Promoting the Accuracy and Accountability of the Davis–Bacon Act

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Legislative and Congressional Districts

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 2011 Minnesota House and Senate Membership ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Rep. Dan Fabian-(R) A Rep. Steve Gottwalt-(R) A Rep. Duane Quam-(R) A Rep. Sarah Anderson-(R) A Rep. John Kriesel-(R) B Rep. Deb Kiel-(R) B Rep. King Banaian-(R) B Rep. Kim Norton-(DFL) B Rep. John Benson-(DFL) B Rep. Denny McNamara-(R) Sen. LeRoy A. Stumpf-(DFL) Sen. John Pederson-(R) Sen. David Senjem-(R) Sen. Terri Bonoff-(DFL) Sen. Katie Sieben-(DFL) ! 1 15 29 43 57 A Rep. Kent Eken-(DFL) A Rep. Sondra Erickson-(R) A Rep. Tina Liebling-(DFL) A Rep. Steve Simon-(DFL) A Rep. Joe Mullery-(DFL) B Rep. David Hancock-(R) B Rep. Mary Kiffmeyer-(R) B Rep. Mike Benson-(R) B Rep. Ryan Winkler-(DFL) B Rep. Bobby Joe Champion-(DFL) Sen. Rod Skoe-(DFL) Sen. Dave Brown-(R) Sen. Carla Nelson-(R) Sen. Ron Latz-(DFL) Sen. Linda Higgins-(DFL) 2 16 30 44 58 ! A Rep. Tom Anzelc-(DFL) A Rep. Kurt Daudt-(R) A Rep. Gene Pelowski Jr.-(DFL) A Rep. Sandra Peterson-(DFL) A Rep. Diane Loeffler-(DFL) B Rep. Carolyn McElfatrick-(R) B Rep. Bob Barrett-(R) B Rep. Gregory Davids-(R) B Rep. Lyndon Carlson-(DFL) B Rep. Phyllis Kahn-(DFL) ! ! ! Sen. Tom Saxhaug-(DFL) Sen. Sean Nienow-(R) Sen. Jeremy Miller-(R) Sen. Ann H. Rest-(DFL) Sen. Lawrence Pogemiller-(DFL) 2011 Legislati! ve and Congressional Districts 3 17 31 45 59 A Rep. John Persell-(DFL) A Rep. Ron Shimanski-(R) A Rep. Joyce Peppin-(R) A Rep. Michael Nelson-(DFL) A Rep. -

Congressional Scorecard 109Th Congress 2 0 0 5 - 2006

IRANIAN AMERICAN POLITICAL ACTION COMMITTEE Congressional Scorecard 109th Congress 2 0 0 5 - 2006 Please visit us on the web at www.iranianamericanpac.org About IAPAC IAPAC is a registered bipartisan political action committee that contributes to candidates for public office who are attuned to the domestic concerns of the Iranian American community. IAPAC focuses exclusively on domestic policy issues such as civil rights and immigration, and it encourages Americans of Iranian descent to actively participate in civic affairs. Mission • To support and promote the election of candidates for federal, state and local office, regardless of party affiliation, who are attuned to the domestic needs and issues of the Iranian American community • To support and promote Iranian American participation in civic affairs Issue Advocacy Civil Liberties: Balancing Civil Liberties and National Security in the Post-9/11 Era. Protecting our security and ensuring that the government does not infringe upon basic constitutional rights have long been important issues for civil libertarians and certain ethnic communities. IAPAC believes that our government must take the appropriate measures to protect our nation from further atrocities, but that it can do so without eliminating basic constitutional rights. Immigration: Immigration reform that is driven by proper national security concerns and remedies based on a fair and accurate appraisal of deficiencies in the immigration process, and not simply on national origin. Specifically, IAPAC advocates for a fair and measured execution of federal regulations governing the issuance of non-immigrant and immigrant visas for Iranian nationals. Congressional Scorecard The IAPAC 2005-2006 Congressional Scorecard rates members of Congress on votes and other positions taken in the House of Representatives and the Senate in the 109th Congress, which affect the domestic needs of the Iranian American community. -

