NFL Hall of Fame, 50Th Anniversary by CHUCK SUCH Behind the Scenes…A Determined Force

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ice Bowl: the Cold Truth About Football's Most Unforgettable Game

SPORTS | FOOTBALL $16.95 GRUVER An insightful, bone-chilling replay of pro football’s greatest game. “ ” The Ice Bowl —Gordon Forbes, pro football editor, USA Today It was so cold... THE DAY OF THE ICE BOWL GAME WAS SO COLD, the referees’ whistles wouldn’t work; so cold, the reporters’ coffee froze in the press booth; so cold, fans built small fires in the concrete and metal stands; so cold, TV cables froze and photographers didn’t dare touch the metal of their equipment; so cold, the game was as much about survival as it was Most Unforgettable Game About Football’s The Cold Truth about skill and strategy. ON NEW YEAR’S EVE, 1967, the Dallas Cowboys and the Green Bay Packers met for a classic NFL championship game, played on a frozen field in sub-zero weather. The “Ice Bowl” challenged every skill of these two great teams. Here’s the whole story, based on dozens of interviews with people who were there—on the field and off—told by author Ed Gruver with passion, suspense, wit, and accuracy. The Ice Bowl also details the history of two legendary coaches, Tom Landry and Vince Lombardi, and the philosophies that made them the fiercest of football rivals. Here, too, are the players’ stories of endurance, drive, and strategy. Gruver puts the reader on the field in a game that ended with a play that surprised even those who executed it. Includes diagrams, photos, game and season statistics, and complete Ice Bowl play-by-play Cheers for The Ice Bowl A hundred myths and misconceptions about the Ice Bowl have been answered. -

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 -

Ben Lee Boynton:The Purple Streak

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 25, No. 3 (2003) Ben Lee Boynton:The Purple Streak by Jeffrey Miller The 1924 season was one of transition for Buffalo’s pro football team. The All-Americans, as the team had been known since its founding in 1920, had been very successful in its four year history, finishing within one game of the league championship in both the 1920 and 1921 seasons. But successive 5-4 campaigns and declining attendance had convinced owner Frank McNeil that it was time to get out of the football business. McNeil sold the franchise to a group led by local businessman Warren D. Patterson and Tommy Hughitt, the team’s player/coach, for $50,000. The new ownership changed the name of the team to Bisons, and committed themselves signing big name players in an effort to improve performance both on the field and at the box office. The biggest transaction of the off-season was the signing of “the Purple Streak,” former Williams College star quarterback Benny Lee Boynton. Boynton, a multiple All America selection at Williams, began his pro career with the Rochester Jeffersons in 1921. His signing with the Bisons in 1924 gave the Buffalo team its first legitimate star since Elmer Oliphant donned an orange and black sweater three years earlier. Born Benjamin Lee Boynton on December 6, 1898 in Waco, Texas, to Charles and Laura Boynton, Ben Lee learned his love of football at an early age. He entered Waco High School in 1912, and the next year began a string of three consecutive seasons and Waco’s starting quarterback. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE March 28, 2006 Mara Will Be Missed by Many and Was Ber of the Team

March 28, 2006 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE 4127 advocate for this resolution on the championships, and six National Football School and Fordham University in New House floor and hope my colleagues League championships, including the Super York City. will join me in honoring such a worthy Bowl XXI and Super Bowl XXV titles; During the early 1960s, Wellington cause today. Whereas the only time Mara was away and his brother Jack, the owners of the from the New York Giants was during World Mr. Speaker, I yield back the balance War II, when he served honorably in the NFL’s largest market, agreed to share of my time. United States Navy in both the Atlantic and television revenue on a league-wide Mr. DENT. Mr. Speaker, I urge all Pacific theaters and earned the rank of Lieu- basis, dividing the amounts of money Members to support adoption of H. Res. tenant Commander; available in cities like New York with 85, and I yield back the balance of my Whereas, in addition to his outstanding smaller market teams, like the Pitts- time. leadership of the New York Giants, Wel- burgh Steelers and the Green Bay The SPEAKER pro tempore (Mr. lington Mara also made outstanding con- Packers. This concept of revenue shar- tributions to the National Football League BRADLEY of New Hampshire). The ques- ing allowed the NFL to grow and is as a whole, including serving on its Execu- tion is on the motion offered by the tive Committee, Hall of Fame Committee, still being used today. gentleman from Pennsylvania (Mr. -

