Did the New Orleans School Reforms Increase Segregation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Candidate's Report

CANDIDATE’S REPORT (to be filed by a candidate or his principal campaign committee) 1.Qualifying Name and Address of Candidate 2. Office Sought (Include title of office as OFFICE USE ONLY well DESIREE CHARBONNET Report Number: 70458 Mayor 3860 Virgil Blvd. Orleans Date Filed: 4/30/2018 New Orleans, LA 70122 City of New Orleans Report Includes Schedules: Schedule A-1 Schedule A-2 Schedule A-3 Schedule B 3. Date of Primary 10/14/2017 Schedule E-1 This report covers from 10/30/2017 through 12/18/2017 4. Type of Report: X 180th day prior to primary 40th day after general 90th day prior to primary Annual (future election) 30th day prior to primary Supplemental (past election) 10th day prior to primary 10th day prior to general Amendment to prior report 5. FINAL REPORT if: Withdrawn Filed after the election AND all loans and debts paid Unopposed 6. Name and Address of Financial Institution 7. Full Name and Address of Treasurer (You are required by law to use one or more CYNTHIA C BERNARD banks, savings and loan associations, or money 1650 Kabel Drive market mutual fund as the depository of all New Orleans, LA 70131 REGIONS BANK 400 Poydras St. New Orleans, LA 70130 9. Name of Person Preparing Report PHILIP W REBOWE, CPA Daytime Telephone 504-236-0004 10. WE HEREBY CERTIFY that the information contained in this report and the attached 8. FOR PRINCIPAL CAMPAIGN COMMITTEES ONLY schedules is true and correct to the best of our knowledge, information and belief, and that no a. -

2020 Mardi Gras Extravaganza National Hotel List

2020 Mardi Gras Extravaganza National Hotel List - Alphabetical Hotel List - Distance HOTEL ADDRESS Distance HOTEL ADDRESS Distance AC Hotel New Orleans Bourbon 221 Carondelet Street The Mercantile Hotel 727 South Peters Street New Orleans, LA 1.3 New Orleans, LA 0.2 70130 70130 Ace hotel 600 Carondelet Street Hilton Garden Inn Convention Center 1001 South Peters New Orleans, LA 0.7 Street New Orleans, LA 0.3 70130 70130 Blake New Orleans 500 St. Charles Avenue Hyatt Place Convention Center 881 Convention Center New Orleans, LA 1.1 Blvd. New Orleans, LA 0.4 70130 70130 Cambria Hotel New Orleans 632 Tchoupitoulas Embassy Suites Convention Center 315 Julia Street New Downtown Warehouse District Street New Orleans, LA 0.9 Orleans, LA 70130 0.6 70130 Chateau LeMoyne 301 Dauphine Steet Hampton Inn and Suites New Orleans 1201 Convention New Orleans, LA 1.3 Convention Center Center Blvd. New 0.6 70112 Orleans, LA 70130 Country Inn and Suites Metairie 2713 North Causeway Ace hotel 600 Carondelet Street Blved. Metairie, LA 7.8 New Orleans, LA 0.7 70002 70130 Crowne Plaza New Orleans French Omni Riverfront Hotel 701 Convention Center 739 Canal Street New Quarter 1.3 Blvd. New Orleans, LA 0.7 Orleans, LA 70130 70130 DoubleTree New Orleans 300 Canal Street New Queen and Crescent 344 Camp Street New 1 0.7 Orleans, LA 70130 Orleans, LA 70130 Drury Inn and Suites Hilton New Orleans Riverside Two Poydras Street 820 Poydras Street New 1.2 New Orleans, LA 0.8 Orleans, LA 70112 70130 Embassy Suites Convention Center 315 Julia Street New LaQuinta New Orleans Downtown 301 Camp Street New 0.6 0.8 Orleans, LA 70130 Orleans, LA 70130 Four Points by Sheraton 541 Bourbon Street Westin 100 Rue Iberviller New New Orleans, LA 1.6 Orleans, LA 70130 0.8 70130 Hampton Inn and Suites New Orleans 1201 Convention Cambria Hotel New Orleans 632 Tchoupitoulas Convention Center Center Blvd. -

Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been

Geographies of New Orleans Fifty Years After Riverfront Expressway Cancellation, Shuddering at the New Orleans That Could Have Been Richard Campanella Geographer, Tulane School of Architecture [email protected] Published in the New Orleans Picayune-Advocate, August 12, 2019, page 1. Fifty years ago this summer, reports from Washington D.C. reached New Orleans that John Volpe, secretary of the Department of Transportation under President Richard Nixon, had cancelled the Riverfront Expressway—the high-speed, elevated interstate slated for the French Quarter. The stunning news, about a wildly controversy plan that had divided the community for years, was met with elation by the city’s growing preservationist movement, and head-shaking disappointment by local leaders in both the public and private sectors. A half-century on, the cancellation and the original proposal invite speculation —part mental exercise, part cautionary tale—about what greater New Orleans might look like today had the Riverfront Expressway gone forward. And it very nearly did: conventional wisdom at the time saw the new infrastructure as an inevitable step toward progress, following the lead of many other waterfront cities, including New York, San Francisco, and Seattle. But first, a recap on how the New Orleans plan got to Volpe’s desk. Rendering from Robert Moses' Arterial Plan for New Orleans, 1946, page 11, courtesy collection of R. Campanella The initial concept for the Riverfront Expressway emerged from a post-World War II effort among state and city leaders to modernize New Orleans’ antiquated regional transportation system. Toward that end, the state Department of Highways hired the famous—many would say infamous—New York master planner Robert Moses, who along with Andrews & Clark Consulting Engineers, released in 1946 his Arterial Plan for New Orleans. -

General Parking

NINE MINUTES FROM PARKING POLICIES FOR GENERAL PARKING MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME There is no general parking for vehicles, • 1000 Poydras Street MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME RVs, buses and limousines for the • 522 S Rampart Street PASS HOLDERS National Championship Game. All lots The failure of any guests to obey the surrounding the Mercedes-Benz 10 MINUTES FROM instructions, directions or requests of Superdome will be pass lots only. MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME event personnel, stadium signage or Information regarding additional • 1000 Perdido Street management’s rules and regulations parking near the Mercedes-Benz Additional Parking lots can be found may cause ejection from the event Superdome can be found below. at parking.com. parking lots at management’s discretion, and/or forfeiture and cancellation of the parking PREMIUM PARKING LOTS RV RESORTS pass, without compensation. FIVE MINUTES FROM FRENCH QUARTER RV RESORT MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME 10 MINUTES FROM TAILGATING • 1709 Poydras Street MERCEDES- BENZ SUPERDOME Tailgating in Mercedes- Benz 500 N. Claiborne Avenue Superdome lots is prohibited for the NINE MINUTES FROM New Orleans, LA 70112 National Championship Game. MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME Phone: 504.586.3000 • 400 Loyola Avenue Fax: 504.596.0555 TOWING SERVICE Email: [email protected] For towing services and assistance, 10 MINUTES FROM Website: fqrv.com please call 504-522-8123. Please raise MERCEDES-BENZ SUPERDOME your car hood and/or notify an officer • 2123 Poydras Street THREE OAKS AND A PINE RV PARK at any lot entrance. • 400 S Rampart Street 15–20 MINUTES FROM • 415 O’Keefe Avenue MERCEDES- BENZ SUPERDOME DROP-OFF AND 7500 Chef Menteur Highway • 334 O’Keefe Avenue PICK UP AREAS New Orleans, LA 70126 Guests can utilize the drop off and pick Additional parking lots can be found Phone: 504.779.5757 up area at the taxi drop off zone on at premiumparking.com. -

Warren Commission, Volume XXIII: CE 1911

2 NO 89-69:.Jas NO 80-69 :jas 1963, the following individuals GEORGE BLESTEL, Photographer, On November 29, The Ad Shop,_1201 South Rampart Street ; war& interviewed at their place. of employment, and all was never employed by them, advised that LEE H. MVIALD Clerk-Receptionist, never applied.~or .ompjpymept with their concern, and was Urs . GLORIA STYRND, E. S. Upton Printing Company, unknown to them until they began reading about him in the 746 Carondelet Street ; newspapers : Mrs . C. FRANCK HOFFMAN, Partner and Manager, LAWRENCE S:JITH, Production Manager, Franckle .Studio, 926 Poydras Street, Now E. S. Upton Printing Company, Orleans, Louisiana; 746 Carondelet Street ; RICHARD RELF, Manager, Rolf Studios, ALONZO EMERSON, Office Manager, Inc ., 113.Royal Street, Now Orleans, Lou3.siana ; t,morican Metals, successor to American Sheet Metal Works, Red SWood, 4401 Bienville Avenue ; ELIZABETH POLIT, Proprietor,Avenue, 1341 Elysian-Fields Now Orleans, Louisiana, who advised that her building L. L. MC INTYRE, Manager, was once occupied by South Central Studio . Electrolux Corporation, 1935 Tulane Avenue ; PEDRO CASANAVE, Proprietor, Pedro Art Studio, Manager, 5112 Freret Street, Now Orleans, Louisiana ; BEN SMITH, 'Electrolux Corporation, 3407 Metairie Road, Mrs at 616 North Rampart Street ; . i . L. TILLON, Lee Tillon Studio, formerly located 1504 South Carrollton Avenue, Now Orleans, Louisiana; Mrs . FRANK RENTON, Bookkeeper, Printing Press, Inc-, Mrs . GISELE SCHULTZ, Proprietor, 518 Conti Street ; Schultz Bookkeeping, 4228 South Roman Street, BENNY LA BRUYE-RE, Manager, New Orleans, Louisiana ; Printers Supply Mart, ; Mrs . THOMAS 131,RBERITO who advised that her 610 Magazine Street a photographic studio, but that boncorn is tot JR ., Manager, her husband, THOW.S BARBERITO, is an independent JUDSON CRANE, Crane Shoes, 1726 Tulane Avenue ; accountant wlio .works .out-of .his home, 1007 Dwm. -

