Dryopteris Affinis Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Vascular Plants Endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020

British & Irish Botany 2(3): 169-189, 2020 List of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020 Timothy C.G. Rich Cardiff, U.K. Corresponding author: Tim Rich: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 31st August 2020 Abstract A list of 804 plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands is broken down by country. There are 659 taxa endemic to Britain, 20 to Ireland and three to the Channel Islands. There are 25 endemic sexual species and 26 sexual subspecies, the remainder are mostly critical apomictic taxa. Fifteen endemics (2%) are certainly or probably extinct in the wild. Keywords: England; Northern Ireland; Republic of Ireland; Scotland; Wales. Introduction This note provides a list of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands, updating the lists in Rich et al. (1999), Dines (2008), Stroh et al. (2014) and Wyse Jackson et al. (2016). The list includes endemics of subspecific rank or above, but excludes infraspecific taxa of lower rank and hybrids (for the latter, see Stace et al., 2015). There are, of course, different taxonomic views on some of the taxa included. Nomenclature, taxonomic rank and endemic status follows Stace (2019), except for Hieracium (Sell & Murrell, 2006; McCosh & Rich, 2018), Ranunculus auricomus group (A. C. Leslie in Sell & Murrell, 2018), Rubus (Edees & Newton, 1988; Newton & Randall, 2004; Kurtto & Weber, 2009; Kurtto et al. 2010, and recent papers), Taraxacum (Dudman & Richards, 1997; Kirschner & Štepànek, 1998 and recent papers) and Ulmus (Sell & Murrell, 2018). Ulmus is included with some reservations, as many taxa are largely vegetative clones which may occasionally reproduce sexually and hence may not merit species status (cf. -

In the Fern Dryopteris Affinis Ssp. Affinis

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO Departamento de Biología de Organismos y Sistemas. Programa de Doctorado en Biogeociencias Apogamy in the fern Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis. Physiological and transcriptomic approach. Apogamia en el helecho Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis. De la fisiología a la transcriptómica. TESIS DOCTORAL Alejandro Rivera Fernández Directoras: Elena Fernández González y María Jesús Cañal Villanueva Oviedo 2020 RESUMEN DEL CONTENIDO DE TESIS DOCTORAL 1.- Título de la Tesis Español/Otro Idioma: Apogamia en el helecho Inglés: Apogamy in the fern Dryopteris affinis Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis: de la fisiología a la ssp. affinis: a physiological and transcriptomic transcriptómica approach 2.- Autor Nombre: Alejandro Rivera Fernández DNI/Pasaporte/NIE:53507888K Programa de Doctorado: BIOGEOCIENCIAS Órgano responsable: UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO RESUMEN (en español) Esta memoria de tesis aborda un estudio sobre el desarrollo vegetativo y reproductivo del gametofito helecho Dryopteris affinis ssp. affinis, cuyo ciclo vital cuenta con un caso peculiar de apomixis. En concreto, se informa de un enfoque fisiológico y transcriptómico, revelando un papel de las fitohormonas, ya sea mediante el análisis de los efectos causados por la adición al medio de cultivo, o midiendo los niveles endógenos, así como a través de perfiles 010 (Reg.2018) 010 - transcriptómicos comparativos entre gametofitos unidimensionales y bidimensionales. VOA La tesis consta de cinco capítulos: una introducción, tres trabajos experimentales y una - discusión general. En la introducción, se ofrece una visión general de la investigación llevada a MAT - cabo en helechos en los últimos años, para que el lector conciba una nueva idea sobre la contribución que este grupo vegetal puede ofrecer para profundizar en la reproducción de FOR plantas, y en el concreto, en la apomixis. -

