Historical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

G E R a L D I N E C R A

GERALDINE CRAIG 111 Willard Hall Manhattan, KS 66506-3705 [email protected] E DUCATION 1987 - 1989 M.F.A. Fiber, Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, MI 1977 - 1982 B.F.A. Textile Design, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS B.F.A. History of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 1979 - 1980 University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, Scotland (Philosophy, Art History) P ROF E SSIONAL E X pe RI E NC E 2007 - Professor of Art Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS Associate Dean of the Graduate School (2014-2018) Department Head of Art (2007-2014) Associate Professor of Art (2007-2014) 2001 - 2007 Assistant Director for Academic Programs Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, MI Developed annual Critical Studies/Humanities program; academic administration 2005 - Regional Artist/Mentor, Vermont College M.F.A. Program Vermont College, Montpelier, VT 1995 - 2001 Curator of Education/Fine and Performing Arts Wildlife Interpretive Gallery, Detroit Zoological Institute, Royal Oak, MI Develop/manage permanent art collection, performing arts programs, temporary exhibits 1994 - 1995 James Renwick Senior Research Fellowship in American Crafts Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 1990 - 1995 Executive Director Detroit Artists Market, (non-profit art center, est. 1932), Detroit, MI 1990 - 1993 Instructor Fiber Department, College for Creative Studies, Detroit, MI 1990 Instructor Red Deer College, Alberta, Canada 1989 - 1990 Registrar I Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI 1987 Associate Producer Lyric Theater, Highline Community College, -

ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL

T HE CHILD’ S WORLD® ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL VOLUME 3: REGGIE JACKSON THROUGH OUTFIELDER T HE CHILD’ S WORLD® ENCYCLOPEDIA of BASEBALL VOLUME 3: REGGIE JACKSON THROUGH OUTFIELDER By James Buckley, Jr., David Fischer, Jim Gigliotti, and Ted Keith KEY TO SYMBOLS Throughout The Child’s World® Encyclopedia of Baseball, you’ll see these symbols. They’ll give you a quick clue pointing to each entry’s general subject area. Active Baseball Hall of Miscellaneous Ballpark Team player word or Fame phrase Published in the United States of America by The Child’s World® 1980 Lookout Drive, Mankato, MN 56003-1705 800-599-READ • www.childsworld.com www.childsworld.com ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Child’s World®: Mary Berendes, Publishing Director Produced by Shoreline Publishing Group LLC President / Editorial Director: James Buckley, Jr. Cover Design: Kathleen Petelinsek, The Design Lab Interior Design: Tom Carling, carlingdesign.com Assistant Editors: Jim Gigliotti, Zach Spear Cover Photo Credits: Getty Images (main); National Baseball Hall of Fame Library (inset) Interior Photo Credits: AP/Wide World: 5, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 52, 56, 57, 59, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 70, 72, 74, 75, 78, 79, 80, 83, 75; Corbis: 18, 22, 37, 39; Focus on Baseball: 7t, 10, 11, 29, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41, 49, 51, 55, 58, 67, 69, 71, 76, 81; Getty Images: 54; iStock: 31, 53; Al Messerschmidt: 12, 48; National Baseball Hall of Fame Library: 6, 7b, 28, 36, 68; Shoreline Publishing Group: 13, 19, 25, 60. -

Chief Bowlegs and the Banana Garden: a Reassessment of the Beginning of the Third Seminole War

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 Chief Bowlegs and the Banana Garden: A Reassessment of the Beginning of the Third Seminole War John Settle University of Central Florida Part of the Public History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Settle, John, "Chief Bowlegs and the Banana Garden: A Reassessment of the Beginning of the Third Seminole War" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1177. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1177 CHIEF BOWLEGS AND THE BANANA GARDEN: A REASSESSMENT OF THE BEGINNING OF THE THIRD SEMINOLE WAR by JOHN D. SETTLE B.A. University of Central Florida, 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2015 Major Professor: Daniel Murphree © 2015 John Settle ii ABSTRACT This study examines in depth the most common interpretation of the opening of the Third Seminole War (1855-1858). The interpretation in question was authored almost thirty years after the beginning of the war, and it alleges that the destruction of a Seminole banana plant garden by United States soldiers was the direct cause of the conflict. -

