Slum Upgrading and Participation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Costa Rica Crime & Safety Report

2020 Costa Rica Crime & Safety Report This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Embassy in San José. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in Costa Rica. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s Costa Rica country page for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private- sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses Costa Rica at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to crime. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System. Overall Crime and Safety Situation Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed San José as being a HIGH-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government interests. Exercise increased caution in central Limon, Liberia, the Desamparados neighborhood in San Rafael, and the Pavas and Hospital neighborhoods in San José due to crime. Crime is a concern in Costa Rica; non-violent petty crime occurs most frequently. All individuals are potential targets for criminals. The majority of crime and safety threats to the U.S. official and private communities are opportunistic acts of theft. U.S. citizens commonly report theft of travel documents. Theft is common in highly populated and tourist areas, particularly in cases where individuals are not watching personal belongings closely, to include leaving items on beaches or in parked vehicles. -

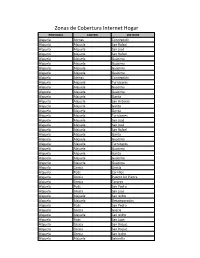

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Draft Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Improvements to the Tijuana River Flood Control Project

Draft Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement Improvements to the Tijuana River Flood Control Project Lead Agency: United States Section International Boundary and Water Commission El Paso, Texas Cooperating Agency: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Los Angeles District, California Technical Support: August 2007 PARSONS Austin, Texas Cover Sheet PROGRAMMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT IMPROVEMENTS TO THE TIJUANA RIVER FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT (X) Draft ( ) Final Lead Agency The USIBWC will apply the programmatic evaluation as an overall guidance for future United States Section, International environmental evaluations of individual Boundary and Water Commission improvement projects, the implementation (USIBWC) of which is anticipated or possible within a El Paso, Texas 20-year timeframe. Cooperating Agencies Other Requirements Served U.S. Army Corps of Engineers This PEIS is intended to serve other Abstract environmental review and consultation requirements pursuant to 40 CFR The USIBWC anticipates the need to 1502.25(a) improve capabilities or functionality of the Tijuana River Flood Control Project. Comments Submittal Improvement measures associated with the The Draft PEIS will be available for a project core mission of flood protection and 45-day public review period. Comments boundary stabilization are evaluated under should be directed by September 24, 2007 the Enhanced Operation and Maintenance to: (EOM) Alternative, while measures in support of local or regional initiatives for Mr. Daniel Borunda increased utilization of the project or to Environmental Management Division improve environmental conditions are USIBWC evaluated under the Multipurpose Project 4171 North Mesa St., C-100 Management (MPM) Alternative. El Paso, Texas 79902 This Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement (PEIS) evaluates potential Date of Draft Availability to USEPA and environmental consequences alternatives the Public: under consideration for improvement of the Tijuana River Flood Control Project. -

ADEQUATE HOUSING and SLUM UPGRADING Monitoring and Reporting the Sdgs | ADEQUATE HOUSING and SLUM UPGRADING

` MODULE 1 ADEQUATE HOUSING AND SLUM UPGRADING Monitoring and Reporting the SDGs | ADEQUATE HOUSING AND SLUM UPGRADING ADEQUATE HOUSING AND SLUM UPGRADING TARGET 11.1: By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums Indicator 11.1.1: Proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing Suggested Citation: UN-Habitat (2018). SDG Indicator 11.1.1 Training Module: Adequate Housing and Slum Upgrading. United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi. 2 | Indicator 11.1.1 Training Module Monitoring and Reporting the SDGs | ADEQUATE HOUSING AND SLUM UPGRADING SECTION 1: 1.1 Background INTRODUCTION Sixty per cent of the global population will live in cities by 2030, with 90% of urban growth in coming decades likely to occur in low- and middle-income countries. Current urbanization trends indicate that an additional three billion people will be living in cities by 2050, increasing the urban share of the world’s population to two-thirds. In fact, 95% of the growth in urban areas in the next two decades will occur in cities, making them home to more than 4 billion people, and translating to about 80% of future urban population. The steady trend towards urbanization will influence virtually every facet of human endeavor in the coming years, including health, economic, social, and environmental. In many parts of the world, especially in developing countries, high rates of urbanization have unfolded in context of stagnating economies and poor planning and governance, creating a new face of abject poverty concentrated in slums or informal settlements in major cities. -

