A Journey Down the Rodge Brook Through the Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Mary Toms Warder

Mary Toms Warder (1795-1850) the first Bible Christian missionary to the Isle of Wight The Bible Christian Church was a Methodist denomination founded in 1815 by William O’Bryan, a Wesleyan Methodist preacher, in North Cornwall. Controversially, they allowed females to preach. Mary Toms was born in 1795 at Tintagel, Cornwall. At age 16, Mary was strong, vigorous, and active, reportedly she "feared and cared for nothing" and when visiting an Aunt in Plymouth she chanced to hear a Methodist preacher. From then she worshiped with the Methodists until around the age of 22 when Mary was attracted to the Bible Christian church and in 1820 began her work as a preacher where she travelled from town to town throughout the local circuit. Often encountering opposition, it was a hard life for a woman preacher as Mary was then operating in a society when at that time few women achieved leadership roles of any kind. Although never having visited there, she had a conviction she was being called to serve on the Isle of Wight, so in July 1823 now aged 27 Mary sailed from Plymouth to the Island, arriving at Cowes where she reported “Oh, could you see the sins committed here”. Starting to preach at East Cowes, soon two of the local Wesleyan preachers joined Mary which enabled her to travel further into the Island. The cosy alliance between the Established Church and the Landed Gentry was about to be challenged. Soon Mary was overwhelmed with invitations to preach in other parts of the Island and began conducting open air services and helping to establish numerous Bible Christian societies. -

Gurnard Film Society Little Voice Friday 7Th March 7.30 P.M

2 LETTER FROM ALL SAINTS’ 27 Most of us can find the first three months of the year slightly depressing. The colour and excitement of Christmas is behind us and before the coming of spring we could be faced with at least three months of grim weather. The poet John Clare however, in his book the Shepherd’s Calendar, found the months of February and March to be a time of looking forward to spring and a time of inspiration. He did however spend periods of time in various asylums in the Northampton area! In his poem February he writes;- A calm of pleasure listens round And almost whispers winter bye While fancy dreams of summer sounds And quiet rapture fills the eye This year March will be when the season of Lent begins. Christians use this period of time to prepare for the season of Easter, which for many marks the season of spring. Having just spent the last week in January accompanying my wife whilst she photographed various birds and animals on the Island I know the signs of spring are all around us. We were surprised to find a squirrel looking for food down a track in the West Wight and although we returned to the same point several times we didn’t see it again. He must have eaten, seen the rain and gone back to sleep. The ducks show every sign that spring isn’t far away and are preparing for a future generation of birds. But for all the spring signs, the colour in the countryside has that pastel quality that is found only in winter. -

Schedule 2019 24/06/19 2 23/12/19 OFF

Mobile Library Service Weeks 2019 Mobile Mobile Let the Library come Library Library w / b Week w / b Week Jan 01/01/19 HLS July 01/07/19 HLS to you! 07/01/19 HLS 08/07/19 HLS 14/01/9 1 15/07/19 1 21/01/19 2 22/07/19 2 28/01/19 HLS 29/07/19 HLS Feb 04/02/19 HLS Aug 05/08/19 HLS 11/02/19 1 12/08/19 1 18/02/19 2 19/08/19 2 25/02/19 HLS 26/08/19* HLS Mar 04/03/19 HLS Sept 02/09/19 HLS 11/03/19 1 09/09/19 1 18/03/19 2 16/09/19 2 25/03/19 HLS 23/09/19 OFF April 01/04/19 HLS 30/09/19 HLS 08/04/19 1 Oct 07/10/19 15/04/19 2 14/10/19 22/04/19 OFF 21/10/19 29/04/19 HLS 28/10/19 May 06/05/19* HLS Nov 04/11/19 13/05/19 1 11/11/19 20/05/19 2 18/11/19 OFF 27/05/19* OFF 25/11/19 June 03/06/19 HLS Dec 02/12/19 10/06/19 1 09/12/19 17/06/19 HLS 16/12/19 Schedule 2019 24/06/19 2 23/12/19 OFF 06/05/19—May Day Bank Holiday 27/05/19—Whitsun Bank Holiday 26/08/19—August Bank Holiday The Home Library Service (HLS) operates on weeks when the Mobile Library is not on the road. -

