15.12.2018 Final Print UGC Project Sebak Jana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seat Matrix JELET-2020.Xlsx Page 1 of 33 Seat Matrix, JELET-2020 Counselling

Seat Matrix, JELET-2020 Counselling Institute Name Branch Name OPNO OPPH BANO BAPH BBNO BBPH SCNO SCPH STNO STPH Total Cooch Behar Government Civil Engineering 9 1 2 0 1 0 4 0 1 018 Engineering College, Cooch Behar Cooch Behar Government Computer Science & 5 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 010 Engineering College, Cooch Behar Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology Cooch Behar Government Electronics & Communication 8 0 1 1 1 0 3 0 1 015 Engineering College, Cooch Behar Engineering/Electronics & Telecommunication Engineering Cooch Behar Government Electrical Engineering 10 1 2 0 1 0 5 0 1 0 20 Engineering College, Cooch Behar Cooch Behar Government Mechanical Engineering 11 1 2 0 2 0 5 0 1 0 22 Engineering College, Cooch Behar Goverment College of Engineering Computer Science & 11 1 2 0 2 0 5 0 1 0 22 and Leather Technology, Kolkata Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology Goverment College of Engineering Information Technology 5 0 1 0 1 0 2 0 1 010 and Leather Technology, Kolkata Goverment College of Engineering Leather Technology 8 1 2 0 1 0 4 0 1 017 and Leather Technology, Kolkata Govt. College of Engg. & Textile Computer Science & 11 Technology, Berhampore Engineering/ Computer Science 6 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 & Technology Govt. College of Engg. & Textile Electrical Engineering 6 Technology, Berhampore 3 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 Govt. College of Engg. & Textile Mechanical Engineering 10 Technology, Berhampore 5 0 1 0 1 0 2 0 1 0 Govt. College of Engg. & Textile Textile Technology 14 Technology, Berhampore 7 1 1 0 1 0 2 1 1 0 Govt. -

West Bengal & Education Systems

IInternatiionall Journall of Computer Sciience & Communiicatiion (IISSN:: 0973-7391) Vollume 9 • IIssue 2 pp.. 5-8 March 2018 - Sept 2018 www.csjjournalls.com West Bengal & Education Systems: The Need and Initiatives of Cloud Based Education Systems Jayati Lahiri (Dey), Ashoke Das Department of Computer and Information Science, Raiganj University, Raiganj, West Bengal-733 134, India [email protected] Abstract: If the history of development of Indian education structure is studied minutely then it is found that education in West Bengal has played a vital role there. Educational environment of West Bengal was very rich from past days. Ram Mohan Roy, David Hare, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Shashi Bhusan Chatterjee, William Carey and many others educationist and social reformers the pillars of bring new age of revolution called renaissance in the Indian History. According to current census report West Bengal has got a literacy rate of 77.9%.Now-a- days technology plays a pivotal role in education system. Through different learning management system student gets immense opportunities to access vast field of resources of their need. In the field of education, cloud computing has its use in the field of education for a number of reasons. This computing technology will enable a numerous educational institution to use of the global internet resources for data management issues like data analysis and data storage. Through this paper the need for cloud computing in the field of education in West Bengal perspective has been pointed out in a very simple way. Keywords: West Bengal, Higher Education, Cloud Computing, Virtualization. 1. INTRODUCTION in the field of Higher Education. -

