Development of Adelaide West Beach Airport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monana the OFFICIAL PUBLICATION of the AUSTRALIAN METEOROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION INC June 2017 “Forecasting the November 2015 Pinery Fires”

Monana THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE AUSTRALIAN METEOROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION INC June 2017 “Forecasting the November 2015 Pinery Fires”. Matt Collopy, Supervising Meteorologist, SA Forecasting Centre, BOM. At the AMETA April 2017 meeting, Supervising Meteorologist of the Bureau of Meteorology South Australian Forecasting Centre, gave a fascinating talk on forecasting the conditions of the November 2015 Pinery fires, which burnt 85,000ha 80 km north of Adelaide. The fire started during the morning of Wednesday 25th November 2015 ahead of a cold frontal system. Winds from the north reached 45-65km/h and temperatures reached the high 30’s, ahead of the change, with the west to southwest wind change reaching the area at around 2:30pm. Matt’s talk highlighted the power of radar imagery in improving the understanding of the behaviour of the fire. The 10 minute radar scans were able to show ash, and ember particles being lofted into the atmosphere, and help identify where the fire would be spreading. The radar also gave insight into the timing of the wind change- vital information as the wind change greatly extends the fire front. Buckland Park radar image from 2:30pm (0400 UTC) on 25/11/2015 showing fine scale features of the Pi- nery fire, and lofted ember particles. 1 Prediction of fire behaviour has vastly improved, with Matt showing real-time predictions of fire behaviour overlain with resulting fire behaviour on the day. This uses a model called Phoenix, into which weather model predicted conditions, and vegetation information are fed to provide a model of expected fire behaviour. -

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

AAA SA Meeting Minutes

MINUTES SOUTH AUSTRALIAN AAA DIVISION MEETING AND AGM Stamford Grand Adelaide, Moseley Square, Glenelg 25 & 26 August 2016 ATTENDEES PRESENT: Adam Branford (Mount Gambier Airport), Ian Fritsch (Mount Gambier Airport), George Gomez Moss (Jacobs), Alan Braggs (Jacobs), Cr Julie Low (Mayor, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula), Barrie Rogers (Airport Manager District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula), Ken Stratton (Port Pirie Regional Council), Peter Francis (Aerodrome Design), Bill Chapman (Mildura Airport), Laura McColl (ADB Safegate), Shane Saal (Port Augusta City Council), Heidi Yates (District Council of Ceduna), Howard Aspey (Whyalla City Council), Damon Barrett (OTS), James Michie (District of Coober Pedy), Phil Van Poorten (District of Coober Pedy), Cliff Anderson (Fulton Hogan), David Blackwell (Adelaide Airport), Gerard Killick (Fulton Hogan), Oliver Georgelin (Smiths Detection), Martin Chlupac (Airport Lighting Specialists), Bridget Conroy (Rehbein Consulting), Ben Hargreaves (Rehbein Consulting), David West (Kangaroo Island Council), Andrew Boardman (Kangaroo Island Council), Phil Baker (Philbak Pty Ltd), Cr Scott Dornan (Action line marking), Allan Briggs (Briggs Communications), David Boots (Boral Asphalt), Eric Rossi (Boral Asphalt), Jim Parsons (Fulton Hogan), Nick Lane (AAA National), Leigh Robinson (Airport Equipment), Terry Buss (City of West Torrens), David Bendo (Downer Infrastructure), Erica Pasfield (Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure), Chris Van Laarhoven (BHP Billiton), Glen Crowhurst (BHS Billiton). -

