Reply Evidence on Behalf of Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pipeline Authority Annual Report 2018

North Dakota Pipeline Authority Annual Report July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018 Industrial Commission of North Dakota Governor Doug Burgum, Chairman Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem Agriculture Commissioner Doug Goehring North Dakota Pipeline Authority Annual Report July 1, 2017 – June 30, 2018 Overview At the request of the North Dakota Industrial Commission, the Sixtieth Legislature passed House Bill 1128 authorizing the North Dakota Pipeline Authority. It was signed into law on April 11, 2007. The statutory mission of the Pipeline Authority is “to diversify and expand the North Dakota economy by facilitating development of pipeline facilities to support the production, transportation, and utilization of North Dakota energy-related commodities, thereby increasing employment, stimulating economic activity, augmenting sources of tax revenue, fostering economic stability and improving the State’s economy”. As established by the Legislature, the Pipeline Authority is a builder of last resort, meaning private business would have the first opportunity to invest in and/or build additional needed pipeline infrastructure. By law, the Pipeline Authority membership is comprised of the members of the North Dakota Industrial Commission. Upon the recommendation of the Oil and Gas Research Council, the Industrial Commission authorized the expenditure of up to $325,000 during the 2017-2019 biennium for the Pipeline Authority with funding being made available from the Oil and Gas Research Fund. On August 1, 2008 the Industrial Commission named Justin J. Kringstad, an engineering consultant, to serve as Director of the North Dakota Pipeline Authority. The North Dakota Pipeline Authority Director works closely with Lynn Helms, Department of Mineral Resources Director, Ron Ness, North Dakota Petroleum Council President and Karlene Fine, Industrial Commission Executive Director. -

ABOUT PIPELINES OUR ENERGY CONNECTIONS the Facts About Pipelines

ABOUT PIPELINES OUR ENERGY CONNECTIONS THE facts ABOUT PIPELINES This fact book is designed to provide easy access to information about the transmission pipeline industry in Canada. The facts are developed using CEPA member data or sourced from third parties. For more information about pipelines visit aboutpipelines.com. An electronic version of this fact book is available at aboutpipelines.com, and printed copies can be obtained by contacting [email protected]. The Canadian Energy Pipeline Association (CEPA) CEPA’s members represents Canada’s transmission pipeline companies transport around who operate more than 115,000 kilometres of 97 per cent of pipeline in Canada. CEPA’s mission is to enhance Canada’s daily the operating excellence, business environment and natural gas and recognized responsibility of the Canadian energy transmission pipeline industry through leadership and onshore crude credible engagement between member companies, oil production. governments, the public and stakeholders. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Canada’s Pipeline Network .................................1 2. Pipeline Design and Standards .........................6 3. Safety and the Environment ..............................7 4. The Regulatory Landscape ...............................11 5. Fuelling Strong Economic ................................13 and Community Growth 6. The Future of Canada’s Pipelines ................13 Unless otherwise indicated, all photos used in this fact book are courtesy of CEPA member companies. CANADA’S PIPELINE % of the energy used for NETWORK transportation in Canada comes 94 from petroleum products. The Importance of • More than half the homes in Canada are Canada’s Pipelines heated by furnaces that burn natural gas. • Many pharmaceuticals, chemicals, oils, Oil and gas products are an important part lubricants and plastics incorporate of our daily lives. -

Canadian Pipeline Transportation System Energy Market Assessment

National Energy Office national Board de l’énergie CANADIAN PIPELINE TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM ENERGY MARKET ASSESSMENT National Energy Office national Board de l’énergie National Energy Office national Board de l’énergieAPRIL 2014 National Energy Office national Board de l’énergie National Energy Office national Board de l’énergie CANADIAN PIPELINE TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM ENERGY MARKET ASSESSMENT National Energy Office national Board de l’énergie National Energy Office national Board de l’énergieAPRIL 2014 National Energy Office national Board de l’énergie Permission to Reproduce Materials may be reproduced for personal, educational and/or non-profit activities, in part or in whole and by any means, without charge or further permission from the National Energy Board, provided that due diligence is exercised in ensuring the accuracy of the information reproduced; that the National Energy Board is identified as the source institution; and that the reproduction is not represented as an official version of the information reproduced, nor as having been made in affiliation with, or with the endorsement of the National Energy Board. For permission to reproduce the information in this publication for commercial redistribution, please e-mail: [email protected] Autorisation de reproduction Le contenu de cette publication peut être reproduit à des fins personnelles, éducatives et/ou sans but lucratif, en tout ou en partie et par quelque moyen que ce soit, sans frais et sans autre permission de l’Office national de l’énergie, pourvu qu’une diligence raisonnable soit exercée afin d’assurer l’exactitude de l’information reproduite, que l’Office national de l’énergie soit mentionné comme organisme source et que la reproduction ne soit présentée ni comme une version officielle ni comme une copie ayant été faite en collaboration avec l’Office national de l’énergie ou avec son consentement. -