Scheme of Polling Districts As of June 2019

Isle of Wight Council – Scheme of Polling Districts as of June 2019 Polling Polling District Polling Station District(s) Name A1 Arreton Arreton Community Centre, Main Road, Arreton A2 Newchurch All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch A3 Apse Heath All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch AA Ryde North West All Saints Church Hall, West Street, Ryde B1 Binstead Binstead Methodist Schoolroom, Chapel Road, Binstead B2 Fishbourne Royal Victoria Yacht Club, 91 Fishbourne Lane BB1 Ryde South #1 5th Ryde Scout Hall, St Johns Annexe, St Johns Road, Ryde BB2 Ryde South #2 Ryde Fire Station, Nicholson Road C1 Brading Brading Town Hall, The Bull Ring, High Street C2 St. Helens St Helens Community Centre, Guildford Road, St. Helens C3 Bembridge North Bembridge Village Hall, High Street, Bembridge C4 Bembridge South Bembridge Methodist Church Hall, Foreland Road, Bembridge CC1 Ryde West#1 The Sherbourne Centre, Sherbourne Avenue CC2 Ryde West#2 Ryde Heritage Centre, Ryde Cemetery, West Street D1 Carisbrooke Carisbrooke Church Hall, Carisbrooke High Street, Carisbrooke Carisbrooke and Gunville Methodist Schoolroom, Gunville Road, D2 Gunville Gunville DD1 Sandown North #1 The Annexe, St Johns Church, St. Johns Road Sandown North #2 - DD2 Yaverland Sailing & Boating Club, Yaverland Road, Sandown Yaverland E1 Brighstone Wilberforce Hall, North Street, Brighstone E2, E3 Brook & Mottistone Seely Hall, Brook E4 Shorwell Shorwell Parish Hall, Russell Road, Shorwell E5 Gatcombe Chillerton Village Hall, Chillerton, Newport E6 Rookley Rookley Village -

WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP of the WIGHT Experience Sustainable Transport

BE A WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP OF THE WIGHT Experience sustainable transport Portsmouth To Southampton s y s rr Southsea Fe y Cowe rr Cowe Fe East on - ssenger on - Pa / e assenger l ampt P c h hi Southampt Ve out S THE EGYPT POINT OLD CASTLE POINT e ft SOLENT yd R GURNARD BAY Cowes e 5 East Cowes y Gurnard 3 3 2 rr tsmouth - B OSBORNE BAY ishbournFe de r Lymington F enger Hovercra Ry y s nger Po rr as sse Fe P rtsmouth/Pa - Po e hicl Ve rtsmouth - ssenger Po Rew Street Pa T THORNESS AS BAY CO RIVE E RYDE AG K R E PIER HEAD ERIT M E Whippingham E H RYDE DINA N C R Ve L Northwood O ESPLANADE A 3 0 2 1 ymington - TT PUCKPOOL hic NEWTOWN BAY OO POINT W Fishbourne l Marks A 3 e /P Corner T 0 DODNOR a 2 0 A 3 0 5 4 Ryde ssenger AS CREEK & DICKSONS Binstead Ya CO Quarr Hill RYDE COPSE ST JOHN’S ROAD rmouth Wootton Spring Vale G E R CLA ME RK I N Bridge TA IVE HERSEY RESERVE, Fe R Seaview LAKE WOOTTON SEAVIEW DUVER rr ERI Porcheld FIRESTONE y H SEAGR OVE BAY OWN Wootton COPSE Hamstead PARKHURST Common WT FOREST NE Newtown Parkhurst Nettlestone P SMALLBROOK B 4 3 3 JUNCTION PRIORY BAY NINGWOOD 0 SCONCE BRIDDLESFORD Havenstreet COMMON P COPSES POINT SWANPOND N ODE’S POINT BOULDNOR Cranmore Newtown deserted HAVENSTREET COPSE P COPSE Medieval village P P A 3 0 5 4 Norton Bouldnor Ashey A St Helens P Yarmouth Shaleet 3 BEMBRIDGE Cli End 0 Ningwood Newport IL 5 A 5 POINT R TR LL B 3 3 3 0 YA ASHEY E A 3 0 5 4Norton W Thorley Thorley Street Carisbrooke SHIDE N Green MILL COPSE NU CHALK PIT B 3 3 9 COL WELL BAY FRES R Bembridge B 3 4 0 R I V E R 0 1 -