May 18, 2012 Projection of the CARB 2008 Emissions Inventory For

May 18, 2012 Projection of the CARB 2008 Emissions Inventory for Northern Mexico to Future Years INTRODUCTION In ERG (2009), the baseline 1999 national emissions inventory for Mexico was projected to the years 2008, 2012, and 2030. These projections were used to extrapolate the year 2008 emissions inventory for Baja California (CARB, 2012) to the years 2023 and 2030 for air quality analyses within southern California. In their analyses, ERG (2009) used projections of population growth, industrial development, and land use planning to estimate future emissions; in many cases, by individual source classification code (SCC). However, this level of detail is beyond the scope of what can be done in the short term. Also, while the emissions inventory generated for Baja California by the CARB (2012) used ERG’s year 2008 inventory as a starting point, the final inventory was appreciably different. In this analysis, the relative changes in emissions growth quantified by ERG for the years 1999, 2008, and 2030 were used to prepare emissions-response curves, which were then used to scale the CARB 2008 inventory to future years. PREPARATION OF EMISSIONS RESPONSE FUNCTIONS The emissions inventories developed by ERG (2009) for the years 1999, 2008, 2012, and 2030 were provided in four broadly defined groups: on-road, non-road, point, and non-point emissions. Within these groups, emissions for CO, NOx, SOx, COT (VOC), PM10 (PM), and NH3 were provided by State and by Municipality. To avoid being confounded by differences in spatial distributions and source classifications, emissions within each group were summed by State and Municipality. -

Squatting – the Real Story

Squatters are usually portrayed as worthless scroungers hell-bent on disrupting society. Here at last is the inside story of the 250,000 people from all walks of life who have squatted in Britain over the past 12 years. The country is riddled with empty houses and there are thousands of homeless people. When squatters logically put the two together the result can be electrifying, amazing and occasionally disastrous. SQUATTING the real story is a unique and diverse account the real story of squatting. Written and produced by squatters, it covers all aspects of the subject: • The history of squatting • Famous squats • The politics of squatting • Squatting as a cultural challenge • The facts behind the myths • Squatting around the world and much, much more. Contains over 500 photographs plus illustrations, cartoons, poems, songs and 4 pages of posters and murals in colour. Squatting: a revolutionary force or just a bunch of hooligans doing their own thing? Read this book for the real story. Paperback £4.90 ISBN 0 9507259 1 9 Hardback £11.50 ISBN 0 9507259 0 0 i Electronic version (not revised or updated) of original 1980 edition in portable document format (pdf), 2005 Produced and distributed by Nick Wates Associates Community planning specialists 7 Tackleway Hastings TN34 3DE United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)1424 447888 Fax: +44 (0)1424 441514 Email: [email protected] Web: www.nickwates.co.uk Digital layout by Mae Wates and Graphic Ideas the real story First published in December 1980 written by Nick Anning by Bay Leaf Books, PO Box 107, London E14 7HW Celia Brown Set in Century by Pat Sampson Piers Corbyn Andrew Friend Cover photo by Union Place Collective Mark Gimson Printed by Blackrose Press, 30 Clerkenwell Close, London EC1R 0AT (tel: 01 251 3043) Andrew Ingham Pat Moan Cover & colour printing by Morning Litho Printers Ltd. -