Appendix G: Mailing List

Appendix G: Mailing List Appendix G / Mailing List 187 Appendix G: Mailing List The following is an initial list of government offices, private organizations, and individuals who will receive notice of the availablity of this CCP. We continue to add to this list and expect to mail several thousand notices or summary CCPs. Elected Officials Sen. Mark Dayton Sen. Norm Coleman Rep. Jim Ramstad Rep. John Kline Rep. Mark Kennedy Rep. Betty McCollum Rep. Martin Sabo Rep. Collin Peterson Rep. Gil Gutknecht Gov. Tim Pawlenty Local Government City of Bloomington City of Arden Hills City of Eden Prairie City of Eagan City of Burnsville City of Savage City of Shakopee City of Chanhassen City of Chaska City of Carver City of Jordon Hennepin County Dakota County Carver County Scott County Sibley County Le Sueur County Rice County Waseca County Steel County Blue Earth County Nicollet County Ramsey County Appendix G / Mailing List 189 Washington County Chisago County Hennepin County Park District Metropolitan Airports Commission Hennepin County Soil and Water Conservation District Dakota County Soil and Water Conservation District Carver County Soil and Water Conservation District Scott County Soil and Water Conservation District Sibley County Soil and Water Conservation District Le Sueur County Soil and Water Conservation District Rice County Soil and Water Conservation District Waseca County Soil and Water Conservation District Steel County Soil and Water Conservation District Blue Earth County Soil and Water Conservation District Nicollet County Soil -

CHLA 2017 Annual Report

Children’s Hospital Los Angeles Annual Report 2017 About Us The mission of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is to create hope and build healthier futures. Founded in 1901, CHLA is the top-ranked children’s hospital in California and among the top 10 in the nation, according to the prestigious U.S. News & World Report Honor Roll of children’s hospitals for 2017-18. The hospital is home to The Saban Research Institute and is one of the few freestanding pediatric hospitals where scientific inquiry is combined with clinical care devoted exclusively to children. Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is a premier teaching hospital and has been affiliated with the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California since 1932. Table of Contents 2 4 6 8 A Message From the Year in Review Patient Care: Education: President and CEO ‘Unprecedented’ The Next Generation 10 12 14 16 Research: Legislative Action: Innovation: The Jimmy Figures of Speech Protecting the The CHLA Kimmel Effect Vulnerable Health Network 18 20 21 81 Donors Transforming Children’s Miracle CHLA Honor Roll Financial Summary Care: The Steven & Network Hospitals of Donors Alexandra Cohen Honor Roll of Friends Foundation 82 83 84 85 Statistical Report Community Board of Trustees Hospital Leadership Benefit Impact Annual Report 2017 | 1 This year, we continued to shine. 2 | A Message From the President and CEO A Message From the President and CEO Every year at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles is by turning attention to the hospital’s patients, and characterized by extraordinary enthusiasm directed leveraging our skills in the arena of national advocacy. -

NRCC: MN-07 “Vegas, Baby”

NRCC: MN-07 “Vegas, Baby” Script Documentation AUDIO: Taxpayers pay for Colin Peterson’s Since 1991, Peterson Has Been Reimbursed At personal, private airplane when he’s in Minnesota. Least $280,000 For Plane Mileage. (Statement of Disbursements of House, Chief Administrative Officer, U.S. House of Representatives) (Receipts and Expenditures: Report of the Clerk of TEXT: Collin Peterson the House, U.S. House of Representatives) Taxpayers pay for Peterson’s private plane Statement of Disbursements of House AUDIO: But do you know where else he’s going? Peterson Went Las Vegas On Trip Sponsored By The Safari Club International From March AUDIO: That’s right. Vegas, Baby. Vegas. 22, 2002 To March 25, 2002 Costing, $1,614. (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) Peterson Went Las Vegas On Trip Sponsored By The American Federation Of Musicians From June 23, 2001 To June 25, 2001, Costing $919. (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) Peterson Went Las Vegas On Trip Sponsored By The Safari Club International From January 11, 2001 To January 14, 2001, Costing $918.33. (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) AUDIO: Colin Peterson took 36 junkets. Vacation- Throughout His Time In Congress, Peterson like trips, paid for by special interest groups. Has Taken At Least 36 Privately Funded Trip Worth $57,942 (Collin Peterson, Legistorm, Accessed 3/17/14) TEXT: 36 Junkets paid for by special interest groups See backup below Legistorm AUDIO: In Washington, Peterson took $6 million in Collin Peterson Took $6.7 Million In Campaign campaign money from lobbyists and special Money From Special Interest Group PACs interests. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E561 HON

