Artistic Production Following Brain Damage: a Study of Three Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd Position on the Sensorimotor and Social Mechanisms of Hallucinations in Healthy Participants and Patients with Parkinson’S Disease

PhD position on the sensorimotor and social mechanisms of hallucinations in healthy participants and patients with Parkinson’s Disease. Prof. Olaf Blanke Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland The LaBoratory of Cognitive Neuroscience, directed By Olaf Blanke (https://www.epfl.ch/laBs/lnco/), has an open position for a PhD student on the investigation of the sensorimotor and social brain mechanisms of a specific hallucination (presence hallucination; Blanke et al., Current Biology 2014; Arzy et al., Nature 2006) in healthy participants and in patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD). The project will couple roBotics, virtual reality (VR), experimental psychology, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and is part of a larger research project on hallucinations. Most patients with PD are not only affected by motor symptoms (e.g., tremor), but also experience hallucinations as a symptom of the disease (Lenka et al., Neurology 2019). Despite the high prevalence of patients with hallucinations, the neural mechanisms remain poorly understood. By comBining MRI-compatible roBotics (Hara et al., J Neuroscience Methods 2014) and MRI-compatible VR, the present project plans to investigate how sensorimotor and social stimulation can induce and mimic symptomatic hallucinations (in patients with PD and in healthy participants) in a fully controlled environment. The ideal candidate should have a Master degree (or equivalent) in computer science, neuroscience, medicine, psychology, or engineering, Be strongly motivated with a keen interest in cognitive-systems neuroscience and neuroimaging/signal analysis. A strong neuroimaging background (fMRI), previous research experience in the experimental psychology, and/or strong programming skills (Matlab, python, etc.) are a plus. -

How Much Are We Willing to Pay for a Fossil?

OPINION NATURE|Vol 462|24/31 December 2009 CORRESPONDENCE Goodbye to Darwin popular religious beliefs in some ‘theory of progressive change’. (1858–1925) and Otto Dix conservative societies across the In fact, the word jinhualun (1891–1969). Some milder from a contemporary eastern world. There, the writings originated in Japan in the 1870s, conditions can even enhance with vision and thoughts of intellectuals, gaining popularity in China only productivity and creativity. For however influential, are no match after appearing in Ma Junwu’s example, the metaphysical art of One night some 40 years ago, for traditional religion. later translation of Darwin’s The Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978) I was working late and alone in the For example, in Pakistan it was Origin of Species. may have been inspired by library at the Marine Biology not until 2002 that a chapter on Instead, Yan Fu coined the migraine or epilepsy. Laboratory at Woods Hole (in evolution was included for the term tianyanlun. The Chinese Kemp focuses entirely those days, the library never really first time in a school textbook, as a words tian and yan are layered in on the beholder, as though closed), searching for something result of the federal government’s meaning, with tian translatable as — to paraphrase the French in the 1882 volume of Archiv für educational reforms. The earlier ‘heaven’ and yan as ‘development’ philosopher Roland Barthes Protistenkunde. As I opened it, out decades of attempts to suppress or ‘performance’, among other (Aspen 5–6; 1967) — the birth of fell a folded page from the magazine scientific ideas were certainly not concepts. -

3. Memory Enhancement and Cognitive Engineering

3. Memory enhancement and cognitive engineering By Olaf Blanke (Professor and Bertarelli Chair in Cognitive Neuroprosthetics, EPFL), Baptiste Gauthier (Senior Researcher, EPFL) with contributions through interviews from Itzhak Fried (Professor at the Brain Research Institute, University of California Los Angeles), Johannes Gräff (Professor at the Laboratory of Neuroepigenetics) , Bryan Johnson (CEO, Kernel) and Michael Kahana (Professor for Computational Memory, University of Pennsylvania) and edited by Moheb Costandi. Key Concepts Deep Brain Stimulation is an experimental surgical procedure that involves chronic implantation of stimulating wire electrodes into deep brain structures. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Deep Brain Stimulation as a treatment for the motor symptoms of movement disorders in 1997, and since then the technique has been used to treat approximately 150,000 Parkinson’s Disease patients. It is also being used experimentally to treat various psychiatric conditions, including major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Optogenetics is an experimental technique that offers by far the most sophisticated approach to manipulating memories. Developed over the past 15 years, optogenetics involves targeting specific neuronal cell types with genetic constructs containing light-sensitive algal genes. The constructs render specific, genetically targeted sub-sets of neurons sensitive to light, so that they can be activated or inhibited with light pulses delivered into the brain by means of optical fibres. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation stimulates brain activity by inducing a magnetic field that modulates the activity of neuronal populations within a targeted region of the cerebral cortex. Developed in 1985, the technique is being investigated as a treatment for various psychiatric conditions and received FDA approval as a treatment for drug-resistant major depression in 2008. -

