Wagneriana June–July 2006 Wer Weiß Was Ich Thu’! Volume 3, Number 3 – Das Rheingold from the Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

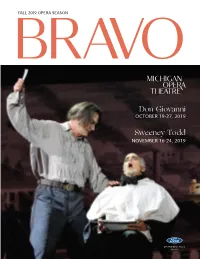

Don Giovanni Sweeney Todd

FALL 2019 OPERA SEASON B R AVO Don Giovanni OCTOBER 19-27, 2019 Sweeney Todd NOVEMBER 16-24, 2019 2019 Fall Opera Season Sponsor e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. Choose one from each course: FIRST COURSE Caesar Side Salad Chef’s Soup of the Day e Whitney Duet MAIN COURSE Grilled Lamb Chops Lake Superior White sh Pan Roasted “Brick” Chicken Sautéed Gnocchi View current menus DESSERT and reserve online at Chocolate Mousse or www.thewhitney.com Mixed Berry Sorbet with Fresh Berries or call 313-832-5700 $39.95 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit e Katherine McGregor Dessert Parlor …at e Whitney. Named a er David Whitney’s daughter, Katherine Whitney McGregor, our intimate dessert parlor on the Mansion’s third oor features a variety of decadent cakes, tortes, and miniature desserts. e menu also includes chef-prepared specialties, pies, and “Drinkable Desserts.” Don’t miss the amazing aming dessert station featuring Bananas Foster and Cherries Jubilee. Reserve tonight’s table online at www.thewhitney.com or call 313-832-5700 4421 Woodward Ave., Detroit Pre- eater Menu Available on performance date with today’s ticket. -

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Time 1925 1930 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010

Giulio Gatti Casazza 1926 Director, Metropolitan Opera Arturo Toscanini Leopold Stokowski 1926 1930 Conductor Conductor Pietro Mascagni Lucrezia Bori James Cæsar Petrillo 1926 1930 1948 Composer Singer Head, American Federation of Musicians Richard Strauss Alfred Hertz Sergei Koussevitsky Helen Traubel Charles Munch 1938 1927 1930 1946 1949 Composer and conductor Conductor Conductor Singer Conductor Ignace J Paderewski Geraldine Farrar Joseph Deems Taylor Marian Anderson Cole Porter 1939 1927 1931 1946 1949 Kirsten Flagstad Pianist, politician Singer Composer, critic Singer Composer 1935 Lauritz Melchior Giulio Gatti-Casazza Ignace Jan Paderewski Yehudi Menuhin Singer Artur Rodziński Gian Carlo Menotti Maria Callas 1940 1923 1928 1932 1947 1950 1956 Artur Rubinstein Edward Johnson Singer Director, Metropolitan Opera Pianist, politician Violinist; 16 years old Conductor Composer Singer 1966 1936 Leopold Stokowski Pianist Johann Sebastian Bach Nellie Melba Mary Garden Lawrence Tibbett Singer Arturo Toscanini Mario Lanza & Enrico Caruso Leonard Bernstein 1940 1968 1927 1930 1933 1948 1951 1957 Jean Sibelius Conductor Dmitri Shostakovich Composer (1685–1750) Singer Singer Singer Conductor Singers Composer, conductor 1937 1942 Beverly Sills Richard Strauss Rosa Ponselle Arturo Toscanini Composer Composer Benjamin Britten Patrice Munsel Renata Tebaldi Rudolf Bing Luciano Pavarotti 1971 1927 1931 1934 1948 1951 1958 1966 1979 Sergei Koussevitsky Sir Thomas Beecham Leontyne Price Singer Georg Solti Composer, conductor Singer Conductor Composer -

