Marine Ecology Progress Series 562:193

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sizing Ocean Giants: Patterns of Intraspecific Size Variation in Marine Megafauna

Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna Craig R. McClain1,2 , Meghan A. Balk3, Mark C. Benfield4, Trevor A. Branch5, Catherine Chen2, James Cosgrove6, Alistair D.M. Dove7, Lindsay C. Gaskins2, Rebecca R. Helm8, Frederick G. Hochberg9, Frank B. Lee2, Andrea Marshall10, Steven E. McMurray11, Caroline Schanche2, Shane N. Stone2 and Andrew D. Thaler12 1 National Evolutionary Synthesis Center, Durham, NC, USA 2 Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA 3 Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA 4 Department of Oceanography and Coastal Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA 5 School of Aquatic & Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA 6 Natural History Section, Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, BC, Canada 7 Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta, GA, USA 8 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA 9 Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, Santa Barbara, CA, USA 10 Marine Megafauna Foundation, Truckee, CA, USA 11 Department of Biology and Marine Biology, University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wilmington, NC, USA 12 Blackbeard Biologic: Science and Environmental Advisors, Vallejo, CA, USA ABSTRACT What are the greatest sizes that the largest marine megafauna obtain? This is a simple question with a diYcult and complex answer. Many of the largest-sized species occur in the world’s oceans. For many of these, rarity, remoteness, and quite simply the logistics of measuring these giants has made obtaining accurate size measurements diYcult. Inaccurate reports of maximum sizes run rampant through the scientific Submitted 3 October 2014 literature and popular media. -

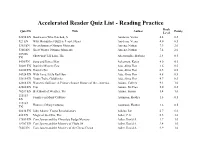

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

Winter 2016 in This Issue Photo: Alex Constan Alex Photo: from the President in These Cold Winter Months, I Often Pause to Enjoy the Aquarium’S Tropical Exhibits

It’s time to live blue™ The Phoenix Islands Protected Area Meet Myrtle, the queen of the Giant Ocean Tank New England’s undersea treasure Members’ Magazine Volume 49, Number 1 Winter 2016 In This Issue Photo: Alex Constan Alex Photo: From the President In these cold winter months, I often pause to enjoy the Aquarium’s tropical exhibits. The colors and abundance of life consis- tently delight me and also remind me of how vulnerable these systems are. In this issue of blue, we’ll journey to one of the most remote tropical coral reef systems on the planet. In September, a team of scientists from the Aquarium, the Woods Hole Oceano- graphic Institution and other collaborators visited the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA), one of the largest marine protected areas in the world. They collected data that will help to manage the reserve and— in the midst of one of the most intense El Niños ever—observed the effects of climate change, without the complicating Cool Animals Future Ocean Protectors factors that affect most coral reef systems. 2 6 Myrtle the green sea turtle Nature is so weird. Did you know? Closer to home, our conservation team has been raising awareness of two extraordinary gems off our own coasts: 3 Research Briefs 8 Global Explorers Cashes Ledge, an underwater mountain A potential pregnancy test for Researchers return to the range that supports New England’s long-dead whales, and the growing Phoenix Islands Protected Area largest and deepest kelp forest, and the problem of big fish in home tanks Coral Canyons and Seamounts, home to 10 Members’ Notes rare deep sea corals and invertebrates. -

Winter 2014 on the Cover: Northern Fur Seals Photo: K

It’s time to live blue™ A female fur seal is born at the Aquarium Aquarium scientists search for new ways to protect right whales Going solar Members’ Magazine Volume 47, Number 1 Winter 2014 On the cover: Northern fur seals Photo: K. Ellenbogen blue is a quarterly magazine exclusively for members of the New England Aquarium produced and published by New England Aquarium, Central Wharf, Boston, MA, 02110. Publishing office Aquarium researchers are experimenting with ways to keep right whales like this one from getting entangled in fishing located at 177 Milk St., line. In this magazine all photographs of right whales in U.S. waters were taken under NMFS/NOAA permit under the Boston, MA, 02109. blue authority of the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the U.S. Endangered Species Act. and all materials within are property of the New England Aquarium. Reproduction of any In This Issue @neaq.org materials is possible only through written Dive into a sea of resources online. www.neaq.org permission. Cool Animal: Kitovi 2 Meet our newest Northern fur seal. The website is full of conservation information, © blue 2014 animal facts and details that will help you plan your next trip to the Aquarium. Editor live blue™: Solar Panels and Ann Cortissoz 4 Citizen Scientists Throughout this issue of blue, look for Designer Cathy LeBlanc this icon to point out items that you Future Ocean Protectors: can explore further on our website. Contributors 6 Emily Bauernfeind Using Colors to Save Right Whales Jeff Ives Scientists search for new methods to help Plan Your Visit Scott Kraus these endangered giants. -

