Simply Simply Sillifant Sillifant?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Oxford Democrat

The Oxford Democrat. NUMBER 24 VOLUME 80. SOUTH PARIS, MAINE, TUESDAY, JUNE 17, 1913. where hit the oat "Hear Hear The drearily. "That's you look out for that end of the business. to an extent. low Voted Out the Saloons called ye! ye! poll· D. *ΆΚΚ. increase the aupply quite They he said. on | are now closed." Everyone drew a aigb nail on the head," "Mouey. ▲11 I want you to do 1b to pass this AMONG THE FARMERS. Some Kansas experiment· show an in- The following extract from λ lettei Auctioneer, DON'T HURRY OR WORRY of and went borne to aopper, ex- the mean and dirty thing that can here note." Lictjnsed crease after a crop of clover was turned 'rom Mrs. Benj. H. Fiab of Santa Bar relief, — who ate theirs world—that's «"»«· At Meals Follows. TH* cept tbe election board, the best man In the "Colonel Tod hunter," replied tlie »IU>. Dyspepsia "SPKED PLOW." under. The yield of corn was Increased >ara, Calif., may be of interest bott whip âû0TH and oat of pail· and boxes, and afterwards Thurs." "the Indorsement and the col- Moderate- 20 bushel· an acre, oats 10 bushels, rom the temperance and tbe suffrage Colonel the trouble. banker, Tera» I went to A serene mental condition and time began counting votes. aleep other man's mon- a Correspondence on practical agricultural topics potatoes 30 bushel*. itand point. "Ifs generally the lateral make this note good, and it's to chow your food is more la bearing them count. thoroughly aollcHed. -

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

'Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War'

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Grant, P. and Hanna, E. (2014). Music and Remembrance. In: Lowe, D. and Joel, T. (Eds.), Remembering the First World War. (pp. 110-126). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9780415856287 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/16364/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘Music and Remembrance: Britain and the First World War’ Dr Peter Grant (City University, UK) & Dr Emma Hanna (U. of Greenwich, UK) Introduction In his research using a Mass Observation study, John Sloboda found that the most valued outcome people place on listening to music is the remembrance of past events.1 While music has been a relatively neglected area in our understanding of the cultural history and legacy of 1914-18, a number of historians are now examining the significance of the music produced both during and after the war.2 This chapter analyses the scope and variety of musical responses to the war, from the time of the war itself to the present, with reference to both ‘high’ and ‘popular’ music in Britain’s remembrance of the Great War. -

'Art of a Second Order': the First World War from the British Home Front Perspective

‘ART OF A SECOND ORDER’ The First World War From The British Home Front Perspective by RICHENDA M. ROBERTS A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham September 2012 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Little art-historical scholarship has been dedicated to fine art responding to the British home front during the First World War. Within pre-war British society concepts of sexual difference functioned to promote masculine authority. Nevertheless in Britain during wartime enlarged female employment alongside the presence of injured servicemen suggested feminine authority and masculine weakness, thereby temporarily destabilizing pre-war values. Adopting a socio-historical perspective, this thesis argues that artworks engaging with the home front have been largely excluded from art history because of partiality shown towards masculine authority within the matrices of British society. Furthermore, this situation has been supported by the writing of art history, which has, arguably, followed similar premise. -

Mud Blood and Futility RUAE

PASSAGE 1 The passage is taken from the introduction to Peter Parker’s book “The Last Veteran”, published in 2009. The book tells the life story of Harry Patch, who fought in the First World War, and eventually became the last surviving soldier to have fought in the trenches. He died in 2009, aged 111. Mud, Blood and Futility At 11 a.m. on Monday 11 November 1918, after four and quarter years in which howitzers boomed, shells screamed, machine guns rattled, rifles cracked, and the cries of the wounded and dying echoed across the battlefields of France and Belgium, everything suddenly fell quiet. A thick fog had descended that 5 morning and in the muffled landscape the stillness seemed almost palpable. For those left alive at the Front – a desolate landscape in which once bustling towns and villages had been reduced to piles of smoking rubble, and acre upon acre of woodland reduced to splintered and blackened stumps – there was little cause for rejoicing. The longed-for day had finally arrived but most 10 combatants were too enervated to enjoy it. In the great silence, some men were able to remember and reflect on what they had been through. Others simply felt lost. The war had swallowed them up: it occupied their every waking moment, just as it was to haunt their dreams in the future. There have been other wars since 1918 and in all of them combatants have 15 had to endure privation, discomfort, misery, the loss of comrades and appalling injuries. Even so, the First World War continues to exert a powerful grip upon our collective imagination. -