Neural Mechanisms of Embodiment Asomatognosia Due to Premotor Cortex Damage

OBSERVATION Neural Mechanisms of Embodiment Asomatognosia Due to Premotor Cortex Damage Shahar Arzy, MD; Leila S. Overney, PhD; Theodor Landis, MD; Olaf Blanke, MD, PhD Background: Patients with asomatognosia generally de- and motor cortices. The patient’s pathological embodi- scribe parts of their body as missing or disappeared from cor- ment for her left arm was associated with mild left poreal awareness. This disturbance is generally attributed somatosensory loss, mild frontal dysfunction, and a to damage in the right posterior parietal cortex. However, behavioral deficit in the mental imagery of human recent neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies sug- arms. gest that corporeal awareness and embodiment of body parts areinsteadlinkedtothepremotorcortexofbothhemispheres. Conclusion: Asomatognosia may also be associated with damage to the right premotor cortex. Patient: We describe a patient with asomatognosia of her left arm due to damage in the right premotor Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1022-1025 SOMATOGNOSIA IS DEFINED arm or hand. After several minutes, the pa- as a patient’s feeling that tient experienced progressive restoration of parts of his or her body are her left hand and arm starting laterally, then “missing” or have disap- medially (Figure 1C), while leaving 2 holes peared from corporeal in the middle of her hand (Figure 1D). Later awareness.A1 Evidence from patients with fo- the 2 holes fused (Figure 1E) until the arm cal brain damage suggests that asomatog- was complete again (Figure 1F), and she was nosia is linked to posterior parietal le- able to move it some minutes later. No other sions, especially of the right hemisphere, bodypartsorelementsofextrapersonalspace and generally affects the contralesional were experienced as modified. -

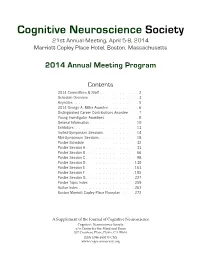

CNS 2014 Program

Cognitive Neuroscience Society 21st Annual Meeting, April 5-8, 2014 Marriott Copley Place Hotel, Boston, Massachusetts 2014 Annual Meeting Program Contents 2014 Committees & Staff . 2 Schedule Overview . 3 . Keynotes . 5 2014 George A . Miller Awardee . 6. Distinguished Career Contributions Awardee . 7 . Young Investigator Awardees . 8 . General Information . 10 Exhibitors . 13 . Invited-Symposium Sessions . 14 Mini-Symposium Sessions . 18 Poster Schedule . 32. Poster Session A . 33 Poster Session B . 66 Poster Session C . 98 Poster Session D . 130 Poster Session E . 163 Poster Session F . 195 . Poster Session G . 227 Poster Topic Index . 259. Author Index . 261 . Boston Marriott Copley Place Floorplan . 272. A Supplement of the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience Cognitive Neuroscience Society c/o Center for the Mind and Brain 267 Cousteau Place, Davis, CA 95616 ISSN 1096-8857 © CNS www.cogneurosociety.org 2014 Committees & Staff Governing Board Mini-Symposium Committee Roberto Cabeza, Ph.D., Duke University David Badre, Ph.D., Brown University (Chair) Marta Kutas, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Adam Aron, Ph.D., University of California, San Diego Helen Neville, Ph.D., University of Oregon Lila Davachi, Ph.D., New York University Daniel Schacter, Ph.D., Harvard University Elizabeth Kensinger, Ph.D., Boston College Michael S. Gazzaniga, Ph.D., University of California, Gina Kuperberg, Ph.D., Harvard University Santa Barbara (ex officio) Thad Polk, Ph.D., University of Michigan George R. Mangun, Ph.D., University of California, -

Out-Of-Body Experiences: All in the Brain?