(Polypodiales) Plastomes Reveals Two Hypervariable Regions Maria D

Logacheva et al. BMC Plant Biology 2017, 17(Suppl 2):255 DOI 10.1186/s12870-017-1195-z RESEARCH Open Access Comparative analysis of inverted repeats of polypod fern (Polypodiales) plastomes reveals two hypervariable regions Maria D. Logacheva1, Anastasiya A. Krinitsina1, Maxim S. Belenikin1,2, Kamil Khafizov2,3, Evgenii A. Konorov1,4, Sergey V. Kuptsov1 and Anna S. Speranskaya1,3* From Belyaev Conference Novosibirsk, Russia. 07-10 August 2017 Abstract Background: Ferns are large and underexplored group of vascular plants (~ 11 thousands species). The genomic data available by now include low coverage nuclear genomes sequences and partial sequences of mitochondrial genomes for six species and several plastid genomes. Results: We characterized plastid genomes of three species of Dryopteris, which is one of the largest fern genera, using sequencing of chloroplast DNA enriched samples and performed comparative analysis with available plastomes of Polypodiales, the most species-rich group of ferns. We also sequenced the plastome of Adianthum hispidulum (Pteridaceae). Unexpectedly, we found high variability in the IR region, including duplication of rrn16 in D. blanfordii, complete loss of trnI-GAU in D. filix-mas, its pseudogenization due to the loss of an exon in D. blanfordii. Analysis of previously reported plastomes of Polypodiales demonstrated that Woodwardia unigemmata and Lepisorus clathratus have unusual insertions in the IR region. The sequence of these inserted regions has high similarity to several LSC fragments of ferns outside of Polypodiales and to spacer between tRNA-CGA and tRNA-TTT genes of mitochondrial genome of Asplenium nidus. We suggest that this reflects the ancient DNA transfer from mitochondrial to plastid genome occurred in a common ancestor of ferns. -

BPS Cultivar Group

BPS Cultivar Group Issue 5 October 2018 Mark’s Musings One year of newsletters completed, I know it’s a sign of old age, but it seems to have gone very quickly. In this edition I have to give special thanks to two non-members, in the order they appear: John Ed- miston, Director of “Tropical Britain” and Christa Wardrup. John kindly allowed me to cut and paste from his site while Christa was the inspiration and source of photos for, what I hope, will be an on-going series on exotic cultivars Classic Cultivar Dryopteris affinis Cristata ‘The King’ This is a plant I am sure we all have, or have grown. A few years ago it was to be seen in just about every nursery and Garden Centre, then it seemed to disappear (certainly down here in the South east) except for the specialist nurseries. I had a plant for many years in my previous garden, when we moved and I dug it up to bring with me, it split into two crowns, sadly neither are doing very well here, in fact I have just moved one to, I hope, a better location. This has only one frond. The other crown has two “good” fronds and two very stunted fronds. This gave me a problem for this article as I couldn't use either for illustrations (I do have some pride!). I had a look on line and decided I was going to have to contact one of the nurseries to see if I could use their photos when my wife decided she wanted to go out for a while (as a fitness test after an opera- tion) We went to a local Hillier’s Gar- den Centre for coffee and, what do I find—they have several pots of ’The King’, so, just for you all, I bought the one you see on the left and on the next page. -

Dryopteris Filix-Mas (L.) Schott, in Canterbury, New Zealand

An Investigation into the Habitat Requirements, Invasiveness and Potential Extent of male fern, Dryopteris filix-mas (L.) Schott, in Canterbury, New Zealand A thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment Of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Forestry Science By Graeme A. Ure School of Forestry University of Canterbury June 2014 Table of Contents Table of Figures ...................................................................................................... v List of Tables ......................................................................................................... xi Abstract ................................................................................................................ xiii Acknowledgements .............................................................................................. xiv 1 Chapter 1 Introduction and Literature Review ............................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Taxonomy and ecology of Dryopteris filix-mas .......................................................... 2 1.2.1 Taxonomic relationships .................................................................................... 2 1.2.2 Life cycle ............................................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Native distribution .............................................................................................. 4 1.2.4 Native -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

