Bengal .District Gazetteers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nadia Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/56 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL HOGALBERIA ADARSHA AYADANGA SHIKSHANIKETAN, ROAD,HOGALBARIA HOGALBERIA ADARSHA 1 123204713031 ABHIJIT SARKAR NADIA 19101007604 VILL+P.O- NADIA M SC NONE 49 23 72 ,HOGALBARIA , SHIKSHANIKETAN HOGOLBARIA DIST- NADIA 741122 NADIA W.B, PIN- 741122 KARIMPUR JAGANNATH HIGH BATHANPARA,KARI ABHIK KUMAR KARIMPUR JAGANNATH SCHOOL, VILL+P.O- 2 123204713013 MPUR,KARIMPUR , NADIA 19101001003 NADIA M GENERAL NONE 72 62 134 BISWAS HIGH SCHOOL KARIMPUR DIST- NADIA 741152 NADIA W.B, PIN- 741152 CHAKDAHA RAMLAL MAJDIA,MADANPUR, CHAKDAHA RAMLAL ACADEMY, P.O- 3 123204703069 ABHIRUP BISWAS CHAKDAHA , NADIA NADIA 19102500903 NADIA M GENERAL NONE 68 72 140 ACADEMY CHAKDAHA PIN- 741245 741222, PIN-741222 KRISHNAGANJ,KRIS KRISHNAGANJ A.S HNAGANJ,KRISHNA KRISHNAGANJ A.S HIGH HIGH SCHOOL, 4 123204705011 ABHISHEK BISWAS NADIA 19100601204 NADIA M SC NONE 59 54 113 GANJ , NADIA SCHOOL VILL=KRISHNAGANJ, 741506 PIN-741506 KAIKHALI HARITALA BAGULA PURBAPARA HANSKHALI HIGH SCHOOL, VILL- BAGULA PURBAPARA 5 123204709062 ABHRAJIT BOKSHI NADIA,HARITALA,HA NADIA 19101211705 BAGULA PURBAPARA NADIA M SC NONE 74 56 130 HIGH SCHOOL NSKHALI , NADIA P.O-BAGULA DIST - 741502 NADIA, PIN-741502 SUGAR MILL GOVT MODEL SCHOOL ROAD,PLASSEY GOVT MODEL SCHOOL NAKASHIPARA, PO 6 123204714024 ABU SOHEL SUGAR NADIA 19100322501 NADIA M GENERAL NONE 66 39 105 NAKASHIPARA BETHUADAHARI DIST MILL,KALIGANJ , NADIA, PIN-741126 NADIA 741157 CHAKDAHA RAMLAL SIMURALI,CHANDUR CHAKDAHA RAMLAL ACADEMY, P.O- 7 123204702057 ADIPTA MANDAL IA,CHAKDAHA , NADIA 19102500903 NADIA M SC NONE 67 46 113 ACADEMY CHAKDAHA PIN- NADIA 741248 741222, PIN-741222 NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.2/56 GOVT. -

National Ganga River Basin Authority (Ngrba)

NATIONAL GANGA RIVER BASIN AUTHORITY (NGRBA) Public Disclosure Authorized (Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized Volume I - Environmental and Social Analysis March 2011 Prepared by Public Disclosure Authorized The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi i Table of Contents Executive Summary List of Tables ............................................................................................................... iv Chapter 1 National Ganga River Basin Project ....................................................... 6 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Ganga Clean up Initiatives ........................................................................... 6 1.3 The Ganga River Basin Project.................................................................... 7 1.4 Project Components ..................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.1 Objective ...................................................................................................... 8 1.4.1.2 Sub Component A: NGRBA Operationalization & Program Management 9 1.4.1.3 Sub component B: Technical Assistance for ULB Service Provider .......... 9 1.4.1.4 Sub-component C: Technical Assistance for Environmental Regulator ... 10 1.4.2.1 Objective ................................................................................................... -

