Reedbed HAP.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2007 2008

1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 1 Richmond Borough Mind Annual Report 1946 Mind Annual Report 6/10/08 11:15 Page 2 April 2007-March 2008 Achievements and Performance This has been another year of change, as the Recovery Approach was Carers Support & Training introduced throughout the statutory mental health services in Richmond, We welcome the new Carers Strategy 2007-2010, a challenge to us all in Richmond Borough Mind to adapt to new, more whose aims include improved well being and quality of life for carers; making sure their contribution is outward looking, positive and empowering ways of working. recognised; increasing choice, control and information and providing training for carers and professionals. We continued to shape our service so it has a key role in In line with our strategic aims, we sought to modernise As an organisation, we have become stronger in the realising these aims: investigating the use of Carers and diversify our services throughout the year, tailoring course of the year, securing income for more frequent Vouchers, increasing the resources of our information activities at our drop-ins to attract a wide spectrum of in-house support and training for our staff, and library; and making funding bids for well being sessions. service users and fundraising for resources to move into working to strengthen our infrastructure in order to new fields like TimeBanking, Befriending and work to employ a Finance Officer and an Administrative The three support groups continued to meet in support Peer-Support groups. Later in the year, we Assistant as well as volunteers. -

Isla Hoffmann-Heap Report Habitats Regulations Assessment for The

Habitats Regulations Assessment for the London Borough of Bromley's Proposed Submission Draft Local Plan London Borough of Bromley Project Number: 60474250 November 14 2016 Habitats Regulations Assessment for the London Borough of Bromley's Proposed Submission Draft Local Plan Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Isla Hoffmann-Heap Dr James Riley Max Wade Consultant Ecologist Associate Director Technical Director Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 0 15/11/16 Draft JR James Riley Associate Prepared for: London Borough of Bromley AECOM Habitats Regulations Assessment for the London Borough of Bromley's Proposed Submission Draft Local Plan Prepared for: London Borough of Bromley Prepared by: Isla Hoffmann-Heap Consultant Ecologist T: 01256 310 486 M: 07920 789 719 E: [email protected] AECOM Limited Midpoint Alencon Link Basingstoke Hampshire RG21 7PP UK T: +44(0)1256 310200 aecom.com © 2016 AECOM Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. Prepared for: London Borough of Bromley AECOM Habitats Regulations Assessment for the London Borough of Bromley's Proposed Submission Draft Local Plan Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. -

Waltham Forest Archaeological Priority Area Appraisal October 2020

London Borough of Waltham Forest Archaeological Priority Areas Appraisal October 2020 DOCUMENT CONTROL Author(s): Maria Medlycott, Teresa O’Connor, Katie Lee-Smith Derivation: Origination Date: 15/10/2020 Reviser(s): Tim Murphy Date of last revision: 23/11/2020 Date Printed: 23/11/2020 Version: 2 Status: Final 2 Contents 1 Acknowledgments and Copyright ................................................................................... 6 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 7 3 Explanation of Archaeological Priority Areas .................................................................. 8 4 Archaeological Priority Area Tiers ................................................................................ 10 5 History of Waltham Forest Borough ............................................................................. 13 6 Archaeological Priority Areas in Waltham Forest.......................................................... 31 6.1 Tier 1 APAs Size (Ha.) .......................................................................................... 31 6.2 Tier 2 APAs Size (Ha.) .......................................................................................... 31 6.3 Tier 3 APAs Size (Ha.) .......................................................................................... 32 6.4 Waltham Forest APA 1.1. Queen Elizabeth Hunting Lodge GV II* .................... 37 6.5 Waltham Forest APA 1.2: Water House ............................................................... -

