Innovative Ideas in Civic Engagement Across Two-Year and Four-Year Colleges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academy Sports & Outdoors Breaks Ground, Additional Tenants

Volume 2, Issue 2 June 2016 The Insider Academy Sports & Outdoors Breaks Ground, Additional Tenants Announced Officials provide a symbolic start to the construction of the Valley Ranch Town Center’s third anchor store with a groundbreaking ceremony. From left to right: Brady Wilkins (The Signorelli Company), Mark McConnell (Arch-Con), EMCID Director Isidor Ybarra, Danny Signorelli (The Signorelli Company), EMCID Chairman of the Board Brenda Webb, Michael Scheurich (Arch-Con), EMCID President and CEO Frank McCrady, and EMCID Directors Scott Hesson and Martin Zepeda. Construction is now vertical at the Valley Ranch Town In a move designed to encourage additional job opportunities Center in Porter. Officials with the East Montgomery County for residents in East Montgomery County, EMCID’s Board Improvement District and The Signorelli Company held a of Directors agreed to provide space for interviews and groundbreaking ceremony for Academy Sports + Outdoors applicant screening for Academy’s growth. Tuesday, April 5. Construction on the sports, outdoor and “As other tenants secure retail space, our Board will ensure lifestyle center began, however, in March. It joins the Kroger that employment/interview facilities are available within the Marketplace and Sam’s Club as anchor stores for the 1.8 district’s boundaries to ensure the greatest utilization of local million square foot mixed-use development at the Grand residents for these employment opportunities,” said Frank Parkway and Interstate 69. McCrady, President and CEO. Additional tenants, including Chickfila, Chili’s, El Pollo Loco, For updates on development at the Valley Ranch Town Freebirds, GNC, Nails of America, SportClips, Subway, Center and in East Montgomery County, visit www.emctx. -

Lone Star College Spring 2015 High School Graduates from Service Area Isds and High Schools Enrolled at LSC Official Day Fall 2015

Lone Star College Spring 2015 High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Enrolled at LSC Official Day Fall 2015 ISD High School Total Aldine Aldine High School 146 20.8% Benjamin O Davis High School 123 17.5% Carver High School 41 5.8% Eisenhower High School 91 12.9% Hall Center for Education 5 0.7% MacArthur High School 181 25.7% Nimitz High School 103 14.7% Victory Early College High School 13 1.8% Aldine Total 703 100.0% Cleveland Cleveland High School 41 100.0% Cleveland Total 41 100.0% Conroe Caney Creek High School 72 10.3% Conroe High School 157 22.4% Hauke Academic Alternative High School 14 2.0% Oak Ridge High School 191 27.2% The Woodlands College Park High School 114 16.2% The Woodlands High School 154 21.9% Conroe Total 702 100.0% Cy-Fair Cy-Fair High School 171 8.8% Cypress Creek High School 179 9.2% Cypress Falls High School 186 9.5% Cypress Lakes High School 261 13.4% Cypress Ranch High School 183 9.4% Cypress Ridge High School 177 9.1% Cypress Springs High School 148 7.6% Cypress Woods High School 185 9.5% Jersey Village High School 213 10.9% Langham Creek High School 228 11.7% Windfern High School 23 1.2% Cy-Fair Total 1,954 100.0% Humble Atascocita High School 202 28.8% Humble High School 87 12.4% Kingwood High School 141 20.1% Kingwood Park High School 115 16.4% Quest High School 18 2.6% Summer Creek High School 138 19.7% Humble Total 701 100.0% Huntsville Huntsville High School 42 100.0% Huntsville Total 42 100.0% Analytics and Institutional Reporting 1 Lone Star College Spring 2015 High School Graduates -