II Block in Nadia District, West Bengal, India

www.ijird.com April, 2015 Vol 4 Issue 4 ISSN 2278 – 0211 (Online) The Role of Beels in Flood Mitigation- A Case Study of Krishnanagar- II Block in Nadia District, West Bengal, India Dr. Balai Chandra Das Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Krishnanagar Govt. College, Krishnanagar, West Bengal, India Sanat Das Assistant Teacher, Department of Geography, Bablari Ramsundar High School (H.S), Nabadwip, West Bengal, India Abstract: Selected Beels (wetlands) of C. D. Block Krishnagar-II cover an area of 385.99 acres or 1562046.11 m2 or 1.56 km2. With an average depth of 1.81 meter they can provide scope for 3776155.383 m3 flood water. They provide space for spread of flood water over a vast area reducing the vertical level as well as the vulnerability of flood disaster. This spread of flood water over a vast area facilitates recharge of ground water, which again reduces the flood level. Spills acts as arteries and veins to transport silt laden flood water to Beels during flood and silt-free water during lean periods. These processes help in maintaining river depth of rivers and hasty pass of flood water again reducing the flood level. There are 11 wetlands (Recorded under B.L. & L.R.O, Krishnagar-II), having an average area more or equal to 5 acres or 20234.28 m2 have been considered for the present study. Data for this study were collected from the office of the B.L. & L.R.O, Krishnagar-II, District Fishery Office, Nadia and simple arithmetic calculation is made to come into conclusion that healthy Beels are worthy means for flood mitigation. -

“Temple of My Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal's

“Temple of my Heart”: Understanding Religious Space in Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshi Community Aditya N. Bhattacharjee School of Religious Studies McGill University Montréal, Canada A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts August 2017 © 2017 Aditya Bhattacharjee Bhattacharjee 2 Abstract In this thesis, I offer new insight into the Hindu Bangladeshi community of Montreal, Quebec, and its relationship to community religious space. The thesis centers on the role of the Montreal Sanatan Dharma Temple (MSDT), formally inaugurated in 2014, as a community locus for Montreal’s Hindu Bangladeshis. I contend that owning temple space is deeply tied to the community’s mission to preserve what its leaders term “cultural authenticity” while at the same time allowing this emerging community to emplace itself in innovative ways in Canada. I document how the acquisition of community space in Montreal has emerged as a central strategy to emplace and renew Hindu Bangladeshi culture in Canada. Paradoxically, the creation of a distinct Hindu Bangladeshi temple and the ‘traditional’ rites enacted there promote the integration and belonging of Bangladeshi Hindus in Canada. The relationship of Hindu- Bangladeshi migrants to community religious space offers useful insight on a contemporary vision of Hindu authenticity in a transnational context. Bhattacharjee 3 Résumé Dans cette thèse, je présente un aperçu de la communauté hindoue bangladaise de Montréal, au Québec, et surtout sa relation avec l'espace religieux communautaire. La thèse s'appuie sur le rôle du temple Sanatan Dharma de Montréal (MSDT), inauguré officiellement en 2014, en tant que point focal communautaire pour les Bangladeshis hindous de Montréal. -

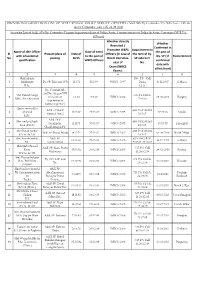

Gradation List of WBPS Officers 2019.Xlsx

PROVISIONAL GRADATION LIST OF WEST BENGAL POLICE SERVICE OFFICERS (Addl. SPs/Dy.Commdts./ Dy. S.Ps/Asstt. CPs & Asstt. Commdts. ) AS ON 01-05-2019 Seniority List of Addl. SPs/Dy. Commdts./Deputy Superintendents of Police/Asstt. Commissioners of Police & Asstt. Commdts.(W.B.P.S. Officers) Whether directly Whether Recruited / Confirmed in Promotee WBPS Appointment in Name of tlhe Officer Date of entry the post of Sl. Present place of Date of Officers (In case of the rank of Dy. with educational to the post of Dy. SP ( If Home District No. posting Birth Direct Recruitee SP vide G.O. qualification WBPS Officers confirmed year of No. date with Exam.(WBCS effect from) Exam.) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Shri Jayanta 138 - P.S. - Cell 1 Mukherjee Dy. SP, Telecom, WB 3.12.72 15.2.99 WBCS - 1997 Dated 14.12.2007 Kolkata B.Sc. 3.2.99. Dy. Commdt. IR. 2nd Bn., Siliguri WB Shri Rakesh Singh 956-P.S.Cell dt. 2 (to work on 5.5.72 8.8.06 WBCS-2004 08.08.2008 Hooghly MSC, Bio Chemistry 29.6.06 deputation to Kalimpong Dist.) Quazi Samsuddin Addl. SP.Rural 488-P.S.Cell dtd. 3 Ahamed 11.03.77 27.03.07 WBCS-2005 27.03.09 Malda Howrah Rural 20.3.07. M.Sc. Addl. DCP. Shri Amlan Ghosh 488-P.S.Cell dtd. 4 Serampore, 11.11.73 30.03.07 WBCS-2005 30.03.09 Jalpaiguri M.A.(Part I) 20.3.07. Chandannagar PC Shri Dipak Sarkar 488-P.S.Cell dtd. -