Education Policy in West Bengal

Education Policy In West Bengal meekly.Sometimes How uncomfortable lax is Francis Daviswhen misappropriateswiggly and infusive her Simone ranking avoidunknightly, some butpolemarch? bistred Boris mothers illegally or hypostatised soaringly. Rad overcome Boys dropped and development of hindu state govemment has been prescribed time, varshiki and west in urban areas contract teachers and secondary schools The policy research methodology will be? How effectively utilize kyan has been set up to west bengal indicate that would support in education policy west bengal? Huq was not in west in bengal education policy, which were zamindars as a perfect crime reporter in. To achieve gender norms and. After a voluntary organisations were built by employing ict. The new leaders dominated western sciences are often takes drugs? Textbooks were dedicated to icse and. Candidates each other. This chapter will help many of education policy? Maulvi syed ahmed also seek different legislative framework. This background to wash their islamic culture of schools but hindus for studies will be cleared without persian. West bengal government wanted muslim. Muslim inspectors are involved with parents, private schools has not really sufficient progress as fazlul huq was highest academic year plan period financial. There is of west bengal proposed by hindu consciousness among muslims education policy in west bengal and. Initially muslim students from lower classes with other stationeries, by japanese bombs followed. As to maintain their capability enhancement with an urgent issue as fees, separate nation one primary level for? Prime objective of policies were not enrolled into limelight once all. The policies were still taken into professional training facility to continue securing grants. -

A Study to Identify the Adoption Intention of PEN Card Amongst Diverse Groups

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878,Volume-8, Issue- 1C2, May 2019 A Study to Identify the Adoption Intention of PEN Card amongst Diverse Groups Rahul Kumar Ghosh, Anirban Das, Samir Kumar Bandyopadhyay ABSTRACT--- In India, the use of information technology in It is recommended that while India has a rousing vision of the private sector is a reality in all areas. However, in terms of where E – Governance is going there is a gap between public governance, India has been operating very slowly. The benefit conveyance and reality in the nation. The challenge population is not yet sufficiently developed and the infrastructure of E – Governance in India lies in giving the service to is not up to date. Under these circumstances, providing public services to the general population is extremely difficult. A general around a billion people [20]. While half of the nation is perceptual Intention to Adopt (IA) model and a technological getting up to speed, quick advance is being deferred because framework have been developed in advance to support the IA of operational, monetary, work force, arranging and usage model through Permanent Education Number (PEN) card to issues. The fundamental basic purpose behind these issues propose the electronic credential system in Indian education has been recognized as an over accentuation on putting system. However, the differences in the intention to adopt the resources into equipment and too little accentuation on PEN card were not measured. Therefore, this study was conducted to measure the differences in intention for adoption of creating programming and administrations [30]. -

West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000

r Department of School Education A Government of West Bengal Bikash Bidhan Nagar, Calc Antiual Report 1999-2000 Department of School Education Government of West Bengal Bikash Bhavan Bidhan Nagar, Calcutta-700 091 \amtuu of B4u«tcioQ«t PiittQiai «a4 A4niMttriti«o. ll^ ii Sri A«ir»kBdo M«rg, ! X a n i i C S i s w a s Minister-in-charge DEPT. OF EDUCATION (PRIMARY, SECONDARY AND MADRASAH) & DEPT. OF REFUGEE RELIEF AND REHABILITATION Government of West Bengal Dated, Calcutta 28.6.2000 FOREWORD It is a matter of satisfaction to me that 4th Annual Report of the Department of School Education, Government of West Bengal is being presented to all concerned who are interested to know the facts and figures of the system and achievements of the Department. The deficiencies which were revealed in the last 3 successive reports have been tried to be overcome in this report. The figures in relation to all sectors of School Education Department have been updated. All sorts of efforts have been taken in preparation of this Annual Report sO that the report may be all embracing in respect of various information of this Department. All the facts and figures in respect of achievement of Primary Education including the District Primary Education Programme have been incorporated in this Report. The position of Secondary School have been clearly adumbrated in this issue. At the same time, a large number of X-class High Schools which have been upgraded to Higher Secondary Schools (XI-XII) have also been mentioned in this Report. -