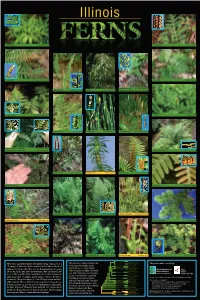

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

PSNS – Botanical Section – Bulletin 38 – 2015

PSNS Botanical PERTHSHIRE SOCIETY OF NATURAL SCIENCE BOTANICAL SECTION BULLETIN NO. 38 – 2015 Reports from 2015 Field Meetings, including Field Identification Excursions We look forward to seeing as many members on our excursions as possible, and any friends and family who would like to come along. All meetings are free to PSNS members, and new members are especially welcome. The field meetings programme is issued at the Section’s AGM in March, and is also posted on the PSNS website www.psns.org.uk. Six excursion days had been organised particularly to provide opportunities for field identification in different habitats, and one of these was given specifically to the identification of ferns. Over the six days there were 59 attendances, 352 different taxa of vascular plants were recorded and 768 records made and added to the database of the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. Most attendances were by members of the PSNS, including three new members who were attracted by the programme, and we were also joined by BSBI members. The popularity of these excursions proved that field identification is what many botanists at different levels of experience are looking for, and Perthshire provides a wide range of habitats to explore. There are not many opportunities for learning plant identification such as we have been able to provide. The accounts of these days appear below, along with those of the other excursions, numbered as in the programme. Location Date Attendances Records Taxa Taxa additions 1 Lady Mary’s Walk 15.04.2015 5 142 142 2 Thistle Brig 13.05.2015 9 171 57 4 Rumbling Bridge 10.06.2015 10 70 34 6 Creag an Lochain 08.07.2015 11 137 65 10 Doune Ponds 12.08.2015 8 92 21 10 Loch Watston 12.08.2015 6 137 27 12 Fern Day, Aberfoyle 09.08.2015 10 19 6 Totals 59 768 352 1. -

Dryopteris Carthusiana (Vill.) H.P

Dryopteris carthusiana (Vill.) H.P. Fuchs Dryopteris carthusiana toothed wood fern toothed wood fern Dryopteridaceae (Wood Fern Family) Status: State Review Group 1 Rank: G5S2? General Description: Adapted from the Flora of North America (1993): The stalk of this fern is ¼-1/3 the length of the leaf and scaly at the base. The fronds are light green, coarsely cut, relatively narrow, ovate-lanceolate in outline, and 6 to 30 in. (1.5-7.6 dm) long by 4 to 12 in. (1-3 dm) wide. The leaves are not persistent, except in years with mild winters. The leaflets are lanceolate-oblong; the lower leaflets are more lanceolate-triangular and are slightly reduced. The leaflet margins are serrate and the teeth spiny. Sori (spore clusters) are midway between the midvein and margin of segments. Identification Tips: Three other species of Dryopteris occur in this region, including D. arguta, D. filix-mas, and D. expansa, although only D. expansa has been found in association with D. carthusiana. D. carthusiana is distinguished from D. expansa by the color and shape of the frond. D. carthusiana has a duller, light green color, while D. expansa has a glossier, dark green frond color. D. carthusiana has a relatively narrow and ovate-lanceolate blade. D. expansa typically has a triangular shaped blade, with the lowest leaflets distinctly larger than succeeding pairs. The lowest leaflets of D. carthusiana blades are little, if any, larger than adjacent pairs and less deeply dissected than D. expansa tends to be. No hybrids between these two have been found. A technical key is recommended for identification. -

Ching (Acta Phytotax

Stusies in the Family Thelypteridaceae.III. A new system of genera in the Old World R.E. Holttum Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew scheme of classification in is based the examination The new presented this paper on which of all species in the family Thelypteridaceae I have been able to trace in the Old have of World. I gradually compiled a list about 700 names(basionyms) andhaveexamined other authentic material of all but small and in the of type or a proportion; course study of herbaria I have notedabout another which to be specimens in many 50 species appear undescribed. I have attempted to re-describeallthe previously-named species, noting char- acters not mentionedinexisting descriptions, especially the detaileddistribution of hairs and those the and stalk of and characters of is glands, including on body sporangia, spores. It that there some detected which refer probable remain published names, not yet by me, of the but I think there to species family, are not many. I have also made a study of all generic and infrageneric names which are typifiable of have tried and fix the by species Thelypteridaceae, and in doubtful cases I to clarify As in the second this series 18: typification. already reported paper of (Blumea 195 —215), I have had the help of Dr. U. Sen and Miss N. Mittrain examining anatomical and other microscopic characters of some type species, and hope to present further information of this kind later. the of As a beginning, I adopted generic arrangement Ching (Acta Phytotax. Sinica 8: with the exclusion of I does 289—335. -

