10 Blocks Podcast "Gotham’S Bioterror Challenge"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Belief

The Atlantic Monthly | January/February 2005 STATE OF THE UNION BEYOND BELIEF The real religious divide in the United States isn't between the churched and the unchurched. It's between different kinds of believers BY HANNA ROSIN ..... Richard Land is gloating, and who can blame him? When I called him a few weeks after the 2004 election, he said he'd been driving around his home town of Nashville with his cell phone ringing constantly, CNN on one line, Time magazine on the other—everyone wanting to ask the prominent Southern Baptist how his people had managed to win the election for George W. Bush. Yes, he told me, "we white evangelicals were the driving engine" of the president's victory. But then he veered into the kind of interview a quarterback gives in the locker room, in which he thanks the offensive line and the tight end and the coach and, well, really the whole team for bringing it home. "You'd be shocked," Land said, "at the number of Catholics who voted for this president. You'd be shocked at the number of Orthodox Jews, even observant Jews. This was a victory for all people of traditional moral values." "Moral values." The phrase has turned into the hanging chad of the 2004 election, the cliché no one takes seriously. Do the debates over Iraq and the economy not involve moral values? Is everyone in the exit polls who didn't check that box a secular hedonist? As a way of explaining the outcome of the election, the "morality issue" has been amply debunked as all but meaningless. -

Defense of Animal Agriculture

DEFENSE OF ANIMAL AGRICULTURE SF SF DEFENSE OF ANIMAL AGRICULTURE BIPARTISAN REPORT OF THE BLUE RIBBON STUDY PANEL ON BIODEFENSE October 2017 www.biodefensestudy.org BLUE RIBBON STUDY PANEL ON BIODEFENSE SPECIAL FOCUS DEFENSE OF ANIMAL AGRICULTURE BIPARTISAN REPORT OF THE BLUE RIBBON STUDY PANEL ON BIODEFENSE October 2017 Copyright © 2017 by the Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense All rights reserved. www.biodefensestudy.org Cover and graphics by Delbridge Design. Base cover image courtesy of Getty Images/feoris. SUGGESTED CITATION Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense. Special Focus: Defense of Animal Agriculture. Blue Ribbon Study Panel on Biodefense: Washington, DC. October 2017. PANEL MEMBERS Joseph I. Lieberman, Chair Thomas J. Ridge, Chair Donna E. Shalala Thomas A. Daschle James C. Greenwood Kenneth L. Wainstein PANEL EX OFFICIO MEMBERS Yonah Alexander, PhD William B. Karesh, DVM Rachel Levinson, MA I. Lewis Libby, JD Gerald W. Parker, DVM, PhD George Poste, DVM, PhD, DSc Tevi Troy, PhD PANEL STAFF Ellen P. Carlin, DVM, Co-Director Asha M. George, DrPH, Co-Director Robert H. Bradley, Policy Associate Patricia Prasada-Rao, MPH, Panel Coordinator Patricia de la Sota, Meeting Coordinator Katherine P. Royce, EcoHealth Alliance Intern ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Panel thanks Hudson Institute for serving as our fiscal sponsor. The Panel also thanks Kansas State University for hosting our special focus meeting on agrodefense, and the many experts that spoke at this meeting, some of whom came from great distances to do so. We are grateful to the many individuals both inside and outside of the federal government who provided input into the report throughout its development. -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report. -

JEWISH LINK CHINESE TAKE-OUT Excludes Parties

Sun-Thurs: 11:30am-10pm Fri: 11:30am-2:30pm • Sat: Closed (Go for Pizza!!) Family Link Pg 60 Order on-Line at www.chopstixusa.com Linking Bergen, Essex, Middlesex, Passaic & Union Counties Issue #131 201-833-0200 172 West Englewood Ave. Teaneck, NJ 07666 13%OFF JL GLATT KOSHER With coupon. May not be combined with other offers JEWISH LINK CHINESE TAKE-OUT Excludes parties. Expires 6-9-16 May 20 - 12 Iyyar 5776 Parshat Emor May 19, 2016 | 11 Iyar, 5776 CANDLE Light Candles: 7:54 PM OF NEW JERSEY LIGHTING Shabbat Ends: 9:03 PM Local Students Shine at Chidon HaTanach National Finals By Elizabeth Kratz est scorers from that exam, which ternational competition, is given in Hebrew at two levels— which is annually tele- The American fi nals for the for yeshiva high school and mid- vised live from Jerusalem Chidon HaTanach, or “Bible Quiz,” dle school students—with a third on Yom Ha’atzmaut. is an exciting event held each exam given in English primarily for Dovi Nadel replaces year. Some 150 national fi nalists Sunday school students, were then Teaneck’s own Rabbi Ezra are culled from the top scorers of quizzed live, as family, friends and Frazer this year as the co- more than 400 contestants who fellow Tanach enthusiasts packed ordinator of the American take regional exams through Chi- the auditorium. The Hebrew mid- Chidon HaTanach compe- don clubs and classes, including dle school and Hebrew high school tition. Nadel, like Frazer, many from our metropolitan area. division winners are northern New is a former Chidon com- From left to right: Local residents Nechama They met last Sunday at Manhat- Jersey residents, as well as the high petitor and champion, Reichman, Uriel Simpson and Shlomi Helfgot tan Day School, where they sat for school runner-up, who, along with having won the U.S. -