World War I Photography As Historical Record Kimberly Holifield University of Southern Mississippi

SLIS Connecting Volume 7 Article 9 Issue 1 SLIS Connecting Special Issue: British Studies 2018 Through the Lens: World War I Photography as Historical Record Kimberly Holifield University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting Part of the Archival Science Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, Scholarly Communication Commons, and the Scholarly Publishing Commons Recommended Citation Holifield, Kimberly (2018) "Through the Lens: World War I Photography as Historical Record," SLIS Connecting: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. DOI: 10.18785/slis.0701.09 Available at: https://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting/vol7/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in SLIS Connecting by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Through the Lens: World War I Photography as Historical Record By Kimberly Holifield British Studies Research Paper July 2016 Readers: Dr. Matthew Griffis Dr. Teresa Welsh Figure 1. Unidentified German Official Photographer in a Shallow Trench, June 1917 (Imperial War Museum Collection, www.iwm.org.uk) Figure 2. First World War Exhibit, Imperial War Museum (Holifield, 2016) “Photography takes an instant out of time, altering life by holding it still.”—Dorothea Lange Introduction However, a shift toward photography as historical Quotations fill vacant spaces along the walls of the record has slowly begun to make its way through the First World War exhibit at the Imperial War Museum world of scholarship. In their 2009 article, Tucker and of London. -

A Christmas Truce-Themed Assembly 53

TEACHING THE 1914 CHRISTMAS TRUCES Lesson, assembly and carol service plans to help RESOURCE PACK teachers commemorate the 1914 Christmas Truces for the centenary of World War 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Activity Plans Key Stage 3/4 31 How to use these resources 4 Creating Truce Images to the track of ‘Silent Night’ 32 Art / Music Introduction: A hopeful bit of history 6 Interrupting the War 34 The Martin Luther King Peace Committee 8 English / Creative Writing Christmas Truces Powerpoint: Information for Teachers 11 Christmas Truce Street Graffiti 37 Section 1: The War 12 Art Section 2: Opposing the War 13 Section 3: Combat and Trench Warfare 13 Research Local Participants via Letters to Newspapers 38 Section 4: The December 1914 Christmas Truces 14 History Activity Plans Key Stage 2/3 17 What’s the Point of Christmas Today? 40 Introduction to the Christmas Truces 18 RE / Ethics / PSE History / Moral Reflection Court Martial 41 Writing a Letter Home 20 History / Ethics / PSE English / History Overcoming Barbed Wire 44 Christmas Truces Game 22 Art P. E. Perceptions and Images of the Enemy 45 The Handshake 23 Art / PSE / History Art / Literacy Truce Words: Dominic McGill 46 Multi-session: Christmas Truce Re-enactment 24 Art History / P. E. / Ethics / Music / Languages / Drama Shared Elements of the Truces 47 Christmas Cakes for the Truces 26 Modern Languages Cookery Christianity and World War 1 48 Learning about Countries in 1914 28 RE / History / Ethics Geography The Christmas Gift 30 Fighting or Football 51 Art / Literacy History 2 A Christmas Truce-Themed Assembly 53 A School Carol Service 55 Appendices 60 Appendix 1: Images 60 Appendix 2: Eyewitness Testimonies 62 Appendix 3: Further Resources for Teachers 64 Appendix 4: Multi - Lingual Resources 65 3 HOW TO USE THESE RESOURCES The purpose of this pack is to provide teachers with concrete lesson plans as well as pointers and ideas for developing their own ways of bringing elements of the 1914 Christmas Truces to their schools’ programme between 2014 and 2018. -

