Characters in Arctostaphylos Taxonomy Author(S): Jon E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Haven Garden Plant List - 2010

PALM HAVEN GARDEN PLANT LIST - 2010 BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME Achillea millefolium 'Paprika' Paprika yarrow Arctostaphylos glauca big berry manzanita Arctostaphylos pajaroensis Pajaro manzanita Arctostaphylos uva-ursi bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi 'San Bruno Mountain' San Bruno Mountain bearberry Aristolochia californica California pipevine Artemisia pycnocephala coastal sagewort Baccharis pilularis 'Twin Peaks' Twin Peaks dwarf coyote brush Berberis aquifolium 'Golden Abundance' Golden Abundance Oregon-grape Carex spissa San Diego sedge Ceanothus 'Joyce Coulter' Joyce Coulte wild lilac Ceanothus arboreus feltleaf ceanothus Ceanothus gloriosus var exaltatus 'Emily Brown' Emily Brown glory brush Dendromecon harfordii Channel Island tree poppy Epilobium canum California fuchsia Erigeron glaucus seaside daisy Eriogonum fasciculatum California buckwheat Eriogonum latifolium coast buckwheat Eriogonum umbellatum sulfur flower Eriophyllum confertiflorum golden yarrow Heteromeles arbutifolia toyon Heterotheca sessilifolora false goldenaster Iris douglasiana Douglas iris Leymus condensatus 'Canyon Prince' Canyon Prince giant wild rye Mimulus aurantiacus sticky monkeyflower Monardella villosa coyote mint Mulhenbergia rigens deer grass Penstemon heterophyllus foothill penstemon Physocarpus capitatus ninebark Rhamnus californica 'Ed Holm' Ed Holm coffeeberry Rhamnus californica 'Mound San Bruno' Mound San Bruno coffeeberry Salvia clevelandii Cleveland sage Salvia mellifera 'Shirley's Creeper' Shirley's Creepe sage Salvia sonomensis 'Bee's Bliss' Bee's Bliss sage Satureja douglasii yerba buena Trichostema lanatum wolly blue curls Typha angustifolia narrow-leaved cattail Verbena lilacina lilac verbena Vitis californica 'Roger's Red' Roger's Red California wild grape. -

Conservation of Ectomycorrhizal Fungi: Exploring the Linkages Between Functional and Taxonomic Responses to Anthropogenic N Deposition

fungal ecology 4 (2011) 174e183 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/funeco Conservation of ectomycorrhizal fungi: exploring the linkages between functional and taxonomic responses to anthropogenic N deposition E.A. LILLESKOVa,*, E.A. HOBBIEb, T.R. HORTONc aUSDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Houghton, MI 49931, USA bComplex Systems Research Center, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03833, USA cState University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Department of Environmental and Forest Biology, 246 Illick Hall, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA article info abstract Article history: Anthropogenic nitrogen (N) deposition alters ectomycorrhizal fungal communities, but the Received 12 April 2010 effect on functional diversity is not clear. In this review we explore whether fungi that Revision received 9 August 2010 respond differently to N deposition also differ in functional traits, including organic N use, Accepted 22 September 2010 hydrophobicity and exploration type (extent and pattern of extraradical hyphae). Corti- Available online 14 January 2011 narius, Tricholoma, Piloderma, and Suillus had the strongest evidence of consistent negative Corresponding editor: Anne Pringle effects of N deposition. Cortinarius, Tricholoma and Piloderma display consistent protein use and produce medium-distance fringe exploration types with hydrophobic mycorrhizas and Keywords: rhizomorphs. Genera that produce long-distance exploration types (mostly Boletales) and Conservation biology contact short-distance exploration types (e.g., Russulaceae, Thelephoraceae, some athe- Ectomycorrhizal fungi lioid genera) vary in sensitivity to N deposition. Members of Bankeraceae have declined in Exploration types Europe but their enzymatic activity and belowground occurrence are largely unknown. -

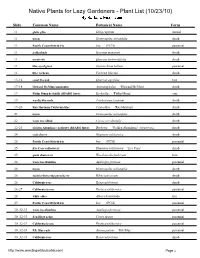

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10)

