Forcing Herbaceous Perennials to Flower After Storage Outdoors Under a Thermoblanket

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rain Gardens and Bioswales

PERENNIALS Lysimachia clethroides, Gooseneck TREES AND SHRUBS PLANTING & Loosestrife Mc, Mt !*Achillea millefolium, Yarrow D, Mc Lysimachia nummularia, Creeping Jenny !*Acer circinatum, Vine Maple D, Mc, Mt MAINTENANCE Aconitum camichaelii, Monkshood Mc, Mt Mc, Mt !Acer rubrum, Red Maple D, Mc, Mt, W *Adiantum sp., Maidenhair Fern Mt, W Lysimachia punctata Mc, Mt *Alnus rhombifolia, rubra, Alder Mt, W SITE AND SOIL PREPARATION: Alcea officinalis, Marsh Mallow Mt, W Matteuccia struthiopteris, Ostrich Fern Mc, Betula nigra, River Birch Mt, W Use the calculator at OSU’s website (see Amsonia tabernae-montana, Blue Star Mt Mt, W *Betula papyrifera, Paper Birch Mc, Mt, W references) to determine the size and depth !*Aquilegia formosa, Red Columbine Mc, *Mimulus guttatus, Monkey Flower Mt, W Clethra sp., Summersweet Mc, Mt, W of your rain garden. Amend the soil so the Mt, D Monarda didyma, Bee Balm Mc, Mt !*Cornus sericea, Red-Twig Dogwood D, mix is roughly 50% native soil, 30% !*Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, Bearberry D, Mc Myosotis palustris, Forget-Me-Not Mc, Mt Mc, Mt, W compost, and 20% pumice. !*Aruncus dioicus, Goat’s Beard Mc, Mt Osmunda sp., Cinnamon Fern Mt, W Fraxinus americana, White Ash Mc, Mt, W Asclepias incarnata, Butterfly Weed Mt, W !Penstemon digitalis Mc, Mt Magnolia virginiana, Sweetbay Mc, Mt, W MULCHING: Two kinds of mulch are *Aster sp. D, Mc, Mt !*Penstemon globosus Mc, Mt !*Mahonia sp., Oregon Grape D, Mc important in a rain garden. A mulch of pea Astilbe cvs. Mc, Mt !*Penstemon (Oregon natives) D, Mc !*Malus, Crabapple D, Mc gravel or river rocks at the point where Boltonia asteroides, False Starwort Mt, W Physostegia virginiana, Obedient Plant Mc, !*Philadelphus lewisii, Mock Orange D, Mc, water enters will help prevent erosion; this !*Camassia D, Mc Mt Mt mulch should be thick enough that no soil Campanula, Bellflower D, Mc, Mt !*Polystichum munitum, Sword Fern Mc, Mt !*Physocarpus capitatus, Pacific Ninebark D, shows through. -

Plants for Damp Or Wet Areas

Editor’s note: This information sheet comes from the Clemson University Cooperative Extension, Home and Garden Division, Prepared by Karen Russ, HGIC Horticulture Specialist, Clemson University. Among the many information sources, this one appeared to be the most thorough and user-friendly list. Note that all plants listed may not be hardy in Western New York, or for your particular site. Check for Hardiness Zone 5 or lower, and for the sunlight requirements and other plant needs before purching these plants for your wet sites. S.J. Cunningham Plants for Damp or Wet Areas Plants marked with an * are more tolerant of very wet or periodically flooded conditions. When selecting plants using this list, remember that a number of factors determine the suitability of a plant for a particular location. In addition to adaptability to moisture, also consider light requirements, soil type, hardiness and heat tolerance, and other factors. Trees (Botanical Name - Common Name) Tall Deciduous Trees (50 feet or more in height at maturity) • *Acer rubrum - Red Maple • *Quercus nigra - Water Oak • *Carya illinoinensis - Pecan • Quercus palustris - Pin Oak • Catalpa species - Catalpa • *Quercus bicolor - Swamp White Oak • *Fraxinus pennsylvanica - Green Ash • *Quercus phellos - Willow Oak • *Liquidambar styraciflua - Sweet Gum • *Salix species - Willows • Metasequoia glyptostroboides - Dawn Redwood • *Taxodium ascendens - Pond Cypress • *Platanus occidentalis - Sycamore • *Taxodium distichum - Bald Cypress Medium Deciduous Trees (30 to 50 feet in height) -