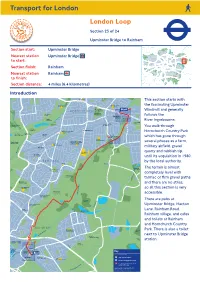

London Loop. Section 23 of 24

Transport for London. London Loop. Section 23 of 24. Upminster Bridge to Rainham. Section start: Upminster Bridge. Nearest station Upminster Bridge . to start: Section finish: Rainham. Nearest station Rainham . to finish: Section distance: 4 miles (6.4 kilometres). Introduction. This section starts with the fascinating Upminster Windmill and generally follows the River Ingrebourne. You walk through Hornchurch Country Park which has gone through several phases as a farm, military airfield, gravel quarry and rubbish tip, until its acquisition in 1980 by the local authority. The terrain is almost completely level with tarmac or firm gravel paths and there are no stiles, so all this section is very accessible. There are pubs at Upminster Bridge, Hacton Lane, Rainham Road, Rainham village, and cafes and toilets at Rainham and Hornchurch Country Park. There is also a toilet next to Upminster Bridge station. Directions. Leave Upminster Bridge station and turn right onto the busy Upminster Road. Go under the railway bridge and past The Windmill pub on the left. Cross lngrebourne River and then turn right into Bridge Avenue. To visit the Upminster Windmill continue along the main road for a short distance. The windmill is on the left. Did you know? Upminster Windmill was built in 1803 by a local farmer and continued to grind wheat and produce flour until 1934. The mill is only open on occasional weekends in spring and summer for guided tours, and funds are currently being raised to restore the mill to working order. Continue along Bridge Avenue to Brookdale Avenue on the left and opposite is Hornchurch Stadium. -

Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening Report – Draft Site Allocations

Report Submitted to Submitted by London Borough of Haringey AECOM Scott House Alençon Link Basingstoke Hampshire RG21 7PP United Kingdom Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening Report – Draft Site Allocations DPD AECOM Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening Report – Page i Draft Site Allocations DPD Prepared by: Isla Hoffmann Heap Checked by: James Riley Ecologist Associate Director Approved by: James Riley Associate Director Rev No Comments Checked Approved Date by by 0 Draft for Client Comments JR JR 02/11/15 1 Final for consultation JR JR 10/11/15 Scott House, Alençon Link, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG21 7PP, United Kingdom Telephone: 01256 310 200 Website: http://www.aecom.com 47076094 10/11/2015 London Borough of Haringey Council November/2015 AECOM Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening Report – Page ii Draft Site Allocations DPD Limitations AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of The London Borough of Haringey Council (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by AECOM. This Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client nor relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by AECOM has not been independently verified by AECOM, unless otherwise stated in the Report. -

Brent Valley & Barnet Plateau Area Framework All London Green Grid

All Brent Valley & Barnet Plateau London Area Framework Green Grid 11 DRAFT Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 9 Area Description 10 Strategic Context 11 Vision 14 Objectives 16 Opportunities 20 Project Identification 22 Clusters 24 Projects Map 28 Rolling Projects List 34 Phase One Early Delivery 36 Project Details 48 Forward Strategy 50 Gap Analysis 51 Recommendations 52 Appendices 54 Baseline Description 56 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA11 Links 58 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA11 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www.london.gov.uk/publication/all-london- green-grid-spg . Cover Image: View across Silver Jubilee Park to the Brent Reservoir Foreword 1 Introduction – All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology Introduction Area Frameworks Partnership - Working The various and unique landscapes of London are Area Frameworks help to support the delivery of Strong and open working relationships with many recognised as an asset that can reinforce character, the All London Green Grid objectives. -

LBR 2007 Front Matter V5.1

1 London Bird Report No.72 for the year 2007 Accounts of birds recorded within a 20-mile radius of St Paul's Cathedral A London Natural History Society Publication Published April 2011 2 LONDON BIRD REPORT NO. 72 FOR 2007 3 London Bird Report for 2007 produced by the LBR Editorial Board Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements – Pete Lambert 5 Rarities Committee, Recorders and LBR Editors 7 Recording Arrangements 8 Map of the Area and Gazetteer of Sites 9 Review of the Year 2007 – Pete Lambert 16 Contributors to the Systematic List 22 Birds of the London Area 2007 30 Swans to Shelduck – Des McKenzie Dabbling Ducks – David Callahan Diving Ducks – Roy Beddard Gamebirds – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Divers to Shag – Ian Woodward Herons – Gareth Richards Raptors – Andrew Moon Rails – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Waders – Roy Woodward and Tim Harris Skuas to Gulls – Andrew Gardener Terns to Cuckoo – Surender Sharma Owls to Woodpeckers – Mark Pearson Larks to Waxwing – Sean Huggins Wren to Thrushes – Martin Shepherd Warblers – Alan Lewis Crests to Treecreeper – Jonathan Lethbridge Penduline Tit to Sparrows – Jan Hewlett Finches – Angela Linnell Buntings – Bob Watts Appendix I & II: Escapes & Hybrids – Martin Grounds Appendix III: Non-proven and Non-submitted Records First and Last Dates of Regular Migrants, 2007 170 Ringing Report for 2007 – Roger Taylor 171 Breeding Bird Survey in London, 2007 – Ian Woodward 181 Cannon Hill Common Update – Ron Kettle 183 The establishment of breeding Common Buzzards – Peter Oliver 199 -