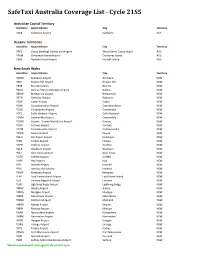

Safetaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi Australia Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Australian Capital Territory Identifier Airport Name City Territory YSCB Canberra Airport Canberra ACT Oceanic Territories Identifier Airport Name City Territory YPCC Cocos (Keeling) Islands Intl Airport West Island, Cocos Island AUS YPXM Christmas Island Airport Christmas Island AUS YSNF Norfolk Island Airport Norfolk Island AUS New South Wales Identifier Airport Name City Territory YARM Armidale Airport Armidale NSW YBHI Broken Hill Airport Broken Hill NSW YBKE Bourke Airport Bourke NSW YBNA Ballina / Byron Gateway Airport Ballina NSW YBRW Brewarrina Airport Brewarrina NSW YBTH Bathurst Airport Bathurst NSW YCBA Cobar Airport Cobar NSW YCBB Coonabarabran Airport Coonabarabran NSW YCDO Condobolin Airport Condobolin NSW YCFS Coffs Harbour Airport Coffs Harbour NSW YCNM Coonamble Airport Coonamble NSW YCOM Cooma - Snowy Mountains Airport Cooma NSW YCOR Corowa Airport Corowa NSW YCTM Cootamundra Airport Cootamundra NSW YCWR Cowra Airport Cowra NSW YDLQ Deniliquin Airport Deniliquin NSW YFBS Forbes Airport Forbes NSW YGFN Grafton Airport Grafton NSW YGLB Goulburn Airport Goulburn NSW YGLI Glen Innes Airport Glen Innes NSW YGTH Griffith Airport Griffith NSW YHAY Hay Airport Hay NSW YIVL Inverell Airport Inverell NSW YIVO Ivanhoe Aerodrome Ivanhoe NSW YKMP Kempsey Airport Kempsey NSW YLHI Lord Howe Island Airport Lord Howe Island NSW YLIS Lismore Regional Airport Lismore NSW YLRD Lightning Ridge Airport Lightning Ridge NSW YMAY Albury Airport Albury NSW YMDG Mudgee Airport Mudgee NSW YMER Merimbula -

Submission on Integrated Movement Systems Discussion Paper

5 November 2018 Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure Dear Sir / Madam City of Salisbury submission on Integrated Movement Systems Discussion Paper Thank you for the opportunity to make a submission on the Integrated Movement Systems Discussion Paper. Council has been in caretaker mode for the Local Government Elections, and will consider this matter at its December round of meetings. The submission does however reflect various positions of Council that have been endorsed, and is considered to be consistent in its comments. A number of detailed comments are provided in the table at the end of the letter, but the key submission points are as follows: Airport policy consideration The City of Salisbury has within it two significant airports. Parafield Airport is a general aviation airport that also provides for aviation training facilities which includes repeated landing and take-off flight circuit training, and the RAAF Base Edinburgh which is a significant military airport that is home to long range surveillance aircraft and is utilised by jet fighters and support planes. Council is acutely aware of the impacts of airport operations on the community and also by the implementation of the National Airports Safeguarding Framework federal guidelines which includes airplane noise levels, and a recent draft Guideline on Public Safety Areas. There are a number of Guidelines of varying impacts and controls on development around airports, but these two significantly affect a large number of properties, with differing levels of policy requirements depending upon the airport type. It is considered that the Discussion Paper is almost silent both on the impact of airports on the communities around them, and as economic drivers in their own right. -

Parafield - Adelaide/YPPF

Parafield - Adelaide/YPPF 26th of January 2021 V1.01 MSFS Manual Page | 1 Contents Product Versions 3 History 4 About the Airport 5 Installation 6 Airport Charts 7 Support 8 Credits 9 Page | 2 Product Versions 8th of January 2021 – V1.0 • Initial MSFS release 26th of January 2021 – V1.01 • Fixed the tower glass rendering transparency • Corrected circuit pattern direction Page | 3 History Parafield (YPPF) is located 18km north of Adelaide city centre, being established in 1927 parafield remained Adelaide’s only civil airport till 1955 when Adelaide Airport was opened. Situated at 57ft above sea level. Parafield has four runways ranging from 958m – 1350m. Only runway 21R/03L is lighted for night operations. Be sure to checkout the Parafield Air Traffic Control Tower which has been listed on the Australian Commonwealth Heritage List. Page | 4 About the Airport Welcome to Parafield (YPPF) V1.01 for Microsoft Flight Simulator 2020! Parafield is home to many flying schools where a large number of domestic and international students conduct their training and contribute to make this the third busiest airport by aircraft movements in Australia. Situated just north of the major airport Adelaide, Parafield offers a perfect base for you to explore South Australia or learning the in’s and out’s of this busy airfield. The airport has been hand crafted with a high level of precision using hundreds of on-site photos to include many bespoke details for you to discover. We truly hope you will enjoy this highly realistic version of Parafield airport. Features: • Hand Crafted Rendition of Parafield for MSFS • MSFS Native Product • High Resolution PBR textures • Detailed aprons • Dynamic rain on control tower glass • Bespoke details • Custom photoreal signs • Genuine night experience • Custom taxiway lines and markings • Detailed Static Aircraft and AI Traffic Ready • Dynamic lighting Page | 5 Installation To ensure our product installs correctly please ensure you direct the installation to your community folder in MSFS. -