Protest at the Pyramid: the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2003 Protest at the Pyramid: The 1968 Mexico City Olympics and the Politicization of the Olympic Games Kevin B. Witherspoon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PROTEST AT THE PYRAMID: THE 1968 MEXICO CITY OLYMPICS AND THE POLITICIZATION OF THE OLYMPIC GAMES By Kevin B. Witherspoon A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2003 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Kevin B. Witherspoon defended on Oct. 6, 2003. _________________________ James P. Jones Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member _________________________ Valerie J. Conner Committee Member _________________________ Robinson Herrera Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project could not have been completed without the help of many individuals. Thanks, first, to Jim Jones, who oversaw this project, and whose interest and enthusiasm kept me to task. Also to the other members of the dissertation committee, V.J. Conner, Robinson Herrera, Patrick O’Sullivan, and Joe Richardson, for their time and patience, constructive criticism and suggestions for revision. Thanks as well to Bill Baker, a mentor and friend at the University of Maine, whose example as a sports historian I can only hope to imitate. Thanks to those who offered interviews, without which this project would have been a miserable failure: Juan Martinez, Manuel Billa, Pedro Aguilar Cabrera, Carlos Hernandez Schafler, Florenzio and Magda Acosta, Anatoly Isaenko, Ray Hegstrom, and Dr. -

New Years Resolutions

January 1, 2018 Soboba Indian Reporter: Ernie C. Salgado Jr., Publisher/Editor Fools Shooting At the Dark! New Years Resolutions As sad as it is, every New Years eve it Well folks it’s that time of to “Unreasonable.” Of seems like it’s a full moon as all the year again for us to make all course some of us are mental giants are out shooting at the those New Year Resolution. more disciplined and dark. hold the line of which I Some of the number one am not included, I tend They either don’t understand or know of resolutions are to drop those to be with the failed Isaac Newtons “Laws of Gravity” of extra pounds, cut down on memory group. what goes up must come down or simple sat and sugar, eat more veg- don’t care. Most likely the latter. etables, drink less soda The good thing is that we or beer, spend more time get to celebrate the start It just don’t make any sense for anyone with the kids and get that of another year. to take out a gun and shoot it into the sky annual doctors check up. not knowing where the bullets will come Happy New Year and may God bless down. Irresponsible at a minimum and Although our intentions are good our you and your family. beyond stupid not to mention cost at memory betrays us before the end of Soboba Indian Reporter about a buck a bullet. the month and we tend to chalk it up Mia Basquez-Gallerito His grandfather, Tony center in the photo Basquez (Pechanga) above with her son, served in the U.S. -

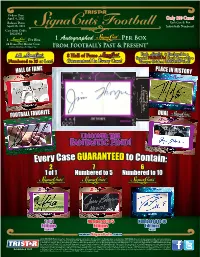

FB-Signcuts-Salesshe

Orders Due: April 4, 2012 Only 100 Cases! Release Date: Each Case & Box April 25, 2012 Individually Numbered! Case Item Code: I0025954 1 Per Box 1 Autographed Per Box 24 Boxes Per Master Case: 2 12-Box Mini Cases Per Master Case From Football’s Past & Present* Each is Enclosed in a All 8 Hall of Fame Special PREMIUM Card Case with a Numbered to 25 or Less! Guaranteed In Every Case! Tamper Evident TRISTAR® Seal! HALL OF FAME PLACE IN HISTORY DUAL FOOTBALL FAVORITE Uncover the Fantastic Find! 2 7 6 1 of 1 Numbered to 5 Numbered to 10 1 of 1 Numbered to 5 Numbered to 10 Editions Editions Editions (PURPLE) (RED) (BLUE) www.SignaCuts.comwww.SignaCuts.com ©2012 TRISTAR Productions, Inc. Information, pricing and product details subject to change prior to production. TRISTAR® does not, in any manner, make any representations as to the present or future value of these SignaCuts™. SignaCuts™ included are a random selection of autographs from current or former football players* and are not guaranteed to include any specific player, manufacturer, team or value. Any guarantees are over the entire production run. SignaCuts™ is a registered Trademark of TRISTAR® Productions, Inc. and is not affiliated with any football league(s), team(s), organization(s) or individual player(s). Any use of the name(s), of a football league(s), teams(s), organization(s) and/or player(s) is used for identification purposes only. This product is not sponsored by, endorsed by or affiliated with The Topps Company, Inc®, The Upper Deck Company, LLC®, Donruss Playoff LP®, Fleer/Skybox International LP® or any other trading card company. -