About Pipelines Our Energy Connections the Facts About Pipelines

OUR ENERGY CONNECTIONS ENERGY OUR ABOUT PIPELINES ABOUT Contact Us Canadian Energy Pipeline Association Tel: 403.221.8777 [email protected] aboutpipelines.com @aboutpipelines http://facebook.com/aboutpipelines Statistics Pipeline inside pocket inside IMPORTANT THE FACTS ABOUT PIPELINES This fact book is designed to provide easy access to information about the transmission pipeline industry in Canada. The facts are developed using CEPA member data or sourced from third parties. For more information about pipelines visit aboutpipelines.com. An electronic version of this fact book is available at aboutpipelines.com, and printed copies can be obtained by contacting [email protected]. The Canadian Energy Pipeline Association (CEPA) CEPA’s members represents Canada’s transmission pipeline companies transport around who operate 115,000 kilometres of pipeline in 97 per cent of Canada. CEPA’s mission is to enhance the operating Canada’s daily excellence, business environment and recognized natural gas and responsibility of the Canadian energy transmission pipeline industry through leadership and credible onshore crude engagement between member companies, oil production. governments, the public and stakeholders. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Canada’s Pipeline Network .................................1 2. Types of Pipelines ......................................................3 3. The Regulatory Landscape ..................................5 4. Building and Operating Pipelines....................6 5. CEPA Integrity First® Program ......................12 6. The History of Our Pipelines ..........................13 Unless otherwise indicated, all photos used in this fact book are courtesy of CEPA member companies. CANADA’S PIPELINE % of the energy used for NETWORK transportation in Canada comes 94 from refined petroleum products. The Importance of • More than half the homes in Canada are Canada’s Pipelines heated by furnaces that burn natural gas. -

Canadian Energy Research Institute

Canadian Energy Research Institute Capacity of the Western Canada Natural Gas Pipeline System SUMMARY REPORT – VOLUME 2 Peter H. Howard P.Eng David McColl Dinara Millington Paul R. Kralovic Study No. 113 – Summary Report Volume 2 ISBN No. 1-896091-81-4 Purchased by the State of Alaska January 2008 Relevant • Independent • Objective CAPACITY OF THE WESTERN CANADA NATURAL GAS PIPELINE SYSTEM SUMMARY REPORT VOLUME 2 ii Capacity of the Western Canada Natural Gas Pipeline System Copyright © Canadian Energy Research Institute, 2008 Sections of this study may be reproduced in magazine and newspapers with acknowledgement to the Canadian Energy Research Institute ISBN 1-896091-81-4 Authors: Peter Howard David McColl Dinara Millington Paul R. Kralovic CANADIAN ENERGY RESEARCH INSTITUTE #150, 3512 – 33 STREET NW CALGARY, ALBERTA CANADA T2L A6 TELEPHONE: (403) 282-1231 January 2008 Printed in Canada January 2008 Canadian Energy Research Institute iii The Canadian Energy Research Institute (CERI) is a cooperative research organization established by government and industry parties in 1975. Our mission is to produce relevant, independent, objective economic research and education in energy and environmental issues to benefit business, government, and the public. The sponsors of the Institute are Natural Resources Canada; the Alberta Department of Energy; the Private Sector Sponsors of the Canadian Energy Research Institute (composed of more than one hundred corporate members from the energy production, transportation, marketing, distribution, and consuming sectors in Canada and abroad and the financial community); the University of Calgary; the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board; the British Columbia Ministry of Energy and Mines; the Northwest Territories Department of Resources, Wildlife and Economic Development; Indian and Northern Affairs Canada; Alberta Research Council; and the Alberta Utilities Consumer Advocate. -

Pipeline Integrity Backgrounder

PipeIntegBGrnd08US.qxd:Backgrounder 4/21/09 8:47 AM Page 1 Alliance Pipeline Pipeline Integrity April 2009 Integrity Starts Here The Alliance Pipeline was built using the most advanced pipeline design and technology available, and we are committed to maintaining the system to provide a safe, efficient and environmentally responsible way to transport natural gas to our customers. We are regulated by federal agencies in both the U.S. and Canada that require us to demonstrate and document that the integrity of our pipeline facilities is maintained at all times. We’ve designed an Integrity Management Program that serves as the cornerstone of our pipeline design, operating and maintenance plans. This program helps us manage the pipeline, ensuring that the pipeline and related facilities consistently operate safely and reliably. We regularly meet or exceed all pipeline requirements and regulations. The integrity of our system also extends to our employees, who work in a culture that encourages Our company-wide inspection program helps us high standards in excellence, leadership and monitor the condition of the pipeline on an ongoing accountability. From design and construction, to basis, allowing us to take the appropriate and necessary operations and maintenance, keeping our steps to keep our system in top working order. communities and our employees safe is top of mind for everyone who works on the Alliance team. Working Together to Keep Our Communities Safe Safety By Design Ongoing education and public awareness about the The Alliance mainline system is made of high-strength existence of pipelines and how to safely live and work steel and a heavy-wall pipe that is generally thicker near them is essential to effective damage prevention. -

