Interventions in Heritage Sacred Architecture After the Second

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Dubrovnik Manuscripts and Fragments Written In

Rozana Vojvoda DALMATIAN ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT AND BENEDICTINE SCRIPTORIA IN ZADAR, DUBROVNIK AND TROGIR PhD Dissertation in Medieval Studies (Supervisor: Béla Zsolt Szakács) Department of Medieval Studies Central European University BUDAPEST April 2011 CEU eTD Collection TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Studies of Beneventan script and accompanying illuminations: examples from North America, Canada, Italy, former Yugoslavia and Croatia .................................................................................. 7 1.2. Basic information on the Beneventan script - duration and geographical boundaries of the usage of the script, the origin and the development of the script, the Monte Cassino and Bari type of Beneventan script, dating the Beneventan manuscripts ................................................................... 15 1.3. The Beneventan script in Dalmatia - questions regarding the way the script was transmitted from Italy to Dalmatia ............................................................................................................................ 21 1.4. Dalmatian Benedictine scriptoria and the illumination of Dalmatian manuscripts written in Beneventan script – a proposed methodology for new research into the subject .............................. 24 2. ZADAR MANUSCRIPTS AND FRAGMENTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT ............ 28 2.1. Introduction -

Dalmatia Tourist Guide

Vuk Tvrtko Opa~i}: County of Split and Dalmatia . 4 Tourist Review: Publisher: GRAPHIS d.o.o. Maksimirska 88, Zagreb Tel./faks: (385 1) 2322-975 E-mail: [email protected] Editor-in-Chief: Elizabeta [unde Ivo Babi}: Editorial Committee: Zvonko Ben~i}, Smiljana [unde, Split in Emperor Diocletian's Palace . 6 Marilka Krajnovi}, Silvana Jaku{, fra Gabriel Juri{i}, Ton~i ^ori} Editorial Council: Mili Razovi}, Bo`o Sin~i}, Ivica Kova~evi}, Stjepanka Mar~i}, Ivo Babi}: Davor Glavina The historical heart of Trogir and its Art Director: Elizabeta [unde cathedral . 9 Photography Editor: Goran Morovi} Logo Design: @eljko Kozari} Layout and Proofing: GRAPHIS Language Editor: Marilka Krajnovi} Printed in: Croatian, English, Czech, and Gvido Piasevoli: German Pearls of central Dalmatia . 12 Translators: German – Irena Bad`ek-Zub~i} English – Katarina Bijeli}-Beti Czech – Alen Novosad Tourist Map: Ton~i ^ori} Printed by: Tiskara Mei}, Zagreb Cover page: Hvar Port, by Ivo Pervan Ivna Bu}an: Biblical Garden of Stomorija . 15 Published: annually This Review is sponsored by the Tourist Board of the County of Split and Dalmatia For the Tourist Board: Mili Razovi}, Director Prilaz bra}e Kaliterna 10, 21000 Split Gvido Piasevoli: Tel./faks: (385 21) 490-032, 490-033, 490-036 One flew over the tourists' nest . 18 Web: www.dalmacija.net E-mail: [email protected] We would like to thank to all our associates, tourist boards, hotels, and tourist agencies for cooperation. @eljko Kuluz: All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or repro- Fishing and fish stories . -

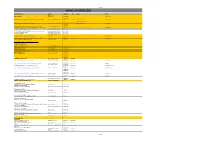

Grad Zagreb (01)