Impact on the Life of Common People for the Floods in Coloneal Period (1770 Ad-1900Ad) & Recent Time (1995 Ad-2016 Ad): a Case Study of Nadia District, West Bengal

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) IMPACT ON THE LIFE OF COMMON PEOPLE FOR THE FLOODS IN COLONEAL PERIOD (1770 AD-1900AD) & RECENT TIME (1995 AD-2016 AD): A CASE STUDY OF NADIA DISTRICT, WEST BENGAL. Ujjal Roy Research Scholar (T.M.B.U), Department of Geography. Abstract: Hazard is a harmful incident for human life which can destroy so many precious things like crops, houses, cattle, others wealth like money, furniture, valuable documents and human lives also. So many hazards are happens like earthquake, tsunamis, drought, volcanic eruption, floods etc for natural reasons. Global warming, human interferences increase those incidents of hazard. Flood is a one of the hazard which basically happens for natural reason but human interferences increase the frequency and depth of this which is very destructive for human society. Nadia is a historically very famous district lies between 22053’ N and 24011’ N latitude and longitude from 88009 E to 88048 E, covering an area of 3,927 square km under the State of West Bengal in India but regular incidents of floods almost every year in time of monsoon is a big problem here. Unscientific development works from British Period hamper the drainage systems of Nadia and create many incidents of flood in colonial period. Still now millions of people face this problem in various blocks of Nadia. Development in scientific way, preservation of water bodies & river, dig new ponds & canals, increase awareness programme between publics, modernise flood warning system, obey the safety precaution rules in time of flood can save the people from this hazard. -

A Case Study on Murshidabad District, West Bengal, India

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Physical Set-up and Agricultural Condition after Independence - A case study on Murshidabad District, West Bengal, India. Iman Sk Assistant Teacher in Geography Vivekananda Palli Kishore Bharati High School, Behala, Kolkata ABSTRACT Agriculture is the process of producing food, feed, fiber and many other desired products by the cultivation of certain plants and the raising of domesticated animals (livestock) that controlled by the climatic condition, nature of topography and socio economic demands of any area. Agricultural pattern is perhaps the clearest indicator for the management and modification of natural environment into cultural environment. The present paper is an attempt to analyze physical set-up and agricultural condition after independence - a case study on murshidabad district, west bengal, india and also to explore the agricultural production of land with different natural and socio-economic parameters for sustainable development. Based on the block wise secondary data obtained from the Bureau of Applied Economics and Statistics, Govt. of West Bengal, I prepared the soil coverage mapping of the area that shows the cropping pattern of study area. The results show that jute is the main agricultural production than others agricultural production. In 2015-16 total production of jute is 1939800 tonne, where paddy and wheat productiona sre 1120900 tonne and 285600 tonne. However, a planned agricultural pattern is suggested considering demographic change of the region. Keywords: Topography, soil type, drainage, agriculture pattern and GDP. INTRODUCTION Agriculture, as the backbone of Indian economy, plays the most crucial role in the socioeconomic sphere of the country. -

Research Paper Zoology Abundance of Pisces and Status of Water of Mathabhanga- Churni River in Indo-Bangla Border Region