Isle of Wight Record Office

GB0189MDR Isle of Wight Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 24556 The National Archives ISLE OF WIGHT COUNTY RECORD OFFICE ISLE OF WIGHT METHODIST RECORDS i The documents deposited under the headings 80/1 and 80/47 comprise almost all the records of Isle of Wight Methodism that are known still to exist. 80/1 was deposited by the Rev. Renouf, Super intendant of the West Wight Methodist Circuit, 80/47 by Rev. P. K. Parsons, Superintendent of the East Wight Circuit. A further deposit of West Wight material was made by Rev. A. Dodd of Totland Bay; this collection is now included with 80/1. This basic territorial division into East and West Wight, though it dates only from the Methodist unification of 1933-4, has been maintained in the scheduling of the minute and account books and miscellaneous papers. In detail the method of scheduling adopted has been to make a distinction between local circuit records and the records of individual chapels. Below these two classes a further distinction has been made between the Wesleyan Methodists, the Bible Christians (known as United Methodists from 1909) and the Primitive Methodists. For ease of access the registers, so often called for in the Record Office Search Room, have been listed together as MDR/--, . though with the distinction between circuits and individual chapels and between the various connections still.maintained. Only one "oddity" has come to light amongst these documents namely the United Methodist Free Church at West Cowes. -

Carisbrooke and Gunville Ward Nomination Paper Pack

Returning Officer Claire Shand _____________________________________________________________________________ From Clive Joynes County Hall, Newport, Isle of Wight, PO30 1UD Tel (01983) 823380 Email [email protected] DX 56361 Newport (Isle of Wight) Web iwight.com Election of a Parish Councillor for Newport and Carisbrooke Community Council - Carisbrooke and Gunville ward Nomination Paper Pack Please find enclosed a Nomination Paper pack as requested. The pack contains the following items: Nomination Paper Consent to Nomination Home Address Forms Political Party Certificate of Authority and Emblem Request form Election Timetable Section 80 Local Government Act 1972 Declaration of Secrecy Candidate Guide Notice of Withdrawal Notice of Appointment of Polling Agents Notice of Appointment of Counting Agents Notice of Appointment of Agents to attend the Opening of Postal Voters' Ballot Box To be a candidate at the above election the nomination paper, home address form and consent to nomination must be delivered by hand to the Returning Officer, County Hall, Newport, Isle of Wight, PO30 1UD, by 4:00 PM on Friday 9th July 2021. Please ensure that all relevant forms are fully completed, including all electoral letters and numbers where required. If elected, members of Parish and Town Councils are required to complete a register of interests and this will be p ublished on the Isle of Wight Council website and the website of the relevant Parish or Town Council. If you require any further information or assistance, please -