Perennials for Specific Sites and Uses, HYG-1242-98

Perennials for Specific Sites and Uses, HYG-1242-98 http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/1000/1242.html Ohio State University Extension Fact Sheet Horticulture and Crop Science 2001 Fyffe Court, Columbus, OH 43210 Perennials for Specific Sites and Uses HYG-1242-98 Jane C. Martin Extension Agent, Horticulture Franklin County Gardeners often seek that "perfect" herbaceous (non-woody) perennial plant to fill a special location or need in the landscape. Below are listed some perennial plants useful for special purposes based on central Ohio growing conditions and experiences. Your experience with the plant may vary somewhat. Of course, this list is not all inclusive, but includes plants that should perform well for you; use it as a guide and then plan some further research on your own. Sometimes many plants in a genus will fit the category given and are listed as "Hosta spp.," for instance. Do more research to narrow your selection within the genus. Occasionally, a specific cultivar is listed (in single quotes), indicating that the particular plant is the best choice within the species. The Latin name and a common name are given for most listings. Plants for Sunny, Dry Areas Achillea spp.-Achillea or Yarrow Anthemis tinctoria-Golden Marguerite Arabis caucasica-Rock Cress Armeria maritima-Common or Sea Thrift Artemisia spp.-Artemesia Asclepias tuberosa-Butterfly Weed Catananche caerulea-Cupid's Dart Coreopsis spp.-Coreopsis Echinops ritro-Small Globe Thistle Euphorbia spp.-Spurge Gaillardia spp.-Blanket Flower Helianthus x multiflorus-Perennial Sunflower 1 of 5 9/15/2006 8:01 AM Perennials for Specific Sites and Uses, HYG-1242-98 http://ohioline.osu.edu/hyg-fact/1000/1242.html Hemerocallis hybrids-Daylily Lavandula angustifolia-English Lavender Liatris spp.-Gayfeather Malva alcea-Hollyhock Mallow Oenothera spp.-Sundrops Opuntia humifusa-Prickly Pear Cactus Perovskia atriplicifolia-Russian Sage Polygonum cuspidatum var. -

Recommended Xeriscape Plant List for Salina

Recommended Xeriscape Plant List for Salina Large Deciduous Shrubs (over 8’) Autumn Olive Elaeagnus umbellata Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Common Buckthorn Rhamnus cathartica Elderberry Sambucus canadensis Lilac Syringa vulgaris Ninebark Physocarpus opulifolius Rough-leafed Dogwood Cornus drummondii Sandhill Plum Prunus angustifolia Siberian Pea Shrub Caragana arborescen Staghorn Sumac Rhus typhina Wahoo Enonymus atropurpureus Western Sandcherry Prunus besseyi Wild Plum Prunus americana Medium Deciduous Shrubs (4’ to 8’) Butterfly Bush Buddleia davidii Dwarf Ninebark Physocarpus opulifolius nanus Flowering Quince Chaenomeles speciosa Fragrant Sumac Rhus aromatica Serviceberry Amelanchier spp. Shining Sumac Rhus copallina Three Leaf Sumac Rhus trilobata Small Deciduous Shrubs (under 4’) Alpine Currant Ribes alpinum Bluemist Spirea Caryopteris clandonensis Coralberry, Buckbrush Symphoricarpos orbiculatus False Indigo Amorpha fruticosa Golden Currant Ribes odoratum Golden St. Johnswort Hypericum frondosum Gooseberry Ribes missouriense Gro-Low Fragrant Sumac Rhus aromatica. ‘GroLow’ Landscape Roses Rosa many varieties Leadplant Amorpha canescens New Jersey Tea Ceanothus ovatus Prairie Rose Rosa suffulta Pygmy Pea Shrub Caragana pygmaea Russian Sage Perovskia atriplicifolia Large Evergreen Shrubs Eastern Redcedar Juniperus virginiana Mugho Pine Pinus mugo Medium Evergreen Shrubs Junipers Juniperus various species Page 1 of 3 Small Evergreen Shrubs Compact Mugho Pine Pinus mugo various cultivars Juniper Juniperus various species Soapweed Yucca -

