Understanding and Managing Organizational Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Market for Financial Advice: an Audit Study

The Market for Financial Advice: An Audit Study Sendhil Mullainathan (Harvard University) Markus Nöth (University of Hamburg) Antoinette Schoar (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) April, 2011 A growing literature shows that households are prone to behavioral biases in choosing portfolios. Yet a large market for advice exists which can potentially insulate households from these biases. Advisers may efficiently mitigate these biases, especially given the competition between them. But advisers’ self interest – and individuals’ insufficiently correcting for it – may also lead to them giving faulty advice. We use an audit study methodology with four treatments to document the quality of the advice in the retail market. The results suggest that the advice market, if anything, likely exaggerates existing biases. Advisers encourage chasing returns, push for actively managed funds, and even actively push them on auditors who begin with a well‐diversified low fee portfolio. Keywords: financial advice, audit study JEL: D14, G11 We thank John Campbell and Michael Haliassos, and seminar participants at Columbia, York, MIT Sloan, SAVE Deidesheim, and ESSFM Gerzensee 2010 for their helpful comments. 1. Introduction A growing body of lab – and to a lesser extent field – evidence argues that individual investors make poor financial decisions. Drawing on research in psychology, this evidence argues that consumers’ beliefs and decision processes lead them astray. They chase trends, are overconfident, use heuristics and generally fall prey to biases that lead them to choose in ways at odds with basic portfolio theory. For example, the median household rebalances its retirement portfolio zero times (Samuelson and Zeckhauser, 1988), whereas in traditional portfolio theory rebalancing would be optimal in response to aging and the realization of uncertain returns. -

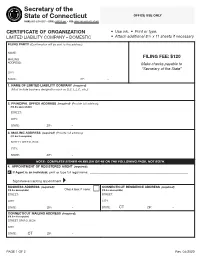

Certificate of Organization (LLC

Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB: www.concord-sots.ct.gov CERTIFICATE OF ORGANIZATION • Use ink. • Print or type. LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY – DOMESTIC • Attach additional 8 ½ x 11 sheets if necessary. FILING PARTY (Confirmation will be sent to this address): NAME: FILING FEE: $120 MAILING ADDRESS: Make checks payable to “Secretary of the State” CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 1. NAME OF LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (required) (Must include business designation such as LLC, L.L.C., etc.): 2. PRINCIPAL OFFICE ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 3. MAILING ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – NOTE: COMPLETE EITHER 4A BELOW OR 4B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE, NOT BOTH. 4. APPOINTMENT OF REGISTERED AGENT (required): A. If Agent is an individual, print or type full legal name: _______________________________________________________________ Signature accepting appointment ▸ ____________________________________________________________________________________ BUSINESS ADDRESS (required): CONNECTICUT RESIDENCE ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box unacceptable) Check box if none: (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: STREET: CITY: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – STATE: CT ZIP: – CONNECTICUT MAILING ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: CT ZIP: – PAGE 1 OF 2 Rev. 04/2020 Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] -

Organizational Behavior Management in Health Care: Applications for Large-Scale Improvements in Patient Safety

Organizational Behavior Management in Health Care: Applications for Large-Scale Improvements in Patient Safety Thomas R. Cunningham, MS, and E. Scott Geller, PhD Abstract Medical errors continue to be a major public health issue. This paper attempts to bridge a possible disconnect between behavioral science and the management of medical care. Epidemiologic data on patient safety and a sampling of current efforts aimed at patient safety improvement are provided to inform relevant applications of organizational behavior management (OBM). The basic principles of OBM are presented, along with recent innovations in the field that are relevant to improving patient safety. Safety-related applications of behavior- based interventions from both the behavioral and medical literature are critically reviewed. Potential OBM targets in health care settings are integrated within a framework of those OBM techniques with the greatest possibility of improving patient safety on a large scale. Introduction Organizational behavior management (OBM) focuses on what people do, analyzes why they do it, and then applies an evidence-based intervention strategy to improve what people do. The relevance of OBM to improving health care is obvious. While poorly designed systems contribute to most medical errors, OBM provides a practical approach for addressing a critical component of every imperfect health care system—behavior. Behavior is influenced by the system in which it occurs, yet it can be treated as a unique contributor to many medical errors, and certain changes in behavior can prevent medical error. This paper reviews the principles and procedures of OBM as they relate to reducing medical error and improving health care. -

Exploring the Conceptual Expansion Within the Field of Organizational Behavior: Organizational Climate and Organizational Culture