Out-of-Body Experiences: All in the Brain? Janice M. Holden, Ed.D. University of North Texas, Denton, TX Jeffrey Long, M.D. Near-Death Experience Research Foundation, Gallup, NM Jason MacLurg, M.D. Seattle, WA ABSTRACT: In 2002, four Swiss physicians published an article in the leading scientific journal Nature claiming to have induced an out-of-body experience (OBE) through focal electrical stimulation of the brain of a patient undergoing surgical evaluation for epilepsy treatment (Blanke, Ortigue, Landis, and Seeck, 2002). The article's subtitle authors claimed that "the part of the brain that can induce out-of-body experiences has been located" (Blanke, Ortigue, Landis, and Seeck, 2002, p. 269) and the subtitle of the accompanying report on the journal's website read "stimulating brain region elicits illusion often attributed to the paranormal" (Pearson, 2002). We present arguments supporting the conclusion that the subtitle claims were not well-founded and that much research remains to be conducted to unravel the mystery of OBEs. KEY WORDS: out-of-body experience; temporal lobe; brain stimulation. A one-page print article in 2002 in the journal Nature was provocatively titled "Stimulating illusory own-body perceptions: The part of the brain that can induce out-of-body experiences has been located" (Blanke, Ortigue, Landis, and Seeck, 2002, p. 269). The Janice M. Holden, Ed.D., is Professor of Counseling and Interim Chair of the Department of Counseling, Development, and Higher Education in the College of Education at the University of North Texas in Denton, TX. Jeffrey Long, M.D., is a radiation oncologist and founder of the Near-Death Experience Research Foundation (www.nderf.org). -

Multisensory Brain Mechanisms of Bodily Self-Consciousness Olaf Blanke

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily self-consciousness Olaf Blanke http://lnco.epfl.ch/ http://cnp.epfl.ch/ Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience Center for Neuroprosthetics What is a Self ? The self seems distinct from the environment and other humans and may be described as an entity to which certain mental events and actions are ascribed. [David & Kircher, 2003] The Self in Cognitive Neuroscience Autobiographical Memory Thought: Cogito Ergo Sum Visual Mirror Recognition Bodily self-consciousness: How the brain processes signals from the body is the foundation for the self Jeannerod, Frith, Ramachandran Damasio, Craig Bodily self (consciousness) without a body Phantom limbs The physical body is NOT necessary for the experience of the bodily self. Melzack proposed “that the brain generates the experience of the body and that sensory inputs merely modulate our bodily experience.” Phantom limbs are “produced by the same brain processes that underlie the experience of the body when it is intact” [Halligan, 2002; Melzack, 1990; Ramachandran, 1993; Brugger et al., 2000] Bodily self for the entire body Are there phantom bodies and phantom selves? Out-of-body experiences: abnormal bodily self- consciousness Extracorporeal Self-location (or disembodiment) I am localized outside my body Extracorporal first-person perspective I perceive the world (and my body) from a disembodied perspective Self-identification I identify with the elevated body Neurology of out-of-body experiences Brain damage is localized -

