The Longterm Effect of Lockouts on Alcoholrelated Emergency Department Attendances Within Ballarat, Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Report Introduction

Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Report Introduction Launceston and Canberra have scooped the pool as Australia’s most family friendly cities, bumping Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane to 14th, 23rd and 24th positions respectively, according to a study into the family friendliness of the nation’s 30 largest cities. The inaugural Suncorp Bank Family Friendly Index shows that half of the top 10 family friendly cities are not state or territory capitals and instead include the smaller, regional cities of Albury/Wodonga, Toowoomba, and Launceston. The report finds that crowded, stressful, urban jungles and under serviced Eastern seaboard capitals are being upstaged by regional towns as the most family friendly cities in Australia. The inaugural Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Index monitors the most populated 30 cities in Australia and ranks them according to which city is the most family friendly across 10 key indicators. The indicators themselves are divided into two categories; Primary and Secondary. Primary indicators refer to those indicators that have a larger bearing on a city’s ‘livability’, (such as, crime education and housing) as such these indicators are weighted double that of the secondary indicators. While the Index analyses indicators such as Education, Crime, Health, Income, Unemployment and Connectivity, some notable omissions include Environment (climate and weather), Lifestyle (beaches and parks) which have not been included due to their subjective nature and a lack of consistent data for each of the 30 cities analysed. Methodology To derive the rankings for the Suncorp Bank Family Friendly City Index each city was systematically ranked on each of the 10 indicators. -

International Course Guide 2022

International Course Guide 2022 01 Federation University Australia acknowledges Wimmera Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia, Jupagulk the Traditional Custodians of the lands and waters where our campuses, centres and field Ballarat Wadawurrung stations are located and we pay our respects to Elders past and present. We extend this Berwick Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri respect to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and First Nations Peoples. Gippsland Gunai Kurnai The Aboriginal Traditional Custodians of the Nanya Station Mutthi Mutthi and Barkindji lands and waters where our campuses, centres and field stations are located include: Brisbane Turrbal and Jagera At Federation University, we’re driven to make a real difference. To the lives of every student who Federation University 01 Education and Early Childhood 36 walks through our doors, and to the communities Reasons to choose Federation University 03 Engineering 42 Find out where you belong 05 Health 48 we help build and are proud to be part of. Regional and city living 06 Humanities, Social Sciences, Criminology We are one of Australia’s oldest universities, known today and Social Work 52 Our campuses and locations 08 for our modern approach to teaching and learning. For 150 years Information Technology 56 we have been reaching out to new communities, steadily building Industry connections 12 Performing Arts, Visual Arts and Design 60 a generation of independent thinkers united in the knowledge Student accommodation 14 that they are greater together. Psychology 62 Our support services and programs 16 Science 64 Be part of our diverse community International Student Support 18 Sport, Health, Physical and Outdoor Education 66 Today, we are proud to have more than 21,000 Australian Experience uni life 19 and international students and 114,000 alumni across Australia Higher Degrees by Research 68 Study abroad and exchange 20 and the world. -

Settlement Engagement and Transition Support (SETS)

Settlement Engagement and Transition Support (SETS) - Successful Applicants Note: The final list of providers is subject to Funding Agreement negotiations with successful applicants. State/Territory of LEGAL ENTITY NAME Service Area/s Service Area/s Client Services Access Community Services Ltd QLD Gold Coast, Ipswich, Logan - Beaudesert African Women's Federation of SA Inc SA Adelaide - North, Adelaide - South, Adelaide - West Albury-Wodonga Volunteer Resource Bureau Inc NSW & VIC Albury (NSW), Wodonga (VIC) Anglicare N.T. Ltd NT Darwin Anglicare SA Ltd SA Adelaide - North Arabic Welfare Inc VIC Brunswick - Coburg, Moreland - North, Tullamarine - Broadmeadows, Whittlesea - Wallan Asian Women at Work Inc NSW Auburn, Bankstown, Blacktown, Canterbury, Fairfield, Hurstville Assyrian Australian Association NSW Blacktown, Ryde, Sydney South West Australian Afghan Hassanian Youth Association Inc NSW NSW Australian Muslim Women's Centre for Human Rights Inc VIC Melbourne - Inner, Melbourne - North East, Melbourne - North West, Melbourne - South East, Melbourne - West Australian Refugee Association Inc SA Adelaide - Central and Hills, Adelaide - North, Adelaide - South, Adelaide - West Ballarat Community Health VIC Ararat Region, Ararat, Ballarat Bendigo Community Health Services Ltd VIC Bendigo Brisbane South Division Ltd QLD Brisbane - East, Brisbane - North, Brisbane - South, Brisbane - West, Brisbane - Inner City Bundaberg & District Neighbourhood Centre Inc QLD Bundaberg CatholicCare Victoria Tasmania VIC & TAS TAS: Hobart VIC: Melbourne -

