The Platinum/Palladium Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repoussé Work for Amateurs

rf Bi oN? ^ ^ iTION av op OCT i 3 f943 2 MAY 8 1933 DEC 3 1938 MAY 6 id i 28 dec j o m? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Public Library http://www.archive.org/details/repoussworkforamOOhasl GROUP OF LEAVES. Repousse Work for Amateurs. : REPOUSSE WORK FOR AMATEURS: BEING THE ART OF ORNAMENTING THIN METAL WITH RAISED FIGURES. tfjLd*- 6 By L. L. HASLOPE. ILLUSTRATED. LONDON L. UPCOTT GILL, 170, STRAND, W.C, 1887. PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, STRAND, LONDON. 3W PREFACE. " JjJjtfN these days, when of making books there is no end," ^*^ and every description of work, whether professional or amateur, has a literature of its own, it is strange that scarcely anything should have been written on the fascinating arts of Chasing and Repousse Work. It is true that a few articles have appeared in various periodicals on the subject, but with scarcely an exception they treated only of Working on Wood, and the directions given were generally crude and imperfect. This is the more surprising when we consider how fashionable Repousse Work has become of late years, both here and in America; indeed, in the latter country, "Do you pound brass ? " is said to be a very common question. I have written the following pages in the hope that they might, in some measure, supply a want, and prove of service to my brother amateurs. It has been hinted to me that some of my chapters are rather "advanced;" in other words, that I have gone farther than amateurs are likely to follow me. -

2019 Pricing Grid Numismatic Gold Platinum Palladium Liberty

2019 Pricing of Numismatic Gold, Commemorative Gold, Platinum, and Palladium Products **Does not reflect $5 discount during introductory period Average American Eagle American Eagle American Buffalo American Eagle American Eagle American Liberty Commemorative Gold Commemorative Gold Size Price per Ounce Gold Proof Gold Uncirculated 24K Gold Proof Platinum Proof Palladium Reverse Proof 24K Gold Proof* Uncirculated* $500.00 to $549.99 1 oz $877.50 $840.00 $910.00 $920.00 $937.50 $940.00 1/2 oz $455.00 1/4 oz $240.00 1/10 oz $107.50 $135.00 4-coin set $1,627.50 commemorative gold $240.00 $230.00 commemorative 3-coin set $305.50 $550.00 to $599.99 1 oz $927.50 $890.00 $960.00 $970.00 $987.50 $990.00 1/2 oz $480.00 1/4 oz $252.50 1/10 oz $112.50 $140.00 4-coin set $1,720.00 commemorative gold $252.25 $242.25 commemorative 3-coin set $317.75 $600.00 to $649.99 1 oz $977.50 $940.00 $1,010.00 $1,020.00 $1,037.50 $1,040.00 1/2 oz $505.00 1/4 oz $265.00 1/10 oz $117.50 $145.00 4-coin set $1,812.50 commemorative gold $264.50 $254.50 commemorative 3-coin set $330.00 $650.00 to $699.99 1 oz $1,027.50 $990.00 $1,060.00 $1,070.00 $1,087.50 $1,090.00 1/2 oz $530.00 1/4 oz $277.50 1/10 oz $122.50 $150.00 4-coin set $1,905.00 commemorative gold $276.75 $266.75 commemorative 3-coin set $342.25 $700.00 to $749.99 1 oz $1,077.50 $1,040.00 $1,110.00 $1,120.00 $1,137.50 $1,140.00 1/2 oz $555.00 1/4 oz $290.00 1/10 oz $127.50 $155.00 4-coin set $1,997.50 commemorative gold $289.00 $279.00 commemorative 3-coin set $354.50 $750.00 to $799.99 1 oz $1,127.50 $1,090.00 -