New York Non-Native Plant Invasiveness Ranking Form

NEW YORK NON -NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Lysimachia clethroides Duby USDA Plants Code LYCL2 Common names: Goose-neck loosestrife Native distribution: Eastern Asia Date assessed: April 11, 2008; October 12, 2008 Assessors: Steve Glenn, Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: 10/22/2008 Form version date: 10 July 2009 New York Invasiveness Rank: Not Assessable Distribution and Invasiveness Rank (Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form ) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Not Assessed Not Assessable 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 ( ) 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 ( ) 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 ( ) 4 Difficulty of control 10 ( ) Outcome score 100 ( )b a † Relative maximum score § New York Invasiveness Rank Not Assessable * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. §Very High >80.00; High 70.00−80.00; Moderate 50.00−69.99; Low 40.00−49.99; Insignificant <40.00 Not Assessable: not persistent in NY, or not found outside of cultivation. -

Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an Updated Checklist

Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32306 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.7.e32306 Taxonomic Paper Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an updated checklist Hongfeng Wang‡§, Xueyun Dong , Yi Liu|,¶, Keping Ma | ‡ School of Forestry, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China § School of Food Engineering Harbin University, Harbin, China | State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China ¶ University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Corresponding author: Hongfeng Wang ([email protected]) Academic editor: Daniele Cicuzza Received: 10 Dec 2018 | Accepted: 03 Mar 2019 | Published: 27 Mar 2019 Citation: Wang H, Dong X, Liu Y, Ma K (2019) Tracheophyte of Xiao Hinggan Ling in China: an updated checklist. Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e32306. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e32306 Abstract Background This paper presents an updated list of tracheophytes of Xiao Hinggan Ling. The list includes 124 families, 503 genera and 1640 species (Containing subspecific units), of which 569 species (Containing subspecific units), 56 genera and 6 families represent first published records for Xiao Hinggan Ling. The aim of the present study is to document an updated checklist by reviewing the existing literature, browsing the website of National Specimen Information Infrastructure and additional data obtained in our research over the past ten years. This paper presents an updated list of tracheophytes of Xiao Hinggan Ling. The list includes 124 families, 503 genera and 1640 species (Containing subspecific units), of which 569 species (Containing subspecific units), 56 genera and 6 families represent first published records for Xiao Hinggan Ling. The aim of the present study is to document an updated checklist by reviewing the existing literature, browsing the website of National Specimen Information Infrastructure and additional data obtained in our research over the past ten years. -

Groundcovers—Nature's Living

The Seed A Publication of the Nebraska Statewide Arbore- Groundcovers—Nature’s Living Inside: Groundcovers for Sun & By Bob Henrickson incredible variety of groundcover Shade Too often, groundcovers are offerings—woody not considered when new landscape or herbaceous; Groundcover Prairie Grasses plantings are installed. Traditionally, the limbing, clumping or soil surface of new planting beds that running; evergreen or Woody Groundcovers incorporate trees, shrubs and herbaceous deciduous—in all kinds perennials is covered with a 2-3” layer of colors, textures and Establishing Groundcovers of organic mulch. The organic mulch fragrances, leaves an helps to conserve moisture, control array of possibilities for weeds and give the landscape a uniform, use as living mulch. finished look. However, it usually takes Mulch rings around a number of years before the plants trees are usually kept mature, prompting a yearly top-dressing to a minimum size to of mulch to keep the open areas covered. reduce maintenance This yearly addition of mulch can be upkeep. Under-planting relatively expensive and excessive mulch trees within the mulch Groundcovers can greatly reduce the need for weed- can build up on the soil. It can also be a zone is a good way to lot of work to mulch use groundcovers, and a good way to between plants. The dense carpet of expand the mulch bed around the tree. shrubbery or growing along a mowed leaves, intertwining stems and abundant By planting around trees, the trunks will edge. roots of living mulch can function in “Bare earth bothers me not be injured by being scraped with a Try planting a combination of many of the same ways as traditional lawn mower. -

