The Breakdown of Nations Leopold Kohr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

5830 the LONDON GAZETTE, 4 SEPTEMBER, 1925. Amounts of the Accepted Tenders Must Be Made Mr

5830 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 4 SEPTEMBER, 1925. amounts of the accepted Tenders must be made Mr. Colin Stratton Stratton-Hallett as Consul to the Bank of England by means of Cash or a of Austria at Plymouth; Banker's Draft on the Bank of England not Sir Eric Hutchison as Consul of Belgium at later than 2 o'clock (Saturday 12 o'clock) on Leith; the day on which the relative Bills or Bonds Mr. J. 0. Duncan as Consul of Austria at are to be dated. Dublin; 10. In virtue of the provisions of Section 1 Mr. J. 0. Duncan as Consul of Bolivia at (4) of the War Loan Act, 1919, Members of the Dublin; House of Commons are not precluded from Mr. Cornelius Ferris as Consul of the United tendering for these Bills and Bonds. States of America at Cobh, Queenstown; Signor Edoardo Pervan as Consul of Italy afa 11. Tenders must be made on the printed Calcutta; forms, which may be obtained from the Chief Monsieur E. Antoine as Consul of Belgium at Cashier's Office, Bank of England. Perth, for Western Australia; 12. The Lords Commissioners of His Senor Don Alfonso P. Cainisuli as Consul of Majesty's Treasury reserve the right of reject- the Dominican Republic at Georgetown; ing any Tenders. Senor Don Armando de Leon y Valdes as Treasury Chambers, Consul of Cuba at Kingstown, Jamaica; Mr. John Seymour Bonito as Consul of 4th September, 1925. Denmark at Accra, for the Gold Coast; Mr. Harry J. Anslinger as Consul of the United States of America at Nassau; Senor Don Alfredo Waldeman Kraft as Consul Foreign Office, of Bolivia at Port of Spain; 19th December, 1924. -

Old Norvicensian

ON Old Norvicensian Features 018/2019 ONs are getting serious 2 about business (page 20-43) 1 Old Norvicensian Welcome Welcome Welcome to this year’s edition of the or even reach out to acquaintances with Old Norvicensian magazine. As ever, it whom you have lost contact. seeks to provide a link with your school Contents by updating you on news from Cathedral Attending an ON event is always a good Close, both in terms of activities of the way to reconnect; please be in touch with current school and alumni events. the Development Team if you would like further details of what is coming up. You However, it also seeks to offer stimulation are guaranteed a warm welcome in School 02 94 114 and reflection from the ongoing lives of House, where my colleagues and I will Norvicensians in the wider world. After all, always be pleased to update you on the News & Announcements Obituaries our direct contact ends relatively early in latest news and plans. Updates Weddings, babies Remembering those ONs who your lives and the most we can do is set Development and and celebrations have sadly passed away you up for your ongoing experiences; most I should like to finish by offering my thanks School news of your life is lived as an Old Norvicensian to those who have worked hard to produce and, if we get it right, the best bits happen such a quality document – happy reading! then, too! Steffan Griffiths I therefore hope that the pages which Head Master follow will be of interest in their own right but will also encourage reflection on your own experiences from school and since 44 that time. -

The Schumacher Enigma

The Schumacher Enigma by Peter Etherden first published in February 1999 in Fourth World Review Number 93 To those who grew up in the alternative movement in the sixties and seventies, E.F. Schumacher is a giant. The institutions he worked to create in his lifetime...he died in 1977...such as the Soil Association and Intermediate Technology, have gone from strength to strength. Small is Beautiful has become one of the few canons of our generation. If not everybody has read it, everybody has accepted its ideas...and this is very unusual in these days of fragmentation and relativity. We are all Schumacherians now. We have Schumacher Societies, Schumacher Lectures... and even grand prix racing drivers named after him. Yet there is an enigma at the centre of The Schumacher Legend. Why did Schumacher show so little interest in money? Small is Beautiful is in four parts: I: The Modern World; II: Resources; III: The Third World and IV: Organisation and Ownership. Size has its own chapter: A Question of Size...the Leopold Kohr's influence; Land is there with its own chapter: The Proper Use of Land; Technology is there with its own chapter: Social and Economic Problems Calling for the Development of Intermediate Technology; Work is there; Education, Labour, Employment. Everything is there except money, income, wages and capital. Why? The two principal sources for Small is Beautiful were articles commissioned by the editor of Resurgence, John Papworth and speeches Schumacher gave in his capacity as chief economist for the National Coal Board...modified to some degree (in Part IV) by his involvement with Ernest Bader's small business and by Bader's rather idiosyncratic decision to put his company in a trust for the workers rather than allowing his son to inherit the firm. -