Native Plants for Lazy Gardeners - Plant List (10/23/10) Slide Common Name Botanical Name Form 11 globe gilia Gilia capitata annual 11 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 11 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 11 goldenbush Isocoma menziesii shrub 11 scrub oak Quercus berberidifolia shrub 11 blue-eyed grass Sisyrinchium bellum perennial 11 lilac verbena Verbena lilacina shrub 13-16 coast live oak Quercus agrifolia tree 17-18 Howard McMinn man anita Arctostaphylos 'Howard McMinn' shrub 19 Philip Mun keckiella (RSABG Intro) Keckiella 'Philip Munz' ine 19 woolly bluecurls Trichostema lanatum shrub 19-20 Ray Hartman California lilac Ceanothus 'Ray Hartman' shrub 21 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 22 western redbud Cercis occidentalis shrub 22-23 Golden Abundance barberry (RSABG Intro) Berberis 'Golden Abundance' (MAHONIA) shrub 2, coffeeberry Rhamnus californica shrub 25 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 25 Eve Case coffeeberry Rhamnus californica '. e Case' shrub 25 giant chain fern Woodwardia fimbriata fern 26 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 26 toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 26 fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 26 California rose Rosa californica shrub 26-27 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 28 white alder Alnus rhombifolia tree 29 Pacific Coast Hybrid iris Iris (PCH) perennial 30 032-33 western columbine Aquilegia formosa perennial 30 032-33 San Diego sedge Carex spissa perennial 30 032-33 California fescue Festuca californica perennial 30 032-33 Elk Blue rush Juncus patens '.l1 2lue' perennial 30 032-33 California rose Rosa californica shrub http://www weedingwildsuburbia com/ Page 1 30 032-3, toyon Heteromeles arbutifolia shrub 30 032-3, fuchsia-flowering gooseberry Ribes speciosum shrub 30 032-3, Claremont pink-flowering currant (RSA Intro) Ribes sanguineum ar. -

Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies Bracteata 10 1G Abutilon Palmeri 1 1G Acaena Pinnatifida Var

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 76 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2016 **FINAL**PLANT SALE LIST **FINAL** (9/30/2016 @ 6:00 PM) visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, OCTOBER 1, 2016 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name 6 1G Abies bracteata 10 1G Abutilon palmeri 1 1G Acaena pinnatifida var. californica 18 1G Achillea millefolium 10 4" Achillea millefolium - Black Butte 28 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' 8 4" Achillea millefolium 'Rosy Red' - donated by Annie's Annuals 2 4" Achillea millefolium 'Sonoma Coast' 7 4" Acmispon (Lotus) argophyllus var. argenteus 9 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) 25 4" Adiantum x tracyi (A. jordanii x A. aleuticum) 5 1G Aesculus californica 1 2G Agave shawii var. shawii 2 1G Agoseris grandiflora 8 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 2 2G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia 5 4" Ambrosia pumila 5 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia 9 1G Anemopsis californica 5 1G Angelica hendersonii 3 1G Angelica tomentosa 1 1G Apocynum androsaemifolium x Apocynum cannabinum 7 1G Apocynum cannabinum 5 1G Aquilegia formosa 2 4" Aquilegia formosa 4 4" Arbutus menziesii 2 1G Arctostaphylos andersonii 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata 3 1G Arctostaphylos 'Austin Griffith' 11 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 5 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Leading Botanists in San Diego Nancy Carol Carter

Journal of the California Garden & Landscape History Society Vol. 14, No. 4 • Fall 2011 The Brandegees: Leading Botanists in San Diego Nancy Carol Carter [This article, originally published in The Journal of San Diego History, is reprinted here, by permission, in a somewhat abridged form.1] he most renowned botanical couple of 19th-century and generally agreeing with his scientific principles, the T America lived in San Diego from 1894 until 1906. Brandegees eventually claimed a superior ability to classify They were early settlers in the Bankers Hill area, initially and appropriately name the plants they had collected and constructing a brick herbarium to house the world’s best observed in situ. Fully aware of delays and impatient with private collection of plant specimens from the western the imprecision of more distant classification work, both United States and Mexico. They lived in a tent until their resisted the tradition of submitting new species to Gray or treasured plant collection was properly protected, then built other East Coast scientists for botanical description.3 They a house connected to the herbarium. Around their home became expert taxonomists who described and defended they established San Diego’s first botanical garden—a col- their science in West Coast journals. During their lifetimes, lection of rare and exotic plants that furthered their research the Brandegees published a combined total of 159 scientific and delighted visitors. papers.4 Their example in- Botanists and plant ex- spired other Pacific Coast perts from around the botanists to greater confidence world knew of this garden in their own field experience and traveled to San Diego and the value of botanically to study its plants. -

