Planning & Development WA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metropolitan Area Recreation Advisory Group Minutes

Metropolitan Area Recreation Advisory Group Minutes Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries 264 Vincent Street, Leederville Thursday 4 July 2019 – 11am 1.0 WELCOME, ATTENDANCE AND APOLOGIES 1.1 Welcome Patrick Quigley welcomed attendees to the inaugural meeting of the Metropolitan Area Recreation Advisory Group (MARAG). Patrick advised that the aim of MARAG was to provide leadership, coordination, advocacy and strategic direction relevant to the development and operation of metropolitan sport and recreation facilities, programs, services and projects. 1.2 Attending Patrick Quigley - City of South Perth David Bruce - City of Bayswater Marissa MacDonald - WALGA Jonelle Morley – DLGSC Alyce Atkinson – DLGSC Clayton White - DLGSC Leith Fradd – PLAWA Colby Halpin – City of Armadale Courtney Amlett – Town of Cambridge Dean Burton – City of Cockburn Tim Dayman – Town of Bassendean Salvatore Siciliano – Town of Bassendean Dan Barber – City of Bayswater Rachael Rowcroft – City of Gosnells Shane Fraser – City of Joondalup Stewart Winfield – Shire of Mundaring Amanda Cronin - City of Nedlands Sam Hegney – City of Rockingham Jason Parker- Shire of Serpentine-Jarrahdale Jess Fordham – City of South Perth Julie Rechichi – City of Subiaco Amy Fuller – City of Subiaco Michael Hayes – City of Subiaco Sarah Perkins – City of Swan Sarah Kitis – Town of Victoria Park Wayne Grimes – City of Vincent Sandra Watson – City of Vincent Samantha Culliver – City of Wanneroo Craig Bartlett – City of Wanneroo Wayne Stuart – City of Wanneroo Dan -

10.1.1 Local Government Reform - Update

COUNCIL MEETING 15 December 2014 10.1.1 LOCAL GOVERNMENT REFORM - UPDATE ATTACHMENTS 1. Letter Local Government Advisory Board 2. Media Statement Funding Package for Reforming Local Government 3. Media Statements Landmark Reports Sets Out New Look for Metro Perth 4. Local Government Advisory Board Notice Right to Request A Poll 5. Information Sheet Proposed City of Riversea Landmark report sets out new look for metro Perth Wednesday, 22 October 2014 Release of the Local Government Advisory Board report on metropolitan local government reform Board recommends Perth’s 30 councils be reduced to 16 Minister accepts all but two of the report’s boundary recommendations in the biggest shake-up of local government in 100 years Government to introduce City of Perth Act to reflect capital’s status New local governments will have increased financial sustainability and capacity to cope with Perth’s population growth The State Government today released the Local Government Advisory Board report, which provides the framework for the most significant reform of metropolitan local government in 100 years. Of the report's boundary recommendations for metropolitan Perth, Local Government Minister Tony Simpson has accepted all but two, those for the City of Perth/City of Vincent and the proposed City of Riversea, which includes five western suburbs councils. The Minister has rejected the Board’s recommendation for the City of Perth, on the basis that key icons such as The University of Western Australia (UWA) and the Queen Elizabeth II Medical Centre (QEII), were not included. As a result of the flow-on effects from City of Perth changes, he has also rejected the recommendation for the proposed City of Riversea, which includes five western suburbs councils. -

Eric Street Local Centre Additional

TOWN OF COTTESLOE TOWN OF COTTESLOE LOCAL PLANNING SCHEME NO. 3 AMENDMENT NO. 7 PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT ACT 2005 RESOLUTION DECIDING TO AMEND A LOCAL PLANNING SCHEME TOWN OF COTTESLOE LOCAL PLANNING SCHEME NO. 3 AMENDMENT NO. 7 RESOLVED that the Council, in pursuance of Section 75 of the Planning and Development Act 2005, amend the above local planning scheme by: a) Amending Schedule 2 - Additional Uses of the Town of Cottesloe Local Planning Scheme No. 3 as follows: No. Description of land Additional use Conditions A10 Lot 50 (RN 36) Eric Medical Centre. Use and/or development of the site for Street, Cottesloe. Additional Uses shall be subject to planning approval. b) Modifying the Scheme Maps accordingly to reflect the Additional Use No. A10 over Lot 50 Eric Street, Cottesloe as provided for on the attached Scheme Amendment Map. The Amendment is standard under the provisions of the Planning and Development (Local Planning Schemes) Regulations 2015 (the Regulations) for the following reasons: 1. Pursuant to Regulation 34(a) of the Regulations, the amendment relates to a zone that is consistent with the objectives identified in the scheme for that zone or reserve; 2. Pursuant to Regulation 34(e) of the Regulations, it is considered that the amendment would have minimal impact on land in the scheme area that is not the subject of the amendment; and 3. Pursuant to Regulation 34(f) of the Regulations, it is considered that the amendment does not result in any significant environmental, social, economic or governance impact on land in the scheme area. -