Keynes and the Making of EF Schumacher

Keynes and the Making of E. F. Schumacher, 1929 - 1977 Robert Leonard* “I consider Keynes to be easily the greatest living economist”. Schumacher to Lord Astor, March 15, 19411 “The story goes that a famous German conductor was once asked: ‘Whom do you consider the greatest of all composers? ‘Unquestionably Beethoven’, he replied. ‘Would you not even consider Mozart?’. ‘Forgive me’, he said, ‘I though you were referring only to the others’. The same initial question may one day be put to an economist: ‘Who, in our lifetime, is the greatest? And the answer might come back: ‘Unquestionably Keynes’. ‘Would you not even consider Gandhi?’… ‘Forgive me, I thought you were referring only to all the others’”. Schumacher, in Hoda (1978), p.18 Introduction On Sunday, December 7, 1941, from a cottage deep in the Northamptonshire countryside, the 30- year old Fritz Schumacher wrote to fellow German alien, Kurt Naumann. He was reporting a recent encounter in London. “A man of great kindness, of downright charm; but, much more than I expected, the Cambridge don type. I had expected to find a mixture beween a man of action and a thinker; but the first impression is predominant, only that of a thinker. I do not know how far his practical influence goes today. Some tell me that it is extraordinarily great. The conversation was totally different from what I expected. I was ready to sit at his feet and listen to the Master’s words. Instead, there was an extremely lively discussion, a real battle of heavy artillery, and all this even though we were 99% in agreement from the outset. -

The Purpose of This Thesis Is to Trace Lady Katherine Grey's Family from Princess Mary Tudor to Algernon Seymour a Threefold A

ABSTRACT THE FAMILY OF LADY KATHERINE GREY 1509-1750 by Nancy Louise Ferrand The purpose of this thesis is to trace Lady Katherine Grey‘s family from Princess Mary Tudor to Algernon Seymour and to discuss aspects of their relationship toward the hereditary descent of the English crown. A threefold approach was employed: an examination of their personalities and careers, an investigation of their relationship to the succession problem. and an attempt to draw those elements together and to evaluate their importance in regard to the succession of the crown. The State Papers. chronicles. diaries, and the foreign correspondence of ambassadors constituted the most important sources drawn upon in this study. The study revealed that. according to English tradition, no woman from the royal family could marry a foreign prince and expect her descendants to claim the crown. Henry VIII realized this point when he excluded his sister Margaret from his will, as she had married James IV of Scotland and the Earl of Angus. At the same time he designated that the children of his younger sister Mary Nancy Louise Ferrand should inherit the crown if he left no heirs. Thus, legally had there been strong sentiment expressed for any of Katherine Grey's sons or descendants, they, instead of the Stuarts. could possibly have become Kings of England upon the basis of Henry VIII's and Edward VI's wills. That they were English rather than Scotch also enhanced their claims. THE FAMILY OF LADY KATHERINE GREY 1509-1750 BY Nancy Louise Ferrand A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of History 1964 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to Dr. -

Design Ecologies, Creative Labor and Hybrid Ecological Democracy Re-Enchanting Humanity to Prepare for the Just Transition Beyond Trump and End Times Ecology

Design Ecologies, Creative Labor and Hybrid Ecological Democracy Re-enchanting humanity to prepare for the Just Transition beyond Trump and End Times Ecology DRAFT, DRAFT, DRAFT, ROUGH, ROUGH, ROUGH Comments and critiques most welcome. Damian White The Rhode Island School of Design. [email protected] Design Ecologies, Creative Labor and Ecological Democracy Thinking the Just Transition beyond Trump and End Times Ecology Damian White, Professor of Social Theory and Environmental Studies, The Rhode Island School of Design [email protected] It could be argued that the project of ecological democracy that emerged from green political theory has been essentially concerned with finding ways to democratically regulate environmental limits. Conversely, theorizations of ecological democracy emerging out of political ecology, critical geography and STS have been rather more interested in finding ways to democratize the making of our hybrid social- natures. Each tradition of ecodemocratic thinking shares a desire to push back against eco-authoritarian ecologies that once had wide purchase on certain survivalist and apocalyptic ecologies of times past. But each tradition has had different foci of concerns generating a certain degree of disengagement and detachment. We find ourselves now in a context where the climate crisis continues, authoritarian populists are on the march and the project of ecological democracy seems ever more distant. The need for a just transition beyond fossil fuels becomes urgent, however an ecology of panic and hopelessness increasingly seems to pervade all manner of environmental discourse. In this paper I want to explore the role that emerging work in critical design studies might offer, in conjunction with emerging currents of labor focused political ecologies, to recharge the project of ecological democracy thus moving us beyond both end times ecology and Trump-ism. -