EDUCATOR GUIDE EDUCATOR GUIDE Humpback Fun Facts

Macgillivray Freeman’s presented by pacific life EDUCATOR GUIDE EDUCATOR GUIDE Humpback fun Facts WEIGHT At birth: 1 ton LENGTH Adult: 25 - 50 tons Up to 55 feet, with females larger DIET than males; newborns are Krill, about 15 feet long small fish APPEARANCE LIFESPAN Gray or black, with white markings 50 to 90 years on their undersides THREATS Entanglement in fishing gear, ship strikes, habitat impacts 4 EDUCATOR GUIDE The Humpback Whales Educator Guide, created by MacGillivray Freeman Films Educational Foundation in partnership with MacGillivray Freeman Films and Orange County Community Foundation, is appropriate for all intermediate grades (3 to 8) and most useful when used as a companion to the film, but also valuable as a resource on its own. Teachers are strongly encouraged to adapt activities included in this guide to meet the specific needs of the grades they teach and their students. Activities developed for this guide support Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), Ocean Literacy Principles, National Geography Standards and Common Core Language Arts (see page 27 for a standards alignment chart). An extraordinary journey into the mysterious world of one of nature’s most awe-inspiring marine mammals, Humpback Whales takes audiences to Alaska, Hawaii and the remote islands of Tonga for an immersive look at how these whales communicate, sing, feed, play and take care of their young. Captured for the first time with IMAX® 3D cameras, and found in every ocean on earth, humpbacks were nearly driven to extinction 50 years ago, but today are making a steady recovery. Join a team of researchers as they unlock the secrets of the humpback and find out what makes humpbacks the most acrobatic of all whales, why they sing their haunting songs, and why these 55-foot, 50-ton animals migrate up to 10,000 miles round-trip every year. -

Ocean Giants: Giant Lives 4Th Annual Coastal Discovery Stewardship

4th Coastal Discovery Jan 13 - & Stewardship Feb 28 2017 Annual Celebration FREE movie at Hearst Castle Theater Ocean Giants: Giant Lives Discover the intimate details of the great whales. Every Saturday from January 14 – February 25 at 6pm Starts at 6:45 2/18 and 2/25 The California Central Coast is a spectacular place to watch marine mammals from shore. Visit www.TheWhaleTrail.org to find six viewing locations in Coastal San Luis Obispo County. 40 Must-Do Celebration Activities and Events Visit www.Highway1DiscoveryRoute.com/Stewardship-Travel for dates and times. • 3rd Annual BlendFest on the Coast Wine Event • Central Coast Aquarium Shark Feeding and Tour • Avila Beach Bird Sanctuary & Wildlife Day • Elephant Seal Docent Led Walks • Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Natural History Center • Piedres Blancas Light Station Historical Tours VERYROU CO TE. IS CO 1D M Y A W H G I For Lodging Specials and Details go to: H Highway1DiscoveryRoute.com/Stewardship-Travel Wildlife Viewing and Stewardship Tips Visit Highway1DiscoveryRoute.com/Stewardship-Travel Be outside during dawn, dusk, and incoming tides. Birds, fish, and mammals are active during these times. Look for churning water surfaces, diving birds, shiny dolphin backs, seals and otters in bays and on open water. Listen for songbirds singing in bushes and trees, especially during spring and early summer. Be calm and stay awhile. Adopt an unhurried, ‘vacation’ state of mind. A state of relaxed alertness is the best way to see wildlife. Blend in. Animals react to movement. Sit quietly next to a bush or tree and practice the ‘art of invisibility.’ Keep it steady. -