Exploring the conceptual expansion within the field of organizational behavior: Organizational climate and organizational culture. Willem Verbeke, Marco Volgering, and Marco Hessels Erasmus University Rotterdam Abstract Developments within social and exact sciences take place because scientists engage in scientific practices that allow them to further expand and refine the scientific concepts within their scientific disciplines. There is disagreement among scientists as to what the essential practices are that allow scientific concepts within a scientific discipline to expand and evolve. One group looks at conceptual expansion as something that is being constrained by rational practices. Another group however suggests that conceptual expansion proceeds along the lines of ‘everything goes.’The goal of this paper is to test whether scientific concepts expand in a rational way within the field of organizational behavior. We will use organizational climate and culture as examples. The essence of this study consists of two core concepts: one within organizational climate and one within organizational culture. It appears that several conceptual variations are added around these core concepts. The variations are constrained by rational scientific practices. In other terms, there is evidence that the field of organizational behavior develops rationally. 1. Introduction In every scientific discipline scholars come to ask what the researchers in their field have been doing, what the focus of research should be and/or where their research field is or should be heading to. These kind of questions are also being asked in the field of organizational behavior by scholars like Schneider (1985), Dunnette (1991) and O'Reilly (1991). From a theoretical point of view, these scholars question what and how scientific concepts--like emotions, organizational environment, performance etc.--could be used in order to answer the more fundamental question within their discipline: “i.e. -

Organizational Culture Model

A MODEL of ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE By Don Arendt – Dec. 2008 In discussions on the subjects of system safety and safety management, we hear a lot about “safety culture,” but less is said about how these concepts relate to things we can observe, test, and manage. The model in the diagram below can be used to illustrate components of the system, psychological elements of the people in the system and their individual and collective behaviors in terms of system performance. This model is based on work started by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1970’s. It’s also featured in E. Scott Geller’s text, The Psychology of Safety Handbook. Bandura called the interaction between these elements “reciprocal determinism.” We don’t need to know that but it basically means that the elements in the system can cause each other. One element can affect the others or be affected by the others. System and Environment The first element we should consider is the system/environment element. This is where the processes of the SMS “live.” This is also the most tangible of the elements and the one that can be most directly affected by management actions. The organization’s policy, organizational structure, accountability frameworks, procedures, controls, facilities, equipment, and software that make up the workplace conditions under which employees work all reside in this element. Elements of the operational environment such as markets, industry standards, legal and regulatory frameworks, and business relations such as contracts and alliances also affect the make up part of the system’s environment. These elements together form the vital underpinnings of this thing we call “culture.” Psychology The next element, the psychological element, concerns how the people in the organization think and feel about various aspects of organizational performance, including safety. -

Customer Relationship Management, Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact on Customer Loyalty

Customer Relationship Management, Customer Satisfaction and Its Impact on Customer Loyalty Sulaiman, Said Musnadi Faculty of Economic and Business, University of Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia Keywords: Customer Relationship Management, Satisfaction, Customer Loyalty. Abstract: This study aims to determine the effect of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) on Customer Satisfaction and its impact on Customer Loyalty of Islamic Bank in Aceh’s Province. The study population is all customers in in the Islamic Bank. This study uses convinience random sampling with a sample size of 250 respondents. The analytical method used is structural equation modeling (SEM). The results showed that the Customer Relationship Management significantly influences both on satisfaction and its customer loyalty. Furthermore, satisfaction also affects its customer loyalty. Customer satisfaction plays a role as partially mediator between the influences of Customer Relationship Management on its Customer Loyalty. The implications of this research, the management of Islamic Bank needs to improve its Customer Relationship Management program that can increase its customer loyalty. 1 INTRODUCTION small number of studies on customer loyalty in the bank, as a result of understanding about the loyalty 1.1 Background and satisfaction of Islamic bank’s customers is still confusing, and there is a very limited clarification The phenomenon underlying this study is the low about Customer Relationship Management (CRM) as a good influence on customer satisfaction and its -

An Exploration of Organizational Buying Behavior in the Public Sector

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Marketing and Supply Chain Marketing & Supply Chain 2018 AN EXPLORATION OF ORGANIZATIONAL BUYING BEHAVIOR IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR Kevin S. Chase University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.119 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Chase, Kevin S., "AN EXPLORATION OF ORGANIZATIONAL BUYING BEHAVIOR IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Marketing and Supply Chain. 7. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/marketing_etds/7 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Marketing & Supply Chain at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Marketing and Supply Chain by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

BGMT 640.50: Organizational Behavior Jennifer D

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi 9-2013 BGMT 640.50: Organizational Behavior Jennifer D. Smith University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Recommended Citation Smith, Jennifer D., "BGMT 640.50: Organizational Behavior" (2013). Syllabi. 1753. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/1753 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Montana - Missoula School of Business Administration Organizational Behavior- BGMT 640 Weeks 1-10, Fall Semester 2013 (I) Tues/Thurs 12:40-2:00 (II) Wednesday 6:10-9:00 Professor: Jennifer Smith Office Hours: By appointment or contact [email protected] email Telephone: (406) 493-4509 COURSE DESCRIPTION The ability to understand, predict, and improve the performance of employees and organizations is key in today’s business environment. This course focuses on some of the “soft skills” that are necessary to manage human actions in organizations. We will studyindividual the aspects related to organizational behavior (including self-awareness, personalities, individual differences, motivation, and perspectives) as well as delving intogroup the and organizational aspects, (including conflict, communication, networks, culture, and organizational structure). A particular focus will be on interpersonal skills and the development of personal strategies. Students are required to review the theories involved in the study of organizations and the people within (through readings and research) so that the focus of the course can be on learning to apply those theories and concepts to real situations (through observations, in-class discussions, and exercises/activities). -