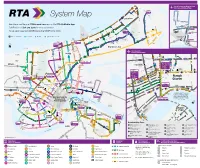

System Map 63 Paris Rd

Paris Rd. 60 Morrison Hayne 10 CurranShorewood Michoud T 64, 65 Vincent Expedition 63 Little Woods Paris Rd. Michoud Bullard North I - 10 Service Road Read 62 Alcee Fortier Morrison Lake Pontchartrain 17 Vanderkloot Walmart Paris Rd. T 62, 63, Lake Forest Crowder 64, 65 510 Dwyer Louis Armstrong New Orleans Lakefront Bundy Airport Read 63 94 60 International Airport Map Bullard Hayne Morrison US Naval 16 Joe Yenni 65 Joe Brown Reserve 60 Morrison Waterford Dwyer 64 Hayne 10 Training Center North I - 10 Service Road Park Michoud Old Gentilly Rd. Michoud Lakeshore Dr. Springlake CurranShorewood Bundy Pressburg W. Loyola W. University of SUNO New Orleans East Hospital 65 T New Orleans Downman 64, 65 T 57, 60, 80 62 H Michoud Vincent Loyola E. UNO Tilford Facility Expedition 80 T 51, 52, Leon C. Simon SUNO Lake Forest64 Blvd. Pratt Pontchartrain 55, 60 Franklin Park Debore Harbourview Press Dr. New Orleans East Williams West End Park Dwyer 63 Academy Robert E. Lee Pressburg Park s Paris St. Anthony System Map 63 Paris Rd. tis Pren 45 St. Anthony Odin Little Woods 60 10 H Congress Michoud Gentilly 52 Press Bullard W. Esplanade Bucktown Chef Menteur Hwy. Fillmore Desire 90 57 65 Canal Blvd. Mirabeau 55 32nd 51 Old Gentilly Bonnabel 15 See Interactive Maps at RTAforward.com and on the RTA GoMobile App. Duncan Place City Park y. Chef Menteur / Desire North I - 10 Service Road 5 Hw 62 Pontchartrain Blvd. Harrison Gentilly 94 ur Read 31st To Airport Chef Mente T 62, 63, 64, 65, 80, 94 Alcee Fortier 201 Clemson 10 Gentilly To Downtown MetairieMetairie Terrace Elysian Fields Fleur de Lis Lakeview St. -

New Orleans 2032 MTP.Pdf (1.140Mb)

Metropolitan Transportation Plan NewOrleans Urbanized Area F Y 2 0 3 2 Regional Planning Commission Jefferson, Orleans Plaquemines, St. Bernard and St.Tammany Parishes, Louisiana June 12, 2007 Metropolitan Transportation Plan New Orleans Urbanized Area Regional Planning Commission 1340 Poydras Street, Suite 2100 New Orleans, LA 70112 504-568-6611 504-568-6643 (fax) www: norpc.org [email protected] The preparation of this document was fi nanced in part through grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration in accordance with the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Effi cient Transportation Equity Act - A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU; P.L. 109-59). Contents Chapter 1 Introduction and Overview of the Planning Process Introduction--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2 Transportation Philosophy in SAFETEA-LU---------------------------------------------------------- 3 The Metropolitan Planning Organization----------------------------------------------------------- 4 Statutory Authority for Plan Development---------------------------------------------------------- 5 Hurricane Katrina--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Metropolitan Transportation Plan-------------------------------------------------------------------- 8 Metropolitan Planning Process----------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 Safety Conscious Planning----------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Where the Locals Go