Recreational Waters Bacterial Quality Monitoring Program Swan and Canning Rivers - Global Positioning System - Reference Points

Recreational Waters Bacterial Quality Monitoring Program Swan and Canning Rivers - Global Positioning System - Reference Points GPS Deci GPS Deci Water Site Code Site Name LGA District Managing Authority Degs_S Degs_E body EV3/522 Sandy Beach Reserve -31.92215 115.95087 BASSENDEAN Town of Bassendean River EV3/548 Point Reserve (Nth Jetty) -31.9041 115.962726 BASSENDEAN Town of Bassendean River EV3/523 Hind Reserve (Garratt Rd - Jetty) -31.93125 115.91724 BAYSWATER City of Bayswater River EV3/541 East St Maylands Yacht Club -31.93723 115.89096 BAYSWATER City of Bayswater River EV3/517 Garvey Park (Fauntleroy Ave) -31.92121 115.94295 BELMONT City of Belmont River Belmont Park Beach (End Beach - EV3/538 -31.95349 115.89873 BELMONT City of Belmont River Goodwood Pd) EV3/539 Cracknell Park (Riversdale Rd) -31.95391 115.90326 BELMONT City of Belmont River EV3/542 Shelly Beach (Near Drain) -32.02762 115.88249 CANNING City of Canning River EV3/547 Clontarf Bay (Cadets) -32.02088 115.89865 CANNING City of Canning River EV3/545 Preston Point - John Tonkin Park -32.02903 115.76196 EAST FREMANTLE Town of East Fremantle River EV3/505 Bicton Baths -32.0276 115.77819 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/507 Cunningham St (Applecross) -32.02252 115.82608 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/532 Point Walter (Kiosk) -32.01294 115.79115 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/533 Point Walter (Boat Ramps) -32.0121 115.78834 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/534 Waylen Bay (Scout Hall) -32.00445 115.84057 MELVILLE City of Melville River EV3/540 Deep Water Point -

Town of East Fremantle News JULY 2015

Town of East Fremantle News JULY 2015 TOWN OF EAST FREMANTLE UPCOMING EVENTS Art Exhibition Army Art – Strategic Community 7-9 August at Leeuwin Barracks Council Meetings - Plan - Biennial Review 21 July 2015, 18 August 2015 With amalgamation well behind us, the Town of East Garage Sale Trail – Fremantle elected members and staff recently embarked 26 October 2015 on the two year (biennial) review of the Town’s Strategic Community Plan 2013-2023 (the Plan). The Plan was initially developed and was a key factor in deciding whether the the consultation and engagement process adopted by Council in 2013 and sets out direction of the Plan was still relevant. will be widely advertised to ensure there the vision, aspirations and objectives for is an opportunity for stakeholders and There has been some rewording of the Town over the next 10 years. And, to community members to get involved. the Plan to include Governance and ensure that what is planned for can be Leadership and Council is confident that A copy of the (revised) Strategic achieved, consideration is given to the the strategic direction outlined in the Community Plan 2013-2023 will be financial, asset and workforce constraints updated Plan will in turn shape actions available late July - please go to our that we work within. that will deliver realistic benefits for the website www.eastfremantle.wa.gov.au or With that in mind the review process community. email [email protected] to involved a number of workshops with the obtain a copy. The Council is looking forward to the Mayor, Councillors and senior staff who set major review of the Plan, which will involve about reconsidering the stated objectives a comprehensive community consultation in the Plan. -