Air Services Amendment Bill 2018 Submission 44

Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Please accept the following submission on behalf of the City of Salisbury on this matter. The City of Salisbury is a suburban Council in metropolitan Adelaide, South Australia and is home to both Parafield Airport and Edinburgh Defence Base. We only became aware of the Air Services Amendment Bill and the Inquiry on the 28th May 2018 and we are disappointed, as a significant stakeholder in airport operations, that we were not made aware of the Bill and Inquiry in any formal manner that would allow proper consideration of the proposed Bill and its implications for the Salisbury Community. The City of Salisbury has within it a significant general aviation and flight training airport, Parafield Airport, which is managed by the Adelaide Airport. Its approved 2017 Master Plan indicates that the runway capacity is 450,000, and has a current movement of 214,000, with the 2037 forecast being 340,000 movements. I have attached the submission Council made on the Master Plan for the Inquiry information and use. It should be noted that the submission makes comments on reviewing the voluntary curfew, flight training circuits, and provision of a noise attenuation program. The submission also comments on the community feedback on investigating and resolving noise complaints, and seeks a review of the consultation methodology of Master Plans, and improvements to the complaint system and the membership selection process of the Consultative Committee. Council receives frequent complaints from residents under or near the Parafield Airport flight paths about the impacts of aircraft movements upon their amenity. -

Adelaide and Regional Airsheds Report 1998-99

South Australian National Pollutant Inventory SUMMARY REPORT ADELAIDE AND REGIONAL AIRSHEDS AIR EMISSIONS STUDY 1998–99 Prepared by Dr Jolanta Ciuk Environment Protection Authority South Australia South Australian NPI Summary Report Adelaide and regional airsheds air emissions study 1998–99 This document is a summary of the NPI aggregated air emissions estimated in the South Australian airsheds for 1998–99. Aggregate and industry reported emissions data are accurate at the time of printing. Author: Dr Jolanta Ciuk For further information please contact: Information Officer Environment Protection Authority GPO Box 2607 Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone: (08) 8204 2004 Facsimile: (08) 8204 9393 Freecall (country): 1800 623 445 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.epa.sa.gov.au ISBN 1 876562 37 4 JUNE 2002 © Environment Protection Authority This document may be reproduced in whole or part for the purposes of study or training, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source and its not being used for commercial purposes or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires the prior written permission of the South Australian Environment Protection Authority. Printed on recycled paper Contents Executive summary ix Introduction ix Background ix Airsheds ix Air emission sources x Results x Key conclusions and recommendations xi Section 1: Introduction 1 1.1 Study areas—airsheds 2 1.2 Air emission sources 10 1.3 Domestic survey 11 Section 2: Mobile sources 12 2.1 Aeroplanes 12 2.2 Motor vehicles 18 2.3 Railways -

Monthly Weather Review South Australia August 2008 Monthly Weather Review South Australia August 2008

Monthly Weather Review South Australia August 2008 Monthly Weather Review South Australia August 2008 The Monthly Weather Review - South Australia is produced twelve times each year by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology's South Australian Climate Services Centre. It is intended to provide a concise but informative overview of the temperatures, rainfall and significant weather events in South Australia for the month. To keep the Monthly Weather Review as timely as possible, much of the information is based on electronic reports. Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of these reports, the results can be considered only preliminary until complete quality control procedures have been carried out. Major discrepancies will be noted in later issues. We are keen to ensure that the Monthly Weather Review is appropriate to the needs of its readers. If you have any comments or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact us: By mail South Australian Regional Office South Australian Climate Services Centre Bureau of Meteorology 25 College Road KENT TOWN SA 5067 AUSTRALIA By telephone (08) 8366 2600 By email [email protected] You may also wish to visit the Bureau's home page, http://www.bom.gov.au. Units of measurement Except where noted, temperature is given in degrees Celsius (°C), rainfall in millimetres (mm), and wind speed in kilometres per hour (km/h). Observation times and periods Each station in South Australia makes its main observation for the day at 9 am local time. At this time, the precipitation over the past 24 hours is determined, and maximum and minimum thermometers are also read and reset. -