March 25, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E561 During this same time, Callahan won rave Muskegon Norsemen were ranked third in the during a time of national emergency. This reviews for his skills as a legislator, with The state after the regular season. SMCC was waiver authority addresses the need to assist Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post unranked most of the year before finally mak- students who are being called up to active praising on him as ‘‘an unlikely champion.’’ He ing No. 10 in the last week. duty or active service. later became the chairman of the influential During the regular season, the girls were This bill is specific in its intent—to ensure House Appropriations Subcommittee on En- known for their astonishing comebacks. In the that as a result of a war, military contingency ergy and Water Development in the 107th State final, the girls were down 9–0 in the first operation or a national emergency: Affected Congress. game before they embarked on their amazing borrowers of Federal student assistance are Mr. Speaker, Sonny Callahan was a dedi- comeback that will go down in state volleyball not in a worse financial position; administrative cated public servant and an honorable Ala- history. The team finished their remarkable requirements on affected individuals are mini- bamian. Let us take this time to reflect on his season with a 40–10–4 record. mized without affecting the integrity of the pro- work in this historic chamber and thank him Mr. Speaker, I would like to ask all my col- grams; current year income of affected individ- for his dedication to his country and the peo- leagues to rise and join me in congratulating uals may be used to determine need for pur- ple of Alabama. -

Extensions of Remarks E1343 HON. GEORGE MILLER HON. JOHN

July 17, 1998 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E1343 and native violet, the Illinois state flower. Those sailors were neither traitors nor de- THE FOOD SAFETY ENFORCEMENT Bringing this native vegetation back to an en- serters, as some have suggested. They ENHANCEMENT ACT OF 1998 vironment that is now urban, has not been an sought the same post-traumatic leave as was easy task. For example, Mr. Kline has had to allowed their white officer counterpartsÐleave HON. JOHN ELIAS BALDACCI replace the garden's urban soil. Mr. Kline has they were denied because of their race. They OF MAINE sought remediation of the unquestionably haz- upheld his strong determination to complete IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES his vision for the garden, diligently researching ardous conditions involved in loading the ships native plants and remaining patient with the which undoubtedly contributed to the events Friday, July 17, 1998 garden. Mr. Kline is growing non-native flow- leading to the explosion, including the dan- Mr. BALDACCI. Mr. Speaker today I, along ers such as tulips to provide some color to the gerous competition among loading crews pro- with a host of my colleagues, am introducing garden, while he is waiting for the soil to be- voked by officers. the Food Safety Enforcement Enhancement come rich enough for a complete native gar- Now, along with 40 or our colleagues in the Act of 1998. I believe that one of this govern- den. House of Representatives, I am seeking the ment's fundamental responsibilities is ensuring Mr. Kline's hard work and dedication to the personal intervention of President Clinton to that Americans have the safest food possible. -

Congressional Directory MINNESOTA

144 Congressional Directory MINNESOTA MN; professional: high school teacher; military: Command Sergeant Major, Minnesota’s 1st / 34th Division of the Army National Guard, 1981–2005; awards: 2002 Minnesota Ethics in Education award winner, 2003 Mankato Teacher of the Year, and the 2003 Minnesota Teacher of Excellence; married: Gwen Whipple Walz, 1994; children: Hope and Gus; committees: Agri- culture; Armed Services; Veterans’ Affairs; elected to the 110th Congress on November 7, 2006; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings http://www.walz.house.gov 1034 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ........................................... (202) 225–2472 Chief of Staff.—Josh Syrjamaki. FAX: 225–3433 Legislative Director.—Timothy Bertocci. Scheduler.—Denise Fleming. 5271⁄2 South Front Street, Mankato, MN 56001 ........................................................................ (507) 388–2149 12021⁄2 Seventh Street, NW., Suite 211, Rochester, MN 55901 .............................................. (507) 388–2149 Counties: BLUE EARTH COUNTY.CITIES: Amboy, Eagle Lake, Garden City, Good Thunder, Lake Crystal, Madison Lake, Mankato, Mapleton, Pemberton, St. Clair, Vernon Center. BROWN COUNTY.CITIES: Comfrey, Hanska, New Ulm, Sleepy Eye, Springfield. COTTONWOOD COUNTY.CITIES: Mountain Lake, Storedon, Westbrook. DODGE COUNTY.CITIES: Clare- mont, Dodge Center, Hayfield, Kasson, Mantorville, West Concord, Windom. FARIBAULT COUNTY.CITIES: Blue Earth, Bricelyn, Delavan, Easton, Elmore, Frost, Huntley, Kiester, Minnesota Lake, Walters, Wells, Winnebago. FILLMORE COUNTY.CITIES: Canton, Chatfield, Fountain, Harmony, Lanesboro, Mabel, Ostrander, Peterson, Preston, Rushford, Spring Valley, Whalan, Wykoff. FREEBORN COUNTY.CITIES: Albert Lea, Alden, Clarks Grove, Conger, Emmons, Freeborn, Geneva, Glenville, Hartland, Hayward, Hollandale, London, Manchester, Myrtle, Oakland, Twin Lakes. HOUSTON COUNTY.CITIES: Brownsville, Caledonia, Eitzen, Hokah, Houston, La Crescent, Spring Grove. JACKSON COUNTY.CITIES: Heron, Jackson, Lake Field. -