Lone Star College System Spring 2014 High School Graduates From

Lone Star College System Spring 2014 High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Enrolled at LSCS Official Day Fall 2014 ISD High School Total Aldine Aldine High School 116 18.0% Carver High School 55 8.5% Eisenhower High School 150 23.3% Hall Center for Education 13 2.0% MacArthur High School 145 22.5% Nimitz High School 152 23.6% Victory Early College High School 14 2.2% Aldine Total 645 100.0% Cleveland Cleveland High School 33 100.0% Cleveland Total 33 100.0% Conroe Caney Creek High School 108 14.0% Conroe High School 163 21.2% Hauke Academic Alternative High School 11 1.4% Oak Ridge High School 205 26.7% The Woodlands College Park High School 130 16.9% The Woodlands High School 152 19.8% Conroe Total 769 100.0% Cy-Fair Cy-Fair High School 175 9.3% Cypress Creek High School 225 11.9% Cypress Falls High School 205 10.9% Cypress Lakes High School 195 10.3% Cypress Ranch High School 135 7.2% Cypress Ridge High School 202 10.7% Cypress Springs High School 130 6.9% Cypress Woods High School 175 9.3% Jersey Village High School 242 12.8% Langham Creek High School 178 9.4% Windfern High School 26 1.4% Cy-Fair Total 1,888 100.0% Humble Atascocita High School 197 30.3% Humble High School 69 10.6% Kingwood High School 122 18.8% Kingwood Park High School 119 18.3% Quest High School 45 6.9% Summer Creek High School 98 15.1% Humble Total 650 100.0% Huntsville Huntsville High School 41 100.0% Huntsville Total 41 100.0% Katy* Cinco Ranch High School 57 10.4% James E Taylor High School 65 11.9% Katy High School 74 13.5% Martha Raines -

State Representative

Please note the information in this electronic version of the guide is an export from the online Voter Guide database as of 3PM, October 15, 2018. The candidates have the option to further update their submissions and those updates will not be reflected in this electronic version of the guide. State Representative State Representative District 3 Description: What Do They Do? A short video explanation of state elected offices: https://youtu.be/uqd9IWpSqXI 2-year term. The House is one of two chambers that make up the Texas Legislature. The representative is one of 150 representatives. They make and vote on laws, decide where the money goes within the state government, serve on committees such as agriculture and livestock, business and industry, elections, higher education, energy resources, etc. Bills for raising money must originate in the House. Only the House can impeach a statewide officer. Current salary: $7,200 plus $190 per diem when in session. Candidates (choose 1): Cecil Bell Jr. Party: Rep No response received from candidate. Lisa Seger Party: Dem Website: http://lisaforhd3.org |Facebook: http://facebook.com/LisaForHD3/ |Twitter: twitter.com/LisaForTXHD3 |Email: [email protected] |Video: https://www.youtube.com/v/zVV467nIOac Questions: Q: Background: What training, experience, and background qualify you for this position? A: I am a farmer and small business owner. I co-founded, and sit on the board of, a women’s health charity. I have spearheaded community support projects after our two biggest natural disasters in the district. All of these have honed my problem solving skills and legislation is, when done correctly, solving people’s pressing problems. -

Classroom Notes Plus: a Quarterly of Teaching Ideas, 1999- 2000 INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 853 CS 511 970 TITLE Classroom Notes Plus: A Quarterly of Teaching Ideas, 1999- 2000 INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISSN ISSN-0738-8624 PUB DATE 2000-04-00 NOTE 121p.; For volume 16, see ED 475 464. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, Notes Plus, 1111 W. Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801-1096. Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Fax: 217-328-9645; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) JOURNAL CIT Classroom Notes Plus; v17 n1-4 Aug 1999-Apr 2000 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *Classroom Techniques; *Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; Instructional Effectiveness; *Language Arts; Learning Activities; *Reading Strategies; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS National Council of Teachers of English ABSTRACT "Classroom Notes Plus" publishes descriptions of original, unpublished teaching practices or adapted ideas. Each issue also contains sections on Teacher Talk, Classroom Solutions, and Webresources. The August 1999 issue contains the following materials: Ideas from the Classroom- "Parody: Getting the Joke with Style" (Bonnie Watkins); "Keeping Organized" (Dianne Robinson); "Using Pop-Up Books" (Rose Reissman); "Students Stage Shakespeare" (Emily Moorer); Focus on Poetry-"Odes of Joy" (Mary Ann Paul); "Silhouette Poems" (JoAnn Livermore); "Building Creative Characters" (Cathy Bankston); Focus on Literature-"Noticing the Color Purple" (Mari M. McLean and Christine Gibson); "Practice with Critical Analysis" (Leslie Oster); "Using Themes in Literature" (Dorothea Susag);. and Traci's Lists of Ten-"Ten Ways to Respond to Student Drafts" (Traci Gardner). -