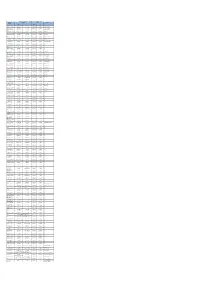

Planning and Infrastructure Services

PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES The following planning applications and appeals have been submitted to the Isle of Wight Council and can be viewed online www.iow.gov.uk/planning using the Public Access link. Alternatively they can be viewed at Seaclose Offices, Fairlee Road, Newport, Isle of Wight, PO30 2QS. Office Hours: Monday – Thursday 8.30 am – 5.00 pm Friday 8.30 am – 4.30 pm Comments on the applications must be received within 21 days from the date of this press list, and comments for agricultural prior notification applications must be received within 7 days to ensure they be taken into account within the officer report. Comments on planning appeals must be received by the Planning Inspectorate within 5 weeks of the appeal start date (or 6 weeks in the case of an Enforcement Notice appeal). Details of how to comment on an appeal can be found (under the relevant LPA reference number) at www.iow.gov.uk/planning. For householder, advertisement consent or minor commercial (shop) applications, in the event of an appeal against a refusal of planning permission, representations made about the application will be sent to Planning Inspectorate, and there will be no further opportunity to comment at appeal stage. Should you wish to withdraw a representation made during such an application, it will be necessary to do so in writing within 4 weeks of the start of an appeal. All written representations relating to applications will be made available to view online. PLEASE NOTE THAT APPLICATIONS WHICH FALL WITHIN MORE THAN ONE PARISH OR WARD WILL APPEAR ONLY ONCE IN THE LIST UNDER THE PRIMARY PARISH PRESS LIST DATE: 4th October 2019 NEW APPEALS LODGED Those persons having submitted written representations in respect of any of the applications now the subject of an appeal listed below will be notified in writing of the appeal within 7 days. -

ROAD OR PATH NAME from to from to Bouna Vista Path, Ventnor Entire Length Entire Length 28.10.2020 30.10.2020 Filming

ROAD AND PATH CLOSURES (19th October 2020 ‐ 25th October 2020) ROAD OR LOCATION DATE DETAILS PATH NAME FROM TO FROM TO Bouna Vista Path, Ventnor Entire length Entire length 28.10.2020 30.10.2020 Filming on the highway Dudley Road, Ventnor Entire length Entire length 28.10.2020 30.10.2020 Filming on the highway Bonchurch Village Road, Bonchurch Shute Trinity Road 26.10.2020 26.100.2020 Filming on the highway Ventnor Colwell Chine Road, Totland Colwell Common Road Colwell Road 26.10.2020 28.10.2020 CCTV Survey Burnt House Lane, Newport Great East Standen Farm Little East Standen Farm 28.10.2020 30.10.2020 Carriageway repairs Beaconsfield Road, Ventnor Entire length Entire length 26.10.2020 28.11.2020 Utility works Fraser Path, Cowes Entire length Entire length 26.10.2020 26.10.2020 Vegetation maintenance Whiteoak Lane, Porchfield Town Lane Underwood Lane 27.10.2020 27.10.2020 Vegetation maintenance Newnham Lane, Binstead Newnham Road Ryde Footpath 4 26.10.2020 29.10.2020 Utility works High Street, Brading New Road Cross Street 28.10.2020 29.10.2020 Frame and cover repairs Forest Road, Newport Parkhurst Road Gunville Road 16.10.2020 27.11.2020 CIP Newport Road, Ventnor Gills Cliff Road Down Lane 16.10.2020 27.11.2020 CIP Steephill Down Road, Entire length Entire length 16.10.2020 27.11.2020 CIP Ventnor Paddock Road, Shanklin Entire length Entire length 16.10.2020 27.11.2020 CIP Burnt House Lane, Newport Entire length Entire length 16.10.2020 27.11.2020 CIP Marlborough Road, Entire length Entire length 21.10.2020 23.10.2020 Barrier repairs -

Youngwoods Farm

YOUNGWOODS FARM Whitehouse Road, Porchfield, Isle of Wight, PO30 4LJ RURAL CONSULTANCY | SALES | LETTINGS | DESIGN & PLANNING YOUNGWOODS FARM Whitehouse Road, Porchfield, Isle of Wight, PO30 4LJ A beautiful six-bedroom Georgian Farmhouse complemented by a range of attractive farm buildings all with far reaching views to the Solent and Tennyson Down. Set in a secluded position within 84 acres of pastureland & woodland. Available as a whole or in two separate lots. Guide Price (Whole): £1,600,000 Lot 1 - (Farmhouse, Barns and 7.14 acres of Pastureland/Woodland): £1,155,000 Lot 2 - (Pastureland and Woodland 75.19 acres): £445,000 YOUNGWOODS FARMHOUSE Kitchen | Boot Room | Downstairs W/C | Larder | Office | Sitting Room | Study Master bedroom with en-suite | Second bedroom with en-suite | Family Bathroom Four further bedrooms, 3 double, 1 single | Gardens of around 1.5 acres In all approximately 3515 ft2 (275 m2) BUILDINGS Two Substantial stone barns | Hay Barn | Range of stone single storey barns Timber sheep sheds LAND A single block of 75.19 acres of high nature value pasture land and woodland (Lot 2) 7.14 acres of pastureland/woodland (Lot 1) In all approx. 83.83 acres (33.93 ha) For sale by private treaty Available as a whole or in two separate lots RURAL CONSULTANCY | SALES | LETTINGS | DESIGN & PLANNING YOUNGWOODS FARM Dating back to 1294 “Hengewode” has been a farm settlement for over 700 years with regenerations of the house into its current Georgian form. At the heart of Youngwoods is a characterful 6-bedroom farmhouse, an attractive range of traditional farm buildings (with potential for conversion) all set within pastureland/woodland of high nature conservation value extending to in total to 83.83 acres (33.93 ha). -