Raging Moderates: Second Party Politics and the Creation of a Whig Aristocracy in Williamson County, Tennessee, 1812-1846 Robert Holladay

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Raging Moderates: Second Party Politics and the Creation of a Whig Aristocracy in Williamson County, Tennessee, 1812-1846 Robert Holladay Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE RAGING MODERATES: SECOND PARTY POLITICS AND THE CREATION OF A WHIG ARISTOCRACY IN WILLIAMSON COUNTY, TENNESSEE, 1812-1846 By ROBERT HOLLADAY A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 Copyright 2007 Robert Holladay All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Robert Holladay defended on March 23, 2007. —————————————— Albrect Koschnik Professor Directing Thesis —————————————— James P. Jones Minor Professor —————————————— Matt Childs Outside Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A 48-year-old ex-journalist who decides to go to graduate school has a lot of people to thank. First and foremost is my wife, Marjorie, who has endured family crises and the responsibility of being the primary breadwinner in order to allow me to pursue a dream. She is my rock. Secondly, my late uncle, Wendell G. Holladay, former Provost at Vanderbilt University encouraged me to return to school and looked forward to reading this thesis when it was finished. My mother, who also died in the middle of this process, loved history and, along with my father, instilled that love in me. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

PIIIII-IIIIIPI Covers Less Area • Nelli

ALL-CITY Caddies to Be Scarce Again DITROIT SUNDAY TUNIS C April 15, 1945—1, Page 3 Sparing Firing Line' THE GREATER GAME By Edgar Hayes ¦p „ ? ????? y * ... riHtf-• PLEA: LIGHT BAGS FOR LIGHT BOYS Set for Shoot Times Sports Writer No Pins By M. F. DRUKENBROD 'Dotte Hi' Leads Caddie superintendents and golf Awarded Silver Star Three E&B Bowlers pros are agreed there'll be no relief in the caddie situation here Hearst Entries ) on All-City Team this season. Lt. Sheldon Moyer, who wrote Michigan State sports for time, there won’t Until vacation By GILLIES The Detroit Times for four years, has been awarded the Silver to DON be enough boys go around and Star for heroism in action, it was learned in a letter from Georgt By HAROLD KAHL even then, not enough for week- Bullets will whiz south instead x. wf ends and special occasions. of north when more than 3,000 Maskin, another Times sports writer w’ho is in London. League and tournament play JOE NORRIS This means doubling up, two shooters fire their matches in the Lt. Moyer was honored for his part in saving a lot of equip- were the prime requisites in the bags for one boy, a problem in (Stroh) fifth annual llearst-Times tourna- ment for an armored division the Germans had started to shell. itself, the caddies again Wg¥ \ \ selection of the top 25 bowlers in because .aHSU-'---¦¦¦ J V Moyer was wounded in the action but has completely recovered. be and younger than ment at Olympia, April 28 and 29. -

Lieutenant Governor of Missouri

CHAPTER 2 EXECUTIVE BRANCH “The passage of the 19th amendment was a critical moment in our nation’s history not only because it gave women the right to vote, but also because it served as acknowledgement of the many significant contributions women have made to our society, and will make in the future. As the voice of the people of my legislative district, I know I stand upon the shoulders of the efforts of great women such as Susan B. Anthony and the many others who worked so diligently to advance the suffrage movement.” Representative Sara Walsh (R-50) OFFICE OF GOVERNOR 35 Michael L. Parson Governor Appointed June 1, 2018 Term expires January 2021 MICHAEL L. PARSON (Republican) was sworn in The governor’s proposal to improve economic as Missouri’s 57th governor on June 1, 2018, by and workforce development through a reorgani- Missouri Supreme Court Judge Mary R. Russell. zation of state government was overwhelmingly He came into the role of governor with a long- supported by the General Assembly. Through time commitment to serving others with over 30 these reorganization efforts, government will be years of experience in public service. more efficient and accountable to the people. Governor Parson previously served as the The restructuring also included several measures 47th lieutenant governor of Missouri. He was to address the state’s growing workforce chal- elected lieutenant governor after claiming victory lenges. in 110 of Missouri’s 114 counties and receiving Governor Parson spearheaded a bold plan to the most votes of any lieutenant governor in Mis- address Missouri’s serious infrastructure needs, souri history. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