The Platinum Print: a Catalyst for Discussion

The Platinum Print: a catalyst for discussion Defined: distinguished by its matte finish and subtle tonal gradations image is embedded into the fibers of the paper non-silver process iron salts are used to sensitize paper prior to development Upon exposure to light, a faint image appears development process converts iron salts platinum faint image becomes more pronounced1 1. The History of the Platinum Print Due to the similar qualities and processes, The terms platinotype, palladium prints and platinum prints are often used interchangeably. According to James Reilly, the platinotype and the platinum print are in fact congruent photographic processes yielding in what would be the same photographic print. Having said that please refer to figure 1.1, below. This chart demonstrates not necessarily the date of invention or discovery of the most popular historic photographic processes, but rather the years in which the process was most dominantly used. 1 Figure 1.1 Chronology of the use of photographic processes in the United States. (up to 1984.) The chart indicates that platinum prints were popular for approximately 40 years from 1870s to the 1930s, competing with the well-established albumen prints and eventually being overtaken by the gelatin silver processes which came on the scene about the same time. A long string of inventors and their inventions led to the ultimate culmination in what became known as the platinum print, one of the few non-silver processes used in photography. In 1830, Ferdinand Gehlen noted that ultraviolet light would alter the color of platinum salts and cause the ferric salts to separate out into a ferrous state. -

Testing Gold Platinum Silver.Qxp

PROCEDURES FOR TESTING GOLD, PLATINUM AND SILVER To test for the karat value of gold, platinum and silver, you will need the following materials and tools: • Black acid testing stone that is washed thoroughly with water prior to each test. • Acids. • Gold testing needles with gold tips - used for comparison with test pieces. Testing for 10K, 12K, 14K Scratch the gold piece to be tested on the stone. Next to this position, scratch the appropriate needle (10, 12 or 14K). Place a drop of the appropriate acid on the stone where the gold was rubbed off. If the gold is the same karat or higher, the color of the scratch mark for the gold piece will appear the same as the mark from the needle. If that gold piece is a lower karat, the scratched deposit will become fainter and eventually disappear. Testing for 18K Scratch the test piece on the stone and apply 18K acid. Any gold that is less than 18K will disappear in less than 30 seconds. Gold that remains on the stone is 18K or higher. Testing for 20K and 24K Scratch the gold piece on the stone. Next, scratch any item of know karat (coin or needle) on the stone. Apply one drop of acid to area. The material that starts to disappear has the lower karat. Testing for Platinum Scratch the test item on the stone and apply one drop of acid to the application on the stone. If the material is platinum, it should keep its white, bright color. White Gold The same procedure for platinum can be used for 18K white gold. -

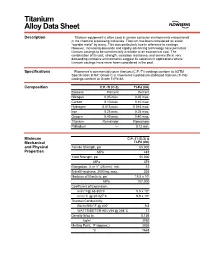

Titanium Alloy Data Sheet

M Titanium Alloy Data Sheet Description Titanium equipment is often used in severe corrosive environments encountered in the chemical processing industries. Titanium has been considered an exotic “wonder metal” by many. This was particularly true in reference to castings. However, increasing demands and rapidly advancing technology have permitted titanium castings to be commercially available at an economical cost. The combination of its cost, strength, corrosion resistance, and service life in very demanding corrosive environments suggest its selection in applications where titanium castings have never been considered in the past. Specifications Flowserve’s commercially pure titanium (C.P.-Ti) castings conform to ASTM Specification B367, Grade C-3. Flowserve’s palladium stabilized titanium (Ti-Pd) castings conform to Grade Ti-Pd 8A. Composition C.P.-Ti (C-3) Ti-Pd (8A) Element Percent Percent Nitrogen 0.05 max. 0.05 max. Carbon 0.10 max. 0.10 max. Hydrogen 0.015 max. 0.015 max. Iron 0.25 max. 0.25 max. Oxygen 0.40 max. 0.40 max. Titanium Remainder Remainder Palladium –– 0.12 min. Minimum C.P.-Ti (C-3) & Mechanical Ti-Pd (8A) and Physical Tensile Strength, psi 65,000 Properties MPa 448 Yield Strength, psi 55,000 MPa 379 Elongation, % in 1" (25 mm), min. 12 Brinell Hardness, 3000 kg, max. 235 Modulus of Elasticity, psi 15.5 x 106 MPa 107,000 Coefficient of Expansion, in/in/°F@ 68-800°F 5.5 x 10-6 m/m/°C @ 20-427°C 9.9 x 10-6 Thermal Conductivity, Btu/hr/ft/ft2/°F @ 400° 9.8 WATTS/METER-KELVIN @ 204°C 17 Density lb/cu in 0.136 kg/m3 3760 Melting Point, °F (approx.) 3035 °C 1668 Titanium Alloy Data Sheet (continued) Corrosion The outstanding mechanical and physical properties of titanium, combined with its Resistance unexpected corrosion resistance in many environments, makes it an excellent choice for particularly aggressive environments like wet chlorine, chlorine dioxide, sodium and calcium hypochlorite, chlorinated brines, chloride salt solutions, nitric acid, chromic acid, and hydrobromic acid. -