State of the Natural Environment in London: Securing Our Future

State of the natural environment in London: securing our future www.naturalengland.org.uk Contents Foreword 1 1 London’s natural environment 2 2 Natural London, Wild London 4 3 Natural London, Active London 12 4 Natural London, Future London 19 Annexes 25 © M a t h e w M a s s i n i Water vole Foreword The natural environment faces a number of This report on the state of the natural unique challenges in London that demand a environment in London shows there is much long term and sustainable response. work to do. It highlights Natural England’s position on some of the most crucial issues Perhaps the greatest challenge we face is to concerning the natural environment in ensure the benefits of the natural environment London. It describes how we will work with a are recognised and raised up the agenda at a range of people and organisations to deliver time when the global economy is centre our vision for Natural London, helping to stage. The natural environment underpins our ensure London is a world leader in improving health, wellbeing and prosperity. the environment. © We need to find ways of conserving and E l l e enhancing our green spaces and natural n S o assets in light of the knowledge that London f t l e is set to continue to grow for the foreseeable y future. We must take opportunities to connect more Londoners with their natural environment to encourage awareness of the benefits it can bring to health and quality of life. We need to quickly focus on how we are Alison Barnes going to adapt to the 50 years, at least, of Regional Director climate change that is now unavoidable. -

The Butterflies of North and West London

The butterflies of north and west London Andrew Wood & Leslie Williams This joint meeting with Butterfly conservation heard, firstly a presentation describing a tour through a fictional part of Middlesex recording every butterfly that occurs and comparing the situation now with that in the mid-1980s. In 1987, using records from 1980-86, reports were published on The butterflies of the London area and The butterflies of Hertfordshire. The presentation covered all London boroughs north of the Thames and west of the Lee Valley, which formerly formed parts of London, Hertfordshire and Middlesex. The area has a lot of very good habitats with a lot of green space including old cemeteries, brownfield sites and areas never built on such as parkland, woodland and farmland. Beginning in the winter, the first butterfly on the wing would be the Red admiral, which probably winters in Britain and each year’s butterflies are not all new immigrants as previously thought. It undergoes a diapause rather than hibernation, sheltering in ivy and other creepers and is active on warm winter days. It was fairly well distributed in the 1980s and is now more common virtually everywhere in north and west London. Red Admiral Comma Peacock In late February-early March, the Comma is the first of the true hibernators to emerge. It is active till late October-early November, feeding up for hibernation. Its distribution has not changed much, being common in the 1980s and common now. At about the same time, the Peacock emerges. It is generally in hibernation by late August, hibernation being governed by day-length rather than temperature. -