Visual Consciousness and Bodily Self-Consciousness

CE: P.P.; WCO/280111; Total nos of Pages: 6; WCO 280111 REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Visual consciousness and bodily self-consciousness Nathan Faivrea,b,Ã, Roy Salomona,b,Ã, and Olaf Blankea,b,c Purpose of review In recent years, consciousness has become a central topic in cognitive neuroscience. This review focuses on the relation between bodily self-consciousness – the feeling of being a subject in a body – and visual consciousness – the subjective experience associated with the perception of visual signals. Recent findings Findings from clinical and experimental work have shown that bodily self-consciousness depends on specific brain networks and is related to the integration of signals from multiple sensory modalities including vision. In addition, recent experiments have shown that visual consciousness is shaped by the body, including vestibular, tactile, proprioceptive, and motor signals. Summary Several lines of evidence suggest reciprocal relationships between vision and bodily signals, indicating that a comprehensive understanding of visual and bodily self-consciousness requires studying them in unison. Keywords bodily illusions, bodily self-consciousness, body ownership, embodiment, visual consciousness INTRODUCTION model to study perceptual consciousness, consider- Brain activity causes subjective experience. It ‘feels ing its rather ‘primitive’ attributes, with both phylo- like something’ to see a rose, and this feeling is genetic and ontogenetic roots preceding those of qualitatively different from touching or smelling vision [1]. Accordingly, its functional organization it and seeing an orchid [2]. For the past 20 years, and the computational steps underlying tactile con- there have been considerable efforts to describe the sciousness are likely to be simpler compared to vision, so-called ‘neural correlates of consciousness’ (NCC), and therefore more accessible to empirical investi- which is the minimal set of neuronal events and gations and theoretical interpretations. -

13 Faculty Members and Their Research Laboratories

NEUROSCIENCENEUROSCIENCE ATAT EPFLEPFL // BMIBMI BRAIN MIND INSTITUTE BLUE BRAIN PROJECT The BMI aims to explore brain function at multiple levels: genomics, gene The Blue Brain Project began in July 2005 as a collaboration Director: Pierre J. Magistretti Director: Henry Markram expression, protein expression and handling, biochemical and metabolic between Professor Henry Markram from the Brain Mind Institute dynamics, signaling pathways, molecular biophysics of ion channels and at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) and receptors, synaptic transmission, plasticity and integration, neuronal and International Business Machines (IBM), aimed at modeling the glial composition of the brain and the micro-circuits that they form, whole neocortical column. The neocortical column represents the basic brain structural and functional circuitry, structure and functional dynamics of functional unit of the cerebral cortex in mammals that underlies sensory and motor systems, emergence of complex behavior, physical nearly all sensory and cognitive processing. These units are limits of perception, and the emergence of higher brain functions in repeated millions of times across the cortex, with the basic humans. The aim is also to study the dysfunctions of the brain focusing on structure remaining the same from the mouse to man. From its autism, schizophrenia and neurodegenerative disorders. In addition, an origins – IBM’s BlueGene/L supercomputer and 10 years of important dimension for the BMI is to merge areas of experimental work experimental data from Professor Markram’s laboratory and – with theory and modeling. The BMI has established links with Universities the project has grown to include an international multidisciplinary and Hospitals in the Lemanic area, particularly with psychiatry and team of experimentalists, modelers and computer scientists. -

Fmri Post-Doc Position on Cognitive and Psychiatric Complications in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Neurodegeneration 16.07.20, 21:17

fMRI post-doc position on cognitive and psychiatric complications in patients with mild cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration 16.07.20, 21:17 The Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) is one of the most dynamic university campuses in Europe and ranks among the top 20 universities worldwide. The EPFL employs 6,000 people supporting the three main missions of the institutions: education, research and innovation. The EPFL campus offers an exceptional working environment at the heart of a community of 16,000 people, including over 10,000 students and 3,500 researchers from 120 different countries. The Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience (Olaf Blanke: https://www.epfl.ch/labs/lnco/ ) and the Medical Image Processing Lab (Dimitri Van De Ville: https://miplab.epfl.ch/ ) open a joint open fMRI post-doc position on the early detection of memory and executive deficits and their relationship to hallucinations in patients with mild cognitive impairments and Parkinson’s disease. The position is part of a larger project between both Labs on cognitive decline in neurodegeneration, mild cognitive impairments, and health-related brain changes using cutting-edge signal analysis methods (such as innovation-driven co-activation patterns 1; toolbox for co-activation patterns 2) and a recently developed neuroengineering platform, including immersive Virtual Reality, robotically-controlled stimulations during fMRI acquisition, psychophysics. fMRI post-doc position on cognitive and psychiatric complications in patients with mild cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration https://recruiting.epfl.ch/Vacancies/1424/Description/2 Page 1 of 3 fMRI post-doc position on cognitive and psychiatric complications in patients with mild cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration 16.07.20, 21:17 Your mission : The project aims at investigating how hallucinations in the elderly and in patients with Parkinson’s disease are associated with mild cognitive impairment and dementia, using advanced neurotechnology and brain imaging data analysis in large patient populations. -