Nuances De Vie

NUANCES DE VIE: PHOTOGRAPHIC PRINTMAKING IN THREE MEDIUMS A Project Presented to the faculty of the Departments of Art and Design California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in SPECIAL MAJOR (Printmaking and Photography) by Valerie Wheeler SPRING 2012 © 2012 Valerie Wheeler ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii NUANCES DE VIE: PHOTOGRAPHIC PRINTMAKING IN THREE MEDIUMS A Project by Valerie Wheeler Approved by: ________________________________, Sponsor Sharmon Goff ________________________________, Committee Member Roger Vail ________________________________, Committee Member Nigel Poor _______________________ Date iii Student: Valerie Wheeler I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. ______________________________, Dean ________________ Chevelle Newsome, Ph.D. Date Office of Graduate Studies iv Abstract of NUANCES DE VIE: PHOTOGRAPHIC PRINTMAKING IN THREE MEDIUMS by Valerie Wheeler The goal of this special major in printmaking and photography was to bridge the two art forms through photo etching using classical and modern methods. In the process of learning large format photography, intaglio printmaking (photogravure), and non-etch intagliotype printing, I expanded the project to include platinum and palladium printing (making platinotypes and platino-palladiotypes). The continuity among the mediums rested upon the images, a few of which were printed in more than one medium. Landscapes, floral still-lifes, architecture, and a few portraits came together in a body of complementary work consisting of fifty-two images in four sizes. The thesis exhibition was installed and open for a week in the Robert Else Gallery; it included short technical labels to explain the three mediums. -

Advertising Platinum Jewelry

FTC FACTS for Business Advertising Platinum Jewelry ftc.gov The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC’s) Jewelry Guides describe how to accurately mark and advertise the platinum content of the jewelry you market or sell. Platinum jewelry can be alloyed with other metals: either precious platinum group metals (PGMs) — iridium, palladium, ruthenium, rhodium, and osmium — or non-precious base metals like copper and cobalt. In recent years, manufacturers have alloyed some platinum jewelry with a larger percentage of base metals. Recent revisions to the FTC’s Jewelry Guides address the marking of jewelry made of platinum and non-precious metal alloys and when disclosures are appropriate. When Disclosures Should Be Made Product descriptions should not be misleading, and they should disclose material information to jewelry buyers. If the platinum/base metal-alloyed item you are selling does not have the properties of products that are almost pure platinum or have a very high percentage of platinum, you should disclose that to prospective buyers. They may want to know about the value of the product as well as its durability, luster, density, scratch resistance, tarnish resistance, its ability to be resized or repaired, how well it retains precious metal over time, and whether it’s hypoallergenic. You may claim your product has these properties only if you have competent and reliable scientific evidence that your product — that has been alloyed with 15 to 50 percent non-precious or base metals — doesn’t differ in a material way from a product that is 85 percent or more pure platinum. Facts for Business Terms Used in Advertising • Jewelry that has 850 parts per thousand pure platinum — meaning that it is 85 percent pure • Any item that is less than 500 parts per platinum and 15 percent other metals — may be thousand pure platinum should not be marked referred to as “traditional platinum.” The other or described as platinum even if you modify the metals can include either PGMs or non-precious term by adding the piece’s platinum content in base metals. -