Kiszka Et Al Report V2 Rrr Tc

Intended for IOTC-WPEB 2017 use only – Do not cite without consent from the author Cetacean bycatch in the western Indian Ocean: a review of available information on coastal gillnet, tuna purse seine and pelagic longline fisheries Jeremy J. Kiszka1, Per Berggren2, Gill Braulik3, Tim Collins4, Gianna Minton5 & Randall Reeves6 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, North Miami, USA 2 School of Natural & Environmental Sciences, Newcastle University, UK 3 Sea Mammal Research Unit, University of St Andrews, United Kingdom. 4 Megaptera Marine Conservation, Wassenaar, the Netherlands 5 Wildlife Conservation Society, Ocean Giants Program, Bronx, New York, USA 6 Okapi Wildlife Associates, Hudson, Quebec, Canada. Email: [email protected] Abstract Bycatch is the most significant and immediate threat to cetacean populations at the global scale. Here we review available information on cetacean bycatch in industrial and small-scale (mostly artisanal) fisheries in the western Indian Ocean (WIO). In coastal waters of the WIO region, the impact of bycatch has not been quantified in small-scale fisheries, except in bottom-set gillnets and driftnets targeting large pelagic fish (including tuna) off Zanzibar. Based on bycatch data from observer programs and estimated abundance of coastal dolphins, the bycatch off the south coast of Zanzibar was found to be unsustainable. Elsewhere in the region, other species are also bycaught, including coastal, oceanic and migratory species such as humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), mostly in bottom-set and drift gillnets. In open-ocean fisheries, bycatch in pelagic longlines has been recorded but seems to be rare. Species affected are mostly medium-sized delphinids (Globicephala macrorhynchus, Grampus griseus, Pseudorca crassidens) involved in depredation (on either bait or catch). -

WHALES of the ANTARCTIC PENINSULA Science and Conservation for the 21St Century CONTENTS

THIS REPORT HAS BEEN PRODUCED IN COLLABORATION WITH REPORT ANTARCTICA 2018 WHALES OF THE ANTARCTIC PENINSULA Science and Conservation for the 21st Century CONTENTS Infographic: Whales of the Antarctic Peninsula 4 1. PROTECTING OCEAN GIANTS UNDER INCREASING PRESSURES 6 2. WHALES OF THE ANTARCTIC PENINSULA 8 Species found in the Antarctic Peninsula are still recovering from commercial whaling 10 Infographic: Humpback whale migration occurs over multiple international and national jurisdictions 12 Whales face several risks in the region and during migrations 15 Authors: Dr Ari Friedlaender (UC Santa Cruz), Michelle Modest (UC Baleen whales use the Antarctic Peninsula to feed on krill Santa Cruz) and Chris Johnson (WWF Antarctic programme). – the keystone species of the Antarctic food chain 16 Contributors: Infographic: The Western Antarctic Peninsula is critical Dr David Johnston (Duke University), Dr Jennifer Jackson feeding habitat for humpback whales 20 (British Antarctic Survey) and Dr Sarah Davie (WWF-UK). Whales play a critical role in Southern Ocean ecosystems 22 Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Rod Downie (WWF-UK), Dr Reinier Hille Ris Lambers (WWF-NL), Rick Leck (WWF-Aus), 3. NEW SCIENCE IS CHANGING OUR UNDERSTANDING OF WHALES 24 Duke University Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab, California Ocean Alliance and One Ocean Expeditions. Technology is providing scientists and policymakers with data to better understand, monitor and conserve Antarctic whales 26 Graphic Design: Candy Robertson Copyediting: Melanie Scaife Satellite and suction-cup tags uncover whale foraging areas and behaviour 28 Front cover photo: © Michael S. Nolan / Robert Harding Picture Library / National Geographic Creative / WWF Long-Term Ecological Research – Palmer Station, Antarctica 29 Photos taken under research permits include: Dr Ari Drones uncovering a new view from above 30 Friedlaender NMFS 14809, ACA 2016-024 / 2017-034, UCSC IACUC friea1706, and ACUP 4943. -

Whales: Giants of the Deep March 19, 2016 Through September 5, 2016

Whales: Giants of the Deep March 19, 2016 through September 5, 2016 Contents Welcome ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Volunteer Logistics ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Reporting for Service ................................................................................................................................ 1 Scheduling ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Logistics for Interpretative Cart ................................................................................................................ 1 Representing the Museum ....................................................................................................................... 2 Logging Your Volunteer Hours .................................................................................................................. 2 Adding Yourself to the Schedule ............................................................................................................... 3 Introduction to Cetaceans ............................................................................................................................ 3 Classification of Cetaceans ......................................................................... Error! Bookmark -