Cast Amendment Die Zauberflote

27 FEBRUARY 2015 CAST AMENDMENT DIE ZAUBERFLOTE (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart) 28 February; 2, 4, 6, 7, 9 and 11 March Due to personal reasons, Australian tenor and Jette Parker Young Artist Samuel Sakker has withdrawn from singing the role of First Man in Armour. The role will now be sung by British tenor and member of the Royal Opera Chorus Andrew Macnair . Andrew Macnair joined the Royal Opera Chorus in 2006. His solo roles for The Royal Opera have included Drunken Guest ( Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk), Notary ( Il barbiere di Siviglia ), Echo ( The Tsarina's Slippers ) and Don Curzio ( Le nozze di Figaro ). The rest of the cast remains unchanged, with British tenor Toby Spence (2, 6, 9, 11 Mar) and Slovakian tenor Pavol Breslik (28 Feb; 4, 7 March) sharing the role of Tamino, American soprano Janai Brugger (2, 6, 9, 11 Mar) and German soprano Christiane Karg (28 Feb; 4, 7 March ) sharing the role of Pamina, Welsh soprano Rhian Lois (28 Feb; 2, 4, 6 Mar) and Australian soprano and Jette Parker Young Artist Lauren Fagan ( 7, 9, 11 Mar) sharing the role of Papagena, Polish soprano Anna Siminska as Queen of the Night, Austrian baritone Markus Werba as Papageno, German bass Georg Zeppenfeld as Sarastro, British tenor Colin Judson as Monostatos, British baritone Benjamin Bevan (2, 6, 9, 11 Mar) and British bass Robert Lloyd (28 Feb; 4, 7 March) sharing the role of the Speaker of the Temple, Irish soprano Sinéad Mulhern, Russian mezzo-soprano and Jette Parker Young Artist Nadezhda Karyazina and British contralto Claudia Huckle as the Three Ladies , Scottish tenor Harry Nicoll and Scottish baritone Donald Maxwell as First and Second Priest and British bass and Jette Parker Young Artist James Platt as Second Man in Armour. -

January 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 01 (January 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/199 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7 A . " f ft.S. &. ft. P. deed not Ucende Some Recent Additions Select Your Choruses conceit cuid.iccitzt fotidt&{ to the Catalog of Oliver Ditson Co. NOW PIANO SOLOS—SHEET MUSIC The wide variety of selections listed below, and the complete AND PUBLISHERS in the THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS, AUTHORS BMI catalogue of choruses, are especially noted as compo- MYRA ADLER Grade Pr. MAUDE LAFFERTY sitions frequently used by so many nationally famous edu- payment of the performing fee. Christmas Candles .3-4 $0.40 The Ball in the Fountain 4 .40 correspondence below reaffirms its traditional stand regarding ?-3 Happy Summer Day .40 VERNON LANE cators in their Festival Events, Clinics and regular programs. BERENICE BENSON BENTLEY Mexican Poppies 3 .35 The Witching Hour .2-3 .30 CEDRIC W. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV With onstage guests directors Brian Large and Jonathan Miller & former BBC Head of Music & Arts Humphrey Burton on Wednesday 30 April BFI Southbank’s annual Broadcasting the Arts strand will this year examine Opera on TV; featuring the talents of Maria Callas and Lesley Garrett, and titles such as Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) and The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), this season will show how television helped to democratise this art form, bringing Opera into homes across the UK and in the process increasing the public’s understanding and appreciation. In the past, television has covered opera in essentially four ways: the live and recorded outside broadcast of a pre-existing operatic production; the adaptation of well-known classical opera for remounting in the TV studio or on location; the very rare commission of operas specifically for television; and the immense contribution from a host of arts documentaries about the world of opera production and the operatic stars that are the motor of the industry. Examples of these different approaches which will be screened in the season range from the David Hockney-designed The Magic Flute (Southern TV/Glyndebourne, 1978) and Luchino Visconti’s stage direction of Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) to Peter Brook’s critically acclaimed filmed version of The Tragedy of Carmen (Alby Films/CH4, 1983), Jonathan Miller’s The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), starring Lesley Garret and Eric Idle, and ENO’s TV studio remounting of Handel’s Julius Caesar with Dame Janet Baker. Documentaries will round out the experience with a focus on the legendary Maria Callas, featuring rare archive material, and an episode of Monitor with John Schlesinger’s look at an Italian Opera Company (BBC, 1958). -

MONDAY 1 OCTOBER 2018 CAST AMENDMENT GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG (Richard Wagner) Monday 1 October 2018 at 4Pm

