-2021 Thursday, June 17, 2021, 12:30 PM PROGRAM TIMETABLE 11:30 AM Registration and Zoom In Program Moderator/Facilitator/ChikaTalk Rtn. -

State of the Nation Address of His Excellency Benigno S. Aquino III President of the Philippines to the Congress of the Philippines

State of the Nation Address of His Excellency Benigno S. Aquino III President of the Philippines To the Congress of the Philippines [This is an English translation of the speech delivered at the Session Hall of the House of Representatives, Batasang Pambansa Complex, Quezon City, on July 27, 2015] Thank you, everyone. Please sit down. Before I begin, I would first like to apologize. I wasn’t able to do the traditional processional walk, or shake the hands of those who were going to receive me, as I am not feeling too well right now. Vice President Jejomar Binay; Former Presidents Fidel Valdez Ramos and Joseph Ejercito Estrada; Senate President Franklin Drilon and members of the Senate; Speaker Feliciano Belmonte, Jr. and members of the House of Representatives; Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno and our Justices of the Supreme Court; distinguished members of the diplomatic corps; members of the Cabinet; local government officials; members of the military, police, and other uniformed services; my fellow public servants; and, to my Bosses, my beloved countrymen: Good afternoon to you all. [Applause] This is my sixth SONA. Once again, I face Congress and our countrymen to report on the state of our nation. More than five years have passed since we put a stop to the culture of “wang-wang,” not only in our streets, but in society at large; since we formally took an oath to fight corruption to eradicate poverty; and since the Filipino people, our bosses, learned how to hope once more. My bosses, this is the story of our journey along the Straight Path. -

LOPEZLINK April 07.Indd

April 2007 Star maker WONDERING how to strike a happy balance between Hinintay, Basta’t Kasama Kita, Hiram, Gulong ng Palad, harried mothers on one hand and hyperactive kids on the Sa Piling Mo, Panday and Pedro Penduko, variety shows other this summer? Why not give Mom a break and entrust ASAP Mania, MTB, comedy for Yes Yes Show Clown in A the little darlings for a few weeks to the ABS-CBN Center A Million, Yachang, reality shows Star in Million, Star Cir- for Communications Arts Inc. (CCAI), or more popularly cle Quest, Pinoy Big Brother and Pinoy Dream Academy, May bago sa amin...p.3 known as WORKSHOPS@ABS-CBN. among others. They have conducted training for Studio 23 The Company VJ’s, hosts and sportscasters, pageant contestants, and RNG WORKSHOPS@ABS-CBN is the fi rst network-based production staff. Big multi-national companies J&J, P&G, training arm that offers year-round, courses in Performing, Nestle and Unilever and big schools and NGOs have also Broadcast and Media Arts and Self-Development fi elds. tapped them for training. Led by Star Mentor Beverly Vergel and her team, the group Controlling its Destiny provides training to ABS-CBN’s stable of artists, celebri- In the 1970s, ABS-CBN was home to the country’s top ties, TV shows, movie projects, the public, career profes- artists, this distinction the network sought to reclaim in the sionals, business executives, corporate or elite confi dential 1990s after completing much of its post-martial law house- clients, and politicians. cleaning. -

Utang Na Loob (Deeply Indebted): the “MCC Effect” and Culture of Power in the Philippines

2009 Utang na Loob (Deeply Indebted): The “MCC Effect” and Culture of Power in the Philippines Brigitte Brown (Fletcher 2010), Madeline Gardner (LA 2010), Kelsi Stine (LA 2010, Fletcher 2011), Cody Valdes (LA 2012) Institute for Global Leadership, Tufts University 12/1/2009 Utang na Loob (Deeply Indebted): The “MCC Effect” and Culture of Power in the Philippines I. E X E C U T I V E SU M M A R Y In March 2009, four undergraduate and graduate students from the Poverty and Power Research Initiative (PPRI) at Tufts University’s Institute for Global Leadership travelled to the Philippines to study the causes of poverty in relation to the work of the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), a United States international aid program. This research trip was intended to produce the second in a series of case studies about poverty, inequality, and the MCC that began with research in Guatemala between September 2007 and August 2008, in conjunction with the Institute for Central American Strategic Studies. Both the MCC’s use of aid conditionality to encourage governance reform and its annual publication of independently measured governance scorecard ideally accommodated the students’ interest in understanding the connections between political economy, poverty, and the formal and informal institutions of national governance. The twelve-day trip to the Philippines was preceded by interview-based research in Washington, DC. There, PPRI students met with representatives of the MCC, World Bank, Philippine Embassy, Center for Global Development, and Global Integrity. In Manila, the students met with members of the Philippine private sector, government, NGO community, academia, journalism, and civil society as well as the US Embassy, USAID, and the greater international aid community. -

A Golden Celebration

March 2010 In honor of Oscar M. Lopez’s 80th birthday, catch the exclusive musicale Undaunted on April 23, 3 p.m. and 7 p.m. Available online at www.Lopezlink.ph @ the Meralco Theater A golden KCh leads the change celebration ...page 3 The rising stars of ‘PBB Double Up’…page 5 AT 50, the Lopez Memorial Museum and Library has become As the museum looks forward to the next 50 years, OML an institution in the truest and best sense of the word—dignified stressed, its “relevance will continue unabated, and it will continue and authoritative. Yet, like a cool aunt or uncle, it is also unself- to serve” the Filipino. conscious enough to throw off the trappings and take on a newer, MML, who also serves as president of Eugenio Lopez Foun- hipper era, as was evident in the exhibit cum book launch that dation Inc., introduced the commemorative volume “Unfolding: formally kicked off its golden year at the Rockwell Tent on Feb. Half a Century of the Lopez Memorial Museum and Library.” Au- 18. thored by former consultants Joselina Cruz and Serafin Quiason, Lopez Group chairman and clan patriarch Oscar M. Lopez current curatorial consultant Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez and writer (OML) welcomed an estimated 400 artists, journalists, culturati, Felice Sta. Maria, and edited by Purissima Benitez-Johannot, Group executives and family members in marking the jubilee of “Unfolding” chronicles the history of the museum and expounds what he described as “one of the legacies [of Eugenio H. Lopez on its collections that include Filipiniana titles, maps, artifacts, Sr.] that is closest to the Lopezes’ hearts.” He recalled the inaugu- and paintings by Filipino masters.