Other Botanical Resource Assessment

USDA Forest Service Tahoe National Forest District Yuba River Ranger District OTHER BOTANICAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT Yuba Project 08/01/2017 Prepared by: Date: Courtney Rowe, District Botanist TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 TNF Watch List Botanical Species ........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Summary of Analysis Procedure .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Project Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 2 2 Special Status Plant Communities ....................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 2.2 Project Compliance ..................................................................................................................... 5 3 Special Management Designations ..................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6 3.2 Project Compliance .................................................................................................................... -

Propagation and Cultivation of Arctostaphylos in Relation to the Environment in Its Natural Habitat 291

Propagation and Cultivation of Arctostaphylos in Relation to the Environment in its Natural Habitat 291 Propagation and Cultivation of Arctostaphylos in Relation to the Environment in its Natural Habitat in California, U.S.A.© Lucy Hart' School of Horticulture, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB U.K. INTRODUCTION The Mary Helliar Travel Scholarship helped to fund a visit to California to study native plants in their natural habitats and in cultivation. Throughout my study I observed Arctostaphylos, commonly known as manzanita, growing naturally and was able to relate the natural habitats to cultivation conditions in botanic gardens and commercial nurseries where I learnt about the propagation and production of members of the genus. Arctostaphylos is a fundamental genus to California, found almost exclusively in the state, with different species occupying a range of habitats. It is a member of the Ericaceae and is closely related to Arbutus, sharing the same subfamily, Arbutoideae. The generic name is derived from two Greek words — arktos meaning bear and stuphule, a grape. The common name, manzanita (popularly used in California today) is Spanish for "little apple" from the appearance of its berry. There are approximately 60 species, of which several have many subspecies due to frequent hybridisations within the genus (Stuart and Sawyer, 2001). This can make identification difficult in areas where species ranges overlap. Schmidt (1973), a manzanita enthusiast, describes her excitement regarding the future possibilities for more horticultural forms from the natural hybridisations, as a "tantalising prospect." KEY HORTICULTURAL FEATURES The genus includes many forms of evergreen, woody shrubs ranging from low, prostrate, mat-forming types to a few which approach tree size. -

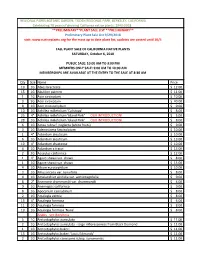

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Guidelines for Determining Significance and Report Format and Content Requirements

COUNTY OF SAN DIEGO GUIDELINES FOR DETERMINING SIGNIFICANCE AND REPORT FORMAT AND CONTENT REQUIREMENTS BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES LAND USE AND ENVIRONMENT GROUP Department of Planning and Land Use Department of Public Works Fourth Revision September 15, 2010 APPROVAL I hereby certify that these Guidelines for Determining Significance for Biological Resources, Report Format and Content Requirements for Biological Resources, and Report Format and Content Requirements for Resource Management Plans are a part of the County of San Diego, Land Use and Environment Group's Guidelines for Determining Significance and Technical Report Format and Content Requirements and were considered by the Director of Planning and Land Use, in coordination with the Director of Public Works on September 15, 2O1O. ERIC GIBSON Director of Planning and Land Use SNYDER I hereby certify that these Guidelines for Determining Significance for Biological Resources, Report Format and Content Requirements for Biological Resources, and Report Format and Content Requirements for Resource Management Plans are a part of the County of San Diego, Land Use and Environment Group's Guidelines for Determining Significance and Technical Report Format and Content Requirements and have hereby been approved by the Deputy Chief Administrative Officer (DCAO) of the Land Use and Environment Group on the fifteenth day of September, 2010. The Director of Planning and Land Use is authorized to approve revisions to these Guidelines for Determining Significance for Biological Resources and Report Format and Content Requirements for Biological Resources and Resource Management Plans except any revisions to the Guidelines for Determining Significance presented in Section 4.0 must be approved by the Deputy CAO. -