Island Roads Works Weekly Programme Update Week Commencing Monday 18Th May 2020

Service Provider Programme - Island Roads Works Weekly Programme Update Week Commencing Monday 18th May 2020 Carriageway Resurfacing Works Location Estimated Start Estimated Finish Traffic Management Details & Explanation Nunwell Farm Lane, Brading Road Closure - Day Works St Marys Improvement Scheme, Newport TBC Corve Lane, Chale Road Closure - Day Works Gladices Lane, Chale Road Closure - Day Works Elmsworth Lane, Porchfield Road Closure - Day Works Sun Hill, Cowes Road Closure - Day Works Moortown Lane, Calbourne Road Closure - Day Works Well Lane, Brading Road Closure - Day Works Circular Road, Seaview Road Closure - Day Works Lower Church Road, Gurnard For exact start & finish dates, please refer to Road Closure - Day Works Orchard Road, East Cowes Service Provider Programme - Resurfacing Road Closure - Day Works Oakwood Close, Ryde Road Closure - Day Works Yelfs Road, Ryde Road Closure - Day Works Fishbourne Lane, Wootton Road Closure - Day Works Rowborough Lane, Brading Road Closure - Night Works Grange Road, East Cowes Road Closure - Day Works East Cowes Road, Newport Road Closure - Day Works Garfield Road, Ryde Road Closure - Night Works Melville Sreet, Ryde Road Closure - Night Works Hillside, Newport Road Closure - Night Works Major Works Location Estimated Start Estimated Finish Traffic Management Details & Explanation Royal Exchange, Newport Mon 01/06/2020 Fri 19/06/2020 Road Closure / At all times Carriageway reconstruction Cadets Walk, East Cowes Mon 01/06/2020 Fri 06/06/2020 Road Closure / At all times Concrete bay repairs -

Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan ANNEX 4 TECHNICAL INFORMATION Prepared By: Isle of Wight Local Authority Emergency Management Version: 1.1 Island Resilience Forum 245 Version 1.0 Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan Date: March 2011 May 2010 BLANK ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Island Resilience Forum 246 Version 1.1 Multi-Agency Flood Response Plan March 2011 Not Protectively Marked Annex 4 – Technical Information Contents ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Annex 4 – Technical Information Page Number 245 Section 1 – Weather Forecasting and Warning • Met Office 249 • Public Weather Service (PWS) 249 • National Severe Weather Warning Service (NSWWS) 250 • Recipients of Met Office Weather Warnings 255 • Met Office Storm Tide Surge Forecasting Service 255 • Environment Monitoring & Response Centre (EMARC) 256 • Hazard Manager 256 Section 2 – Flood Forecasting • Flood Forecasting Centre 257 • Flood Forecasting Centre Warnings 257 • Recipients of Flood Forecasting Centre Warnings 263 Section 3 – Flood Warning • Environment Agency 265 • Environment Agency Warnings 266 • Recipients of Environment Agency Flood Warnings 269 Section 4 – Standard Terms and Definitions • Sources/Types of Flooding 271 • Affects of Flooding 272 • Tide 273 • Wind 276 • Waves 277 • Sea Defences 279 • Forecasting 280 Section 5 – Flood Risk Information Maps • Properties at Flood Risk 281 • Areas Susceptible to Surface Water Flooding