GRP Exhibit2

ùú1791 Sam Houston National Forest Sam Houston National Forest MEEKER, MARC ROGER )" GULF COAST TRADES CENTER SOUTH CENTRAL WATER CO )" )" MONTGOMERY COUNTY FWSD 7 CORINTHIAN POINT MUD 2 CORINTHIAN POINT MUD NO 2 US)" LAND CORP CONROE)" BAY CIVIC ASSN )" BISHOP TRAVIS LYNN WALNUT COVE WSC )" )" AQUA UTILITIES INC UTILITIES INVESTMENT CO INC )" )" ")75 ENTERGY TEXAS INC CANEY CREEK UTILITIES INC RANCH UTILITIES LP MONTGOMERY COUNTY MUD 038 )" )" )" C&R WATER SUPPLY INC )" THIRTY-TWO REAL ESTATE INVESTMENT LTD ENTERGY TEXAS INC ùú1097 )" POWER GENERATION)" LYNN LUCAS MIDDLE SCHOOL POINT AQUARIUS MUD WILLIS LAKE CONROE HILLS MUD 1097 MONTGOMERY COUNTY MUD 018 ùú POINT AQUARIUS MUD LAKE )"CONROE HILLS MUD TEXAS NATIONAL MUD )" )" MONTGOMERY COUNTY MUD NO 18 )" TEXAS NATIONAL MUD MONTGOMERY COUNTY FWSD 6 MONTGOMERY COUNTY UD NO 2 ùú2432 BENTWATER COUNTRY CLUB )" SMITH RIDGE MUD MONTGOMERY COUNTY UD 2 ùú1484 FAR HILLS UTILITY DISTRICT )" ùú830 CITY OF WILLIS CITY OF MONTGOMERY )" )" CITY OF MONTGOMERY MONTGOMERY COUNTY MUD 008 )" MHC TT INC WILLIS HIGH SCHOOL MONTGOMERY)" COUNTY MUD 009 )" BRABHAM MIDDLE SCHOOL DEL LAGO ESTATES WSC MONTGOMERY COUNTY MUD NO 8 )" WALDEN GOLF CLUB )" MONTGOMERY COUNTY MUD NO 8 FAR HILLS UD MONTGOMERY HIGH SCHOOL MONTGOMERY MONTGOMERY JR HIGH SCHOOL )" STANLEY LAKE MUD CITY OF MONTGOMERY )" ALGONQUIN WATER RESOURCES OF TEXAS LLC )" )" )" KAMPGROUNDS OF AMERICA INC CITY OF CONROE STANLEY LAKE MUD )" ùú149 UA HOLDINGS 1994-5 )" APRIL PLAZA MARINA INC CITY OF CONROE CITY OF PANORAMA VILLAGE MARTIN CREEK MUD )" DIAMONDHEAD -

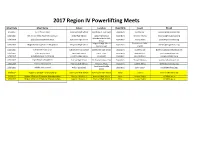

2017 Region IV Powerlifting Meets

2017 Region IV Powerlifting Meets Meet Date Meet Name School Location Boys/Girls Coach Email 1/7/2017 Gator Power Meet Dickinson High School McAdams Jr. High Gym Boys/Girls Earl Ricicar [email protected] 1/14/2017 9th Annual Milby Powerlifting Classic Milby High School Jones High School Boys/Girls Terrence Murray [email protected] Splendora Junior High 1/14/2017 Splendora Powerlifting Meet Splendora High School Boys/Girls Jeramy Willis [email protected] School Magnolia High School Troy Hebert / Mike 1/14/2017 Magnolia Bulldog Power Lifting Meet Magnolia High School Boys/Girls [email protected] Auxiliary Gym Cranfill 1/21/2017 Colmesneil Invitational Colmesneil High School Colmesneil High School Boys/Girls Darrell Cruse [email protected] 1/21/2017 Edna Invitational Edna High School Edna, Texas Boys/Girls Ron Arnesen [email protected] 1/28/2017 Industrial Cobra Invitational Industrial High school Vanderbilt Boys/Girls Wes McGinnis [email protected] 2/11/2017 Tiger Power Lifting Meet Conroe High School 9th Grade Campus Gym Boys/Girls Shawn Halloran [email protected] 2/11/2017 Palacios Invitational Palacios High School Palacios, Texas Boys/Girls Dale Mullenix [email protected] Lynn Lucas Middle 2/18/2017 Wildkat Invitational Willis High School Boys/Girls Jamin Savell [email protected] School 3/4/2017 Region IV Division I Championship Katy Taylor High School Katy Taylor High School Boys J Jensen [email protected] 3/9/2017 Region 4 Division 3 Regional Championships Region 4 Division 3 Anahuac High School Boys George Taylor [email protected] 3/10/2017 Region 4 Division 2 Regional Championships Region 4 Division 2 Anahuac High School Boys George Taylor [email protected]. -