BENDIGO EC U 0 10 Km

Lake Yando Pyramid Hill Murphy Swamp July 2018 N Lake Lyndger Moama Boort MAP OF THE FEDERAL Little Lake Boort Lake BoortELECTORAL DIVISION OF Echuca Woolshed Swamp MITIAMO RD H CA BENDIGO EC U 0 10 km Strathallan Y RD W Prairie H L O Milloo CAMPASPE D D I D M O A RD N Timmering R Korong Vale Y P Rochester Lo d d o n V Wedderburn A Tandarra N L R Greens Lake L E E M H IDLAND Y ek T HWY Cre R O Corop BENDIGO Kamarooka East N R Elmore Lake Cooper i LODDON v s N H r e W e O r Y y r Glenalbyn S M e Y v i Kurting N R N E T Bridgewater on Y Inglewood O W H Loddon G N I Goornong O D e R N D N p C E T A LA s L B ID a H D M p MALLEE E E R m R Derby a Huntly N NICHOLLS Bagshot C H Arnold Leichardt W H Y GREATER BENDIGO W Y WIMM Marong Llanelly ERA HWY Moliagul Newbridge Bendigo M Murphys CIVOR Tarnagulla H Creek WY Redcastle STRATHBOGIE Strathfieldsaye Knowsley Laanecoorie Reservoir Lockwood Shelbourne South Derrinal Dunolly Eddington Bromley Ravenswood BENDIGO Lake Eppalock Heathcote Tullaroop Creek Ravenswood South Argyle C Heathcote South A L D locality boundary E Harcourt R CENTRAL GOLDFIELDS Maldon Cairn Curran Dairy Flat Road Reservoir MOUNT ALEXANDER Redesdale Maryborough PYRENEES Tooborac Castlemaine MITCHELL Carisbrook HW F Y W Y Moolort Joyces Creek Campbells Chewton Elphinstone J Creek Pyalong o Newstead y c Strathlea e s Taradale Talbot Benloch locality MACEDON Malmsbury boundary Caralulup C RANGES re k ek e re Redesdale Junction C o Kyneton Pastoria locality boundary o r a BALLARAT g Lancefield n a Clunes HEPBURN K Woodend Pipers Creek -

ACU Undergraduate Course Guide 2021

Undergraduate Course Guide 2021 AUSTRALIAN CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY Madeleine ACU student You first. Success next. Celebrating 30 years 1990 – 2020 Contents 02 Course area index 04 Think you know ACU? You’re just getting started 06 Numbers that count 08 Our campuses 10 Life at ACU 12 Go global 14 See the world through the eyes of others 17 Course information 107 Applying to ACU 108 Pathways to ACU 110 Entry programs 113 Fees and scholarships 114 Uni terminology 116 Selection rank guide 116 Course directory Course area index PAGE COURSE AREA PAGE COURSE AREA PAGE COURSE AREA A D E 49 Laws/commerce 23 Accounting and nance 86 Early childhood education (birth to 50 Laws/global studies ve years) 76 Applied public health 51 Laws/philosophy 88 Education (early childhood and 63 Applied public health/ primary) 52 Laws/psychological science biomedical science 98 Education (fourth year upgrade) 53 Laws/theology 76 Applied public health/ business administration 91 Education (primary and secondary) 39 Liberal arts 79 Applied public health/exercise science 90 Education (primary and special M education) 32 Applied public health/global studies 55 Midwifery 89 Education (primary) 38 Arts 55 Midwifery (graduate entry) 93 Education (secondary and special N 95 Arts (humanities)/education education) (secondary) 56 Nursing 92 Education (secondary) 95 Arts (mathematics)/education 57 Nursing (enrolled nurses) (secondary) 94 Education (secondary)/arts 58 Nursing/business administration 95 Arts (technology)/education 95 Education (secondary)/arts (secondary) (humanities) -