Advocatevolume 20, Number 5 September/October 2006 the Most Partisan Time of the Year Permanent Repeal of the Estate Tax Falls Victim to Congressional Battle

ADVOCATEVolume 20, Number 5 September/October 2006 The Most Partisan Time of the Year Permanent repeal of the estate tax falls victim to congressional battle By Jody Milanese Government Affairs Manager s the 109th Congress concludes— with only a possible lame-duck Asession remaining—it is unlikely Senate Majority Leader William Frist (R-Tenn.) will bring the “trifecta” bill back to the Senate floor. H.R. 5970 combines an estate tax cut, minimum wage hike and a package of popular tax policy extensions. The bill fell four votes short in August. Frist switched his vote to no dur- ing the Aug. 3 consideration of the Estate Tax and Extension of Tax Relief Act of 2006, which reserved his right COURTESY ISTOCKPHOTO as Senate leader to bring the legisla- The estate tax—and other parts of the current tax system—forces business owners to tion back to the floor. Despite Frist’s pay exorbitant amounts of money to the government and complete myriad forms. recent statement that “everything is any Democrats who voted against that, as of now, there is no intension on the table” for consideration prior the measure would switch their of separating elements of the trifecta to the November mid-term elections, position in an election year. package before a lame-duck session. many aides are doubtful the bill can Frist has given a task force of Since failing in the Senate in be altered enough to garner three four senators—Finance Chairman August, there has been wide debate more supporters. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), Budget over the best course of action to take Senate Minority Leader Harry Chairman Judd Gregg (R-N.H.), in achieving this top Republican pri- Reid (D-Nev.) has pushed hard to Policy Chairman Jon Kyl (R-Ariz.) ority. -

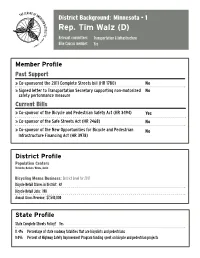

Tim Walz (D) Rep

District Background: Minnesota - 1 Rep. Tim Walz (D) Relevant committees: Transportation & Infrastructure Bike Caucus member: Yes Member Profile Past Support » Co-sponsored the 2011 Complete Streets bill (HR 1780) No » Signed letter to Transportation Secretary supporting non-motorized No safety performance measure Current Bills » Co-sponsor of the Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Act (HR 3494) Yes » Co-sponsor of the Safe Streets Act (HR 2468) No » Co-sponsor of the New Opportunities for Bicycle and Pedestrian No Infrastructure Financing Act (HR 3978) District Profile Population Centers Rochester, Mankato, Winona, Austin Bicycling Means Business: District Level for 2012 Bicycle Retail Stores in District: 42 Bicycle Retail Jobs: 198 Annual Gross Revenue: $7,540,000 State Profile State Complete Streets Policy? Yes 11.4% Percentage of state roadway fatalities that are bicyclists and pedestrians 0.0% Percent of Highway Safety Improvement Program funding spent on bicycle and pedestrian projects District Background: Minnesota - 2 Rep. John Kline (R) Relevant committees: None Bike Caucus member: No Member Profile Past Support » Co-sponsored the 2011 Complete Streets bill (HR 1780) No » Signed letter to Transportation Secretary supporting non-motorized No safety performance measure Current Bills » Co-sponsor of the Bicycle and Pedestrian Safety Act (HR 3494) No » Co-sponsor of the Safe Streets Act (HR 2468) No » Co-sponsor of the New Opportunities for Bicycle and Pedestrian No Infrastructure Financing Act (HR 3978) District Profile Population Centers Eagan, Burnsville, Apple Valley, Lakeville Bicycling Means Business: District Level for 2012 Bicycle Retail Stores in District: 43 Bicycle Retail Jobs: 206 Annual Gross Revenue: $13,010,000 State Profile State Complete Streets Policy? Yes 11.4% Percentage of state roadway fatalities that are bicyclists and pedestrians 0.0% Percent of Highway Safety Improvement Program funding spent on bicycle and pedestrian projects District Background: Minnesota - 3 Rep. -