MONDAY 1 OCTOBER 2018 CAST AMENDMENT GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG (Richard Wagner) Monday 1 October 2018 at 4pm Due to the indisposition of Christina Bock, Rachael Lloyd sings Wellgunde in today’s performance. Rachael Lloyd has sung Alisa (Lucia di Lammermoor) and Kate Pinkerton (Madama Butterfly) for The Royal Opera. Other appearances include Mrs Anderssen in Sondheim’s A Little Night Music (Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris), the title role of Carmen (Raymond Gubbay Ltd at Royal Albert Hall), Miss Jessel in The Turn of the Screw, Third Lady in The Magic Flute and Pitti-Sing in The Mikado (ENO), Amastris in Xerxes (ETO, Early Opera Company), Maddalena in Rigoletto (Iford Arts), Aristea in L’Olimpiade (Buxton Festival), Meg Page in Falstaff (Glyndebourne on Tour), Woman/Mother in Dove’s The Day After (ENO Baylis) and Cornelia in Giulio Cesare (Glyndebourne Festival). Notable concert performances include Rossini’s Stabat Mater (Ulster Orchestra), Dido and Aeneas (Spitalfields Festival), Messiah (Kristiansund), Ravel’s Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé (LPO) andSchumann’s Frauenliebe und - leben and Elgar’s Sea Pictures (Opéra de Lille). Plans include Selene in Berenice (Royal Opera). The rest of the cast remains the same with German tenor Stefan Vinke as Siegfried, Swedish soprano Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde, Austrian baritone Markus Butter as Gunther, Danish bass Stephen Milling as Hagen, American soprano Emily Magee as Gutrune, Scottish mezzo-soprano Karen Cargill as Waltraute, German baritone Johannes Martin Kränzle as Alberich, British contralto Claudia Huckle as First Norn, For all Royal Opera House press releases visit www.roh.org.uk/press German soprano Irmgard Wilsmaier as Second Norn, Norwegian soprano Lise Davidsen as Third Norn, Australian soprano Lauren Fagan as Woglinde and English mezzo-soprano Angela Simkin as Flosshilde, conducted by Antonio Pappano. -

Elisa Citterio Discography 2009 Handel Between Heaven and Earth

Elisa Citterio Discography 2009 Handel Between Heaven And Earth CD Stefano Montanari, conductor Accademia Bizantina Soloists Sandrine Piau,Topi Lehtipuu 2008 Handel The Musick For The Royal Fireworks, Concerti A Due Cori CD Alfredo Bernardini Zefiro Fiorenza Concerti & Sonate CD Stefano Demicheli Dolce & Tempesta 2003 Various Storia Del Sonar A Quattro - Volume III CD Joseph Joachim Quartet 2001 Schuster 6 Quartetti Padovani CD Joseph Joachim Quartet 2000 Vivaldi La Tempesta di Mare CD Fabio Biondi Europa Galante 1998 Monteverdi Settimo Libro Dei Madrigali CD Claudio Cavina La Venexiana Recordings with L’orchestra del Teatro alla Scala di Milano 2015 Mozart Don Giovanni DVD Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Peter Mattei, Bryn Terfel, Anna Netrebko, Barbara Frittoli, Giuseppe Filianoti, Anna Prohaska 2014 Jarre Notre-Dame De Paris DVD Paul Connelly, conductor Ballet Company & Orchestra of Teatro alla Scala Natalia Osipova, Roberto Bolle, Mick Zeni, Eris Nezha Wagner Goetterdammerung DVD Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Maria Gortsevskaya, Lance Ryan, Iréne Theorin, Mikhail Petrenko Wagner Siegfried DVD Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Lance Ryan, Peter Bronder, Terje Stensvold, Johannes Martin Kränzle, Alexander Tsymbalyuk, Anna Larsson, Nina Stemme, Rinnat Moriah Beethoven Fidelio VC Daniel Barenboim, conductor Orchestra & Chorus of Teatro alla Scala Peter Mattei, Falk Struckmann, Klaus Florian Vogt, Jonas Kaufmann, Anja Kampe, Kwangchul -