Geelong Ballarat Bendigo Gippsland Western Victoria Northern Victoria

Project Title Council Area Grant Support GEELONG Growth Areas Transport Infrastructure Strategy Greater Geelong (C) $50,000 $50,000 Stormwater Service Strategy Greater Geelong (C) $100,000 Bannockburn South West Precinct Golden Plains (S) $60,000 $40,000 BALLARAT Ballarat Long Term Growth Options Ballarat (C) $25,000 $25,000 Bakery Hill Urban Renewal Project Ballarat (C) $150,000 Latrobe Street Saleyards Urban Renewal Ballarat (C) $60,000 BENDIGO Unlocking Greater Bendigo's potential Greater Bendigo (C) $130,000 $135,000 GIPPSLAND Wonthaggi North East PSP and DCP Bass Coast (S) $25,000 Developer Contributions Plan - 5 Year Review Baw Baw (S) $85,000 South East Traralgon Precinct Structure Plan Latrobe (C) $50,000 West Sale Industrial Area - Technical reports Wellington (S) $80,000 WESTERN VICTORIA Ararat in Transition - an action plan Ararat (S) $35,000 Portland Industrial Land Strategy Glenelg (S) $40,000 $15,000 Mortlake Industrial Land Supply Moyne (S) $75,000 $25,000 Southern Hamilton Central Activation Master Plan $90,000 Grampians (S) Allansford Strategic Framework Plan Warrnambool (C) $30,000 Parwan Employment Precinct Moorabool (S) $100,000 $133,263 NORTHERN VICTORIA Echuca West Precinct Structure Plan Campaspe (S) $50,000 Yarrawonga Framework Plan Moira (S) $50,000 $40,000 Shepparton Regional Health and Tertiary Grt. Shepparton (C) $30,000 $30,000 Education Hub Structure Plan (Shepparton) Broadford Structure Plan – Investigation Areas Mitchell (S) $50,000 Review Seymour Urban Renewal Precinct Mitchell (S) $50,000 Benalla Urban -

Classroom Code Classroom Venues Address Suburb Postcode

Classroom Code Classroom Venues Address Suburb Postcode AFL Victoria Sports Development Program AFLDAND AFL Dandenong Dandenong Oasis, Heatherton Road & Cleeland St Dandenong 3175 AFLBURW AFL Burwood Nunawading Basketball Stadium, East Burwood Reserve, Burwood Highway, East Burwood 3151 AFLCACLAY AFL/Cricket Clayton Meade Reserve, Haughton Road, Clayton 3168 AFLFRANK AFL Frankston Frankston Football Club, Plowman Place, Frankston 3199 AFLGEEL AFL Geelong East Geelong Football Club, Richmond Oval, Richmond Crescent, East Geelong 3219 AFLPRES AFL Preston Northern Blues Football Club, Preston City Oval, Cramer Street, Preston 3072 AFLSTRA AFL Strathmore Syd McGain Oval, Lebanon Reserve, Mascoma Street, Strathmore 3041 AFLSUN AFL Sunshine Albion Football Club, Keith Miller Oval, JR Parsons Reserve, Stanford St, Sunshine 3020 AFLWER AFL Werribee Soldiers Reserve, Corner Duncans Road and College Road, Werribee 3030 MULTBALL Multi Ballarat East Point FNC, Eastern Oval, 211 Peel Street North, Ballarat 3350 MULTBEN Multi Bendigo South Bendigo FNC, Queen Elizabeth Oval, Cnr View and Barnard St, Bendigo 3550 MULTSHEPP Multi Shepparton Deakin Reserve, Cnr Harold and Nixon Street, Shepparton 3630 MULTITRA Multi Traralgon Traralgon Recreation Reserve, Whittakers Road, Traralgon 3844 AFL Victoria High Performance Program AFLVICHPP AFL Victoria HPP Program Northern Pavilion, Princess Park, 360 Royal Parade, Carlton 3058 Aquatics Sports Development Program AQTVALB Aquatics/Tennis Albert Park Albert Sailing Club, Aquatic Drive, Albert Park Lake, Albert -

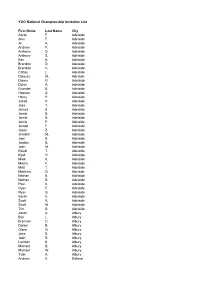

First Name Last Name City Aaron F. Adelaide Alex F. Adelaide Ali A. Adelaide Andrew P. Adelaide Anthony D. Adelaide Anthony S. Adelaide Ben A