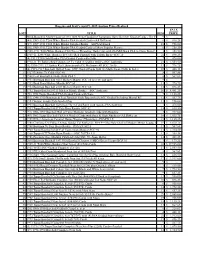

PDF of Apr 15 Results

Huggins and Scott's April 9, 2015 Auction Prices Realized SALE LOT# TITLE BIDS PRICE 1 Mind-Boggling Mother Lode of (16) 1888 N162 Goodwin Champions Harry Beecher Graded Cards - The First Football9 $ Card - in History! [reserve not met] 2 (45) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards—All Different 6 $ 896.25 3 (17) 1909-1911 T206 White Border Tougher Backs—All PSA Graded 16 $ 956.00 4 (10) 1909-1911 T206 White Border PSA Graded Cards of More Popular Players 6 $ 358.50 5 1909-1911 T206 White Borders Hal Chase (Throwing, Dark Cap) with Old Mill Back PSA 6--None Better! 3 $ 358.50 6 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Red Portrait) with Tolstoi Back--SGC 10 21 $ 896.25 7 (4) 1911 T205 Gold Border PSA Graded Cards with Cobb 7 $ 478.00 8 1910-11 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets #9 Ty Cobb (Checklist Offer)--SGC Authentic 21 $ 1,553.50 9 (4) 1910-1911 T3 Turkey Red Cabinets with #26 McGraw--All SGC 20-30 11 $ 776.75 10 (4) 1919-1927 Baseball Hall of Fame SGC Graded Cards with (2) Mathewson, Cobb & Sisler 10 $ 448.13 11 1927 Exhibits Ty Cobb SGC 40 8 $ 507.88 12 1948 Leaf Baseball #3 Babe Ruth PSA 2 8 $ 567.63 13 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle SGC 10 [reserve not met] 9 $ - 14 1952 Berk Ross Mickey Mantle SGC 60 11 $ 776.75 15 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle SGC 60 12 $ 896.25 16 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle Rookie—SGC Authentic 10 $ 4,481.25 17 (76) 1952 Topps Baseball PSA Graded Cards with Stars 7 $ 1,135.25 18 (95) 1948-1950 Bowman & Leaf Baseball Grab Bag with (8) SGC Graded Including Musial RC 12 $ 537.75 19 1954 Wilson Franks PSA-Graded Pair 11 $ 956.00 20 1955 Bowman Baseball Salesman Three-Card Panel with Aaron--PSA Authentic 7 $ 478.00 21 1963 Topps Baseball #537 Pete Rose Rookie SGC 82 15 $ 836.50 22 (23) 1906-1999 Baseball Hall of Fame Manager Graded Cards with Huggins 3 $ 717.00 23 (49) 1962 Topps Baseball PSA 6-8 Graded Cards with Stars & High Numbers--All Different 16 $ 1,015.75 24 1909 E90-1 American Caramel Honus Wagner (Throwing) - PSA FR 1.5 21 $ 1,135.25 25 1980 Charlotte O’s Police Orange Border Cal Ripken Jr. -