Chapter 2 of Cetaceans and Ships; Or, the Moorings of Our Being

Chapter 2 Of Cetaceans and Ships; or, The Moorings of Our Being “L’imagination . se lassera plutôt de concevoir que la nature de fournir.” (Te imagination runs dry sooner than nature does.) —Pascal, Pensées Is the Sea a Medium? To understand media, we should start not on land but at sea. Te sea has long seemed the place par excellence where history ends and the wild be- gins: the abyss, a vast deep and dark mystery, unrecorded, unknown, un- mapped. Melville called the sea “Inviolate Nature primeval.” It has long been a profoundly unnatural environment for humans in both life and in thought. Seventy- one percent of the earth’s surface has been a sub- lime, uncanny place without limits and beyond understanding, the ulti- mate wasteland. Te ocean was once roiling with dragons, Leviathans, and pirates— a merciless mix of fate, wind, and weather that imperiled anyone brave or foolish enough to risk their life on ship. It is still a very dangerous place, a kind of planetary waste dump and graveyard for many forms of life, including hapless immigrants. Only recently have humans dipped much below its surface, with depth exploration historically having been limited to the shoreline. Both Babylonian and Hebrew ori- gin myths describe creation as the conquest of chaotic uncreated waters (tiamat, tehom). Te Book of Revelation, at the opposite end of the Bible from Genesis, seals this conquest by announcing a new heaven and earth 53 54 CHAPTER TWO in which the sea is no more, abolished as if in a fnal act of spite (Revela- tions 21:1). -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Documentary Or Nonfiction Special American Murder: The Family Next Door Using raw, firsthand footage, to examine the disappearance of Shanann Watts and her children, and the terrible events that followed. The Battle Never Ends Millions of American veterans made a sacrifice to protect our country’s democracy. Honoring the 100-year anniversary of the Disabled American Veterans, a group which has fought to protect the rights and improve the lives of those who pay the price of freedom every day. The Bee Gees: How Can You Mend A Broken Heart Chronicling the triumphs and hurdles of The Bee Gees. Brothers Barry, Maurice, and Robin Gibb, found early fame writing over 1,000 songs with twenty No. 1 hits transcending through over five decades. Featuring never-before-seen archival footage of recording sessions, home videos, concert performances, and a multitude of interviews. Belushi Belushi unveils the brilliant life of a comedic legend. Family and friends share memories of a John Belushi few knew, including Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner, Chevy Chase, Penny Marshall, Lorne Michaels and Harold Ramis. Biggie: I Got A Story To Tell Featuring rare footage and in-depth interviews, this documentary celebrates the life of The Notorious B.I.G. on his journey from hustler to rap king. BLACKPINK: Light Up The Sky Korean girl band BLACKPINK tell their story — and detail the journey of the dreams and trials behind their meteoric rise. Booker T (Biography) Re-live the journey of Booker T, who transformed himself from teenage criminal serving time in prison to one of the most beloved WWE superstars. -

Minutes Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium

MINUTES LOUISIANA UNIVERSITIES MARINE CONSORTIUM EXECUTIVE BOARD Wyndham Garden New Orleans Airport Hotel, Marigny Room, 6401 Veterans Memorial Blvd., Metairie, LA April 25, 2016, 3:00 PM I. Call to Order (Dr. Laura Levy) Dr. Laura Levy, Chair, LUMCON Executive Board, called the meeting of the Executive Board for the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium to order on April 25, 2016 in the Marigny Room of the Wyndham Garden New Orleans Airport Hotel, Metairie, at 3:00 p.m. II. Roll Call (Debbie Cenac) LUMCON Executive Board members present for the meeting: * Dr. Kalliat T. Valsaraj, Louisiana State University and A&M College Vice Chancellor for Research and Development *Dr. Neal Weaver, Nicholls State University Vice President, University Advancement *Dr. Ramesh Kolluru, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Vice President for Research *Dr. Laura Levy, Tulane University Vice President for Research *Dr. Eric Pani, University of Louisiana at Monroe Vice President for Academic Affairs Dr. Christopher D’Elia, Louisiana State University and A&M College Dean, School of the Coast & Environment Dr. John Doucet, Nicholls State University Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Uma Subramanian, Deputy Commissioner for Legal and External Affairs Ex-officio for Board of Regents *Denotes voting members of the LUMCON Executive Board. Guests in attendance: LUMCON Staff: Debbie Cenac, later joined by Heidi Boudreaux and Dr. Nancy Rabalais Dr. Levy determined that 5 of 8 voting members of the LUMCON Executive Board constituted a quorum, and Dr. Levy called the meeting to order. III. Approval of Prior Minutes Dr. Levy called for the approval of the prior minutes.