Master Plan Chapter 2 – Adelaide Airport Today

2 Adelaide Airport Today ADELAIDE AIRPORT / MASTER PLAN 2019 25 2.1. Background Adelaide Airport is the aviation gateway to Adelaide Adelaide Airport is operated by Adelaide Airport Ltd and South Australia and processed 8.5 million (AAL). Adelaide and Parafield Airports were transferred passengers in 2018. Passenger numbers have more from the Commonwealth Government to AAL in May than doubled since privatisation of the airport in 1998, 1998, with a 50-year lease for both airports and an with international passenger numbers more than option to extend the lease for a further 49 years. The quadrupling over this period to one million. lease requires AAL to operate the site as an airport, as well as allowing for other developments to support the With this growth in passenger movements, Adelaide economic viability of the airport. Airport’s significance to both Adelaide and South Australia continues to increase; not only in terms of As a significant private company in South Australia, being an essential passenger and freight hub situated AAL helps create vibrant communities and appreciates only six kilometres from the Adelaide CBD, but also as that commercial success is inseparable from the a major employment and business centre. responsibility to make a significant and positive contribution to the community and the State. Nearly Adelaide Airport’s location provides significant and 84 per cent of AAL shares are held by superannuation unique advantages: funds for the benefit of Australian citizens. AAL makes • Within six kilometres of the Adelaide CBD important contributions to organisations that benefit • Centrally located within the Adelaide the local and wider community, and the Adelaide metropolitan area Airport Community Investment Initiatives incorporates partnerships across various sectors including the • Well linked to nearby major sea and rail ports arts, business development, people empowerment • Well connected to major road corridors, connecting enterprises and remote emergency services. -

Australian Aviation Wildlife Statistics Bird and Animal Strikes 2001 to 2011

Australian aviation wildlife strike statisticsInsert document title LocationBird and animal| Date strikes 2002 to 2011 ATSB Transport Safety Report InvestigationResearch [InsertAviation Mode] Research Occurrence Report Investigation XX-YYYY-####AR-2012-031 Final ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Aviation Research and Analysis Report AR-2012-031 Final Australian aviation wildlife strike statistics: Bird and animal strikes 2002 to 2011 - i - Report No. AR-2012-031 Publication date 4 June 2012 ISBN 978-1-74251-265-5 Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2012 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to below as the Commonwealth). Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and all photos and graphics, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. A summary of the licence terms is available from http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en. -

An Investigation of Extreme Heatwave Events and Their Effects on Building and Infrastructure Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper #9

An investigation of extreme heatwave events and their effects on building and infrastructure Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper #9 Minh Nguyen, Xiaoming Wang and Dong Chen National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: An investigation of extreme heatwave events and their effects on building and infrastructure / Minh Nguyen ... [et al.]. ISBN: 978-0-643-10633-8 (pdf) Series: CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship working paper series; 9. Other Authors/ Xiaoming, Wang. Contributors: Dong Chen. Climate Adaptation Flagship. Enquiries Enquiries regarding this document should be addressed to: Dr Xiaoming Wang Urban System Program, CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems PO Box 56, Graham Road, Highett, VIC 3190, Australia [email protected] Dr Minh Nguyen Urban Water System Engineering Program, CSIRO Land & Water PO Box 56, Graham Road, Highett, VIC 3190, Australia [email protected] Enquiries about the Climate Adaptation Flagship or the Working Paper series should be addressed to: Working Paper Coordinator CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship [email protected] Citation This document can be cited as: Nguyen M., Wang X. and Chen D. (2011). An investigation of extreme heatwave events and their effects on building and infrastructure. CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship Working paper No. 9. http://www.csiro.au/resources/CAF-working-papers.html ii The Climate Adaptation Flagship Working Paper series The CSIRO Climate Adaptation National Research Flagship has been created to address the urgent national challenge of enabling Australia to adapt more effectively to the impacts of climate change and variability. This working paper series aims to: • provide a quick and simple avenue to disseminate high-quality original research, based on work in progress • generate discussion by distributing work for comment prior to formal publication.