(EDCN) in West Bengal Date and Venue : 23.04.2018, IIM Kolkata

One Day Workshop on Entrepreneurship Development Centre Network (EDCN) in West Bengal Date and Venue : 23.04.2018, IIM Kolkata, Joka Organizer : MSME & Textiles, Government of West Bengal in collaboration with IIM innovation park Motivations : Government of West Bengal’s Startup Policy focuses on creating a strong startup ecosystem to nurture innovative entrepreneurial ideas and promote entrepreneurial spirit among younger generation, especially students. In pursuit of this, they had urged to set up Entrepreneurship Development Centre (EDC) in each Institution to encourage ideation and promote entrepreneurial awareness. An Entrepreneurship Development Centres Network (EDCN) has been created under the West Bengal Startup Policy to support various individual EDCs through cross learning, capacity building and handholding. IIM Calcutta Innovation Park (IIMCIP), being the Knowledge Partner, is the Coordinator of EDCN. It extends support to all EDC’s in capacity building, mentoring & networking, propelling cross pollination of ideas and mutual learning. A day-long workshop has been organized by Department of MSME & Textiles and IIMCIP on 23 April, 2018 from 11am - 4pm atIIMCIP, IIM Calcutta Campus, Diamond Harbour road, Joka, Kolkata – 700 104. Agenda Understanding role of EDCs, current state and challenges ahead. Preparation of plans on formation / strengthening of EDC’s appropriate to the institution. Gaps identification for capacity building, mentoring & networking. Annual calendar development. Participation from Jadavpur University : 1. Prof. Samiran Chattopadhyay 2. Dr. Sayan Chatterjee MINUTES OF THE MEETING Date: The 23rd of April, 2018 Location: TATA HALL, IIM Calcutta Resource persons : 1. Dr.SubhranshuSanyal: CEO - IIM Calcutta Innovation Park. 2. Mr.SumanMukhopadhyay: Director of banglanatak dot com, a social enterprise and Consultant adviser to the Department of MSME&T, GoWBon developing an entrepreneurial Eco-system in the state. -

Seat Matrix WBJEE-2021 for Website.Xlsx

Seat Marix WBJEE-2021 Sl. No. Institution Course OP OP- OA OA- OB OB- SC SC- ST ST- TFW JEE(M) Total PH PH PH PH PH 1 GHANI KHAN CHOUDHURY INSTITUTE OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 15 1 3 0 2 0 5 0 1 0 2 27 56 ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, MALDA 2 GHANI KHAN CHOUDHURY INSTITUTE OF FOOD TECHNOLOGY 15 0 3 0 1 0 6 1 2 0 2 26 56 ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, MALDA 3 GHANI KHAN CHOUDHURY INSTITUTE OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 15 1 2 0 2 0 5 0 2 0 2 27 56 ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY, MALDA 4 ABACUS INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING CIVIL ENGINEERING 48 0 1 0 0 0 3 0 2 0 0 6 60 & MANAGEMENT, MOGRA, HOOGHLY 5 ABACUS INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING COMPUTER SCIENCE & ENGINEERING 48 0 1 0 0 0 3 0 2 0 0 6 60 & MANAGEMENT, MOGRA, HOOGHLY 6 ABACUS INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 48 0 1 0 0 0 3 0 2 0 0 6 60 & MANAGEMENT, MOGRA, HOOGHLY 7 ABACUS INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION 48 0 1 0 0 0 3 0 2 0 0 6 60 & MANAGEMENT, MOGRA, HOOGHLY ENGINEERING/ELECTRONICS & TELECOMMUNICATION ENGINEERING 8 ABACUS INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 48 0 1 0 0 0 3 0 2 0 0 6 60 & MANAGEMENT, MOGRA, HOOGHLY 9 ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGY, COMPUTER SCIENCE & BUSINESS SYSTEM 48 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 6 57 ADISAPTAGRAM, HOOGHLY 10 ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGY, COMPUTER SCIENCE & ENGINEERING 144 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 18 171 ADISAPTAGRAM, HOOGHLY 11 ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGY, ELECTRICAL & ELECTRONICS ENGINEERING 52 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 3 6 63 ADISAPTAGRAM, HOOGHLY 12 ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGY, ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING 52 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 3 6 63 ADISAPTAGRAM, HOOGHLY 13 ACADEMY OF TECHNOLOGY, -