Where The Locals Go Stone Pigman's Top New Orleans Picks Where The Locals Go 1 The lawyers of Stone Pigman Walther Wittmann L.L.C. welcome you to the great city of New Orleans. Known around the world for its food, nightlife, architecture and history, it can be difficult for visitors to decide where to go and what to do. This guide provides recommendations from seasoned locals who know the ins-and-outs of the finest things the city has to offer. "Antoine’s Restaurant is the quintessential classic New Orleans restaurant. The oldest continuously operated family owned restaurant in the country. From the potatoes soufflé to the Baked Alaska with café Diablo for dessert, you are assured a memorable meal." (713 St. Louis Street, New Orleans, LA 70130 (504) 581-4422) Carmelite Bertaut "My favorite 100+ year old, traditional French Creole New Orleans restaurant is Arnaud’s. It's a jacket required restaurant, but has a causal room called the Jazz Bistro, which has the same menu, is right on Bourbon Street, and has a jazz trio playing in the corner of the room." (813 Bienville Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70112 (504) 523-5433) Scott Whittaker "The food at Atchafalaya is delicious and the brunch is my favorite in the city. The true standout of the brunch is their build-your-own bloody mary bar. It has everything you could want, but you must try the bacon." (901 Louisiana Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70115 (504) 891-9626) Maurine Wall "Chef John Besh’s restaurant August never fails to deliver a memorable fine dining experience. -

Two Saints 857 & 867 St

Two Saints 857 & 867 St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans, LA Overview Site Plan Aerial Nearby Retail Landmarks N.O. Districts Downtown Demos Ground Floor Retail For Lease Property Overview • 1,000 SF – 17,750 SF Available Ground Floor Commercial Space • Up to 50,000 SF Available if combined with adjacent The Garage Development • Location – Infill location nestled between the Warehouse and South Market Districts, well over 600 apartments to be built on the same block by 2020 • World Famous St. Charles Avenue Streetcar – 3.5 Million people ride past the site every year • Primary ingress to the heart of New Orleans – 7.5 Million people drive past the site every year • Flexible Proportions – Nearly 17,750 SF of uninterrupted space • Reduced CAM Charges – Restoration Tax Abatement Nearby Landmarks • South Market District • New Orleans Culinary and Hospitality Institute (NOCHI) Executive Summary • National World War II Museum New Orleans Advocate Newspaper Boasting 110 feet of frontage on St. Charles Avenue and 134 feet on St. Joseph Street, Two Saints • Art Galleries along Julia Street • Office will be a first-of-its-kind Social and Co-Living complex. The project will feature over 17,000 SF of VIEW FROM INTERSECTION OF ST. CHARLES AVE. + ST. JOSEPH ST. 05/30/18 • Rouses Market TWO SAINTS|SOCIALground-floor LIVING commercial space, 65 furnished shared apartments, and a communal lobby, as well • Greater New Orleans Foundation as ample bicycle and vehicular parking. • Ace Hotel Office • The Outlet Collection at Riverwalk The development sits in a prime Warehouse District corridor, capturing the egress of the downtown commuter, fronting the famous St. -

New Orleans C L a S S - a Office Space Opportunities

DOWNTOWN New Orleans C l a s s - A Office Space Opportunities June 10, 2020 1 Class-A Office Space :: Downtown New Orleans Index of Opportunities Property Name Page No. Hancock Whitney Center (One Shell Square) 5. Place St Charles 12. Energy Centre 19. Pan American Life Center 30. One Canal Place 36. Regions Center | 400 Poydras 51. First Bank and Trust Tower 59. Benson Tower 68. 1515 Poydras Building 70. Entergy Corp. Building 79. DXC.technology Building 82. 1555 Poydras Building 89. Poydras Center 96. 1250 Poydras Plaza 105. 1010 Common Building 109. Orleans Tower | 1340 Poydras 111. 2 Downtown New Orleans Office Market Overview: Downtown New Orleans offers an affordable Class-A office market totaling 8.9 million square feet. Significant new office leases include the following: Hancock-Whitney Bank, seven floors at Hancock Whitney Center (One Shell Square) Accruent, a technology firm, leased an entire floor, 22,594 square feet, at 400 Poydras DXC.Technology announced a long term lease at 1615 Poydras, leasing two floors IMTT announced a long term lease at 400 Poydras 2020 Class A office occupancy: 87% occupied 14 total Class-A properties Average building size, 637,737 square feet $19.75 average rent per square foot) 8,928,318 total leasable Class A office space in market Class A office towers in New Orleans, ranked by total leasable square feet: Hancock Whitney Center 92% leased 1,256,991 SF Place St Charles 91% leased 1,004,484 SF Energy Centre 85% leased 761,500 SF Pan-American Life Center 83% leased 671,833 SF One Canal Place 82% leased 630,581 SF Regions Center/400 Poydras 86% leased 608,608 SF First Bank & Trust Tower 89% leased 545,157 SF Benson Tower 99% leased 540,208 SF 1515 Poydras Building 59% leased 529,474 SF Entergy Corp. -

