The Eucharistic Sermons of Ronald Knox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

MARCH 12, 2017 JMJ Dear Parishioners, This Second Week of Lent We Will Again Look at Why We Are Praying the Mass the Way We Are Here at Saint Mary’S

SECOND S UNDAY OF LENT MARCH 12, 2017 JMJ Dear Parishioners, This second week of Lent we will again look at why we are praying the Mass the way we are here at Saint Mary’s. Mass celebrated ver- sus populum has the danger of putting the gathered community and the priest himself, instead of the Eucharist, as the center of worship. At its worst, a cult of personality can be built up around whichever priest “presider” is funniest and most effusive. Like a comedian playing to an audience, the laughter of the congregation at his quirks and eccentricities can even build up a certain clerical narcissism within himself. The celebration of Mass versus populum places the priest front and center, with all of his eccentricities on display. Even priests such as myself who make every effort to celebrate Mass versus populum with a staidness and sobriety easily succumb to its inherent deficiencies. In fact, celebrating the Mass versus populum is just as distracting to the congregation as it is to the priest. While celebrating Mass ad orientem does not immediately cure every moment of distraction, it provides a concrete step in reorienting the focus of the Mass. It allows for a certain amount of anonymity for the priest, restoring the importance of what he does rather than who he is. By returning the focus to the Eucharist, ad orientem worship also restores a sense of the sacred to the Mass. Recalling Aristotle’s definition of a slave as a “living tool,” Msgr. Ronald Knox encouraged this imagery when thinking of the priest: “[T]hat is what the priest is, a living tool of Jesus Christ. -

Is Feeneyism Catholic? / François Laisney

I S F That there is only one true Church, the one, Holy, Catholic, EENEYISM Apostolic, and Roman Church, outside of which no one can be saved, has always been taught by the Catholic Church. This dogma, however, has been under attack in recent times. Already last century, the Popes had to repeatedly rebuke the liberal Catholics for their tendency to dilute this The Catholic dogma, “reducing it to a meaningless formula.” But in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, the same dogma was C Meaning of misrepresented on the opposite side by Fr. Feeney ATHOLIC and his followers, changing “outside the Church there is The Dogma, no salvation” into “without water baptism there is absolutely no salvation,” thereby denying doctrines which had been “Outside the positively and unanimously taught by the Church, that is, Baptism of Blood and Baptism of Desire. ? Catholic Church IS FEENEYISM REV. FR. FRANÇOIS LAISNEY There Is No CATHOLIC? Salvation” What is at stake?—Fidelity to the unchangeable Catholic Faith, to the Tradition of the Church. We must neither deviate on the left nor on the right. The teaching Church must “religiously guard and faithfully explain the deposit of Faith that was handed down through the Apostles,…this apostolic doctrine that all the Fathers held, and the holy orthodox Doctors reverenced and followed” (Vatican I); all members of the Church must receive that same doctrine, without picking and choosing what they will believe. We may not deny a point of doctrine that belongs to the IS deposit of Faith—though not yet defined—under the pretext that it has been distorted by the Liberals. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The churches and the bomb = an analysis of recent church statements from Roman Catholics, Anglican, Lutherans and Quakers concerning nuclear weapons Holtam, Nicholas How to cite: Holtam, Nicholas (1988) The churches and the bomb = an analysis of recent church statements from Roman Catholics, Anglican, Lutherans and Quakers concerning nuclear weapons, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6423/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Churches and the Bomb = An analysis of recent Church statements from Roman Catholics, Anglican, Lutherans and Quakers concerning nuclear weapons. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Nicholas Holtam M„Ae Thesis Submitted to the University of Durham November 1988. -

UCLA Historical Journal

UCLA UCLA Historical Journal Title Protestant "Righteous Indignation": The Roosevelt Vatican Appointment of 1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0bv0c83x Journal UCLA Historical Journal, 17(0) ISSN 0276-864X Author Settje, David Publication Date 1997 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 124 UCLA Historical Journal Protestant "Righteous Indignation": The Roosevelt Vatican Appointment of 1940 David Settje C t . ranklin D. Roosevelt's 1940 appointment of a personal representative / * to the Vatican outraged most Protestant churches. Indeed, an / accounting of the Protestant protests regarding the Holy See appointment reveals several aspects of American religious life at that time. As the United States moved closer to becoming a religiously plurahstic society and shed its Protestant hegemony, mainline Protestant churches sought to maintain leverage by denouncing any ties to the Vatican. Efforts to avert this papal affiliation also stemmed from traditional American anti-Cathohcism. Therefore, the attempt to preserve Protestant influence with anti-Catholic rhetoric against a Vatican envoy demonstrates how mainline churches want- ed to sway governmental pohcy, even in the area of foreign affairs. Protestant churches asserted that they were defending the principle of the separation of church and state. But an inspection of their protests against the Vatican appointment illustrates that they were also concerned about how such repre- sentation would affect their place in U.S. society and proves that they still dis- trusted Catholicism. In short, although they cloaked their arguments in the guise of defending the separation of church and state, the Vatican appoint- ment became a forum in which Protestant denominations displayed their anxiety about the development of religious pluralism in America, voiced tra- ditional anti-Catholicism, and ultimately influenced diplomatic policy. -