Outdoor Learning Providers in the Borough

Providers of Outdoor Learning in Richmond Environmental, Friends of Parks and Residents Groups Environment Trust Website: www.environmenttrust.co.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8891 5455 Contact: Stephen James Events are advertised on http://www.environmenttrust.co.uk/whats-on Friends of Barnes Common Website: www.barnescommon.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 07855 548 404 Contact: Sharon Morgan Events are advertised on www.barnescommon.org.uk/learning Friends of Bushy and Home Parks Website: www.fbhp.org.uk Email: [email protected] Events are advertised on www.fbhp.org.uk/walksandtalks Green Corridor Land based horticultural qualifications for young people aged 14-35. Website: www.greencorridor.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 01403 713 567 Contact: Julie Docking Updated March 2016 Friends of the River Crane Environment (FORCE) Website: www.force.org.uk Email: [email protected] For walks and talks, community learning, and outdoor learning for schools in sites in the lower Crane Valley see http://e-voice.org.uk/force/calendar/view Friends of Carlisle Park Website: http://e-voice.org.uk/friendsofcarlislepark/ Ham United Group Website: www.hamunitedgroup.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 2941 Contact: Penny Frost River Thames Boat Project Educational, therapeutic and recreational cruises and activities on the River Thames. Website: www.thamesboatproject.org Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8940 3509 Contact: Pippa Thames Explorer Trust Website: www.thames-explorer.org.uk Email: [email protected] Phone: 020 8742 0057 Contact: Lorraine Conterio or Simon Clarke Summer playscheme - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/families/summer-playscheme Foreshore walks - www.thames-explorer.org.uk/foreshore-walks/ YMCA London South West Website: www.ymcalsw.org Contact: Myke Catterall Updated March 2016 Thames Young Mariners Thames Young Mariners in Ham offer outdoor learning opportunities for schools, youth groups, families and adults all year round including day and residential visits. -

London Borough of Richmond Upon Thames Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 London Borough of Richmond Upon Thames

Official LONDON BOROUGH OF RICHMOND UPON THAMES ANTI-SOCIAL BEHAVIOUR, CRIME AND POLICING ACT 2014 LONDON BOROUGH OF RICHMOND UPON THAMES PUBLIC SPACES PROTECTION ORDER 2020 (DOG CONTROL) The Council of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames (in this Order called “the Council”) hereby makes the following Order pursuant to Section 59 of the Anti- social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 (“the Act”). This Order may be cited as the “London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Public Spaces Protection Order 2017 (Dog Control)”. This Order came into force on 16 October 2017 and lasted for a period of 3 years from that date. This Order was extended, pursuant to section 60 of the Act, for a period of 3 years from 2020. This Order can be extended pursuant to section 60 of the Act. In this Order the following definitions apply: “Person in charge” means the person who has the dog in his possession, care or company at the time the offence is committed or, if none, the owner or person who habitually has the dog in his possession. “Restricted area” means the land described and/or shown in the maps in the Schedule to this Order. “Authorised officer” means a police officer, PCSO, Council officer, and persons authorised by the Council to enforce this Order. "Assistance dog" means a dog that is trained to aid or assist a disabled person. The masculine includes the feminine. The Offences Article 1 - Dog Fouling If within the restricted area, a dog defecates, at any time, and the person who is in charge of the dog fails to remove the faeces from the restricted area forthwith, that person shall be guilty of an offence unless – a. -

Richmond's Hidden Gems

Richmond’s Hidden Gems Richmond is rich in world renowned gems. You can discover royal history at Hampton Court Palace, traverse the stunning diversity of Kew Gardens and get up close and personal with wild deer in Richmond Park; and yet Richmond has many hidden gems just waiting to be discovered around the next corner. The following itinerary is perfect if you want to get away from established tourist attractions and explore some of Richmond’s best kept secrets. A morning stroll in Crane Park Crane Park follows the path of the River Crane between Twickenham and Whitton as far as Hounslow Heath. Often overshadowed by the Royal Parks in the borough, Crane Park possesses a fascinating nature reserve set against the backdrop of an old Shot Tower and pleasant riverside walks. Crane Park Island, the nature reserve is a mixture of interesting woodland, reedbeds and scrub habitats that are home to a number of different types of wildlife including the endangered water vole and from time to time the majestic kingfisher. A path intersperses these interesting habitats allowing you to get close enough to have a chance of seeing the wildlife but not so close as to be intrusive. After visiting the nature reserve and inspecting the Shot Tower, you can follow the river path towards Twickenham eventually emerging in the area close to the Harlequins Rugby Stadium, from here it is a moderate walk into Twickenham for lunch. Further information about the park is available here Lunch in Twickenham and exploring York House Gardens Rest your weary legs with lunch in Twickenham which has a wide variety of pubs, cafes and restaurants to relax and recuperate in.