Are Think Tanks Becoming Too Political?” This Session Is Sponsored by Hudson’S Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal

- Edited Transcript - presents a discussion entitled Thursday, February 16, 2012, 12:00–2:00pm Program and Panel 12:00 p.m. Panel discussion Michael Franc, Heritage Foundation Vice President for Government Studies Will Marshall, President and Founder of the Progressive Policy Institute Neera Tanden, President of the Center for American Progress Tevi Troy, Hudson Institute Senior Fellow Christopher DeMuth, Hudson Institute Distinguished Fellow and former President of the American Enterprise Institute (Moderator) 1:10 Question-and-answer session 2:00 Adjournment HUDSON INSTITUTE CHRISTOPHER DEMUTH: Ladies and gentlemen, good afternoon, welcome to Hudson Institute and this panel discussion, “Are Think Tanks Becoming Too Political?” This session is sponsored by Hudson’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy and Civic Renewal. I am Christopher DeMuth. I am a Senior Fellow here at Hudson and was, for many years, president of the American Enterprise Institute. So the subject is one of great interest to me as well. I will moderate the discussion, although after others have finished I may say a few words of my own if I think there is something to add or if I liked something that somebody else has said and want to say it myself. [LAUGHTER]. The text for our discussion is an article in the current winter issue of National Affairs by Tevi Troy entitled, “Devaluing the Think Tank.” Tevi is a Senior Fellow at Hudson. He went to Cornell and got a PhD in American Civilization at the University of Texas at Austin. In the Bush 43 Administration, he served in a succession of positions at the White House, including Deputy Director and Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy and Head of the Domestic Policy Council. -

A Move to Single-Payer Health Care? Implications for Employer-Sponsored Care

2017 A Move to Single-Payer Health Care? Implications for Employer-Sponsored Care Tevi D. Troy 2014 American Health Policy Institute (AHPI) is a non-partisan 501(c)(3) think tank, established to examine the impact of health policy on large employers, and to explore and propose policies that will help bolster the ability of large employers to provide quality, affordable health care to employees and their dependents. The Affordable Care Act has catalyzed a national debate about the future of health care in the United States, and AHPI serves to provide thought leadership grounded in the practical experience of America’s largest employers. To learn more, visit ghgvghgghghhg americanhealthpolicy.org. About the Author: Tevi Troy is the Chief Executive Officer of the American Health Policy Institute and former Deputy Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dr. Troy has served as Deputy Assistant and Acting Assistant to President George W. Bush for Domestic Policy, and in the latter position, ran the Domestic Policy Council. Research by Madeleine Nagle, University of Chicago. i Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................1 2014 Public Option in the ACA .....................................................................................4 Vermont’s Green Mountain Care ........................................................................4 ColoradoCare .........................................................................................................5 -

Infocusfocusquarterly Governing Post-Pandemic

VOLUMEVOL. 9 ISSUE 15 ISSUE 4 | FALL 2 | 2015 SPRING 2021 ininFOCUSFOCUSQUARTERLY Governing Post-Pandemic Mark Meirowitz on Hyper-Partisanship | Max Abrahms on Combatting Domestic Extremism | Peter tktk on tktk | Huessy on Nuclear Modernization | Richard W. Rahn on Stimulus-Induced Inflation | Philip Hamburger on Regulating Online Speach | Tom Finnerty on Biden’s Energy Plan | Tevi Troy on 2020 Healthcare Lessons | Ian Kingsbury and Jason Bedrick on School Choice | Paul J. Larkin Jr. on the Healing Power of Dogs | David Wurmser on Eroding Fiduciary Responsibility | Shoshana Bryen reviews The Kennedys in the World ALLIANCES:Featuring AMERICAN an Interview INTERESTS with Prof. IN A GlennCHANGING Loury WORLD LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER elcome to Spring. Daffodils Jason Bedrick consider school choice inFOCUS are up, people are being as a Jewish option. And Tevi Troy asks VOLUME 15 | ISSUE 2 vaccinated (not fast enough, what, if anything, we’ve learned about but the whole process medicine and our medical systems. Not Publisher W Matthew Brooks has been epic from the start of our all of our priorities are domestic – Peter understanding of the virus, through Huessy reminds us that nuclear mod- Editor Chinese obfuscation and lies, to tens ernization can’t be put off forever. Paul Shoshana Bryen of millions of jabs and more to come). Larkin lowers our blood pressure with Associate Editors That means Congress and the White the value of rehabilitation animals, for Michael Johnson House should be focused which we are grateful. Lisa Schiffren on where our country is Brown University Copy Editor going as the fog lifts. We, Professor Glen Loury rais- Shari Hillman at inFOCUS Quarterly es it again with a remark- Published by: are here to help with our able, no-hold-barred inter- Jewish Policy Center annual “issues issue.” view on race in America. -