Solidarity and Mediation in the French Stream Of

SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Timothy R. Gabrielli Dayton, Ohio December 2014 SOLIDARITY AND MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. APPROVED BY: _________________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor _________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Anthony J. Godzieba, Ph.D. Outside Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Vincent J. Miller, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Faculty Reader _________________________________________ Daniel S. Thompson, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Timothy R. Gabrielli All rights reserved 2014 iii ABSTRACT SOLIDARITY MEDIATION IN THE FRENCH STREAM OF MYSTICAL BODY OF CHRIST THEOLOGY Name: Gabrielli, Timothy R. University of Dayton Advisor: William L. Portier, Ph.D. In its analysis of mystical body of Christ theology in the twentieth century, this dissertation identifies three major streams of mystical body theology operative in the early part of the century: the Roman, the German-Romantic, and the French-Social- Liturgical. Delineating these three streams of mystical body theology sheds light on the diversity of scholarly positions concerning the heritage of mystical body theology, on its mid twentieth-century recession, as well as on Pope Pius XII’s 1943 encyclical, Mystici Corporis Christi, which enshrined “mystical body of Christ” in Catholic magisterial teaching. Further, it links the work of Virgil Michel and Louis-Marie Chauvet, two scholars remote from each other on several fronts, in the long, winding French stream. -

Preserving Christian Publications, Inc. RADITIONAL ATHOLIC OOKS T C B Specializing in Used and Out-Of-Print Titles Catalog 173 August 2015

Preserving Christian Publications, Inc. TRADITIONAL CATHOLIC BOOKS Specializing in Used and Out-of-Print Titles Catalog 173 August 2015 PCP, Inc. is a tax-exempt not-for-profit corporation devoted to the preservation of our Catholic heritage. All charitable contributions toward the used-book and publishing activities of PCP (not including payments for book purchases) are tax-deductible. Cardinal Merry del Val on the Authority of the Pope “The Truth of Papal Claims, by Raphael Cardinal Merry del Val, which Preserving Christian Publications has recently reprinted . is a worthy edition of an important Catholic work.” – Raymond Leo Cardinal Burke “Hence Dr. Oxenham may learn, that by Infallibility we do not mean ‘impeccability’ or sinlessness in the person of S. Peter or of his successors, who are accountable to God for their own consciences and their own lives like every other human being; ... we do not mean that the Roman Pontiff receives special revelations from heaven, or that by a revelation of the Holy Spirit he may invent or teach new doctrines not contained in the deposit of Faith, though, when occasion offers, and especially in times of conflict, he may define a point which all have not clearly recognized in that Faith, or which some may be striving to put out of view. Nor do we mean that every utterance that proceeds from the Pope’s mouth, or from the Pope’s pen, is infallible because it is his. Great as our filial duty of reverence is towards whatever he may say, great as our duty of obedience must be to the guidance of the Chief Shepherd, we do not hold that every word of his is infallible, or that he must always be right. -