ISD High School Feeder

Lone Star College Recent High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Enrolled at LSC Summary Official Day Fall 2019 ISD High School Total Aldine ISD Aldine Senior High School 129 15.6% Benjamin O Davis High School 155 18.7% Eisenhower High School 98 11.8% G W Carver High School 56 6.8% Macarthur High School 211 25.5% Nimitz High School 161 19.4% Victory Early College High Sch 14 1.7% W T Hall High School 4 0.5% Aldine ISD Total 828 100.0% Cleveland ISD Cleveland High School 62 100.0% Cleveland ISD Total 62 100.0% Conroe ISD Caney Creek High School 121 11.7% Conroe High School 240 23.2% Hauke Academic Alternative Hs 17 1.6% Oak Ridge High School 247 23.9% The Woodlands College Park HS 175 16.9% The Woodlands High School 234 22.6% Conroe ISD Total 1,034 100.0% Cypress-Fairbanks ISD Cy-Fair Senior High School 202 8.5% Cypress Creek High School 191 8.1% Cypress Falls High School 275 11.6% Cypress Lakes High School 259 10.9% Cypress Ranch High School 227 9.6% Cypress Ridge High School 187 7.9% Cypress Springs High School 251 10.6% Cypress Woods High School 229 9.7% Jersey Village High School 277 11.7% Langham Creek High School 268 11.3% Analytics and Institutional Reporting Page 1 of 28 Lone Star College Recent High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Enrolled at LSC Summary Official Day Fall 2019 ISD High School Total Cypress-Fairbanks ISD Windfern High School 4 0.2% Cypress-Fairbanks ISD Total 2,370 100.0% Humble ISD Atascocita High School 229 32.6% Humble High School 81 11.5% Kingwood High School 133 18.9% Kingwood Park Hs 129 18.4% Quest Early College High Schoo 9 1.3% Summer Creek High School 121 17.2% Humble ISD Total 702 100.0% Huntsville ISD Huntsville High School 47 100.0% Huntsville ISD Total 47 100.0% Katy ISD Cinco Ranch High School 64 8.1% James E Taylor High School 97 12.2% Katy High School 119 15.0% Martha Raines High School 8 1.0% Mayde Creek High School 160 20.2% Morton Ranch High School 205 25.8% Obra D. -

THECB Appendices 2011

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Summer 2011 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Summer 2011 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6147 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities .................................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities ........................................................................ A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges................................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges .................................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies .................................................................... A.5 Health-Related -

Lone Star College System Spring 2014 High School Graduates From

Lone Star College System Spring 2014 High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Enrolled at LSCS Day 1 Fall 2014 ISD High School Total Aldine Aldine High School 112 18.1% Carver High School 55 8.9% Eisenhower High School 142 22.9% Hall Center for Education 10 1.6% MacArthur High School 142 22.9% Nimitz High School 144 23.3% Victory Early College High School 14 2.3% Aldine Total 619 100.0% Cleveland Cleveland High School 34 100.0% Cleveland Total 34 100.0% Conroe Caney Creek High School 105 13.9% Conroe High School 163 21.6% Hauke Academic Alternative High School 10 1.3% Oak Ridge High School 201 26.6% The Woodlands College Park High School 127 16.8% The Woodlands High School 150 19.8% Conroe Total 756 100.0% Cy-Fair Cy-Fair High School 168 9.1% Cypress Creek High School 221 11.9% Cypress Falls High School 199 10.8% Cypress Lakes High School 190 10.3% Cypress Ranch High School 134 7.2% Cypress Ridge High School 199 10.8% Cypress Springs High School 124 6.7% Cypress Woods High School 171 9.2% Jersey Village High School 242 13.1% Langham Creek High School 175 9.5% Windfern High School 28 1.5% Cy-Fair Total 1,851 100.0% Humble Atascocita High School 195 31.6% Humble High School 66 10.7% Kingwood High School 123 19.9% Kingwood Park High School 120 19.4% Quest High School 19 3.1% Summer Creek High School 94 15.2% Humble Total 617 100.0% Huntsville Huntsville High School 41 100.0% Huntsville Total 41 100.0% Klein Klein Collins High School 210 26.3% Klein Forest High School 186 23.3% Klein High School 170 21.3% Klein Oak High -