Ernst Friedrich Schumacher

Ernst Friedrich Schumacher Ernst Friedrich Schumacher "Fritz" (16 August 1911 – 4 September 1977) was an internationally influential economic thinker, statistician and economist in Britain, serving as Chief Economic Advisor to the UK National Coal Board for two decades. [ 1 ] His ideas became popularized in much of the English-speaking world during the 1970s. He is best known for his critique of Western economies and his proposals for human-scale, decentralized and appropriate technologies . According to The Times Literary Supplement , his 1973 book Small Is Beautiful : a study of economics as if people mattered is among the 100 most influential books published since World War II . [ 2 ] and was soon translated into many languages, bringing him international fame. Schumacher's basic development theories have been summed up in the catch-phrases Intermediate Size and Intermediate Technology . In 1977 he published A Guide For The Perplexed 1 / 8 Ernst Friedrich Schumacher as a critique of materialist scientism and as an exploration of the nature and organization of knowledge . Together with long-time friends and associates like Professor Mansur Hoda , Schumacher founded the Intermediate Technology Development Group (now Practical Action ) in 1966. Early life Schumacher was born in Bonn, Germany in 1911. His father was a professor of political economy. The younger Schumacher studied in Bonn and Berlin, then from 1930 in England as a Rhodes Scholar at New College, Oxford, [ 1 ] and later at Columbia University in New York City, earning a diploma in economics. He then worked in business, farming and journalism. [ 1 ] Economist Protégé of Keynes Schumacher moved back to England before World War II, as he had no intention of living under Nazism. -

Democracy and Liberalism – Harmony at Human Measure

1/11 Democracy and Liberalism – Harmony at human measure Christoph Heuermann University of Konstanz „Dosis facit venenum“ - the dose makes the venom – already was reported by the famous physician Paracelsus. This wisdom is not only applicable on the human organism, but also on society. Symptomatic for our time is the cult of the whopping, which not only extends to prestige-projects like the Elbphilharmony of Hamburg. Wilhelm Röpke, about whom we speak later in more detail, concludes this cult in wise buzzwords: Hybris, Rationalism, Szienticism, Technocracy, Socialism, Mass Democracy of Jacobine character (Röpke 1958). These buzzwords of the Big do not seem to correspond with the ideals of liberalism, but to harmonize with the reality of democracy. However, the more it looks like a stress ratio, the less it is one. Democracy harmonizes with Liberalism – but only at human measure. For what in today's political science is called „liberal democracies“ has to do little with both Democracy and Liberalism. What now is the human measure will be clarified after an introduction in the here used comprehension of both Democracy and Liberalism, adding further implications afterwards. Democracy and Liberalism are both concepts falling prey to a Babylonian confusion. This is nothing to wonder about since most old as new „Isms“ can be compared to a megalomania like the building of the tower of Babel, because they overstretch comprehensible ideas to dangerous extremes. The idea historian Eric Voegelin saw this as the consequence of a political gnosticism, which leads to the three central types of progressivism, utopism and revolutionary activism (Voegelin 1999: 107f). -

Grassroots Post-Modernism Is Daring in Its Thesis That the Real Postmodernists Are to Be Found Among the Zapotecos and Rajasthanis of the Majority World