Houston Builders Association •

The Official Magazine of the Greater Houston Builders Association • www.ghba.org AUGUST 2018 HOUSTON Builder Custom Lighting & Hardware is now Ferguson Bath, Kitchen & Lighting Gallery – the premiere showroom for ALSO INSIDE: the Greater Houston area Harris County Bond Election pg 8, 12 page 21 Carpentry Education Program Launches in NW Houston pg 18 Project Playhouse Winner Revealed pg 24 CUSTOM BUILDERS’ FIRST CHOICE FOR HIGH QUALITY LUMBER... FAST! NEXT DAY DELIVERY ON FRAME PACKAGES, SAME DAY ON FILL-IN ORDERS FAMILY OWNED & OPERATED FOR SIX GENERATIONS WE CARRY: ...AND MORE! NOW AVAILABLE! Call (713) 329-5300 FRAMING LUMBER PLYWOOD & OSB TREATED LUMBER ANTHONY POWER BEAMS SIDING & TRIM CUSTOM FLOOR TRUSSES SCHOLL LUMBER | 6202 N HOUSTON ROSSLYN ROAD | HOUSTON, TX 77091 | SCHOLLLUMBER.COM NEW FiberCraft ® Composite and ThermaPlus® Steel! “Looks so good, you’ll think it’s wood.” TM See why these are The Better Doors. FiberCraft® Composite® ThermaPlus® ThermaPlus® • FiberCraft Composite Arch Lite Double Doors are premium in features, yet priced as standard orders, not custom. • Available with Impact Rated Options and with multiple glass textures for both impact and non-impact doors. • No unsightly plugs around the door frames. • ThermaPlus are thermally broken and field-trimmable steel doors priced 40% less than most premium steel entry doors. Wide range of design options. Built secure and strong. • Authentic raised moulding on 18 gauge thick steel doors. • Windstorm rated options available (80 DP Ratings). GlassCraft products are available at your leading millwork distributors and dealers nationwide. Contact us for details: Visit www.glasscraft.com 713-690-8282 | 2002 Brittmoore Rd., Houston TX 77043 www.glasscraft.com® CONTENTS ON THE COVER HOUSTON BuilderThe Official Magazine of the Greater Houston Builders Association August 2018|Volume 31|Number 08 FEATURES Action Alert: Vote for Proposition A New look. -

The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Michael Dudley, "Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 894. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/894 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FULCRUM OF THE UNION: THE BORDER SOUTH AND THE SECESSION CRISIS, 1859- 1861 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Michael Dudley Robinson B.S. North Carolina State University, 2001 M.A. University of North Carolina – Wilmington, 2007 May 2013 For Katherine ii Acknowledgements Throughout the long process of turning a few preliminary thoughts about the secession crisis and the Border South into a finished product, many people have provided assistance, encouragement, and inspiration. The staffs at several libraries and archives helped me to locate items and offered suggestions about collections that otherwise would have gone unnoticed. I would especially like to thank Lucas R. -

Test!Cooperationworking Together Toward a Common Goal

Atchison County Mail March 26, 2015 Page 7 Blue Jay Corner What did you do on State St. Patrick’s Day? Testing Senior 2015 Starts “We had treats and read madison a story. We got to do April 1. different activities.” Come to -Avery Meyerkorth, 2nd Middletaylor Name: Leigh Grader school Favorite Vacation Location: Outer Banks, NC rested, Favorite Store: Forever 21 “I was sick and didn’t get Favorite Celebrity: Audrey Hepburn fed, and Favorite Disney Character: Ariel to do much. I stayed home Favorite Television Show: Vampire and rested.” ready to Diaries -Joshua Lucas, Junior Role Model: Nana Smash the Pet Peeve: When people don’t have man- Test! ners COOPERATION Biggest Fear: Getting in a car accident Advice to Underclassmen: Don’t worry “I ate some corn beef and about drama veggies.” Working together Future Plans: Attend UNL and major in Shelby Bremer, Senior Biology common goal. By Amber Cook BLUE JAYS OF THE WEEK toward a MARCH 20, 2015 “I enjoyed a shamrock Mrs. Farley: Brock Sebek- shake from McDonald’s.” Holmes Mrs. Hughes: Westyn Amthor Chloe Sierks, Junior Mrs. Yocum: Jacoby Driskell Mrs. Bredensteiner: Ryder By Kaleigh Farmer Herron Mrs. Vette: James Herron top Mrs. Lawrence: Savannah What should your job be? Found out the top ten jobs for 2015! The student newspaper of Caldwell AY 10 www.msn.com By Dayle Davis Rock Port R-II Schools. Mrs. Amthor: Jaysa Welch 600 S. Nebraska Street Median Salary J Mrs. Geib: Abby Minino corner Rock Port, MO 64482 Mrs. Gilson: Teagan Green Dentist $146,340 Layout: Dayle Davis Adviser: Amy Skillen.