The Roadto DEVELOPMENT In

MUNICIPAL SUMMARY OF SOCIAL INDICATORS IN COCHABAMBA NATIONWIDE SUMMARY OF SOCIAL INDICATORS THE ROAD TO DEVELOPMENT IN Net primary 8th grade of primary Net secondary 4th grade of Institutional Map Extreme poverty Infant mortality Municipality school coverage completion rate school coverage secondary completion delivery coverage Indicator Bolivia Chuquisaca La Paz Cochabamba Oruro Potosí Tarija Santa Cruz Beni Pando Code incidence 2001 rate 2001 2008 2008 2008 rate 2008 2009 1 Primera Sección Cochabamba 7.8 109.6 94.3 73.7 76.8 52.8 95.4 Extreme poverty percentage (%) - 2001 40.4 61.5 42.4 39.0 46.3 66.7 32.8 25.1 41.0 34.7 2 Primera Sección Aiquile 76.5 87.0 58.7 39.9 40.0 85.9 65.8 Cochabamba 3 Segunda Sección Pasorapa 83.1 75.4 66.9 37.3 40.5 66.1 33.4 Net primary school coverage (%) - 2008 90.0 84.3 90.1 92.0 93.5 90.3 85.3 88.9 96.3 96.8 Newsletter on the Social Situation in the Department | 2011 4 Tercera Sección Omereque 77.0 72.1 55.5 19.8 21.2 68.2 57.2 Completion rate through Primera Sección Ayopaya (Villa de th 77.3 57.5 87.8 73.6 88.9 66.1 74.8 77.8 74.4 63.1 5 93.0 101.7 59.6 34.7 36.0 106.2 67.7 8 grade (%) - 2008 Independencia) CURRENT SITUATION The recent years have been a very important nificant improvement in social indicators. -

Student Power in World Evangelism (Urbana 1970) David Howard

Student Power in World Evangelism (Urbana 1970) David Howard http://www.urbana.org/_articles.cfm?RecordId=624 World evangelism - Why? How? Who? These are the questions we are concerned with during Urbana 70. As we seek solutions, we will naturally be looking at the world around us and at the future that lies ahead. For unless we can understand the world we live in, we will be in a poor position to talk about evangelizing that world. By the same token, unless we can understand what produced the world we live in - that is, where we came from and why we stand at this particular juncture in history - we can scarcely hope to understand our present age. I am well aware that it is in vogue today to call this the Now Generation. We are intensely concerned with the here and now. We want to be where the action is today, not where it was yesterday, nor where it will be tomorrow. Yesterday is gone forever, and who knows if tomorrow will ever come? So I can live only in and for today. From one standpoint, this is a noble aspiration. However, proper focus on the present requires a proper focus on the past from which we have come and on the future to which we are heading. A man is not only lost when he does not know where he is going; he is also lost when he does not know where he has come from. The very mention of the word history may already have caused some of us to turn off our hearing aids. -

Financing Metropolitan Governments in Developing Countries

Financing Metropolitan Governments Bahl Linn in Developing Countries Wetzel Edited by Roy W. Bahl, Johannes F. Linn, and Deborah L. Wetzel Financing Metropolitan Governments Governments Metropolitan Financing or the first time in human history, more people live in urban rather than rural Fareas; the number of metropolitan cities in developing countries far exceeds those in advanced economies; and the governance of megacities is of greater importance as national finances have become precarious. This book skillfully weaves together the theory and history of metropolitan finance with illustrative case studies, which offer deep insights into metropolitan financial governance in Brazil, India, and China, among in other countries. The authors address the politics of metropolitan government, the mys- Developing Countries Developing teries of the underutilized instrument of the property tax, and the question of financ- ing urban infrastructure. This is an indispensable volume for policy makers and for those who care about the future of metropolitan cities. — Rakesh Mohan Executive Director, International Monetary Fund he economic and political future of the developing world depends crucially on the Tongoing processes of urbanization. The essays in this volume, by leading scholars Financing Metropolitan intimately associated with these issues, provide a deep analysis of the critical role of metropolitan governance and financial structure in urbanization. It is the best treatment available: a wide-ranging and penetrating exploration of both theory and practice. Governments in — Wallace E. Oates Professor of Economics, Emeritus Developing Countries University of Maryland Edited by his well-written and informative book will put local governments, especially in Roy W. Bahl, Johannes F. Linn, and Deborah L. -