Download Article

Available Online at http://www.journalajst.com ASIAN JOURNAL OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Asian Journal of Science and Technology Vol. 4, Issue, 12, pp. 02 4-027, December, 2012 ISSN: 0976-3376 RESEARCH ARTICLE MICROPROPAGATION OF LYSIMACHIA LAXA BAUDO *Sanjoy Gupta, S. Kaliamoorthy, 1Jayashankar Das, A. A. Mao and 2Soneswar Sarma *Botanical Survey of India, Eastern Regional Center, Lower New Colony, Laitumkhrah, Shillong – 793003, Meghalaya, India 1Plant Bioresources Division, Regional Centre of IBSD, Ganktok-737102, Sikkim, India 2 Department of Biotechnology, Gauhati University, Guwahati-781014, Assam, India Received 24th September, 2012; Received in Revised from; 28th October, 2012; Accepted 19th November, 2012; Published online 17th December, 2012 ABSTRACT An in vitro regeneration protocol was developed for Lysimachia laxa Baudo. Maximum number of shoot (9.10±0.32) was induced by culturing nodal explants in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with 17.76 µM benzyladenine (BA) and 5.37 µM α – naphthalene acetic acid (NAA). Elongated shoots were best rooted, with 100% rooting efficiency, in MS medium containing 2.85 µM indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). Among the two explants (nodal and shoot tips) used, nodal explants were found to be the best option for in vitro regeneration of Lysimachia laxa. Rooted plantlets thus developed were hardened in 2 months time by growing in root trainers containing potting mixture of a 1:1 mix of garden soil and leaf mould. The established plants were then transferred to earthen pots and subsequently transferred to field condition. Key words: Apical shoot tips, Lysimachia laxa Baudo., micropropagation, Murashige and Skoog medium, nodal segments INTRODUCTION nature is poor due to low seed germination percentage. -

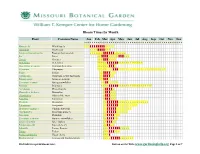

Bloom Times by Month

Bloom Times by Month Plant Common Name Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Hamamelis Witch hazels - - - X X X X X X X X - - - - - Galanthus Snowcrops - - - - X X X X - - - Lonicera fragrantissima Fragrant honeysuckle - - - - - - - X X X X X X - - - - - - Iris Irises - - X X X X - - - - - X X X - - - Crocus Crocuses - - - X X X - - - - Helleborus Hellebores - - - - - X X X X X X - - - - - - - - - - - - - Hyacinthus orientalis Common hyacinths - - - - - - X X X - Viburnum Viburnums - - - - - - - - X X X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Scilla Scillas - - X X X X - - - Cornus mas Cornelian cherry dogwoods - - X X X X - - Prunus mume Japanese apricots - - X X X - Leucojum vernum Spring snowflakes - - X X - - - - - Primula Primroses - - - - X X X X X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Corylopsis Winter hazels - X X X X - Magnolia x loebneri Magnolias - X X X - - - Chionodoxa Glory of the snow - X X X - - - Forsythia Forsythias - X X X - - - Magnolia Magnolias - - X X X X X X - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Pulmonaria Lungworts - - X X X X X X - - - - - - - - - - Mertensia virginica Virginia bluebells - - X X X X X - - - - - - - - Chaenomeles Flowering quinces - - X X X X X - - - - - - Narcissus Daffodils - - X X X X - - - Leucojum aestivum Summer snowflakes - - X X X X - - Lindera benzoin Spice bushes - - X X X - - Prunus sargentii Sargent cherry - - X X - - Pulsatilla Pasque flowers - - - X X X X X X - - - -

Volatiles in the Lysimachia Clethroides Duby by Head Space Solid Phase Microextraction Coupled with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS)