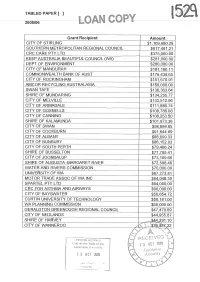

Tabled Paper [I

TABLED PAPER [I 2005/06 Grant Recipient Amount CITY OF STIRLING 1,109,680.28 SOUTHERN METROPOLITAN REGIONAL COUNCIL $617,461.21 CRC CARE PTY LTD $375,000.00 KEEP AUSTRALIA BEAUTIFUL COUNCIL (WA) $281,000.00 DEPT OF ENVIRONMENT $280,000.00 ITY OF MANDURAH $181,160.11 COMMONWEALTH BANK OF AUST $176,438.65 CITY OF ROCKINGHAM $151,670.91 AMCOR RECYCLING AUSTRALASIA 50,000.00 SWAN TAFE $136,363.64 SHIRE OF MUNDARING $134,255.77 CITY OF MELVILLE $133,512.96 CITY OF ARMADALE $111,880.74 CITY OF GOSNE LS $108,786.08 CITY OF CANNING $108,253.50 SHIRE OF KALAMUNDA $101,973.36 CITY OF SWAN $98,684.85 CITY OF COCKBURN $91,644.69 CITY OF ALBANY $88,699.33 CITY OF BUNBURY $86,152.03 CITY OF SOUTH PERTH $79,466.24 SHIRE OF BUSSELTON $77,795.41 CITY OF JOONDALUP $73,109.66 SHIRE OF AUGUSTA -MARGARET RIVER $72,598.46 WATER AND RIVERS COMMISSION $70,000.00 UNIVERSITY OF WA $67,272.81 MOTOR TRADE ASSOC OF WA INC $64,048.30 SPARTEL PTY LTD $64,000.00 CRC FOR ASTHMA AND AIRWAYS $60,000.00 CITY OF BAYSWATER $50,654.72 CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY $50,181.00 WA PLANNING COMMISSION $50.000.00 GERALDTON GREENOUGH REGIONAL COUN $47,470.69 CITY OF NEDLANDS $44,955.87_ SHIRE OF HARVEY $44,291 10 CITY OF WANNEROO 1392527_ 22 I Il 2 Grant Recisien Amount SHIRE OF MURRAY $35,837.78 MURDOCH UNIVERSITY $35,629.83 TOWN OF KWINANA $35,475.52 PRINTING INDUSTRIES ASSOCIATION $34,090.91 HOUSING INDUSTRY ASSOCIATION $33,986.00 GERALDTON-GREENOUGH REGIONAL COUNCIL $32,844.67 CITY OF FREMANTLE $32,766.43 SHIRE OF MANJIMUP $32,646.00 TOWN OF CAMBRIDGE $32,414.72 WA LOCAL GOVERNMENT -

ECM 7188816 V1 Annual Financial Report

Annual Financial Statements for the Year Ended 30 June 2010 www.cockburn.wa.gov.au Document Set ID: 7188816 55 Version: 1, Version Date: 17/01/2018 Financial Statements: Index - Statement by CEO 59 - Statement of Financial Position 60 - Statement of Equity 61 - Statement of Comprehensive Income 62 - Statement of Comprehensive Income by Nature or Type 63 - Cash Flows 64 - Rate Setting Statement 66 1. Significant Accounting Policies 68 2. Revenues and Expenses 75 a. Statement of Objectives 75 b. Control over Contributions 76 c. Asset by Function 77 d. Disposal of Assets 78 e. Changes in Net Assets 79 3. Cash & Cash Equivalents 80 4. Investments 80 5. Trade & Other Receivables 81 6. Inventories 81 7. Payables 81 a. Trade & Other Payables 81 b. Interest Bearing Liabilities 81 8. Provisions 81 9. Property, Infrastructure, Plant and Equipment 82 10. Information on Property, Infrastructure, Plant and Equipment 84 a. Movements in Carrying Amounts 84 b. Recognition of Gifted Development Assets 85 c. Revaluation of Infrastructure Assets 85 11. Reserves 86 12. Superannuation 92 13. Capital & Leasing Commitments 93 14. Notes to Cash Flow Statement 94 a. Reconciliation of Net Cash Used in Operating Activities to Change in Net Assets 94 b. Reconciliation of Cash 94 15. Interests in Joint Venture Entities (Unaudited) 95 16. Fees & Charges 96 17. Other Expenses 98 18. Financial Ratios 98 19. Discounts, Incentives, Concessions, & Write Offs 99 20. Interest Charges, Administration Fees and Instalments 100 21. Service Charges 101 a. Prescribed Service Charges 101 b. Other Service Charges 101 22. Statement of Rating Information 102 23. -