Grassroots Post-Modernism Remaking the soil of cultures Gustavo Esteva & Madhu Suri Prakash i 'Beyond its definite "No" to the Global Project, this book takes a stimulating glance at the renewed life of social majorities and offers good reasons for a common hope! GILBERT RIST 'Grassroots Post-modernism is daring in its thesis that the real postmodernists are to be found among the Zapotecos and Rajasthanis of the majority world. It is hard-hitting in its attacks against progressive commonplaces, like global responsibility, human rights, the autonomy of the individual, and democracy. And it is eye-opening in its illustrations of how ordinary people, amidst the rubble of the development epoch, stitch their cultural fabric together and unwittingly move beyond the impasse of modernity.' WOLFGANG SACHS 'Esteva and Prakash courageously and clear-sightedly take on some of the most entrenched of modern certainties such as the universality of human rights, the individual self, and global thinking. In their efforts to remove the lenses of modernity that education has bequeathed them, they dig deep into their own encounters with what they call the "social majorities" in their native Mexico and India. There they see not an enthralment with the seductions of modernity but evidence of a will to live in their own worlds according to their own lights. Esteva's and Prakash's reflections on the imperialism of the universality of human rights avoids the twin pitfalls of relativism and romanticism. Their alternative is demanding and novel, and deserves our most serious consideration. Grassroots Post-modernism is a much needed and most welcome counterpoint both to the nihilism of much post-modern thinking as well as to those who view the spread of the global market and of global thinking too triumphantly.' FREDERIQUE APFFEL-MARGLIN 'Quite simply, a book which will transform how one sees the world.’ NORTH AND SOUTH ii iii ABOUT THE AUTHORS GUSTAVO ESTEVA is one of Latin America's most brilliant intellectuals and a leading critic of the development paradigm. -

RES U R GEN CE Journal of the Fourth World Contents Contributors

RES U RGEN CE Journal of the Fourth World 24 Abercom Place, St. John's Wood, London, N.W.8 Vol. 3, No. 6 March/April 1971 Contents Editorial Group Roger Franklin Managing Editor 3 The Europe of a Thousand Flags Editorial Miles Gibson Layout and Art 7 Poems: 'Advent' John Haag Stephen Horne Newsletter 'Error' David Morris Michael and Frances Horovitz Poetry 8 Modern Industry in the E. F. Schumacher David Kuhrt Light of the Gospel Graham Keen Layout and Art 12 Quotes John Lloyd Publicity Business and 14 The Common Market Leopold Kohr Michael North subscriptions 17 Review, 'The Guilty Bystander' Dave Cunliffe John Papworth Editor 18 Letters Mrs. M. Rohde French Monitor 20 Cars, Profits and Pollution from WIN Andrew Singer German Monitor Martin Thom Spanish Monitor 22 Review, 'Love Poems' Miles Gibson Associate Editors: Ernest Bader, Danilo 23 Urban Notebook John Papworth Dolci, Paul Goodman, Ray Gosling, Prof. Leopold Kohr, jayaprakash 27 Poem, 'Links' David Cha/caner Narayan, Dr. E. F. Schumacher. MILES GIBSON-Born: New Forest, LEOPOLD KOHR, a native of Contributors: 1947. Educated: Yes. Published: Yes, Oberndorf, near Salzburg, graduated see Review; also articles for Daily from the Universities of Vienna and Telegraph Magazine. Works: Yes. Innsbruck; he left Austria during Married; lives in London. the dictatorship of Dolfuss and pur The C 0 VE R, drawn by MILES sued his studies further at the GIBSON, is based on a map from University of Paris and the London Leopold Kohr's book 'The Break School of Economics. He had a down of Nations' ( 1957 ). -

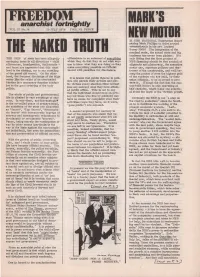

Scanned Image

anarchist fortnightly , l 7 No.1 TWE LVE PENCE _ lllllli IS, THE NATIONAL Enterprise Board paying Mark Phillips to drive around ostentatiously in his new Leyland A Rover 3500'? The integration of the nominal state, the actual state and big business has never been plainer. It's TI-IE SHIP of state has been allegedly officialdom is so ashamed of everfihing only fitting that the first product of springing leaks in all directions - child which they do that they do not wish any- NEB financing should be that symbol of allowances, immigration, thalidomide - one to 1(IlOW'..Wh8.ll they are doing so they oligarchy and plutocracy, the executive and fears are expressedithat this must make everything possible an Official motor car, supreme polluter and des- lead to the sinking, not to say scuttling Secret with penalties for disclosure. troyer of the countryside, and well be- of the grand old vessel. On the other yong the pocket of even the highest paid hand, the frequent discharge of the bilge 0 of the workers who are said, by their water like the relief of an overloaded It is ironic that public figures in poli- tics who parade their private and pub- union officials, to be so proud to pro- bladder is a necessary function conduc- lic virtues every election-time retreat duce it . (Though the fact that the cus- ive to the good ordering of the body into coy secrecy once they have attain- tom-built facory is only operating at politic. half capacity, might make one sceptic- ed public office.