THE USE of MIXED MEDIA in the PRODUCTION of METAL ART by Mensah, Emmanuel (B.A. Industrial Art, Metals)

THE USE OF MIXED MEDIA IN THE PRODUCTION OF METAL ART By Mensah, Emmanuel (B.A. Industrial Art, Metals) A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS (ART EDUCATION) Faculty of Art, College of Art and Social Sciences March 2011 © 2011, Department of General Art Studies DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work toward the M.A Art Education degree and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no materials previously published by another person or material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the university, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. ……………………………….. ……………………………….. ………………………….. Student’s name & ID Signature Date Certified by ……………………………….. ……………………………….. ………………………….. Supervisor’s Name Signature Date Certified by ……………………………….. ……………………………….. ………………………….. Head of Department’s Name Signature Date ii ABSTRACT The focus of this study was to explore and incorporate various artistic and non artistic media into the production of metal art. The researcher was particularly interested in integrating more non metallic materials that are not traditional to the production of metal art in the decoration, finishing and the protective coating of metal art works. Basic hand forming techniques including raising, chasing and repoussé, piercing and soldering were employed in the execution of the works. Other techniques such as painting, dyeing and macramé were also used. Non metallic media that were used in the production of the works included leather, nail polish, acrylic paint, epoxy, formica glue, graphite, eye pencil, lagging, foam, wood, shoe polish, shoe lace, eggshell paper, spray paint, cotton cords and correction fluid. -

The Platinum Print B the History of the Platinum Process

THE PLATINUM PRINT B THE HISTORY OF THE PLATINUM PROCESS A REFERENCE TO THE SCIENTIFIC, COMMERCIAL, AND AESTHETIC DEVELOPMENT OF THE PLATINOTYPE JOHN HAFEY & TOM SHILLEA The Platinum Print by John Hafey and Tom Shillea ISBN 0-89938-000-X Copyright 1979 Graphic Arts Research Center Rochester Insitute of Technology This Adobe Acrobat document produced in november 2002 is based on the illustrated primer The Platinum Print written by John Hafey and Tom Shillea. It is about an exhibition called „The Contemporary Platinotype“ which took place at Rochester Institute of Technology in 1979. Unfortunately, that illustrated primer is now out of print. But the PDF-Version contains both the original text about the scientific discovery, the commercial developement and the aesthetic evolution of the Platinotype. It is requested to make use of this document for scientific research or pure information only! If any person may be offended because of misuse of copyright laws, please contact me at [email protected] Frank Rossi, 2002 Scientific Discovery and Commercial Development Ferdinand Gehlen was the first person to explore the action and effects of light rays upon platinum and record his experiments. In 1830, he discovered that a solution of platinum chloride when exposed to light, first turned a yellow color, and eventually formed a precipitate of metallic platinum.1 In 1831, experiments by the chemist Johann Wolfgang Dobereiner obtained important results. Born in Bavaria in 1780, he practiced pharmacy in Karlsruhe, and devoted himself to the study of the natural sciences, particularly chemistry. In 1810, he was given the position of professor of chemistry and pharmacy at the University of Jena, where he taught until his death in 1849.2 He observed that platinum metal was only slightly affected by the action of light, and concluded that some substance would have to be added to the pure platinum metal to in- crease its sensitivity to light. -