Draft Ballina Biodiversity Plan

Draft Local Biodiversity Action Plan Ballina County Mayo Prepared by Woodrow Sustainable Solutions Ltd. for Mayo County Council April 2021 An Action of the County Mayo Heritage Plan 1 The Ballina Local Biodiversity Action Plan is an initiative of the Mayo County Council Heritage Office and was developed in consultation with local community organisations. Authorship This report was written by Philip Doddy. Philip is an ecologist at Woodrow Sustainable Solutions. He has completed a PhD in Aquatic Sciences, a BSc (Hons) in Freshwater and Marine Biology, and a Diploma in Amenity Horticulture. Philip carries out botanical monitoring, site surveys and habitat mapping, and compiles EcIAs, NISs, screening reports and vegetation monitoring reports. He has also carried out research on calcareous lakes and pools, microbial communities, and ecological succession. All Woodrow staff members are required to abide by a strict code of professional conduct in every aspect of their work. Philip Doddy – Qualifications: PhD – Aquatic Sciences, Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, 2019. BSc (Hons) – Freshwater and Marine Biology, Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, 2013. Diploma - Amenity Horticulture, Teagasc, National Botanic Gardens, 2001. Acknowledgements Thanks to all of the following for contributing in various ways: Deirdre Cunningham, Lynda Huxley, Chris Huxley, Mary Roberts, Ruth-Ann Leak, Michael Donlon, Martin Butler, Colm Madden. All photographs and figures are either the property of Woodrow Sustainable Solutions Ltd or subject to a Creative Commons license allowing free distribution, except where otherwise indicated. 2 Executive Summary This action plan for Ballina, Co. Mayo provides advice and guidance on practical and meaningful actions which can be taken by the local authority, community groups and individuals to protect and promote biodiversity in the Ballina area. -

Cutting Back Ferns – the Art of Fern Maintenance Richie Steffen

Cutting Back Ferns – The Art of Fern Maintenance Richie Steffen When I am speaking about ferns, I am often asked about cutting back ferns. All too frequently, and with little thought, I give the quick and easy answer to cut them back in late winter or early spring, except for the ones that don’t like that. This generally leads to the much more difficult question, “Which ones are those?” This exposes the difficulties of trying to apply one cultural practice to a complicated group of plants that link together a possible 12,000 species. There is no one size fits all rule of thumb. First of all, cutting back your ferns is purely for aesthetics. Ferns have managed for millions of years without being cut back by someone. This means that for ferns you may not be familiar with, it is fine to not cut them back and wait to see how they react to your growing conditions and climate. There are three factors to consider when cutting back ferns: 1. Is your fern evergreen, semi-evergreen, winter-green or deciduous? Deciduous ferns are relatively easy to decide whether to cut back – when they start to yellow and brown in the autumn, cut them to the ground. Some deciduous ferns have very thin fronds and finely divided foliage that may not even need to be cut back in the winter. A light layer of mulch may be enough to cover the old, withered fronds, and they can decay in place. Semi-evergreen types are also relatively easy to manage. -

Dryopteris Cristata (L.) A

Dryopteris cristata (L.) A. Gray crested shield-fern Dryopteridaceae - wood fern family status: State Sensitive, BLM sensitive, USFS sensitive rank: G5 / S2 General Description: A dapted from Flora of North A merica (1993+): Perennial fern with leaves clustered on a short rhizome. Leaves 35-70 x 8-12 cm, with both fertile and sterile forms. Fertile leaves larger, erect, dying back in winter; sterile leaves several, smaller, green through winter, spreading, forming a rosette. Petiole 1/4-1/3 the length of the leaf, scaly at least at the base, scales tan, scattered. Blade green, narrowly lanceolate or with parallel sides, pinnate-pinnatifid, not glandular. Pinnae of fertile leaves triangular, twisted to nearly perpendicular to the plane of the blade. Basal pinnules longer than adjacent pinnules. Pinnule margins with spiny teeth toward tip. Reproductive Characteristics: Sori round, in 1 row, located midway between the midvein and margin of pinnules. Indusia lacking glands, round to kidney-shaped. Fertile June to September. Identif ication Tips: D. arguta has glandular leaf blades that persist Illustration by Jeanne R. Janish, through the winter; the pinnules are finely spiny with spreading teeth. D. ©1969 University of Washington Press filix-mas leaves all die back in winter; they are 28-120 cm long, with petioles less than 1/4 the length of the leaves, and scales of 2 types (broad and hairlike). Identification may be complicated by the frequent presence of hybrids in the field. Range: Europe, southern C anada, WA , northern ID, northwest MT, ND, NE, MN south through MO , and much of the eastern U.S.