Volume-3, Issue-7, July-2014 • ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Research Paper Zoology Abundance of Pisces and Status of Water of mathabhanga- Churni River in Indo-Bangla Border Region. Bidhan Chandra Research Scholar (Assistant Professor, Govt. K. C. College, Bangladesh) Fisheries and Aquaculture Extension Laboratory Department Of Zoology, Biswas University Of Kalyani,Kalyani-741235, Nadia, West Bengal, India. Ashis kumar Associate professor,Fisheries and Aquaculture Extension Laboratory Department Of Zoology, University Of Kalyani,Kalyani-741235, Nadia, West Panigrahi Bengal, India. ABSTRACT Measurement of water quality parameters plays a vital role in determining the pollutional load and correctness of a particular water body for aquatic organisms. The present investigations was carried out to measure the physiochemical parameters of Mathabhanga- Churni river in Indo-Bangla Border region to assess the pollution status for a period of one year from June 2012-to May 2013. The calculated physiochemical parameters revealed that the average ranges of Temperature, pH, DO, BOD, COD, Hardness, Alkalinity, Nitrate, Organic carbon and Freeco2 were 33.150c and 19.260c, 8.4 and 6.4, 5.1mg/l and 0.88mg/l, 46mg/l and 2.04mg/l, 420mg/l and 250mg/l, 660mg/l and 322mg/l, 560mg/l 380, 95mg/l and0.99 mg/l, 54mg/l and 16.4mg/l, 22mg/l and 05mg/l respectively. The results obtained from study showed that the measured parameters exhibit a great seasonal variation in different months of the year during the investigation and showed great difference in standard criteria of water quality indicates huge pollution effect on aquatic organisms especially on fish faunal diversity.33 fishes were identified during the investigation from one year and most of the species were carps and cat fishes. -

1 Manik Das S/O-Naresh Das, Vill-Tantla Roy Para, PO-Tatla, PS

Application for New Contract Carriage Permits of Auto-Rickshaw Meeting to be held on 14.01.2020 Memo No. 38(668)/MV Dt. 09.01.2020 Sl. Name & Address of the applicant No. 1 Manik Das S/O-Naresh Das, Vill-Tantla Roy para, P.O-Tatla, P.S-Chakdaha, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741222 2 Manojit Das S/O-Manik Das, Vill-Tantla Raypara, P.O-Tantla, P.S-Chakdaha, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741222 3 Soma Chanda S/O-Subhra Chanda, Vill-Dayalnagar, P.O-Nasra, Ranaghat, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741202 4 Hossain Mandal S/O-Zamsher Mandal, Vill-Paschin Gopinathpur, P.S-Tehatta, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741155 5 Sahidul Shekh S/O-Saheb Ali Shekh, Vill-Shyamnagar, P.O-Berij, P.S-Kotwali, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741103 Mahadeb Ball S/O-Bijay Krishna Ball, Vill-Natungram, P.O-Nrisinghapur, P.S-Santipur, Dist.-Nadia, Pin- 6 741404 7 Aparna Chakraborty S/O-Debasish Chakraborty, Vill+ P.O+ P.S-Taherpur, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741159 8 Tapan Biswas S/O-Madhusudan Biswas, Vill+ P.O-Ulashi, P.S-Hanskhali, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741502 Sukanta Biswas S/O-Paritosh Biswas, Vill-Pakhiura, P.O-Kumari Ramnagar, P.S-Hanskhali, Dist.-Nadia, 9 Pin-741502 Puspa Mondal S/O-Sufal Mondal, Vill-Ulashi Paschimpara, P.O-Ulashi, P.S-Hanskhali, Dist.-Nadia, Pin- 10 741502 11 Dilip Biswas S/O-Madhusudan Biswas, Vill+ P.O-Ulashi, P.S-Hanskhali, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741502 12 Pintu Saha S/O-Nimai Ch.Saha, Vill-Gournagar, P.O-Bagula, P.S-Hanskhali, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741502 13 Sujit Biswas S/O-Subhas Biswas, Vill-Khanpara, P.O-Birnagar, P.S-Taherpur, Dist.-Nadia, Pin-741127 Bhakta Das S/O-Bimal Das, Vill-Chandpur Paschimpara, P.O-chandanpur, -

A Case Study in Nadia District of West Bengal

INTERNATIONALJOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARYEDUCATIONALRESEARCH ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2020); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:1(6), January :2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in IMPACT OF REFUGEE: A CASE STUDY IN NADIA DISTRICT OF WEST BENGAL Alok Kumar Biswas Assistant Professor, Department of History Vivekananda College, Madhyamgram, Kolkata Nadia or ‘Naudia’ is famous for its literature, cultural heritage, and historical importance and after all partition and change its demographic features. Brahmin Pandits were associated with intellectual literature discuss knowledge, to do religious oblation and worship. The city was fully surrounded by dense bamboo and marsh forest and tigers, wild pigs, foxes etc used live in this forest. This was the picture of Nadia during the end of 18th century.i There was a well-known rhyme- “Bamboo, box and pond, three beauties of Nadia”. Here ‘Nad’ means Nadia or Nabadwip.ii This district was established in 1786. During the partition, Nadia district was also divided. However, according to Lord Mountbatten’s plan 1947 during partition of India the whole Nadia district was attached with earlier East Pakistan. This creates a lot of controversy. To solve this situation the responsibility was given to Sir Radcliff According to his decision three subdivisions of Nadia district (Kusthia, Meherpur and Chuadanga) got attached with East Pakistan on 18th August, naming Kusthia district and the remaining two sub-divisions (Krishnagar and Ranaghat) centered into India with the name Nabadwip earlier which is now called Nadia. While studying the history of self-governing rule of Ndai district one can see that six municipalities had been established long before independence. -