African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology Vol. 6(33), pp. 2484-2487, 5 September, 2012 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPP DOI: 10.5897/AJPP12.713 ISSN 1996-0816 © 2012 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Volatiles in the Lysimachia clethroides Duby by head space solid phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS) Jin-Feng Wei1,2,3, Zhen-hua Yin2 and Fu-De Shang1* 1College of Life Science, Henan University, Kaifeng 475004, China. 2Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, Henan University, Kaifeng 475004, China. 3Minsheng College, Henan University, Kaifeng 475004, China. Accepted 13 August, 2012 We studied for the first time, the volatile compounds in the Lysimachia clethroide Duby by using head space solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The results showed that 14 compounds were identified from the stem of L. clethroides, 13 compounds were identified from the leaves, and 16 compounds from the flowers. 8 compounds were mutual components, accounting for 92.99, 94.59 and 90.32% of the identified components in stem, leaves and flowers, respectively. Limonene was the main compound in the three parts, and the contents were up to 52.59, 54.57 and 44.98%, respectively. These showed that the volatiles had not much difference in the three parts; maybe the three parts have the same medicinal effect, and could provide certain theoretical basis for further development and utilization. Key words: Lysimachia clethroides Duby, solid phase microextraction, volatiles. INTRODUCTION Lysimachia clethroides Duby, belonging to the study was undertaken. This paper reports the Primulaceae family, is found in mild region of northeast components in the essential oil of L. -

Studies on the Chromosome Numbers in Higher Plants III* the Mode of Cell Division in PMC the Plants Described Below All Show

1939 205 Studies on the Chromosome Numbers in Higher Plants III* By T. Sugiura Osaka Higher School, Osaka Received January 27, 1939 Materials Materials used here were 42 species belonging to 22 families, raised from seeds. Some of them were sent from the chief botanical gardens in Europe, to the authorities of which the writer wishes to express his best thanks. The technique used in this work has been referred to in previous papers. The Mode of Cell Division in PMC The plants described below all show the furrowing process in the mode of the partition wall formation of the pollen mother cells (cf. Sugiura 1936b). Numbers of Chromosomes Compositae: Cosmos sulphureus, C. diversifolius. The numbers of chromosomes formerly found in Coreopsidinae were in Bidens 12, 24, in Coreopsis 12, and in Dahlia 16, but none in Cosmos. The writer formerly counted 24 somatic chromosomes in C. bipinnatus (1931). Now he has also counted 12 meiotic chromo somes in each of the above two species. The diversifolius species has somewhat larger meiotic chromo somes than those of the sulphureus at the same stage, although the outer appearance of the former was much smaller. As there is no secondary pairing of chromosomes to be seen in the meiotic division in these species, the basic number of chromosomes in Cosmos is probably 12. Campanulaceae (Lobelioideae): Lobelia Cliffortiana, L. inflata, L. Richardsonii, L. tenuior. The reported chromosome numbers in the genus Lobelia are shown in the Table 1. * The studies were made under the subsidy from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Scientific Research. -

When to Divide Perennials Herbaceous Perennials Are Commonly • Butterfly Weed (Asclepias Tuberosa)—A Taproot Makes Divided for Three Reasons: to Division Difficult

When to Divide Perennials Herbaceous perennials are commonly • Butterfly Weed (Asclepias tuberosa)—A taproot makes divided for three reasons: to division difficult. However, butterfly weed is easily control size, to rejuvenate propagated by seeds. plants, and to propagate a • Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum × morifolium)—Divide prized perennial. Vigorous mums every 2 or 3 years in spring. perennials may grow so rapidly that they crowd • Columbine (Aquilegia species)—Many species and out neighboring plants in the varieties are short-lived. Division is difficult, carefully flower bed. Other perennials divide in late summer. decline in vigor if not • Coral Bells (Heuchera species)—Divide in spring or late divided at the appropriate summer/early fall. time. One of the easiest ways to • Coreopsis (Coreopsis species)—Divide in spring or late propagate a prized perennial is to divide summer/early fall. the plant into two or more smaller plants. • Cornflower (Centaurea species)—Requires division every The best time to divide perennials varies with the different 2 or 3 years. Divide in spring. plant species. The appropriate times to divide widely • Daylily (Hemerocallis species)—Divide in spring or late grown perennials are listed below. summer/early fall. • Aster (Aster species)—Divide every 2 or 3 years • Delphinium (Delphinium species)—Usually short-lived, in spring. division is seldom necessary. • Astilbe (Astilbe species)—Divide every 3 or 4 years • False Indigo (Baptisia australis)—Division is difficult in spring. because of its long taproot. Plants can be started • Baby’s Breath (Gypsophila paniculata)—Division from seeds. is difficult, carefully divide in spring or late • Gooseneck Loosestrife (Lysimachia clethroides)—Plants summer/early fall.