NAESB Members

North American Energy Standards Board Membership List As of July 31, 2021 NAESB membership extends to all employees of the member company, but does not extend to other companies with which the member company may have an organizational relationship – such as partnerships, liaisons, affiliates, subsidiaries, holding companies or parent companies. Should those companies be interested in joining they would hold separate memberships. Membership is specific to the quadrant(s) and segment(s) in which the company holds membership. Should an individual wish to represent a quadrant or segment in which the company member does not hold a membership, that individual will be considered a non-member. To obtain information on membership or verify membership status, please contact the NAESB Office ([email protected]). NAESB Membership Report - Quadrant/Segment Membership Analysis Number of Members WGQ Segments TOTAL 114 End Users 15 Distributors 22 Pipelines 35 Producers 9 Services 33 RMQ Segments TOTAL 36 Retail Electric End Users/Public Agencies 17 Retail Gas Market Interests Segment 8 Retail Electric Utilities 6 Retail Electric Service Providers/Suppliers 5 WEQ Segments TOTAL 131 End Users 15 Distributors 17 Transmission 41 Generation 20 Marketers 20 None Specified 1 Independent Grid Operators/Planners 7 Technology /Services 10 Total Membership 281 Page 1 North American Energy Standards Board Membership List As of July 31, 2021 Organization Seg1 Contact Retail Markets Quadrant (RMQ) Members: 1 Agility CIS s Mary Do 2 American Public Gas Association (APGA) g Donnie Sharp 3 Big Data Energy Services s J. Cade Burks, Jennifer Teel 4 California Energy Commission e Melissa Jones 5 California Public Utilities Commission e Katherine Stockton 6 CenterPoint Energy Houston Electric, LLC u John Hudson 7 City of Houston e Ray Cruz 8 Dominion Energy u Brandon Stites 9 Duke Energy Corporation u Stuart Laval, David Lawrence 10 Electric Reliability Council of Texas, Inc. -

Enbridge Profile

Out on the Tar Sands Mainline Mapping Enbridge’s Web of Pipelines A Corporate Profile of Pipeline Company Enbridge By Richard Girard, Polaris Institute Research Coordinator with Contributions from Tanya Roberts Davis Out on the Tar Sands Mainline: Mapping Enbridge’s Dirty Web of Pipelines May 2010 (partially updated, March 2012). The Polaris Institute The Polaris Institute is a public interest research and advocacy organization based in Canada. Since 1999 Polaris has been dedicated to developing tools and strategies for civic action on major public policy issues, including energy security, water rights and free trade. Polaris Institute 180 Metcalf Street, Suite 500 Ottawa, ON K2P 1P5 Phone : 613-237-1717 Fax: 613-237-3359 Email: [email protected] www.polarisinstitute.org For more information on the Polaris Institute’s energy campaign please visit www.tarsandswatch.org Table of Contents Foreword ......................................................................................................................... iv Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................3 1. Organizational Profile ...................................................................................................5 1.1 Enbridge’s Business Structure ....................................................................................5 1.1.1 Liquids -

Enbridge's Energy Infrastructure Assets

Enbridge’s Energy Infrastructure Assets Last Updated: Aug. 4, 2021 Energy Infrastructure Assets Table of Contents Crude Oil and Liquids Pipelines .................................................................................................... 3 Natural Gas Transmission Pipelines ........................................................................................... 64 Natural Gas Gathering Pipelines ................................................................................................ 86 Gas Processing Plants ................................................................................................................ 91 Natural Gas Distribution .............................................................................................................. 93 Crude Oil Tank Terminals ........................................................................................................... 96 Natural Gas Liquids Pipelines ................................................................................................... 110 NGL Fractionation ..................................................................................................................... 111 Natural Gas Storage ................................................................................................................. 112 NGL Storage ............................................................................................................................. 119 LNG Storage ............................................................................................................................ -