VISITORS GUIDE to the JOHN MINOR WISDOM COURT of APPEALS BUILDING

VISITORS GUIDE to THE JOHN MINOR WISDOM COURT OF APPEALS BUILDING A Service of the Fifth Circuit Library System Public Entrance: 600 Camp Street Front Door Security: 310-7791 Court Web Site: www.ca5.uscourts.gov Security Guidelines - A valid, official photo I.D. is required - “Valid and Official” means federal, state, or municipal I.D. cards or licenses that contain a picture. Photo I.D.’s such as ‘Sam’s Club’ cards are not acceptable. - No tape recording or video recording devices are permitted - Guards do not have storage facilities to hold any items - No cameras - CELL PHONES are permitted, but must be OFF inside the courtrooms - No weapons of any kind, including pocket knives and mace - Laptop Computers are acceptable - Handicapped Access available on Capdeville St., push buzzer, or call ahead: (504) 310-7791 Transportation United Cab: 522-9771 - One way from CBD to airport = +/- $29.00 Airport Shuttle: 522-3500 - One way from CBD to airport = +/- $13.00 Advance reservations available online: www.neworleans Directions to the John Minor Wisdom Court of Appeals Building The building at 600 Camp St. can be reached by taking Canal St. or Poydras St. southeast toward the river and turning right onto either St. Charles Ave., or two blocks further right onto Magazine Street. The building is directly across from Lafayette Square which is bordered by Maestri Place, St. Charles, and Camp St. The building itself is bordered by Camp St., Poydras St., Magazine St., and Capdeville St. Coming from East New Orleans - Merge onto I-10 West. - Take EXIT 235B toward Canal St. -

LOUISIANA STATE BAR ASSOCIATION HOUSE of DELEGATES 2019-2020 0BFIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT (14 Seats) Parish of Caddo Claude W. Book

LOUISIANA STATE BAR ASSOCIATION HOUSE OF DELEGATES 2019-2020 FIRST0B JUDICIAL DISTRICT (14 seats) Parish of Caddo Claude W. Bookter, Jr., 401 Edwards Street, Suite 2100, Shreveport, LA 71101-5544 Clinton M. Bowers, PO Box 52866, Shreveport, LA 71135 James L. Fortson, Jr., PO Box 7691, Shreveport, LA 71137-7691 Stephen Christopher Fortson, 401 Edwards Street, Suite 1000, Shreveport, LA 71101-3289 Daryl Gold, 3604 Line Avenue, Shreveport, LA 71104 W. James Hill III, 8570 Business Park Drive, Suite 100, Shreveport, LA 71105 Richard M. John, 3646 Youree Drive, Shreveport, LA 71105-2122 Lauren B. McKnight, 910 Pierremont Road, Suite 410, Shreveport, LA 71106 Amy Michelle Perkins, 1835 Spring Street, Shreveport, LA 71101-4239 Nyle A. Politz, 920 Pierremont Road, Shreveport, LA 71104 Joseph L. Shea, Jr., 401 Edwards Street, Suite 1000, Shreveport, LA 71101-5529 Kenneth Craig Smith, Jr., 3646 Youree Drive, Shreveport, LA 71105-2122 Scott R. Wolf, 333 Texas Street, Suite 700, Shreveport, LA 71101-5490 Paul L. Wood, PO Box 5005, Shreveport, LA 71135-5005 SECOND1B JUDICIAL DISTRICT (3 seats) Parishes of Bienville, Claiborne & Jackson Tammy2B G. Jump, 100 Courthouse Drive, Box 257, Arcadia, LA 71001 VACANT VACANT THIRD JUDICIAL DISTRICT (3 seats) Parishes of Lincoln & Union Paul Heath Hattaway, PO Box 231, Ruston, LA 71273 Albert Carter Mills IV, 192 Twin Creeks Bend, Choudrant, LA 71227 Tyler4B G. Storms, 941 N. Trenton Street, Ruston, LA 71270-3327 FOURTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT (11 seats) Parishes of Morehouse & Ouachita Martin Shane Craighead, PO Box 4787, Monroe, LA 71211-4787 Dianne L. Hill, 1401 Hudson Lane, Suite 137, Monroe, LA 71201 Daniel J.