Meistersinger Von Nürnberg

RICHARD WAGNERʼS DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG Links to resources and lesson plans related to Wagnerʼs opera, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Classical Net http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/wagner.php Includes biographical information about Richard Wagner. Dartmouth: “Under the Linden Tree” by Walter von der Vogelweide (1168-1228) http://www.dartmouth.edu/~german/German9/Vogelweide.html Original text in Middle High German, with translations into modern German and English. Glyndebourne: An Introduction to Wagnerʼs Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tXPY-4SMp1w To accompany the first ever Glyndebourne production of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (the long held dream of the founder John Christie) Professor Julian Johnson of London Holloway University gives us some studied insights into the work. Glyndebourne: Scale and Detail Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg https://vimeo.com/24310185 Get a glimpse into putting on this epic scale Opera from Director David McVicar, Designer Vicki Mortimer, Lighting designer Paule Constable, and movement director Andrew George. Backstage and rehearsal footage recorded at Glyndebourne in May 2011. Great Performances: Fast Facts, Long Opera http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/gp-met-die-meistersinger-von-nurnberg-fast-facts-long-opera/3951/ Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (“The Master-Singer of Nuremberg”) received its first Great Performances at the Met broadcast in 2014. The Guardian: Die Meistersinger: 'It's Wagner's most heartwarming opera' http://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/may/19/die-meistersinger-von-nurnberg-glyndebourne Director David McVicar on "looking Meistersinger squarely in the face and recognising the dark undercurrents which are barely beneath the surface." "When Wagner composed the opera in the 1860s, he thought he was telling a joyous human story," he says. -

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021

2021 WFMT Opera Series Broadcast Schedule & Cast Information —Spring/Summer 2021 Please Note: due to production considerations, duration for each production is subject to change. Please consult associated cue sheet for final cast list, timings, and more details. Please contact [email protected] for more information. PROGRAM #: OS 21-01 RELEASE: June 12, 2021 OPERA: Handel Double-Bill: Acis and Galatea & Apollo e Dafne COMPOSER: George Frideric Handel LIBRETTO: John Gay (Acis and Galatea) G.F. Handel (Apollo e Dafne) PRESENTING COMPANY: Haymarket Opera Company CAST: Acis and Galatea Acis Michael St. Peter Galatea Kimberly Jones Polyphemus David Govertsen Damon Kaitlin Foley Chorus Kaitlin Foley, Mallory Harding, Ryan Townsend Strand, Jianghai Ho, Dorian McCall CAST: Apollo e Dafne Apollo Ryan de Ryke Dafne Erica Schuller ENSEMBLE: Haymarket Ensemble CONDUCTOR: Craig Trompeter CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Chase Hopkins FILM DIRECTOR: Garry Grasinski LIGHTING DESIGNER: Lindsey Lyddan AUDIO ENGINEER: Mary Mazurek COVID COMPLIANCE OFFICER: Kait Samuels ORIGINAL ART: Zuleyka V. Benitez Approx. Length: 2 hours, 48 minutes PROGRAM #: OS 21-02 RELEASE: June 19, 2021 OPERA: Tosca (in Italian) COMPOSER: Giacomo Puccini LIBRETTO: Luigi Illica & Giuseppe Giacosa VENUE: Royal Opera House PRESENTING COMPANY: Royal Opera CAST: Tosca Angela Gheorghiu Cavaradossi Jonas Kaufmann Scarpia Sir Bryn Terfel Spoletta Hubert Francis Angelotti Lukas Jakobski Sacristan Jeremy White Sciarrone Zheng Zhou Shepherd Boy William Payne ENSEMBLE: Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, -

Riccardo Muti Conductor Michele Campanella Piano Eric Cutler Tenor Men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe Director Wagne

Program ONE huNdrEd TwENTy-FirST SEASON Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Friday, September 30, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, October 1, 2011, at 8:00 Tuesday, October 4, 2011, at 7:30 riccardo muti conductor michele Campanella piano Eric Cutler tenor men of the Chicago Symphony Chorus Duain Wolfe director Wagner Huldigungsmarsch Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major Allegro maestoso Quasi adagio— Allegretto vivace— Allegro marziale animato MiChElE CampanellA IntErmISSIon Liszt A Faust Symphony Faust: lento assai—Allegro impetuoso Gretchen: Andante soave Mephistopheles: Allegro vivace, ironico EriC CuTlEr MEN OF ThE Chicago SyMPhONy ChOruS This concert series is generously made possible by Mr. & Mrs. Dietrich M. Gross. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks Mr. & Mrs. John Giura for their leadership support in partially sponsoring Friday evening’s performance. CSO Tuesday series concerts are sponsored by United Airlines. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PhilliP huSChEr ne hundred years ago, the Chicago Symphony paid tribute Oto the centenary of the birth of Franz Liszt with the pro- gram of music Riccardo Muti conducts this week to honor the bicentennial of the composer’s birth. Today, Liszt’s stature in the music world seems diminished—his music is not all that regularly performed, aside from a few works, such as the B minor piano sonata, that have never gone out of favor; and he is more a name in the history books than an indispensable part of our concert life.