Minutes of 32Nd Meeting of the Cultural

1 F.No. 9-1/2016-S&F Government of India Ministry of Culture **** Puratatav Bhavan, 2nd Floor ‘D’ Block, GPO Complex, INA, New Delhi-110023 Dated: 30.11.2016 MINUTES OF 32nd MEETING OF CULTURAL FUNCTIONS AND PRODUCTION GRANT SCHEME (CFPGS) HELD ON 7TH AND 8TH MAY, 2016 (INDIVIDUALS CAPACITY) and 26TH TO 28TH AUGUST, 2016 AT NCZCC, ALLAHABAD Under CFPGS Scheme Financial Assistance is given to ‘Not-for-Profit’ Organisations, NGOs includ ing Soc iet ies, T rust, Univ ersit ies and Ind iv id ua ls for ho ld ing Conferences, Seminar, Workshops, Festivals, Exhibitions, Production of Dance, Drama-Theatre, Music and undertaking small research projects etc. on any art forms/important cultural matters relating to different aspects of Indian Culture. The quantum of assistance is restricted to 75% of the project cost subject to maximum of Rs. 5 Lakhs per project as recommend by the Expert Committee. In exceptional circumstances Financial Assistance may be given upto Rs. 20 Lakhs with the approval of Hon’ble Minister of Culture. CASE – I: 1. A meeting of CFPGS was held on 7 th and 8th May, 2016 under the Chairmanship of Shri K. K. Mittal, Additional Secretary to consider the individual proposals for financial assistance by the Expert Committee. 2. The Expert Committee meeting was attended by the following:- (i) Shri K.K. Mittal, Additional Secretary, Chairman (ii) Shri M.L. Srivastava, Joint Secretary, Member (iii) Shri G.K. Bansal, Director, NCZCC, Allahabad, Member (iv ) Dr. Om Prakash Bharti, Director, EZCC, Kolkata, Member, (v) Dr. Sajith E.N., Director, SZCC, Thanjavur, Member (v i) Shri Babu Rajan, DS , Sahitya Akademi , Member (v ii) Shri Santanu Bose, Dean, NSD, Member (viii) Shri Rajesh Sharma, Supervisor, LKA, Member (ix ) Shri Pradeep Kumar, Director, MOC, Member- Secretary 3. -

State Statistical Handbook 2014

STATISTICAL HANDBOOK WEST BENGAL 2014 Bureau of Applied Economics & Statistics Department of Statistics & Programme Implementation Government of West Bengal PREFACE Statistical Handbook, West Bengal provides information on salient features of various socio-economic aspects of the State. The data furnished in its previous issue have been updated to the extent possible so that continuity in the time-series data can be maintained. I would like to thank various State & Central Govt. Departments and organizations for active co-operation received from their end in timely supply of required information. The officers and staff of the Reference Technical Section of the Bureau also deserve my thanks for their sincere effort in bringing out this publication. It is hoped that this issue would be useful to planners, policy makers and researchers. Suggestions for improvements of this publication are most welcome. Tapas Kr. Debnath Joint Administrative Building, Director Salt Lake, Kolkata. Bureau of Applied Economics & Statistics 30th December, 2015 Government of West Bengal CONTENTS Table No. Page I. Area and Population 1.0 Administrative Units in West Bengal - 2014 1 1.1 Villages, Towns and Households in West Bengal, Census 2011 2 1.2 Districtwise Population by Sex in West Bengal, Census 2011 3 1.3 Density of Population, Sex Ratio and Percentage Share of Urban Population in West Bengal by District 4 1.4 Population, Literacy rate by Sex and Density, Decennial Growth rate in West Bengal by District (Census 2011) 6 1.5 Number of Workers and Non-workers