MGT-Management

Course Descriptions MGT-Management MGT300 - Principles of Management This course provides background and insight into the human factors involved in the day-to-day and long-term operations of an organization. It is built on the management functions necessary for success in any type (profit or nonprofit) organization. The course focuses on major issues that affect today's managers, such as global environment, corporate social responsibilities and ethics, organizational culture, employee empowerment, and employee diversity. It also explores how external environments affect the operations of organizations. MGT301 - Organizational Behavior This course is designed to provide students with a multidisciplinary view of the study of behavior in organizations to better understand and manage people at work. It focuses on describing and explaining the core concepts and foundation principles that are fundamental to understanding behavior in organizations. Emphasis is placed on topics that affect individual behavior, team and group behavior and behavior of the organization itself. Behavioral questionnaires and self-assessment instruments are used to help students gain self-insights and further develop the competencies needed to be effective employees and successful managers/leaders. MGT303 - Entrepreneurship I: Small Business Fundamentals This is a management course designed to address the steps in the entrepreneurial process to establish a new business or to launch a new product line in an established organization. This course is a study of how to successfully analyze opportunities for a new venture. The contents provide the complete analytical process for establishing a new and successful operation. The new venture decision provides a compelling reason for success. This course leads up to the establishment of a complete Business Plan. -

Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-2019 Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship Jacob Martin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Martin, Jacob, "Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship" (2019). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 124. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. This dissertation, directed and approved by the candidate’s committee, has been accepted by the College of Graduate and Professional Studies of Abilene Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership Dr. Joey Cope, Dean of the College of Graduate and Professional Studies Date Dissertation Committee: Dr. First Name Last Name, Chair Dr. First Name Last Name Dr. First Name Last Name Abilene Christian University School of Educational Leadership Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership by Jacob Martin December 2018 i Acknowledgments I would not have been able to complete this journey without the support of my family. My wife, Christal, has especially been supportive, and I greatly appreciate her patience with the many hours this has taken over the last few years. I also owe gratitude for the extra push and timely encouragement from my parents, Joe Don and Janet, and my granddad Dee. -

English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution

Choosing the Partnership: English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution Ryan Bubb* I. INTRODUCTION For most of the period associated with the Industrial Revolution in Britain, English law restricted access to incorporation and the Bubble Act explicitly outlawed the formation of unincorporated joint stock com- panies with transferable shares. Furthermore, firms in the manufacturing industries most closely associated with the Industrial Revolution were overwhelmingly partnerships. These two facts have led some scholars to posit that the antiquated business organization law was a constraint on the structural transformation and growth that characterized the British economy during the period. For example, Professor Ron Harris argues that the limitation on the joint stock form was “less than satisfactory in terms of overall social costs, efficient allocation of resources, and even- 1 tually the rate of growth of the English economy.” * Associate Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. Email: [email protected]. For helpful comments I am grateful to Ed Glaeser, Ron Harris, Eric Hilt, Giacomo Ponzetto, Max Schanzenbach, and participants in the Berle VI Symposium at Seattle University Law School, the NYU Legal History Colloquium, and the Harvard Economic History Tea. I thank Alex Seretakis for superb research assistance. 1. RON HARRIS, INDUSTRIALIZING ENGLISH LAW: ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND BUSINESS ORGANIZATION, 1720–1844, at 167 (2000). There are numerous other examples of this and related arguments in the literature. While acknowledging that, to a large extent, restrictions on the joint stock form could be overcome by alternative arrangements, Nick Crafts nonetheless argues that “institutional weaknesses relating to . company legislation . must have had some inhibiting effects both on savers and on business investment.” Nick Crafts, The Industrial Revolution, in 1 THE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF BRITAIN SINCE 1700, at 44, 52 (Roderick Floud & Donald N. -

A Guide to Nonprofit Board Service in Oregon

A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE IN OREGON Office of the Attorney General A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE Dear Board Member: Thank you for serving as a director of a nonprofit charitable corporation. Oregonians rely heavily on charitable corporations to provide many public benefits, and our quality of life is dependent upon the many volunteer directors who are willing to give of their time and talents. Although charitable corporations vary a great deal in size, structure and mission, there are a number of principles which apply to all such organizations. This guide is provided by the Attorney General’s office to assist board members in performing these important functions. It is only a guide and is not meant to suggest the exact manner that board members must act in all situations. Specific legal questions should be directed to your attorney. Nevertheless, we believe that this guide will help you understand the three “R”s associated with your board participation: your role, your rights, and your responsibilities. Active participation in charitable causes is critical to improving the quality of life for all Oregonians. On behalf of the public, I appreciate your dedicated service. Sincerely, Ellen F. Rosenblum Attorney General 1 UNDERSTANDING YOUR ROLE Board members are recruited for a variety of reasons. Some individuals are talented fundraisers and are sought by charities for that reason. Others bring credibility and prestige to an organization. But whatever the other reasons for service, the principal role of the board member is stewardship. The directors of the corporation are ultimately responsible for the management of the affairs of the charity.