Alliance Pipeline Limited Partnership Annual

ALLIANCE PIPELINE LIMITED PARTNERSHIP ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM For the Year Ended December 31, 2019 April 29, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS.........................................................................................................................3 ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................9 FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION ................................................................................................ 10 CORPORATE STRUCTURE.................................................................................................................. 12 GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS...................................................................................... 12 General .................................................................................................................................................12 Recent Developments ..........................................................................................................................14 DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS ....................................................................................................... 15 The Alliance Pipeline System................................................................................................................15 RISK FACTORS.................................................................................................................................. 27 DESCRIPTION OF CAPITAL STRUCTURE -

2018 Management's Discussion and Analysis Alliance Pipeline Limited Partnership 2018 Management’S Discussion and Analysis

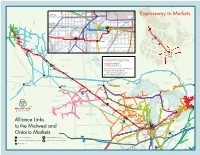

Alliance Pipeline Limited Partnership 2018 Management's Discussion and Analysis Alliance Pipeline Limited Partnership 2018 Management’s Discussion and Analysis The Alliance System The Alliance System (“System”) consists of a 3,849 kilometre (“km”) (2,392 mile) integrated Canadian and United States (“U.S.”) natural gas transmission pipeline, delivering rich natural gas from the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (“WCSB”) and the Williston Basin in North Dakota to the natural gas market in Chicago. The System has been in commercial service since December 2000 and currently delivers an average of 1.7 billion cubic feet per day (“bcf/d”) of rich gas to the Aux Sable natural gas liquids (“NGLs”) extraction facility, owned by Aux Sable Liquid Products L.P. (“Aux Sable”), an affiliate of Alliance Pipeline Limited Partnership (“Alliance Canada”). Rich gas is natural gas with relatively high NGLs content; mainly ethane, propane, butane and condensates. The System connects with the Aux Sable NGLs extraction facility in Channahon, Illinois, which extracts NGLs from the natural gas transported before delivery to downstream pipelines. The pipeline connects in the Chicago area, through its downstream header, with five interstate natural gas pipelines and two local natural gas distribution systems, which provide shippers with access to natural gas markets in the Midwest, the Northeast, and the Gulf Coast of the U.S., and Eastern Canada. All shippers have signed extraction agreements that give Aux Sable the right to extract the NGLs from the rich gas transported. The System also has three connections, two in North Dakota and one in Iowa, to provide for deliveries of small amounts of natural gas to ethanol production plants. -

Expressway to Markets Alliance Links to the Midwest

Joliet ACE Hub WILL COUNTY Expressway to Markets Delivery Segment NGPL ANR NICOR NGPL HORIZON PEOPLES NICOR NORTHERN BORDER ANR NORTHERN BORDER SPECTRA KENDALL COUNTY VECTOR NGPL GRUNDY COUNTY GUARDIAN PEOPLES GUARDIAN NORTHERN BORDER ALLIANCE PIPELINE VECTOR ANR PEOPLES TRANSCANADA Alliance Pipeline AUX HORIZON SPECTRA ALLIANCE PIPELINE SABLE Blueberry NGPL Ft. St. NICOR John ATP NICOR ALLIANCE PIPELINE MIDWESTERN SPECTRA Grande ALBERTA PEOPLES Prairie MIDWESTERN NICOR NGPL NICOR Windfall ALLIANCE PIPELINE Morinville ACE Edmonton Hub TRANSCANADA Contact us to learn how we can move SASKATCHEWAN MANITOBA Irma your liquids rich natural gas to market. 1-800-717-9017 ATP COCHIN Saskatoon www.alliancepipeline.com Customer Service: 403-517-6277 Option 1 Kerrobert Informational Postings Website: TCPL CANADIAN MAINLINE Calgary Loreburn http://ips.alliance-pipeline.com TRANSCANADA ALLIANCE PIPELINE Email: [email protected] BRITISH COLUMBIA AECO/NIT Regina TCPL CANADIAN MAINLINE QUEBEC Estlin Winnipeg UNION GAS ONTARIO UNION GAS EMERSON Thunder Bay KINGSGATE PORT OF UNION GAS MORGAN Alameda Sudbury TRANSCANADA NORTHERN BORDER Sault TIOGA VIKING Ste. Marie WBI UNION GAS Williston PRAIRIE ROSE Towner TRANSCANADAMINNESOTA EOG WBI NNG GREAT NNG Wimbledon LAKES TRANSMISSION Fargo TRANSCANADA GREAT UNION GAS NORTHERN NATURAL GAS NNG COCHIN WILLISTON BASIN INTERSTATE ENBRIDGE MONTANA Bismarck NNG ANR ANR Toronto Fairmount ROSHOLT NORTH DAKOTA HANKINSON WISCONSIN MICHIGAN VIKING WBI ALLIANCE PIPELINE Green Bay Minneapolis LAKES NIAGARA NORTHERN BORDER