220 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

220 bus time schedule & line map 220 Higher Crackington - Canworthy - Launceston View In Website Mode The 220 bus line (Higher Crackington - Canworthy - Launceston) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Higher Crackington: 12:38 PM (2) Launceston: 9:10 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 220 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 220 bus arriving. Direction: Higher Crackington 220 bus Time Schedule 31 stops Higher Crackington Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational Tesco, Launceston Tuesday 12:38 PM Launceston College, Launceston Wednesday Not Operational Hurdon Road, Scarne Industrial Estate Thursday Not Operational Launceston Hospital, Scarne Industrial Estate Friday Not Operational Pennygillam, Launceston Saturday Not Operational Western Road, Launceston St Johns Road, Launceston Western Road, Launceston 220 bus Info Direction: Higher Crackington Westgate Street, Launceston Stops: 31 Trip Duration: 80 min Westgate Street, Launceston Civil Parish Line Summary: Tesco, Launceston, Launceston Newport Industrial Estate Entrance, Newport College, Launceston, Hurdon Road, Scarne Industrial Estate, Launceston Hospital, Scarne Industrial St Thomas Road, Launceston Civil Parish Estate, Pennygillam, Launceston, St Johns Road, St Stephens Hill, Newport Launceston, Western Road, Launceston, Westgate Street, Launceston, Newport Industrial Estate Westbridge Road, Launceston Civil Parish Entrance, Newport, St Stephens Hill, Newport, Convent, Newport Convent, Newport, -

![[CORNWALL.] EGLOSKERRY. 24 POST OFFJC:G Crook Benjamin, Shopkeeper Haw Ken Edward, Farmer, Pendavey Salmon Richard, Jun](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4543/cornwall-egloskerry-24-post-offjc-g-crook-benjamin-shopkeeper-haw-ken-edward-farmer-pendavey-salmon-richard-jun-1094543.webp)

[CORNWALL.] EGLOSKERRY. 24 POST OFFJC:G Crook Benjamin, Shopkeeper Haw Ken Edward, Farmer, Pendavey Salmon Richard, Jun

[CORNWALL.] EGLOSKERRY. 24 POST OFFJC:g Crook Benjamin, shopkeeper Haw ken Edward, farmer, Pendavey Salmon Richard, jun. merchant, Sladea Davey John, farmer, Trenant Heath John, sen. carpenter, Cellars brid~e Derry Jame"', miller, Pencarrow mills cottage Snell Samuel, maltster Derry John, miller, Lemaile mill HendersonJohn,wooldealtn, Washaway Symons & Son,agems to WeF-t of Eng- Ellery John, mason, Perrcarrow J ewell John, blacksmith, Was ha way land life &. fire, & sub-distributor of Foale James 'Earl St. Vincent' Lander John, Ship inn, Wadebridge stamp3, Wadebridge Frazier James, tinplate worker MartynThomas, merchant, Wadebridge Symons Richard &. Son, solicitors, Gill James, farmer, Park Norway Edmund, merchant, Wadebrdg Wadebridge Greenwood John, Washateay inn, Pollard Edward, farmer, Court place West William, farmer, High croan Washaway Pollard Henry, fe~rmer, ClaJJper WiddenJspb.boot&shoema.Wadebrdg Gum mow John,' Ring of Bells' Pollard Samuel, solicitor, Wadebridge Willcocks George, farmer, Trevarnen Hawken Richard Lean, grocer&draper, Ripper John, tailor, Treguddick park Letters through Wadebrid:;re, which Wade bridge 1 Rowe J ames, farmer, Great Kelly is also the nearest money ordt'r office EG::LOSK.BR.R.Y, which is supposed to have derived its which is a large manor extending over the whole of the name from the church of St. Cyriacus, is a village and parish, and the manor house, now in the occupation of parish, 4l miles from Launceston, bounded by the parishes the incumbent, still remains. The estate of Tregeare is of North Petherwin, St. Stephen, St. Thomas, Trewen, partly in this parish, and partly in that of Laneast. Laneast, and Tresmere; it is in the Launcestou Union, There is a charity of £2 l2s. -