ADRESARI GRAD ZAGREB (01) NAZIV INSTITUCIJE ADRESA TELEFON FAX E-MAIL WWW Trg S. Radića 1 POGLAVARSTVO 10 000 Zagreb 01 611 1111 www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 GRADSKI URED ZA STRATEGIJSKO PLANIRANJE I RAZVOJ GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/II 01 610 1575 610-1292 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr [email protected] 01 658 5555 01 658 5609 GRADSKI URED ZA POLJOPRIVREDU I ŠUMARSTVO Zagreb, Avenija Dubrovnik 12/IV 01 658 5600 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 01 610 1169 GRADSKI URED ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE, ZAŠTITU OKOLIŠA, Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1168 IZGRADNJU GRADA, GRADITELJSTVO, KOMUNALNE POSLOVE I PROMET 01 610 1560 01 610 1173 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 1.ODJEL KOMUNALNOG REDARSTVA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 06 111 2.DEŽURNI KOMUNALNI REDAR (svaki dan i vikendom od 08,00-20,00 sati) Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 566 3. ODJEL ZA UREĐENJE GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 184 4. ODJEL ZA PROMET Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 111 Zagreb, Ulica Republike Austrije 01 610 1850 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE 18/prizemlje 01 610 1840 01 610 1881 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 485 1444 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA ZAŠTITU SPOMENIKA KULTURE I PRIRODE Zagreb, Kuševićeva 2/II 01 610 1970 01 610 1896 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA JAVNO ZDRAVSTVO Zagreb, Mirogojska 16 01 469 6111 INSPEKCIJSKE SLUŽBE-PODRUČNE JEDINICE ZAGREB: 1)GRAĐEVINSKA INSPEKCIJA 2)URBANISTIČKA INSPEKCIJA 3)VODOPRAVNA INSPEKCIJA 4)INSPEKCIJA ZAŠTITE OKOLIŠA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1111 SANITARNA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Šubićeva 38 01 658 5333 ŠUMARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Zapoljska 1 01 610 0235 RUDARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Ul Grada Vukovara 78 01 610 0223 VETERINARSKO HIGIJENSKI SERVIS Zagreb, Heinzelova 6 01 244 1363 HRVATSKE ŠUME UPRAVA ŠUMA ZAGREB Zagreb, Kosirnikova 37b 01 376 8548 01 6503 111 01 6503 154 01 6503 152 01 6503 153 01 ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING d.o.o. -

Belgrade - Budapest - Ljubljana - Zagreb Sample Prospect

NOVI SAD BEOGRAD Železnička 23a Kraljice Natalije 78 PRODAJA: PRODAJA: 021/422-324, 021/422-325 (fax) 011/3616-046 [email protected] [email protected] KOMERCIJALA: KOMERCIJALA 021/661-07-07 011/3616-047 [email protected] [email protected] FINANSIJE: [email protected] LICENCA: OTP 293/2010 od 17.02.2010. www.grandtours.rs BELGRADE - BUDAPEST - LJUBLJANA - ZAGREB SAMPLE PROSPECT 1st day – BELGRADE The group is landing in Serbia after which they get on the bus and head to the downtown Belgrade. Sightseeing of the Belgrade: National Theatre, House of National Assembly, Patriarchy of Serbian Orthodox Church etc. Upon request of the group, Tour of The Saint Sava Temple could be organized. The tour of Kalemegdan fortress, one of the biggest fortress that sits on the confluence of Danube and Sava rivers. Upon request of the group, Avala Tower visit could be organized, which offers a view of mountainous Serbia on one side and plain Serbia on the other. Departure for the hotel. Dinner. Overnight stay. 2nd day - BELGRADE - NOVI SAD – BELGRADE Breakfast. After the breakfast the group would travel to Novi Sad, consider by many as one of the most beautiful cities in Serbia. Touring the downtown's main streets (Zmaj Jovina & Danube street), Danube park, Petrovaradin Fortress. The trip would continue towards Sremski Karlovci, a beautiful historic place close to the city of Novi Sad. Great lunch/dinner option in Sremski Karlovci right next to the Danube river. After the dinner, the group would head back to the hotel in Belgrade. -

Water Supply System of Diocletian's Palace in Split - Croatia

Water supply system of Diocletian's palace ın Split - Croatia K. Marasović1, S. Perojević2 and J. Margeta 3 1University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering Architecture and Geodesy 21000 Split, Matice Hrvatske 15, Croatia; [email protected]; phone : +385 21 360082; fax: +385 21 360082 2University of Zagreb, Faculty of Architecture, Mediterranean centre for built heritage 21000 Split, Bosanska 4, Croatia; [email protected]; phone : +385 21 360082; fax: +385 21 360082 3University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering Architecture and Geodesy 21000 Split, Matice Hrvatske 15, Croatia; [email protected]; phone : +385 21 399073; fax: +385 21 465117 Abstract Roman water supply buildings are a good example for exploring the needs and development of infrastructure necessary for sustainable living in urban areas. Studying and reconstructing historical systems contributes not only to the preservation of historical buildings and development of tourism but also to the culture of living and development of hydrotechnical profession. This paper presents the water supply system of Diocletian's Palace in Split. It describes the 9.5 km long Roman aqueduct, built at the turn of 3rd century AD. It was thoroughly reconstructed in the late 19th century and is still used for water supply of the city of Split. The fact that the structure was built 17 centuries ago and is still technologically acceptable for water supply, speaks of the high level of engineering knowledge of Roman builders. In the presentation of this structure this paper not only departs from its historical features, but also strives to present its technological features and the possible construction technology. -