Enrollment for the System and LSC-Kingwood Are On-Going As of 9/11/2017 Due to the Flooding in Kingwood from Hurricane Harvey

Lone Star College High School Feeder Report Official Day Fall 2017 *Enrollment for the System and LSC-Kingwood are on-going as of 9/11/2017 due to the flooding in Kingwood from Hurricane Harvey. A new Official Day has been set for LSC-Kingwood, 10/3/2017. This report will be updated after October 3, 2017. Lone Star College Spring 2017 High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Enrolled at LSC Official Day Fall 2017 ISD High School Total Aldine ISD Aldine High School 176 22.9% Benjamin O Davis High School 107 13.9% Carver High School 47 6.1% Eisenhower High School 93 12.1% Hall Center for Education 4 0.5% MacArthur High School 211 27.4% Nimitz High School 125 16.2% Victory Early College High School 7 0.9% Aldine ISD Total 770 100.0% Cleveland ISD Cleveland High School 29 100.0% Cleveland ISD Total 29 100.0% Conroe ISD Caney Creek High School 101 11.7% Conroe High School 180 20.9% Hauke Academic Alternative High School 8 0.9% Oak Ridge High School 239 27.8% The Woodlands College Park High School 153 17.8% The Woodlands High School 180 20.9% Conroe ISD Total 861 100.0% Cy-Fair ISD Cy-Fair High School 207 8.8% Cypress Creek High School 215 9.1% Cypress Falls High School 267 11.4% Cypress Lakes High School 297 12.6% Cypress Ranch High School 232 9.9% Cypress Ridge High School 207 8.8% Cypress Springs High School 238 10.1% Cypress Woods High School 177 7.5% Jersey Village High School 273 11.6% Langham Creek High School 235 10.0% Windfern High School 2 0.1% Cy-Fair ISD Total 2,350 100.0% Analytics and Institutional Reporting -

Lone Star College System Spring 2013 High School Graduates from Service Area Isds and High Schools Attending LSCS in Fall 2013

Lone Star College System Spring 2013 High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Attending LSCS in Fall 2013 Total ISD High School # % Aldine Aldine High School 135 18% Carver Career Academy 55 7% Eisenhower High School 145 20% Hall High School 22 3% Macarthur High School 180 24% Nimitz High School 190 26% Victory Early College High School 12 2% Aldine Total 739 100% Cleveland Cleveland High School 30 100% Cleveland Total 30 100% Conroe Caney Creek High School 70 10% Conroe High School 143 19% Hauke Academic Alternative High School 5 1% Oak Ridge High School 219 30% The Woodlands College Park High School 151 21% The Woodlands High School 148 20% Conroe Total 736 100% Cy-Fair Cy-Fair High School 180 9% Cypress Creek High School 207 10% Cypress Falls High School 251 12% Cypress Lake High School 1 0% Cypress Lakes High School 244 12% Cypress Ranch High School 156 8% Cypress Ridge High School 176 9% Cypress Springs High School 181 9% Cypress Woods High School 183 9% Jersey Village High School 239 12% Langham Creek High School 194 10% Windfern High School 21 1% Cy-Fair Total 2,033 100% Humble Atascocita High School 212 28% Humble High School 88 12% Kingwood High School 161 21% Kingwood Park High School 133 18% Quest High School 73 10% Summer Creek High School 86 11% Humble Total 753 100% Huntsville Huntsville High School 55 100% Huntsville Total 55 100% Office of Research and Institutional Effectiveness 1 of 23 Lone Star College System Spring 2013 High School Graduates from Service Area ISDs and High Schools Attending LSCS