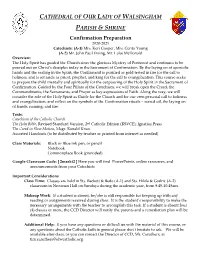

Confirmation Preparation 2020-2021 Catechists: (A-1) Mrs

CATHEDRAL OF OUR LADY OF WALSINGHAM PARISH & SHRINE Confirmation Preparation 2020-2021 Catechists: (A-1) Mrs. Keri Cooper, Mrs. Cerita Young (A-2) Mr. John Paul Ewing, Mr. Luke McDonald Overview: The Holy Spirit has guided the Church since the glorious Mystery of Pentecost and continues to be poured out on Christ’s disciples today in the Sacrament of Confirmation. By the laying on of apostolic hands and the sealing in the Spirit, the Confirmand is purified as gold tested in fire for the call to holiness, and is set aside as priest, prophet, and king for the call to evangelization. This course seeks to prepare the child mentally and spiritually for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the Sacrament of Confirmation. Guided by the Four Pillars of the Catechism, we will break open the Creed, the Commandments, the Sacraments, and Prayer as key expressions of Faith. Along the way, we will consider the role of the Holy Spirit as Guide for the Church and for our own personal call to holiness and evangelization, and reflect on the symbols of the Confirmation rituals – sacred oil, the laying on of hands, naming, and fire. Texts: Catechism of the Catholic Church The Holy Bible, Revised Standard Version, 2nd Catholic Edition (RSVCE), Ignatius Press The Creed in Slow Motion, Msgr. Ronald Knox Assorted Handouts (to be distributed by teacher or printed from internet as needed) Class Materials: Black or Blue ink pen, or pencil Notebook Commonplace Book (provided) Google Classroom Code: [ 2mzeki2 ] Here you will find PowerPoints, online resources, and announcements from your Catechists Important Considerations Class Time: Classes are held in Sts. -

19630628.Pdf

THE CRITERION, JUNE ?8, I963 PAGE THRES - SupremeCourt decision Help t'or aging - Cotugo Ar home ::31:r""::-T,.ll:..^l: l.l:: ll^".111",.^11.1groups ha\,e brought:.:l'J...111"..,:.'.'li*i?ll' aboul Ihtr "thr.otrgh improvement conlol'- cnces ancl an cxchangc ol in{or'- " nration. Abroad I LONDON-]'he luling l,abor' I'arty in Australia rvill not butlgc ft'ortt its opposition to g.rveln- nrent aid to Catholic antl othcr' privatc schools, thc ptlty's lcatlcr. has rleclaletl hcrc. Arthur' (.lal- well insisted that sialc glants lo non.public schools are not. pos- sible undel the plesent. Cornrnon. wcalth eonstitution. Cnln'el[. rvho is a Catholic, said thal. clenton- stlations by Catholic pa|cnts agaittst the govet'nmcnt's policl'. Office of Education here, de- f \ rvhich inclrrtlctl ntass tt'attsfcls ol scribed lhe school siluation ar , I "dismal." stttdents fronr Catholic to public The strike involves I I "no schools, rvoukl have lusting 37,500 leachers and rffecls | ^ - ^ | c[[cct''intlrosc[rooldisettssit.rtrs'morelhanami||ionpupi|s.i}fl-l o\%u,j*tAMOUNT TO BETREPAIoBE REPAIO ovERlOVER I I sAN'ro DotttN(;o. Dotttitticurt ; l-1 I YOU Fro |lr,lrrrlrlit,-|l|irslltrt.a..;i:i;l';;i#|eohi-ow|ro-o".|romoo,|z|mos.|!BORROW 36m 30 moo. 2l mos. li.:;',lllill:,:i':lt:i';',llli.'li:|.llll|isll!llJr/ohffil$ 600 29.00 000 40,00 48.3i1 lilll;\,:]l:'T;ll.'i]l.ll,.:lli:1"iil,jliitT'rUlH"fA1500 $51.66 60.00 72.50 rclij.tion u,ilI cvcntuaIlv disappenr'. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

Current Theology Christian Co-Operation

CURRENT THEOLOGY CHRISTIAN CO-OPERATION One of the most striking characteristics of the religious scene today is the assertion of a growing will among Christians to work together for a more human and Christian world-order, in the face of concerted, organized, and implacable forces that threaten to destroy the possibility of it. Christian co operation among men of different creeds in the interests of social reconstruc tion is a fact. The fact, of course, is simply massive in England. In the United States it has nowhere near the same proportions, but it is likely that it may assume them. The fact posits an essentialJy theological problem, that is being increas ingly felt as such by theologians. One of them writes: "The Catholic heart warms to such high and noble endeavor; the Catholic theologian knows it involves association with heretics and scents danger and difficulty. This attitude of the theologian, if left vague and confused, can cause misunder standing: to the layman, full of the possibilities of fruitful co--0peration, it can seem retrograde, unhelpful, suspicious of his zeal and enthusiasm in a good cause."1 It is, consequently, not surprising that a layman writes: "One of the next tasks in theology is, it seems to me, to dear up the prin ciples of that co-operation of men of different creeds which is required by the common good of temporal society." 2 Moreover, it has been pointed out by the Editor of Blackfriars that the task is not at all simple: "The whole question ... demands careful and pre cise theological expression to show how far colJaboration is possible.