Tevi Troy Noah C. Rothman Abe Greenwald

THE CAUTIONARY TALE OF SAMANTHA POWER BY SETH MANDEL FEBRUARY 2017 Commentary HOW DEMOCRATS WILL TRY TO STOP TRUMP NOAH C. TEVI ROTHMAN TROY on the sudden on bureaucratic rediscovery resistance to of checks and the new Commentary balances president FEBRUARY 2017 FEBRUARY $5.95 US : $7.00 CANADA : VOLUME 143 NUMBER 2 143 : VOLUME ABE GREENWALD on the convenient new disapproval of a make-nice-with-the-bad-guys foreign policy FEBRUARY 2017 COVER.indd 1 1/12/17 2:31 PM At Magen David Adom, we’re often saving lives before our ambulances even arrive. At Magen David Adom, Israel’s national EMS service, help begins the moment the phone is answered. Because we use EMTs to handle calls, they can provide lifesaving instructions while dispatching ambulances and first-responders on Medicycles. And now, with 15,000 CPR-certified civilian Life Guardians joining our team, help can be just seconds away. Your support makes Israel’s premier lifesaving organization even better. Make a gift today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org FEBRUARY 2017 COVER.indd 2 1/12/17 2:36 PM ‘Tough Love’—The First and Last Obama Lie WROTE AN ARTICLE in this space six months complete. And, as he had when he began it, in farewell into the Obama presidency entitled “The Turn interview after farewell interview, he characterized his I Against Israel.” It appeared in the July 2009 issue. assault on the legitimacy of the Jewish presence in the These were its concluding paragraphs: Holy Land as an act of tough love. -

Spring11 Layout 1

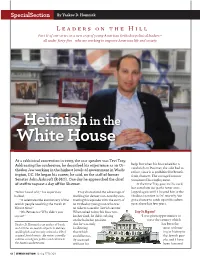

SpecialSection By Yaakov D. Homnick Leaders on the Hill Part II of our series on a new crop of young American Orthodox political leaders— all under forty-five—who are working to improve American life and society. Heimish in the White House At a rabbinical convention in 2003, the star speaker was Tevi Troy. Addressing the conference, he described his experience as an Or- help. But when his boss asked for a thodox Jew working in the highest levels of government in Wash- sandwich on Passover, the aide had to refuse, since it is prohibited to benefit ington, DC. He began his career, he said, on the staff of former from chametz. The outraged senator Senator John Ashcroft (R-MO). One day he approached the chief terminated his employment. of staff to request a day off for Shavuot. At the time Troy gave me his card, but somehow our paths never over- “Never heard of it,” his supervisor Troy dramatized the advantage of lapped again until I located him at the balked. working for devout non-Jews by con- Hudson Institute in DC recently. We “It celebrates the anniversary of the trasting this episode with the story of got a chance to catch up on his adven- Jewish people receiving the Torah at an Orthodox young man who was tures these last few years. Mount Sinai.” an aide to a secular Jewish senator. “Oh, Pentecost! Why didn’t you When asked to buy his boss non- Say It Again! say so?” kosher food, he did it, relying “I was given opportunities to on the halachic position serve the country which Yaakov D. -

A National Blueprint for Biodefense: Leadership and Major Reform Needed to Optimize Efforts