JD: Jewelry Design

JD: Jewelry Design JD 101 — Introduction to Jewelry JD 115 — Metal Forming Techniques: Fabrication Chasing and Repousse 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours 1.5 credits; 3 lab hours Basic processes used in the design and Introduces students to jewelry-forming creation of jewelry. Students fabricate their techniques by making their own dapping own designs in the studio. and chasing tools by means of forging, JD 102 — Enameling Techniques for annealing, and tempering. Using these Precious Metals/Fine Jewelry/Objects tools, objects are created by repousse and D'Art other methods. 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours Prerequisite(s): all first-semester Jewelry Vitreous enameling on precious metals. Design courses or approval of chairperson Studies include an emphasis on the "Co-requisite(s): JD 116, JD 122, JD metallurgical properties of gold, silver, and 134, JD 171, and JD 173 or approval of platinum and their chemical compatibility chairperson. with enamels. Surface treatments, ancient JD 117 — Enameling for Contemporary and modern, that intensify the jewel- Jewelry like qualities of vitreous enamel on 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours precious metal will be explored. along with Vitreous enamel has been used for construction techniques that help students centuries as a means of adding color transform glass into beautiful, functional and richness to precious objects and jewelry and objects of art. jewelry. This course examines historical Prerequisite(s): JD 101. and contemporary uses of enamel, and JD 103 — Jewelry and Accessories explores the various methods of its Fabrication (Interdisciplinary) application, including cloisonne, limoges 2 credits; 1 lecture and 2 lab hours and champleve, the use of silver and gold This is an interdisciplinary course cross- foils, oxidation, surface finishing and setting listed with LD 103. -

Platinum, Silver- Platinum, and Palladium Prints

Noble Metals for the Early Modern Era: Platinum, Silver- Platinum, and Palladium Prints Constance Mc Cabe Histories of photography usually emphasize the photogra- phers’ command of the camera and the resulting pictures while offering little insight into the extensive chemical and technical artistry performed in studios and darkrooms. Research into the materials and methods behind photo- graphic prints, however, can shed light on the aesthetic goals of the photographers and help to determine which properties are the result of artistic decisions and which might be the natural effects of aging. By studying the array of platinum, silver- platinum, and palladium prints in the Thomas Walther Collection, we are given an opportunity to appreciate how photographers in the early twentieth cen- tury manipulated materials and chemicals to achieve a quasi-modern aesthetic. The aesthetic benchmark for many photographers at the dawn of the twentieth century was the platinum print, extolled for its unparalleled artistic qualities and perma- nence. Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and Clarence H. White (1871–1925), both highly influential photographers and lead- ers of Pictorialism, a movement championing photography as fine art, praised platinum as the ideal photographic medium for their exhibition prints. Their disciples contin- ued to test the medium for new and unusual effects, exploiting such curiosities as multiple exposures, tone reversal, and solarization, and exploring unconventional compositional elements and abstraction. Highly attuned to the technical craft of their work, they investigated myriad products and chemical modifications to achieve their artistic fig. 1 Alfred Stieglitz. From the Back Window at “291”. April 3, 1915. Platinum print, objectives. -

Gemstones by Donald W

GEMSTONES By Donald W. olson Domestic survey data and tables were prepared by Nicholas A. Muniz, statistical assistant, and the world production table was prepared by Glenn J. Wallace, international data coordinator. In this report, the terms “gem” and “gemstone” mean any gemstones and on the cutting and polishing of large diamond mineral or organic material (such as amber, pearl, petrified wood, stones. Industry employment is estimated to range from 1,000 to and shell) used for personal adornment, display, or object of art ,500 workers (U.S. International Trade Commission, 1997, p. 1). because it possesses beauty, durability, and rarity. Of more than Most natural gemstone producers in the United states 4,000 mineral species, only about 100 possess all these attributes and are small businesses that are widely dispersed and operate are considered to be gemstones. Silicates other than quartz are the independently. the small producers probably have an average largest group of gemstones; oxides and quartz are the second largest of less than three employees, including those who only work (table 1). Gemstones are subdivided into diamond and colored part time. the number of gemstone mines operating from gemstones, which in this report designates all natural nondiamond year to year fluctuates because the uncertainty associated with gems. In addition, laboratory-created gemstones, cultured pearls, the discovery and marketing of gem-quality minerals makes and gemstone simulants are discussed but are treated separately it difficult to obtain financing for developing and sustaining from natural gemstones (table 2). Trade data in this report are economically viable deposits (U.S.