Chapter Eight

CHAPTER EIGHT PRO FOOTBALL’S EARLY YEARS Then all of a sudden this team was playing to 6,000–8,000 people. I personally think that the Oorang Indians, the Canton Bulldogs, and the Massillon Tigers were three teams that probably introduced people to pro football. — Robert Whitman. Professional football got its start long after pro baseball, and for many years was largely ignored by the general public. Prior to 1915, when Jim Thorpe signed with the Canton Bulldogs, there was little money in the game. The players earned less than was paid, under the table, to some allegedly amateur players on success- ful college teams. Jim Thorpe, 1920s jim thorpe association Things changed when Thorpe entered the pro game. Jack Cusack, the manager of the Canton Bulldogs, recalled: “I hit the jackpot by signing the famous Jim Thorpe … some of my business ‘advisers’ frankly predicted that I was leading the Bulldogs into bankruptcy by paying Jim the enormous sum of $250 a game, but the deal paid off even beyond my greatest expectations. Jim was an attraction as well as a player. Whereas our paid attendance averaged about 1,200 before we took him on, we filled the Massil- lon and Canton parks for the next two games — 6,000 for the first and 8,000 for the second. All the fans wanted to see the big Indian in action. On the field, Jim was a fierce competitor, absolutely fearless. Off the field, he was a lovable fellow, big-hearted and with a good sense of humor.” Unlike Thorpe’s experience in professional baseball, he was fully utilized on the gridiron as a running back, kicker, and fierce defensive player. -

Pro Football Hall of Fame

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME The Professional Football Hall Between four and seven new MARCUS ALLEN CLIFF BATTLES of Fame is located in Canton, members are elected each Running back. 6-2, 210. Born Halfback. 6-1, 195. Born in Ohio, site of the organizational year. An affirmative vote of in San Diego, California, Akron, Ohio, May 1, 1910. meeting on September 17, approximately 80 percent is March 26, 1960. Southern Died April 28, 1981. West Vir- 1920, from which the National needed for election. California. Inducted in 2003. ginia Wesleyan. Inducted in Football League evolved. The Any fan may nominate any 1982-1992 Los Angeles 1968. 1932 Boston Braves, NFL recognized Canton as the eligible player or contributor Raiders, 1993-1997 Kansas 1933-36 Boston Redskins, Hall of Fame site on April 27, simply by writing to the Pro City Chiefs. Highlights: First 1937 Washington Redskins. 1961. Canton area individuals, Football Hall of Fame. Players player in NFL history to tally High lights: NFL rushing foundations, and companies and coaches must have last 10,000 rushing yards and champion 1932, 1937. First to donated almost $400,000 in played or coached at least five 5,000 receiving yards. MVP, gain more than 200 yards in a cash and services to provide years before he is eligible. Super Bowl XVIII. game, 1933. funds for the construction of Contributors (administrators, the original two-building com- owners, et al.) may be elected LANCE ALWORTH SAMMY BAUGH plex, which was dedicated on while they are still active. Wide receiver. 6-0, 184. Born Quarterback. -