A NATIONAL BLUEPRINT FOR BIODEFENSE: LEADERSHIP AND MAJOR REFORM NEEDED TO OPTIMIZE EFFORTS BIPARTISAN REPORT OF THE BLUE RIBBON STUDY PANEL ON BIODEFENSE October 2015 Institutional Sponsors: PANEL MEMBERS Joseph I. Lieberman, Chair Thomas J. Ridge, Chair Donna E. Shalala Thomas A. Daschle James C. Greenwood Kenneth L. Wainstein i PANEL EX OFFICIO MEMBERS Yonah Alexander, Ph.D. | William B. Karesh, D.V.M. | Rachel Levinson, M.A. I. Lewis Libby, J.D. | Gerald W. Parker, D.V.M., Ph.D. George Poste, D.V.M., Ph.D., D.Sc. | Tevi Troy, Ph.D. PANEL STAFF Ellen P. Carlin, D.V.M., Co-Director | Asha M. George, Dr.P.H., Co-Director Patricia de la Sota, Staff Assistant | Stephanie Marks, J.D., Intern FOUNDING STAFF DIRECTOR Robert B. Kadlec, M.D. ii TAB LE OF CONTE NTS Panel Members ................................................................................................................................................ i Panel Ex Officio Members............................................................................................................................ ii Panel Staff ....................................................................................................................................................... ii Preface ............................................................................................................................................................ iv Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... -

OPERA – Fiche Sociographique - Santé

OPERA – fiche sociographique - santé Prénom, Nom: Tevi David Troy (formerly Troyansky) Contact : Visiting Senior felllow, Hudson Institute, Inc. 1015 18th Street, NW, 6th floor, Washington, DC 20036 Tel : (202) 974-2400 Catégorie : Exécutif Dates de naissance / décès : Né le 28 mars 1967 Lieu de naissance : Genre : Homme Lieu de résidence (si DC avant l’accession à un poste retenu, avec si possible l’année de l’emménagement à DC): Maryland Formation : BA/BS Industrial and Labor Relations, BS Cornell 1989 MA/MS MA University of Texas at Austin PhD American Civilization, University of Texas at Austin 1996 Law degree (JD…) Autre Profession initiale : Chercheur et consultant Carrière : W. Genieys, Operationalizing Programmatic Elites Research in America, OPERA : ANR-08-BLAN-0032. 1 • Research Fellow at the Hudson Institute and a Researcher at the American Enterprise Institute • 1996-1998 : Domestic Policy Analyst House Republican Policy Committee • 1999 - 2000 : Policy Director John David Ashcroft • 2000-2001 : Department of Labor, Deputy assistant secretary for policy • 2002-2003 : EOP, Domestic policy council, Special adviser to the domestic policy council • 2004 - 2004 : Special Assistant to the President and Deputy Cabinet Secretary Office of Cabinet Affairs • 2005-2008 : EOP, Domestic policy council, Deputy assistant to the President for domestic policy • Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute, a Senior Fellow at the Potomac Institute Républicain. Sources biblio/bio, articles, divers. Anciennement sur : Hudson Institute > About Hudson > Tevi Troy www.hudson.org [cached] Tevi Troy is a Senior Fellow at Hudson Institute, and a writer and consultant on health care and domestic policy. On August 3, 2007, he was unanimously confirmed by the U.S. -

Rescuing Americans from the Failed Healthcare Law and Advancing Patient-Centered Solutions

RESCUING AMERICANS FROM THE FAILED HEALTHCARE LAW AND ADVANCING PATIENT-CENTERED SOLUTIONS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND THE WORKFORCE U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD IN WASHINGTON, DC, FEBRUARY 1, 2017 Serial No. 115–1 Printed for the use of the Committee on Education and the Workforce ( Available via the World Wide Web: www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/ committee.action?chamber=house&committee=education or Committee address: http://edworkforce.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 23–826 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 10:24 May 03, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\E&W JACKETS\23826.TXT CANDRA CEWDOCROOM with DISTILLER COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION AND THE WORKFORCE VIRGINIA FOXX, North Carolina, Chairwoman Joe Wilson, South Carolina Robert C. ‘‘Bobby’’ Scott, Virginia Duncan Hunter, California Ranking Member David P. Roe, Tennessee Susan A. Davis, California Glenn ‘‘GT’’ Thompson, Pennsylvania Rau´ l M. Grijalva, Arizona Tim Walberg, Michigan Joe Courtney, Connecticut Brett Guthrie, Kentucky Marcia L. Fudge, Ohio Todd Rokita, Indiana Jared Polis, Colorado Lou Barletta, Pennsylvania Gregorio Kilili Camacho Sablan, Luke Messer, Indiana Northern Mariana Islands Bradley Byrne, Alabama Frederica S. Wilson, Florida David Brat, Virginia Suzanne Bonamici, Oregon Glenn Grothman, Wisconsin Mark Takano, California Steve Russell, Oklahoma Alma S. Adams, North Carolina Elise Stefanik, New York Mark DeSaulnier, California Rick W.