Date: Sat, Dec 29, 2012 at 9:43 AM

From: Jones, Allen To: Hall, Vince; Shepard, Tom; McCormack, Irene; DRBOB Subject: AJ"s edits to first draft of State of the City address Date: Saturday, January 05, 2013 4:29:20 PM Attachments: Attached are my revised additions to the SoC in response to our discussion today. Allen ---------- Forwarded message ---------- From: Tom Shepard <[email protected]> Date: Sat, Dec 29, 2012 at 9:43 AM Subject: First draft of State of the City speech To: Vince Hall < > Attached is a first draft of the State of the City speech. As I mentioned when we first discussed this, the draft should be viewed as a framework, not a completed document. I’ve highlighted in yellow paragraphs that are still needed but that are outside my areas of expertise. Among these, I’ve already asked Chris Frahm to give us a paragraph on water policy, which she has promised by next week. Also, please note that it has been a custom in some previous SoCs to solicit suggestions from the council members about specific initiatives they would like the mayor to call out and for which they would like to be recognized. Not sure if you want to do this, but if so the appropriate place would be right after Bob’s recognition of them in the current draft. To expedite the process of completing this, I suggest we schedule a meeting with Bob sometime this next week to go over the draft, get his feedback, and make assignments for additional items that need to be added. I stand ready to revise, add, delete (or in any other way you direct) take responsibility for ensuring Bob ends up with a final product with which he is satisfied. -

Slum Upgrading and Health Equity

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Slum Upgrading and Health Equity Jason Corburn * and Alice Sverdlik Department of City and Regional Planning & School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-510-643-4790 Academic Editor: Paul B. Tchounwou Received: 14 November 2016; Accepted: 17 March 2017; Published: 24 March 2017 Abstract: Informal settlement upgrading is widely recognized for enhancing shelter and promoting economic development, yet its potential to improve health equity is usually overlooked. Almost one in seven people on the planet are expected to reside in urban informal settlements, or slums, by 2030. Slum upgrading is the process of delivering place-based environmental and social improvements to the urban poor, including land tenure, housing, infrastructure, employment, health services and political and social inclusion. The processes and products of slum upgrading can address multiple environmental determinants of health. This paper reviewed urban slum upgrading evaluations from cities across Asia, Africa and Latin America and found that few captured the multiple health benefits of upgrading. With the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) focused on improving well-being for billions of city-dwellers, slum upgrading should be viewed as a key strategy to promote health, equitable development and reduce climate change vulnerabilities. We conclude with suggestions for how slum upgrading might more explicitly capture its health benefits, such as through the use of health impact assessment (HIA) and adopting an urban health in all policies (HiAP) framework. Urban slum upgrading must be more explicitly designed, implemented and evaluated to capture its multiple global environmental health benefits. -

“Diagnosing an “Unholy Alliance”: the Radical Black Evangelical Critique of White Evangelical Nationalism”

SHARP, BLACK THEOLOGY PAPERS, VOL. 4, NO. 1 (2018) “Diagnosing an “Unholy Alliance”: The Radical Black Evangelical Critique of White Evangelical Nationalism” Isaac Sharp* ABSTRACT Largely forgotten by black theology and evangelical studies scholars alike, the “radical black evangelical” movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s was organized primarily as an explicit critique of and alternative to a white evangelical culture shot through with racism. This paper argues that a number of these “new black evangelical” thinkers—figures like Tom Skinner, William Bentley, and William Pannell—not only diagnosed the un-interrogated white cultural assumptions of mainstream U.S. American evangelicalism, they also offered trenchant critiques of white evangelicalism’s entanglement with U.S. American civil religion. Such critiques, I will further suggest, presciently prefigured much of the contemporary “identity crisis” in U.S. American evangelicalism by more than four decades. INTRODUCTION In thE first Edition of thE first voluME of Wilmore and ConE’s landMark Black Theology: A Documentary History, 1966-1979, in his Essay, “ThE NEw Black EvangElicals,” Ronald C. PottEr explained that, sometiMe during the late 1960s, a “new breed of Black Evangelicals” had EMerged, laMEnted that, “to date little if anything has bEEn written about thE history, thEology, and current debate among” this group, and aiMed to rEMedy this oversight. Recognizing that, despite holding thEologically EvangElical bEliefs, thE vast Majority of thE “MainlinE Black churchEs” wEre