The Oorang Indians

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 3, No. 1 (1981) THE OORANG INDIANS By Bob Braunwart, Bob Carroll & Joe Horrigan GOING TO THE DOGS "Let me tell you about my big publicity stunt," wrote Walter Lingo, owner and operator of the Oorang Kennels in a 1923 edition of Oorang Comments, his monthly magazine devoted to singing the praises of himself and his Airedales. "You know Jim Thorpe, don't you, the Sac and Fox Indian, the world's greatest athlete, who won the all-around championship at the Olympic Games in Sweden in 1912? Well, Thorpe is in our organization." Lingo went on to explain that he had placed Thorpe in charge of an all-Indian football team that toured the country's leading cities for the express purpose of advertising Oorang Airedales. As far as Lingo was concerned, that was the only thing that really mattered -- how good Thorpe and company made his dogs look. Football was a game he never really cared for very much. Ironically, Lingo's "stunt" produced the most colorful collection of athletes ever to step onto an NFL gridiron. In American sports lore, there never was, and surely never will be again, anything like the Oorangs, the first, the last, and the only all-Indian team ever to play in a major professional sports league. Although Thorpe was given three full pages in Oorang Comments, very little was said about the performance of his team. It was just as well; they weren't very good, despite the presence of two future Hall of Famers and several other former All-Americans in their lineup. -

AFL-NFL Speak, Write, and Research Engage in Substantive Debate Become a Global Citizen

AHSMUN IV: AFL-NFL Speak, Write, and Research Engage in substantive debate Become a global citizen Chairs: Joseph Weisberg and Matthew Kirchmier AMERICAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE (AFL) & NATIONAL CORPORATE FOOTBALL LEAGUE (NFL) MERGER Introduction Many factors were at play in the 1960s as two professional football leagues started a duel for America’s viewership. The American Football League (AFL), founded in 1959, challenged the established National Football League (NFL) for viewership and fan loyalty. Riding on popular rules that promoted scoring, racial diversity, and robust personalities, the AFL’s success escalated tensions between the two leagues. As player values continued to rise, Pete Rozelle, Tex Schramm, and Lamar Hunt initiated a secret negotiation process that later came to involve all owners. Background In 1959, Lamar Hunt formed the AFL after the NFL rejected his desire for an expansion team. In its inaugural season, the AFL featured 8 teams: the Boston Patriots, Buffalo Bills, Houston Oilers, New York Titans, Dallas Texans, Denver Broncos, Los Angeles Chargers, and Oakland Raiders. Eventually, the AFL expanded to include the Miami Dolphins and Cincinnati Bengals. From the onset, the NFL sought to undermine the newly formed American League. In 1959, Hunt had agreed with an ownership group led by Max Winter to place an AFL franchise in the Twin Cities. Despite its public policy that it would not expand, the NFL offered the ownership group an expansion team in the older, more prestigious National Football League. To further subvert the new league, the NFL expanded to Dallas, which eventually prompted Lamar Hunt to move his Dallas Texans to their current home in Kansas City. -

15 Modern-Era Finalists for Hall of Fame Election Announced

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 11, 2013 Joe Horrigan at (330) 588-3627 15 MODERN-ERA FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION ANNOUNCED Four first-year eligible nominees – Larry Allen, Jonathan Ogden, Warren Sapp, and Michael Strahan – are among the 15 modern-era finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Selection Committee meets in New Orleans, La. on Saturday, Feb. 2, 2013. Joining the first-year eligible, are eight other modern-era players, a coach and two contributors. The 15 modern-era finalists, along with the two senior nominees announced in August 2012 (former Kansas City Chiefs and Houston Oilers defensive tackle Curley Culp and former Green Bay Packers and Washington Redskins linebacker Dave Robinson) will be the only candidates considered for Hall of Fame election when the 46-member Selection Committee meets. The 15 modern-era finalists were determined by a vote of the Hall’s Selection Committee from a list of 127 nominees that earlier was reduced to a list of 27 semifinalists, during the multi-step, year-long selection process. Culp and Robinson were selected as senior candidates by the Hall of Fame’s Seniors Committee. The Seniors Committee reviews the qualifications of those players whose careers took place more than 25 years ago. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. The Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee’s 17 finalists (15 modern-era and two senior nominees*) with their positions, teams, and years active follow: • Larry Allen – Guard/Tackle – 1994-2005 Dallas Cowboys; 2006-07 San Francisco 49ers • Jerome Bettis – Running Back – 1993-95 Los Angeles/St.