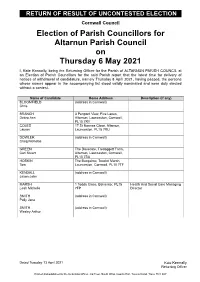

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

Oh What a Lovely War Program

OH WHAT A LOVELY WAR by Theatre Workshop, Charles Chilton and the members of the original cast Oh What a Lovely War was first performed at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, London on 19 March 1963. The idea for a chronicle of the First World War, told through the songs and documents of the time, was given flesh and blood in Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop, where every produc- tion was the fruit of close co-operation between writer, actor and director. The whole team participated in detailed research into the period and in the creative task of bringing their material to life in theatrical terms. There is one intermission of 15 minutes THE ‘SHARPSTERS’ COMPANY Kevin Bartz Anthony Vessels Bryan “Boots” Connolly Sean M. Cummings Willa Bograd Jeff Garland Sophia M. Guerrero-Murphy Dustin Harvey Kaitlyn Jaffke Will Lehnertz Holly Marks Roger Miller Kelly Oury Bryan C. Nydegger Leihoku Pedersen Jeff Schreiner Phoebe Piper Scott Sharp Meredith Salimbeni SONGS - ACT I Row, Row, Row – Company We Don’t Want To Lose You – Women Belgium Put the Kibosh on the Kaiser – Willa Bograd (& Kevin Bartz, Jeff Garland, Roger Miller) Are We Downhearted? – Kevin Bartz, Bryan “Boots” Connolly, Jeff Schreiner, Tony Vessels Hold Your Hand Out, Naughty Boy – Women I’ll Make A Man Of You – Leihoku Pedersen & Women We’re ‘ere Because We’re ‘ere – Kevin Bartz, Bryan “Boots” Connolly, Holly Marks, Roger Miller, Will Lehnertz, Jeff Schreiner, Anthony Vessels Pack Up Your Troubles – Kevin Bartz, Bryan “Boots” Connolly, Roger Miller, Will Lehnertz, Jeff Schreiner, Anthony Vessels Hitchy Koo – Kelly Oury & Jeff Schreiner (Dancer) Heilige Nacht – Kevin Bartz, Sean M. -

Researching Your Bristolian Ancestors in the First World War a Guide

RESEARCHING YOUR BRISTOLIAN ANCESTORS IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR A GUIDE BRISTOL 2014 IN ASSOCIATION WITH BRISTOL & AVON FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY WWW.BRISTOL2014.COM This guide to researching family history has been published as part of Bristol 2014, an extensive programme of activity marking the centenary of the start of the First World War. CONTENTS It has been researched and written by Eugene Byrne with the assistance of Geoff Gardiner of Bristol & Avon Family History Society. It is also available as a downloadable PDF from the Bristol 2014 website (www.bristol2014.com) along with a large-print version. Bristol 2014 is coordinated by Bristol Cultural Development Partnership. INTRODUCTION 5 The guide is provided free of charge thanks to the support of: THE BACKGROUND 6 Society of The First World War 6 Merchant Venturers Bristol’s Part in the War 8 The British Army in the First World War 10 Bristol’s Soldiers and Sailors 14 PREPARING TO RESEARCH 18 Rule 1: Find Out What You Already Have! 18 Thanks to Rebecca Clay, Ruth Hecht, Melanie Kelly, Amy O’Beirne, Sue Shephard, Zoe Steadman- Ideally You Need… 22 Milne and Glenys Wynne-Jones for proof-reading and commenting on drafts. What Am I Looking For? 23 Bristol 2014 is a partner in the First World War Partnership Programme (www.1914.org) RESEARCHING ONLINE 24 Starting Points 24 Genealogical Sites 24 War Diaries 25 Regimental Histories 26 Newspapers 26 Please note that Bristol 2014, Bristol Cultural Development Partnership and Bristol & Avon Family Women at War 27 History Society are not responsible for the content of external websites.