The Honorable Collin C. Peterson

A Ceremony Unveiling the Portrait of THE HONORABLE COLLIN C. PETERSON Tuesday, April 5, 2011 1300 Longworth Building Washington, D.C. VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:24 May 17, 2011 Jkt 041481 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6748 Sfmt 6748 I:\DOCS\PETERS~1\65894.TXT BRIAN CONGRESS.#13 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:24 May 17, 2011 Jkt 041481 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6748 Sfmt 6748 I:\DOCS\PETERS~1\65894.TXT BRIAN COMMITTEE PRINT A Ceremony Unveiling the Portrait of THE HONORABLE COLLIN C. PETERSON A Representative in Congress from the State of Minnesota January 3, 1991–Present Elected to the 102nd Congress Chairman of the Committee on Agriculture One Hundred Tenth through One Hundred Eleventh Congresses PROCEEDINGS before the COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE U.S. House of Representatives April 5, 2011 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2011 65–894 PDF VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:24 May 17, 2011 Jkt 041481 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6748 Sfmt 6748 I:\DOCS\PETERS~1\65894.TXT BRIAN CONGRESS.#13 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:24 May 17, 2011 Jkt 041481 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6748 Sfmt 6748 I:\DOCS\PETERS~1\65894.TXT BRIAN A Ceremony Unveiling the Portrait of THE HONORABLE COLLIN C. PETERSON COMMITTEE ON AGRICULTURE U.S. House of Representatives Tuesday, April 5, 2011 [ III ] VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:24 May 17, 2011 Jkt 041481 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 6748 Sfmt 6748 I:\DOCS\PETERS~1\65894.TXT BRIAN VerDate 0ct 09 2002 15:24 May 17, 2011 Jkt 041481 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 6748 Sfmt 6748 I:\DOCS\PETERS~1\65894.TXT BRIAN v The Honorable Collin C. -

The Politics of Trauma

THE POLITI OF TRAUMA CS The Rhodes Cook Letter September 2005 The Rhodes Cook Letter SEPTEMBER 2005 / VOL. 6, NO. 5 (ISSN 1552-8189) Contents The Politics of Trauma . 3 Chart & Graph: Rep. Strength in Congress since the Election of Bush I . 3 Chart: Presidents and Their Parties in the 6-Year Midterm Elections . 4 Chart: Bush Coattail Pull in 2004 . 5 Chart: Targets of Opportunity in 2006? . 6 Chart: Bush Coattails in Historical Terms . 7 Chart & Map: Senators up in ‘06: How They Ran in 2000. 8 Chart & Map: The Ohio 2nd Special Election: A Harbinger for ‘06? . 9 Chart: The GOP’s Evolving Congressional Base . 10 Wrapping Up 2004: Party Registration . 11 Chart & Map: Dems. Reps., Others: Where They Stood by State in Nov. ‘04 . 11 Chart & Map : The Prescience of Party Registration Totals in 2004. 12 Chart & Map : Registration by State from Election to Election, 2000-04 . 13 In the News . 16 Chart: The Changing Composition of the 109th Congress. 16 Chart: What’s up in 2006. 16 The Rhodes Cook Letter is published by Rhodes Cook. Web: tion for six issues is $99. Make check payable to “The Rhodes rhodescook.com. E-mail: [email protected]. Design by Cook Letter” and send it, along with your e-mail address, to Landslide Design, Rockville, MD. “The Rhodes Cook Letter” P.O. Box 574, Annandale, VA. 22003. See the last page of this is published on a bimonthly basis. An individual subscrip- newsletter for a subscription form. All contents are copyrighted ©2005 Rhodes Cook. Use of the material is welcome with attribution, although the author retains full copyright over the material contained herein.