YGO National Championship Invitation List First Name Last Name City Aaron F. Adelaide Alex F. Adelaide Ali A. Adelaide Andrew P. Adelaide Anthony D. Adelaide Anthony S. Adelaide Ben A. Adelaide Brandon D. Adelaide Brendan C. Adelaide Chhay L. Adelaide Daisuke M. Adelaide Danny O. Adelaide Dylan A. Adelaide Evander B. Adelaide Hassan A. Adelaide Henry P. Adelaide Jacob P. Adelaide Jake T. Adelaide James B. Adelaide Jamie B. Adelaide Jamie B. Adelaide Jamie F. Adelaide Jarrad F. Adelaide Jason Z. Adelaide Jennifer M. Adelaide Joel B. Adelaide Jordan B. Adelaide Josh M. Adelaide Kaleb T. Adelaide Kyall H. Adelaide Mark K. Adelaide Martin F. Adelaide Matt T. Adelaide Matthew D. Adelaide Nathan B. Adelaide Nathan S. Adelaide Paul K. Adelaide Ryan F. Adelaide Ryan G. Adelaide Sarah V. Adelaide Scott K. Adelaide Scott M. Adelaide Tim B. Adelaide Aaron A. Albury Ben L. Albury Brennan C. Albury Daniel B. Albury Glenn H. Albury Jake B. Albury Josh S. Albury Lachlan B. Albury Michael B. Albury Michael W. Albury Tyler A. Albury Andrew K. Ballarat Anthony H. Ballarat Ben S. Ballarat Joel W. Ballarat Luke M. Ballarat Matt H. Ballarat Matt L. Ballarat Stuart B. Ballarat Toby N. Ballarat Kurt W. Brisbane Aaron H. Brisbane Andrew B. Brisbane Andrew C. Brisbane Andrew W. Brisbane Arden O. Brisbane Ashley W. Brisbane Ben G. Brisbane Bradley N. Brisbane Calos C. Brisbane Chris D. Brisbane Chris H. Brisbane Chris H. Brisbane Daniel B. Brisbane Daniel W. Brisbane Darni N. Brisbane Dave A. Brisbane Dave G. Brisbane Dion R. Brisbane Douglas A. Brisbane Dylan A. -

ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA HORSHAM, BALLARAT & GEELONG Bus Time Schedule & Line Map

ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA HORSHAM, BALLARAT & GEELONG bus time schedule & line map ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA H… Adelaide View In Website Mode The ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA HORSHAM, BALLARAT & GEELONG bus line (Adelaide) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Adelaide: 7:40 AM - 5:54 PM (2) Melbourne: 6:00 AM - 3:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA HORSHAM, BALLARAT & GEELONG bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA HORSHAM, BALLARAT & GEELONG bus arriving. Direction: Adelaide ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA HORSHAM, 14 stops BALLARAT & GEELONG bus Time Schedule VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Adelaide Route Timetable: Sunday 10:23 AM - 8:23 PM Geelong Station/Railway Tce (Geelong) Monday 7:40 AM - 5:54 PM 195 Latrobe Terrace, Geelong Tuesday 7:40 AM - 5:54 PM Calvert St/Ballarat Rd (Hamlyn Heights) 96 Ballarat Road, Hamlyn Heights Wednesday 7:40 AM - 5:54 PM River St/Midland Hwy (Batesford) Thursday 7:40 AM - 5:54 PM 1-5 River Street, Batesford Friday 7:40 AM - 9:25 PM Ryan Rd/Midland Hwy (Gheringhap) Saturday 8:18 AM - 5:43 PM 1279 Midland Highway, Gheringhap Mcphillips Rd/High St (Bannockburn) High Street, Bannockburn ADELAIDE - MELBOURNE VIA HORSHAM, General Store/Midland Hwy (Lethbridge) BALLARAT & GEELONG bus Info 2 Russell Street, Lethbridge Direction: Adelaide Stops: 14 Lawler St/Midland Hwy (Meredith) Trip Duration: 90 min 23 Wallace Street, Meredith Line Summary: Geelong Station/Railway Tce (Geelong), Calvert St/Ballarat Rd (Hamlyn Heights), General Store/Midland -