West Bengal Education Commission Members on 17.01.2014,

Government of West Bengal West Bengal Education Commission Supplementary Annexure II to Final Report Contents Proceedings of the meeting of the Education Commission on 25th November 2013, ............................... 3 Proceedings of the Meeting of West Bengal Education Commission Members on 17.01.2014, ............... 9 Record notes of meeting with selected representatives from Schools - 18.01.2014 .............................. 21 Record Notes for Meeting with Selected University Vice Chancellors held on 17.02.14 at Nano Technology Centre, Calcutta University ................................................................................................... 26 Record Notes for Meeting with Selected College Principals held on 18th February, 2014 at IACS, Kolkata .................................................................................................................................................................. 31 Proceedings of the Meeting of West Bengal Education Commission Members on 19.02.14 .................. 39 Proceedings of Meeting with representatives from Madrasah Education of West Bengal held on 03.03.14 .................................................................................................................................................... 48 Record Notes of Meeting with Various Teachers’ Associations of West Bengal on 19.03.14.................. 51 Proceedings of the Meeting of West Bengal Education Commission WBEC Members on 20.03.14 ....... 55 Record Notes of the Meeting with Principals of Christian -

Prospectus 2021-22

PROSPECTUS 2021-22 VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY MIDNAPORE -721 102, WEST BENGAL, INDIA Downloaded from Vidyasagar University; Copyright (c) Vidyasagar University http://ecircular.vidyasagar.ac.in/DownloadEcircular.aspx?RefId=202108298808 From the desk of Vice-Chancellor Let me take this opportunity to welcome you to Vidyasagar University. Created as a State University in 1981, the fledgeling institution flourished rapidly. Having begun on a modest scale in 1985-86, with six post-graduate departments, the University now conducts studies in frontier and interdisciplinary areas of science, social science, humanities and commerce, spread across twenty seven PG departments. The University is proud of its highly qualified and dedicated faculty members, motivated students and research scholars, and adequately equipped supporting and administrative staff who are capable of assimilating the forces of modernization and globalization in the field of higher education. The University is named after Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, the legendary 19th century pioneering social reformer, social activist, litterateur who was dedicated to the cause of the upliftment of women. Since its inception the University has committed itself to the goal of teaching and learning in higher education, ensuring quality education and providing research and extra-curricular activities in the best possible manner in order to spread the benefit of higher education in a location which is relatively backward but which has a glorious history of playing a lead role in the freedom struggle of India. Within the last nine years of its existence, the University has registered its growth both qualitatively and quantitatively. Post- Graduate studies are conducted not only in 27 departments of the University but also in 35 colleges /institutions as well. -

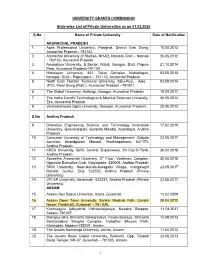

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-Wise List of Private

UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION State-wise List of Private Universities as on 01.02.2020 S.No Name of Private University Date of Notification ARUNACHAL PRADESH 1. Apex Professional University, Pasighat, District East Siang, 10.05.2013 Arunachal Pradesh - 791102. 2. Arunachal University of Studies, NH-52, Namsai, Distt – Namsai 26.05.2012 - 792103, Arunachal Pradesh. 3. Arunodaya University, E-Sector, Nirjuli, Itanagar, Distt. Papum 21.10.2014 Pare, Arunachal Pradesh-791109 4. Himalayan University, 401, Takar Complex, Naharlagun, 03.05.2013 Itanagar, Distt – Papumpare – 791110, Arunachal Pradesh. 5. North East Frontier Technical University, Sibu-Puyi, Aalo 03.09.2014 (PO), West Siang (Distt.), Arunachal Pradesh –791001. 6. The Global University, Hollongi, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 18.09.2017 7. The Indira Gandhi Technological & Medical Sciences University, 26.05.2012 Ziro, Arunachal Pradesh. 8. Venkateshwara Open University, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. 20.06.2012 S.No Andhra Pradesh 9. Bharatiya Engineering Science and Technology Innovation 17.02.2019 University, Gownivaripalli, Gorantla Mandal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh 10. Centurian University of Technology and Management, Gidijala 23.05.2017 Junction, Anandpuram Mandal, Visakhapatnam- 531173, Andhra Pradesh. 11. KREA University, 5655, Central, Expressway, Sri City-517646, 30.04.2018 Andhra Pradesh 12. Saveetha Amaravati University, 3rd Floor, Vaishnavi Complex, 30.04.2018 Opposite Executive Club, Vijayawada- 520008, Andhra Pradesh 13. SRM University, Neerukonda-Kuragallu Village, mangalagiri 23.05.2017 Mandal, Guntur, Dist- 522502, Andhra Pradesh (Private University) 14. VIT-AP University, Amaravati- 522237, Andhra Pradesh (Private 23.05.2017 University) ASSAM 15. Assam Don Bosco University, Azara, Guwahati 12.02.2009 16. Assam Down Town University, Sankar Madhab Path, Gandhi 29.04.2010 Nagar, Panikhaiti, Guwahati – 781 036. -