Accommodations. See Also

16_598988 bindex.qxp 3/28/06 7:16 PM Page 332 Index See also Accommodations index, below. Autocamp Jezevac (near Krk B.P. Club (Zagreb), 258 Accommodations. See also Town), 179 Brac, 97–102 Accommodations Index Autocamp Kalac, 112 Brace Radic Trg (Vocni Trg or best, 3–4 Autocamp Kovacine (Cres), 187 Fruit Square; Split), 84 private, 37 Autocamp Solitudo Branimir Center (Zagreb), 256 surfing for, 25–26 (Dubrovnik), 58 Branimirova Ulica, graffiti wall tips on, 36–38 Autocamp Stoja (Pula), 197 along (Zagreb), 253 Activatravel Istra (Pula), 194 Branislav-Deskovi5 Modern Art Airfares, 25 Gallery (Bol), 99 Airlines, 29, 34 Babi5 wine, 156 Brela, 94 Airport security, 29–30 Babin Kuk (Dubrovnik), 50 Bridge Gate (Zadar), 138 Algoritam (Zagreb), Balbi Arch (Rovinj), 205 Brijuni Archipelago (Brioni), 233, 255–256 Banje (Dubrovnik), 57 201–202 Allegra Arcotel (Zagreb), 257 Baptistry (Temple of Jupiter; Bronze Gate (Split), 82 American Express/ Split), 81–82 Bunari Secrets of Sibenik, 153 Atlas Travel, 38 Baredine Cave, 212 Burglars’ Tower (Kula Lotrs5ak; Dubrovnik, 49 Bars, Zagreb, 257–258 Zagreb), 251 Split, 78 Baska (Krk Island), 5, 176, 180 Business hours, 38 traveler’s checks, 15 Baska Tablet (Zagreb), 202, 252 Bus travel, 34 Zagreb, 232 Beaches. See also specific Buzet, 219, 225–227 Aquanaut Diving (Brela), 95 beaches Aquarium best, 5 and Maritime Museum Hvar Town, 105 Caesarea Gate (Salona), 93 (Dubrovnik), 52–53 Makarska Riviera, 94–95 Calvary Hill (Marija Bistrica), 274 Porec, 212 Pag Island, 129 Camping, 37 Rovinj, 206 Beli, 186 Autocamp -

Ultimate Self-Drive Croatia & Slovenia

Ultimate Self-Drive Croatia & Slovenia A Private, Historical and Cultural Self-Drive Tour of Zagreb through to Dubrovnik with private Exeter guides opening doors along the way Exeter International White Glove Self-Drive Program Includes: A pre-programmed GPS system for you to use while in Europe. 24-hour local help line available to you as you travel and manned exclusively by Exeter local staff. Our expert advice in finding the perfect car for your trip. The freedom to deviate and explore on your own and then jump back into your planned itinerary at any time. Day 1 Arrival in Zagreb, Croatia Day 2 Zagreb Day 3 Zagreb ---- Bled & Bohinj ---- Rovinj Day 4 Rovinj ---- I s t r i a ---- Rovinj Day 5 Rovinj ---- P u l a ---- Rovinj Day 6 Rovinj ---- Split Day 7 Split Day 8 Split ---- H v a r ---- Split Day 9 Split ---- Dubrovnik Day 10 Dubrovnik Day 11 Dubrovnik ---- Montenegro ---- Dubrovnik Day 12 Departure from Dubrovnik Why Exeter International? At Exeter International we have been creating memories and crafting our trademark extraordinary journeys to Central Europe, Russia and Central Asia for 23 years. Our specialty is to distil the best of the best in iconic places that are on so many people’s travel must do list. We are not a call center of nameless, faceless people. We do not try to be everything to everyone. We are small team of specialists. We are all committed to providing the best travel experiences to our destinations. Each member of our team has travelled extensively throughout our destinations, giving them insider knowledge lacking in many other tour operators. -