WESTERN AUSTRALIA Kings Park, Perth Kings Park

WESTERN AUSTRALIA Kings Park, Perth Kings Park, WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? STATE BY STATE WA WHAT’S HAPPENING? Average canopy cover 51% of urban WA is urban LGAs in WA have seen a 19.95% decrease in shrubs. down 2.32% from 22.27% in 2011. The City of Cockburn is of concern given that there has been a 16.6% loss in shrubbery and an almost equivalent gain in grass surfaces, suggesting that clearing may have taken place. 41% of 24% of urban LGAs in WA LGAs in WA have have experienced a seen an increase The 5% loss of canopy in the City of Cockburn is significant loss in hard surfaces. almost equivalent to that of the hard surface increase. in canopy. WHERE SHOULD ALL THE TREES GO? WESTERN AUSTRALIA WA THE MOST & LEAST VULNERABLE 2.5 Rating City of Armadale, City of Fremantle, City of Gosnells, City of Perth, City of Rockingham 3.0 Rating City of Bayswater, Town of Cambridge, Town of East Fremantle, 2.0 Rating City of Melville, City of Stirling Town of Bassendean, City of Swan, City of Wanneroo 3.5 Rating City of Joondalup, Town of Mosman Park, City of Nedlands, 1.5 Rating City of South Perth, City of Subiaco, City of Vincent City of Cockburn, Town of Victoria Park 4.0 Rating City of Canning, Town of Cottesloe, Shire of Kalamunda, 1.0 Rating Shire of Mundaring, The Shire of Peppermint Grove City of Kwinana 4.5 Rating 0.5 Rating Town of Claremont City of Belmont LEAST MOST VULNERABLE VULNERABLE TOP URBAN GREENING OPPORTUNITIES: - City of Belmont (0.5) - Town of Bassendean, City of Swan, City of Wanneroo (2) - City of Kwinana (1) - City -

DISTRICT PLANNING SCHEME No. 2

DISTRICT PLANNING SCHEME No. 2 Amendment No. 169 Planning and Development Act 2005 RESOLUTION TO PREPARE AMENDMENT TO LOCAL PLANNING SCHEME CITY OF WANNEROO DISTRICT PLANNING SCHEME NO. 2 – AMENDMENT NO. 169 RESOLVED that the local government pursuant to section 75 of the Planning and Development Act 2005, amend the above local planning scheme by: 1. Adding the following land use definition for ‘massage premises’ into Section 2 of Schedule 1: massage premises : means premises involving the massaging manipulation or other treatment of body parts for therapeutic or remedial purposes, but does not include the provision of any sexual services. 2. Inserting permissibility for the ‘massage premises’ use class into “Table 1 (Clause 3.2) - The Zoning Table” as follows: ZONES INDUSTRIAL USE MIXED USE BUSINESS COMMERCIAL CIVIC & CULTURAL PRIVATE CLUBS/RECREATION GENERAL INDUSTRIAL SERVICE RURAL GENERAL RESOURCE RURAL SPECIAL RURAL SPECIAL RESIDENTIAL LANDSCAPE ENHANCEMENT CLASSES RESIDENTIAL Massage X D P P X X X D X X X X X Premises 3. Inserting car parking standards for the ‘massage premises’ use class into “Table 2 (Clause 4.14) - Car Parking Standards” as follows: USE CLASS NUMBER OF ON-SITE CAR PARKING SPACES Commercial Massage Premises 5 per practitioner The Amendment is complex under the provisions of the Planning and Development (Local Planning Schemes) Regulations 2015 for the following reason: An amendment that is not addressed by any local planning strategy. Date of Council Resolution: 13 November 2018 ...................................................... (Chief Executive Officer) Dated this ……………. day of ………………. 20……… CITY OF WANNEROO DISTRICT PLANNING SCHEME NO 2 – AMENDMENT NO. 169 SCHEME AMENDMENT REPORT Background – Circumstances that have prompted this Amendment The City has considered over 20 development applications since 2011 for massage premises (excluding Home Businesses that offer massage). -