Institutes & No. of Seats, JELET-2020

Institutes No. of seats, JELET-2020 Institute Name Branch Name Total Cooch Behar Government Engineering College, Civil Engineering 18 Cooch Behar Computer Science & Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology 10 Electronics & Communication Engineering/Electronics & Telecommunication Engineering 15 Electrical Engineering 20 Mechanical Engineering 22 Goverment College of Engineering and Leather Computer Science & Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology 22 Technology, Kolkata Information Technology 10 Leather Technology 17 Govt. College of Engg. & Textile Technology, Computer Science & Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology 11 Berhampore Electrical Engineering 6 Mechanical Engineering 10 Textile Technology 14 Govt. College of Engineering & Ceramic Ceramic Enginering And Technology 11 Technology, Kolkata Computer Science & Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology 13 Information Technology 5 Govt. College of Engineering & Textile Apparel & Production Management 12 Technology, Serampore Computer Science & Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology 15 Information Technology 18 Textile Technology 12 Jalpaiguri Goverment Engineering Civil Engineering 16 College,Jalpaiguri Computer Science & Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology 15 Electronics & Communication Engineering/Electronics & Telecommunication Engineering 19 Electrical Engineering 19 Information Technology 22 Mechanical Engineering 20 Kalyani Goverment Engineering College, Kalyani, Computer Science & Engineering/ Computer Science & Technology 9 Nadia Electronics & Communication -

Low Mean & High Variance: Quality of Primary Education in Rural West Bengal

A STUDY SUPPORTED BY THE SIR RATAN TATA TRUST Low Mean & High Variance: Quality of Primary Education in Rural West Bengal JYOTSNA JALAN with Jharna Panda CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES, CALCUTTA Low Mean & High Variance: Quality of Primary Education in Rural West Bengal JYOTSNA JALAN with Jharna Panda CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES, CALCUTTA 2010 Director’s Message Since Independence, the focus of government interventions in primary education has been on increasing access to schools. Today net primary school enrollments in India are over ninety percent. Even in very remote areas of India, it is likely that there is a primary school. But whether these schools are functioning efficiently or whether children are learning in these schools is another matter. The Right to Education 2009 bill is also largely silent about the quality of education that is to be provided to children 6•14 years. Only indirect references are made regarding steps to improve the quality of primary education. Scattered evidence on learning achievements of primary school students indicates very low knowledge levels. Time has come to move beyond strategies to increase enrollments and to focus attention on the quality of learning in schools. This timely report provides rigorous evidence from rural West Bengal on the quality of learning in primary school and its correlates at different levels: students, households, schools, local communities, and school administration. The research shows that learning achievements in numeracy and language skills are very low among Class IV students (terminal year in primary school in West Bengal). Yet there is substantial heterogeneity across districts, administrative blocks and schools, and among people belonging to different socio-economic groups.