14-15Art Gallery of Ballarat Annual Report

Art Gallery of Ballarat Annual Report 14-15 Annual Report 2014-15 Chair’s Report 4 Director’s Report 8 Association Report 10 Gallery Guides Report 12 Acquisitions 14 Adopt an Artwork 26 Donations, Gifts, and Bequests 27 Exhibitions 28 EIKŌN: Icons of the Orthodox Christian World 30 Touring Exhibitions 32 Outward Loans 34 Publications & Merchandise 36 Education Report 38 Public Programs 40 ISSN 0726-5530 Gallery Staff and Volunteers 49 Art Gallery of Ballarat Board Members 50 ACN: 145 246 224 ABN: 28 145 246 224 Budget Summaries 52 40 Lydiard Street North Ballarat Victoria 3350 T 03 5320 5858 F 03 5320 5791 [email protected] www.artgalleryofballarat.com.au Image right: installation view of EIKŌN: Icons of the Orthodox Christian World Image next page: Hugh DT Williamson Gallery Vision The Art Gallery of Ballarat where Art Inspires, Stimulates and Challenges Mission To foster and enrich the cultural life of our city, our region and the Nation by acquiring, conserving and presenting a great collection of art. Image: installation view of Art and Australia 2003 – 2013 3 Chair’s Report Art Gallery of Ballarat Board of Directors I often tell people that the Art Gallery of Ballarat is about a city wide program around the exhibition, including withdrawal of our café proprietors early this year allowed us art: we buy it, we show it, we lend it and we store it. The launching the Season of the Arts Program. The Archibald to trial The Salon, a relaxed meeting area, which has been challenge for us is how to do this in a creative and inspiring Prize 15-16 Exhibitions and the Art Gallery of Ballarat major very popular with Association Members, staff and visitors. -

Bendigo - Climate Analogue Town for Ballarat for the Year 2090

Bendigo - Climate Analogue Town for Ballarat for the Year 2090 Based on the maximum consensus of models based on CMIP5 for the year 2090 and a high emissions scenario, (RCP 8.5). Information developed using the CSIRO Bendigo (North Central Victoria) Climate Change in Australia Analogue Explorer Tool Image: Mark Imhof Image: Mark Imhof Mean Max. Temperature C0 Mean rainfall (mm) Season Ballarat Ballarat Bendigo Ballarat Ballarat Bendigo (current) (projected (current) (current) (projected (current) 2090)* 2090)* Spring 16.7 20.5 21.2 202.7 154.5 145.9 Bendigo Summer 24.2 28.0 30.3 136.2 123.3 98.5 Ballarat Autumn 18.3 21.9 22.5 142.6 144.3 107.9 Winter 11.0 14.0 13.8 208.2 189.7 177.8 17.6 689.7 530.1 ANNUAL 21.1 22.0 611.8 Image: Jen Clarke Ballarat (Central Victoria) Image: Mark Imhof Image: Mark Imhof Image: Jim Burgess Image: Powercor *This analogue has been further refined to include projected seasonal changes. It assumes an average rainfall decline across the Southern Slopes Region of 11% and average temp. increase of 3.5 C 0, based on data from the Climate Futures Tool . For Bendigo, mean spring & summer temp. is within +/-1oC and rainfall across all seasons is within +/-15% respectively of this future scenario for Ballarat. Analogue Logic: Information above was developed using the CSIRO Climate Change in Australia Analogue Explorer Tool * The above analogue is based on the average annual rainfall and temperature in the year 2090, maximum consensus of models (CMIP5) and a high emissions scenario (RCP 8.5). -

19. Liberty Square

19. Liberty Square Liberty Square was named by the Darwin Town Council in June 1919 to commemorate the ‘Darwin Rebellion’ of 17 December 1918. That rebellion, which culminated in a protest directed at Government House by hundreds of workers on this site, and the unrest leading to it, resulted in a 1919 Royal Commission into the Administration of the Northern Territory conducted by Justice Norman Kirkwood Ewing (1870-1928). On the western side of Liberty Square is a memorial cairn at the place where the sub-sea cable from Banjowangie (Banyuwangi) Indonesia was joined with the Overland Telegraph Line to revolutionise communications in Australia on 20 November 1871. Towards the eastern side is a plinth and plaque commemorating the scientific achievement of Pietro ‘Commendatore’ Baracchi who, in collaboration with colleagues in Singapore and Banjowangie, established true longitude of Port Darwin and other Australian colonial and New Zealand capital cities in 1883 in the grounds of the Port Darwin Post Office and Telegraphic Station (now Parliament House). On the eastern side near the Supreme Court is a Banyan tree, which is valued by the community as a remnant of the original Darwin foreshore vegetation. It is over 200 years old and was the congregation point for Larrakia youths prior to ceremonies that took place under the nearby Tamarind tree. Liberty Square was the site for the original Darwin Cenotaph, which is now located on the old Darwin Oval on the Esplanade. History Sub-sea Telegraph Cables From the 1850s telegraph technology was very quickly taken up by the Australian colonies, building networks across their own territories, and then soon connecting to each other.