Poland, Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Croatia & Medjugorje

Poland, Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, Croatia & Medjugorje Warsaw, Krakow, Wadowice, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Zagreb, Medjugorje Day 1 – Depart U.S.A Day 9 – Vienna - Budapest Day 2 –Arrive Warsaw This morning we drive to Budapest, the capital of Hungary. Our sightseeing tour includes the older section: Buda, located on the right bank of the Day 3 – Warsaw - Niepokalanow - Czestochowa - Krakow Danube River, where the Royal Castle, the Cathedral of St. Matthew After a panoramic tour of Warsaw, we depart to Niepokalanow, home of and Fisherman’s Bastion can be found. Enjoy views of the Neo-Gothic the Basilica of the Virgin Mary, and a Franciscan monastery founded by St. Parliament, Hero’s Square and the Basilica of St. Stephen. Maximilian Kolbe. On to Czestochowa to visit Jasna Gora Monastery and see the Black Madonna at the Gothic Chapel of Our Lady. Day 10 – Budapest - Marija Bistrica - Zagreb Depart Budapest to Zagreb. En route we stop to visit the brilliant and Day 4 – Krakow - Lagiewniki - Wieliczka spectacular sanctuary of Our Lady of Marija Bistrica, the national Shrine of Our morning tour will include visits to Wawel Hill, the Royal Chambers Croatia and home to the miraculous statue of the Virgin Mary. and Cathedral. Then walk along Kanonicza Street, where Pope John Paul II resided while living in Krakow, then to the Mariacki Church and the Market Day 11 – Zagreb - Split - Medjugorje Square. We will spend the afternoon at the Lagiewniki “Divine Mercy In the morning we depart Zagreb to Medjugorje. En route we stop in Split Shrine” to visit the Shrine’s grounds and Basilica. -

Athens to Venice, Venice to Athens

STAR CLIPPERS SHORE EXCURSIONS Athens to Venice : Athens - Mykonos – Santorin – Katakolon - Corfu – Kotor – Dubrovnik – Korcula - Hvar - Cres - Venice Venice to Athens : Venice - Cres - Hvar - Dubrovnik – Kotor – Corfu – Katakolon - Santorin – Mykonos – Athens All tours are offered with English speaking guides. The length of the tours and time spent on the sites is given as an indication as it may vary depending on the road, weather, sea and traffic conditions and on the group’s pace. Minimum number of participants indicated per coach or group. Walking tours in Croatia can only be guided in one language. The level of physical fitness required for our activities is given as a very general indication without any knowledge of our passenger’s individual abilities. Broadly speaking to enjoy activities such as hiking, biking, snorkelling, boating or other activities involving physical exertion, passengers should be fit and active. Passengers must judge for themselves whether they will be capable of participating in and above all enjoying such activities. STAR CLIPPERS SHORE EXCURSIONS All information concerning excursions is correct at the time of printing. However Star Clippers reserves the right to make changes, which will be relayed to passengers during the Cruise Director’s onboard information sessions Excursion prices quoted may vary if entrance fees to sites and VAT increase in 2021. STAR CLIPPERS SHORE EXCURSIONS CROATIA CRES The best way to experience the city is to stroll through the Old Town. Here you will find a typically Medieval atmosphere with tall narrow buildings huddling together and a maze of winding streets. Emblems on the house fronts and doors indicate the trades of their former inhabitants – farm labourer, blacksmith, fisherman etc. -

Egypt in Croatia Croatian Fascination with Ancient Egypt from Antiquity to Modern Times

Egypt in Croatia Croatian fascination with ancient Egypt from antiquity to modern times Mladen Tomorad, Sanda Kočevar, Zorana Jurić Šabić, Sabina Kaštelančić, Marina Kovač, Marina Bagarić, Vanja Brdar Mustapić and Vesna Lovrić Plantić edited by Mladen Tomorad Archaeopress Egyptology 24 Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-339-3 ISBN 978-1-78969-340-9 (e-Pdf) © Authors and Archaeopress 2019 Cover: Black granite sphinx. In situ, peristyle of Diocletian’s Palace, Split. © Mladen Tomorad. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Preface ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������xiii Chapter I: Ancient Egyptian Culture in Croatia in Antiquity Early Penetration of Ancient Egyptian Artefacts and Aegyptiaca (7th–1st Centuries BCE) ..................................1 Mladen Tomorad Diffusion of Ancient Egyptian Cults in Istria and Illyricum (Late 1st – 4th Centuries BCE) ................................15 Mladen Tomorad Possible Sanctuaries of Isaic Cults in Croatia ...................................................................................................................26 -

The Rise of Bulgarian Nationalism and Russia's Influence Upon It

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it. Lin Wenshuang University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wenshuang, Lin, "The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1548 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Lin Wenshuang All Rights Reserved THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Approved on April 1, 2014 By the following Dissertation Committee __________________________________ Prof.