Arctostaphylos Hispidula, Gasquet Manzanita

Conservation Assessment for Gasquet Manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) Within the State of Oregon Photo by Clint Emerson March 2010 U.S.D.A. Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I. Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Author CLINT EMERSON is a botanist, USDA Forest Service, Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest, Gold Beach and Powers Ranger District, Gold Beach, OR 97465 TABLE OF CONTENTS Disclaimer 3 Executive Summary 3 List of Tables and Figures 5 I. Introduction 6 A. Goal 6 B. Scope 6 C. Management Status 7 II. Classification and Description 8 A. Nomenclature and Taxonomy 8 B. Species Description 9 C. Regional Differences 9 D. Similar Species 10 III. Biology and Ecology 14 A. Life History and Reproductive Biology 14 B. Range, Distribution, and Abundance 16 C. Population Trends and Demography 19 D. Habitat 21 E. Ecological Considerations 25 IV. Conservation 26 A. Conservation Threats 26 B. Conservation Status 28 C. Known Management Approaches 32 D. Management Considerations 33 V. Research, Inventory, and Monitoring Opportunities 35 Definitions of Terms Used (Glossary) 39 Acknowledgements 41 References 42 Appendix A. Table of Known Sites in Oregon 45 2 Disclaimer This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile existing published and unpublished information for the rare vascular plant Gasquet manzanita (Arctostaphylos hispidula) as well as include observational field data gathered during the 2008 field season. This Assessment does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service (Region 6) or Oregon/Washington BLM. Although the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. -

Oak Resources Management Plan

EXHIBIT A El Dorado County Oak Resources Managenient Plan September 2017 El Dorado County Community Development Agency Long Range Planning Division 2850 Fairlane Court, Placerville, CA 95667 OAK RESOURCES MANAGEMENT PLAN Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................... l 1.1 Purpose ...................................................................................................................1 1.2 Goals and Objectives of Plan .................................................................................2 1.3 Oak Resources in El Dorado County .....................................................................3 1.3.1 Oak Woodlands ........................................................................................... .3 1.3 .2 Oak Trees .................................................................................................... .4 1.4 Economic Activity, Land, and Ecosystem Values of Oak Resources ....................4 1.5 State-level Regulations ...........................................................................................4 2.0 Oak Resources Impact Mitigation Requirements .........................................................6 2.1 Applicability, Exemptions and Mitigation Reductions ..........................................6 2.1.1 Single-Family Lot Exemption...................................................................... 6 2.1.2 Fire Safe Activities Exemption ....................................................................6 -

Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences (4)5

PROCEEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA Academy of Sciences FOURTH SERIES Vol. V 1915 OS" SAN P^RANCISCO PUBLISHED BY THE ACADEMY 1915 COMMITTEE ON PUBLICATION George C. Edwards, Chairman C. E. Grunsky Barton Warren Evermann, Editor CONTENTS OF VOLUME V. Plates 1-19. PAGE Title-page i Contents iii Report of the President of the Academy for the Year 1914. By C. E. Grunsky 1 (Published March 26, 1915) Report of the Director of the Museum for the Year 1914. By Barton Warren Evermann - 1 1 (Published March 26, 1915) Fauna of the Type Tejon : Its Relation to the Cowlitz Phase of the Tejon Group of Washington. By Roy E. Dickerson. (Plates 1-11) 33 (Published June 15, 1915) A List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Utah, with Notes on the Species in the Collection of the Academy. By John Van Den- burgh and Joseph R. Slevin. (Plates 12-14) 99 (Published June 15, 1915) Description of a New Subgenus (Arborimus) of Phenacomys, with a Contribution to Knowledge of the Habits and Distribution of Phenacomys longicaudus True. By Walter P. Taylor. (Plate 15) 1 1 1 (Published December 30, 1915) Tertiary Deposits of Northeastern Mexico. By E. T. Durable. (Plates 16-19) 163 (Published December 31, 1915) Report of the President of the Academy for the Year 1915. By C. E. Grunsky 195 (Published May 4, 1916) Report of the Director of the Museum for the Year 1915. By Barton Warren Evermann 203 (Published May 4, 1916) Index 225, 232 July 19, 1916 / f / ^3 F»ROCEDEDINGS OF THE CALIFORNIA ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Fourth Series Vol.