Sensorimotor Hallucinations in Parkinson's Disease

Supplementary Information Sensorimotor hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease Fosco Bernasconi*1, Eva Blondiaux*1, Jevita Potheegadoo1, Giedre Stripeikyte1, Javier Pagonabarraga2,3,4,5, Helena Bejr-Kasem2,3,4,5, Michela Bassolino1, Michel Akselrod1,6, Saul Martinez-Horta2,3,4,5, Fred Sampedro2,3,4,5, Masayuki Hara9, Judit Horvath7, Matteo Franza1, Stéphanie Konik1,6, Matthieu Bereau7,8, Joseph-André Ghika10, Pierre R. Burkhard7, Dimitri Van De Ville12,13, Nathan Faivre1,11, Giulio Rognini1, Paul Krack14, Jaime Kulisevsky2,3,4,5, and Olaf Blanke1,7 Affiliations 1. Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience, Center for Neuroprosthetics & Brain Mind Institute, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Geneva, Switzerland 2. Movement Disorders Unit, Neurology Department Sant Pau Hospital, Barcelona, Spain 3. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB), Spain 4. Centro de Investigación en Red-Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), Spain 5. Biomedical Research Institute (IIB-Sant Pau), Barcelona, Spain 6. University Hospital of Lausanne, CHUV, Lausanne, Switzerland 7. Department of Neurology, Geneva University Hospitals, Geneva, Switzerland 8. Department of Neurology, Besançon University Hospital, Besançon, France 9. Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Saitama University, Japan 10. Department of Neurology, Hôpital du Valais, Sion, Switzerland. 11. Laboratoire de Psychologie et Neurocognition, LPNC, CNRS 5105 Université Grenoble Alpes, France 12. Medical Image Processing Laboratory, Institute of Bioengineering, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland 13. Department of Radiology and Medical Informatics, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland 14. Department of Neurology, Inselspital, University Hospital and University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. 1 Authors’ contributions FB designed Study 1 and 3, collected & analyzed data, conducted clinical interviews, wrote paper; EB designed Study 2, collected & analyzed data, wrote paper; J. -

15 Brain Mechanisms of Bodily Self-Consciousness And

BRAIN MECHANISMS OF BODILY SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS AND SUBJECTIVITY: REVIEW AND OUTLOOK Olaf Blanke Bertarelli Foundation Chair in Cognitive Neuroprosthetics Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience Center for Neuroprosthetics & Brain Mind Institute Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland Department of Neurology, University Hospital, Geneva, Switzerland Abstract Recent data that have linked self-consciousness to the processing of multisensory bodily signals in human temporo-parietal and premo- tor cortex. Studies in which subjects receive ambiguous multisenso- ry information about the location and appearance of their own body have shown that activity in these brain areas reflects the conscious experience of identifying with the body (self-identification), the ex- perience of where «I» am in space (self-location), and the experience of the perspective from where «I» perceive the world (first-person perspective). These findings may form the basis for a neurobiologi- cal model of self-consciousness. In the conclusion I highlight other domains of cognitive neuroscience that are of relevance for under- standing higher-order forms of self-consciousness and the relevance of these findings for cognitive neuroprosthetics. 15 Introduction Human adults experience a «real me» that «resides in my body» and is the subject or «I» of experience and thought. This is self-consciousness, the feeling that conscious experiences are bound to the self and belong to «somebody». It is this unitary entity, the «I», that is often considered to be one of the most astonishing features of the human mind. Recent ap- proaches to investigate self-consciousness have targeted brain mecha- nisms that process bodily signals (i.e. bodily self-consciousness)1-6,54.