Street Names Index

City of Fremantle and Town of East Fremantle Street Names Index For more information please visit the Fremantle City Library History Centre Place Name Suburb Named After See Also Notes Ada Street South Fremantle Adams Street O'Connor The Adcock brothers lived on Solomon Street, Fremantle. They were both privates in the 11 th Frank Henry Burton Adcock ( - Battalion of the AIF during WWI. Frank and Adcock Way Fremantle 1915) and Fredrick Brenchley Frederick were both killed in action at the Adcock ( - 1915) landing at Gallipoli on the 25 th of April 1915, aged 21 and 24 years. Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen Adelaide Street Fremantle consort of King William IV (1830- Appears in the survey of 1833. 1837). Agnes Street Fremantle Ainslie Road North Fremantle Alcester Road East Fremantle Alcester, England Alexander was Mayor of the Municipality of Wray Avenue Fremantle, 1901-02. Alexander Road Fremantle Lawrence Alexander and Hampton Originally Hampton Street until 1901-02, then Street named Alexander Road, and renamed Wray Avenue in 1923 after W.E. Wray. Alexandra of Denmark, queen Queen Alexandra was very popular throughout Alexandra Road East Fremantle consort of King Edward VII (1901- her time as queen consort and then queen 1910). mother. 1 © Fremantle City Library History Centre Pearse was one of the original land owners in Alice Avenue South Fremantle Alice Pearse that street. This street no longer exists; it previously ran north from Island Road. Alfred Road North Fremantle Allen was a civil engineer, architect, and politician. He served on the East Fremantle Municipal Council, 1903–1914 and 1915–1933, Allen Street East Fremantle Joseph Francis Allen (1869 – 1933) and was Mayor, 1909–1914 and 1931–1933. -

Decision to Commit Funding to the Perth Freight Link Project

Chapter 4 Concerns raised by local governments and communities 4.1 This chapter discusses concerns about the Perth Freight Link raised by local governments and communities, and in particular addresses evidence concerning: • insufficient consultation on the project by the federal and state governments, especially with local governments, industry representatives, and the communities who would be affected the most; • the damage the Roe 8 extension could cause to local environmental, Indigenous and other heritage sites, as well as apparent irregularities in the overturning of previous environmental and heritage assessments; and • negative effects the project may have on local communities; and • some negative impacts the Freight Link would have for residents and businesses of Fremantle. Lack of consultation 4.2 The committee received evidence suggesting that the Commonwealth and state governments did not undertake appropriate or sufficient consultation about the Perth Freight Link with local governments, industry stakeholders and the communities who would be affected the most by the project. Local government and industry stakeholders 4.3 The Mayors of Fremantle, East Fremantle and Cockburn all told the committee their communities would be negatively affected by the Freight Link. All agreed that they first heard of the project through the media and had no contact with Main Roads WA until well after the Budget announcement had been made.1 Councillor Logan Howlett, Mayor of the City of Cockburn, reflected that the Freight Link was presented by the state government as the only potential option for transport infrastructure to support Fremantle Port: …the level of public consultation with regard to Roe 8 focused only on one option and that was to build Roe 8. -

Small Business Friendly Local Government Discussion Paper February 2020 John O’Neill – Manager Economic Development, Tourism and Marketing

10.5.1 - attachment 1 Review of Ward Boundaries and Representation – Feedback Form Small Business Friendly Local Government Discussion Paper February 2020 John O’Neill – Manager Economic Development, Tourism and Marketing Reference: HPRM OC18/20340 PageOrdinary 1 of 5 Council Meeting - 17© Shire February of Serpentine 2020 Jarrahdale 2020 10.5.1 - attachment 1 Small Business Friendly Local Government Discussion Paper Background A Notice of Motion was received from Shire President, Councillor Michelle Rich on Monday 7 October 2019 to prepare a Discussion Paper about the Small Business Friendly Local Government, as promoted by the Small Business Development Corporation and present to Council at the February 2020 Ordinary Council Meeting. Officer Commentary The Small Business Development Corporation (SBDC) has developed the Small Business Friendly Local Government (SBFLG) initiative to recognise those local government authorities (LGA’s) in Western Australia that are actively committed to supporting small businesses in their local areas. Participating LGA’s are required to sign the Small Business Friendly Local Government Charter to demonstrate they are committed to work with, and actively support local small business. A copy of this charter is attached as Attachment 1. Participating local governments are required to adopt three ‘standard‘ activities and three ‘flexible‘ activities that support and help develop local small business. Additional information is outlined in the Small Business Friendly Brochure included as Attachment 2. Local