Arxiv:Math/0503724V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homogeneous Flows, Moduli Spaces and Arithmetic

CLAY MATHEMATICS INSTITUTE SUMMER SCHOOL 2007 Homogeneous Flows, Moduli Spaces and Arithmetic at the Centro di Ricerca Matematica Designed for graduate students and mathematicians within Ennio De Giorgi, Pisa, Italy five years of their PhD, the program is an introduction to the theory of flows on homogeneous spaces, moduli spaces and their many applications. These flows give concrete examples of dynamical systems with highly interesting behavior and a rich and powerful theory. They are also a source of many interesting problems and conjectures. Furthermore, understanding the dynamics of such a concrete system lends to numerous applications in number theory and geometry regarding equidistributions, diophantine approximations, rational billiards and automorphic forms. The school will consist of three weeks of foundational courses Photo: Peter Adams and one week of mini-courses focusing on more advanced topics. June 11th to July 6th 2007 Lecturers to include: Organizing Committee Nalini Anantharaman, Artur Avila, Manfred Einsiedler, Alex Eskin, Manfred Einsiedler, David Ellwood, Alex Eskin, Dmitry Kleinbock, Elon Svetlana Katok, Dmitry Kleinbock, Elon Lindenstrauss, Shahar Mozes, Lindenstrauss, Gregory Margulis, Stefano Marmi, Peter Sarnak, Hee Oh, Akshay Venkatesh, Jean-Christophe Yoccoz Jean-Christophe Yoccoz, Don Zagier Foundational Courses Graduate Postdoctoral Funding Unipotent flows and applications Funding is available to graduate students and postdoctoral fellows (within 5 Alex Eskin & Dmitry Kleinbock years of their PhD). Standard -

Diagonalizable Flows on Locally Homogeneous Spaces and Number

Diagonalizable flows on locally homogeneous spaces and number theory Manfred Einsiedler and Elon Lindenstrauss∗ Abstract.We discuss dynamical properties of actions of diagonalizable groups on locally homogeneous spaces, particularly their invariant measures, and present some number theoretic and spectral applications. Entropy plays a key role in the study of theses invariant measures and in the applications. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000). 37D40, 37A45, 11J13, 81Q50 Keywords. invariant measures, locally homogeneous spaces, Littlewood’s conjecture, quantum unique ergodicity, distribution of periodic orbits, ideal classes, entropy. 1. Introduction Flows on locally homogeneous spaces are a special kind of dynamical systems. The ergodic theory and dynamics of these flows are very rich and interesting, and their study has a long and distinguished history. What is more, this study has found numerous applications throughout mathematics. The spaces we consider are of the form Γ\G where G is a locally compact group and Γ a discrete subgroup of G. Typically one takes G to be either a Lie group, a linear algebraic group over a local field, or a product of such. Any subgroup H < G acts on Γ\G and this action is precisely the type of action we will consider here. One of the most important examples which features in numerous number theoretical applications is the space PGL(n, Z)\ PGL(n, R) which can be identified with the space of lattices in Rn up to homothety. Part of the beauty of the subject is that the study of very concrete actions can have meaningful implications. For example, in the late 1980s G. -

Notices of the Ams 421

people.qxp 2/27/01 4:00 PM Page 421 Mathematics People Bigelow and Lindenstrauss The Leonard M. and Eleanor B. Blumenthal Trust for the Advancement of Mathematics was created for the Receive Blumenthal Prize purpose of assisting the Department of Mathematics of the University of Missouri at Columbia, where Leonard The Leonard M. and Eleanor B. Blumenthal Award for the Blumenthal served as professor for many years. Its second Advancement of Research in Pure Mathematics has been awarded to STEPHEN J. BIGELOW of the University of Melbourne purpose is to recognize distinguished achievements and ELON B. LINDENSTRAUSS of Stanford University and the in the field of mathematics through the Leonard M. and Institute for Advanced Study. The awards were presented Eleanor B. Blumenthal Award for the Advancement of at the Joint Mathematics Meetings in New Orleans in January Research in Pure Mathematics, which was originally 2001. funded from the Eleanor B. Blumenthal Trust upon Mrs. Stephen Bigelow was born in September 1971 in Blumenthal’s death on July 12, 1987. Cambridge, England. He received his B.S. degree in 1992 and The Trust, which is administered by the Financial his M.S. degree in 1994, both from the University of Melbourne. He recently received his Ph.D. from the University Management and Trust Services Division of Boone County of California at Berkeley, where he wrote a dissertation National Bank in Columbia, Missouri, pays its net income solving a long-standing open problem in the area of braid to the recipient of the award each year for four years. An groups. -

Child of Vietnam War Wins Top Maths Honour 19 August 2010, by P.S

Child of Vietnam war wins top maths honour 19 August 2010, by P.S. Jayaram Vietnamese-born mathematician Ngo Bao Chau Presented every four years to two, three, or four on Thursday won the maths world's version of a mathematicians -- who must be under 40 years of Nobel Prize, the Fields Medal, cementing a journey age -- the medal comes with a cash prize of 15,000 that has taken him from war-torn Hanoi to the Canadian dollars (14,600 US dollars). pages of Time magazine. The only son of a physicist father and a mother who Ngo, 38, was awarded his medal in a ceremony at was a medical doctor, Ngo's mathematical abilities the International Congress of Mathematicians won him a place, aged 15, in a specialist class of meeting in the southern Indian city of Hyderabad. the Vietnam National University High School. The other three recipients were Israeli In 1988, he won a gold medal at the 29th mathematician Elon Lindenstrauss, Frenchman International Mathematical Olympiad and repeated Cedric Villani and Swiss-based Russian Stanislav the same feat the following year. Smirnov. After high school, he was offered a scholarship by Ngo, who was born in Hanoi in 1972 in the waning the French government to study in Paris. He years of the Vietnam war, was cited for his "brilliant obtained a PhD from the Universite Paris-Sud in proof" of a 30-year-old mathematical conundrum 1997 and became a professor there in 2005. known as the Fundamental Lemma. Earlier this year he became a naturalised French The proof offered a key stepping stone to citizen and accepted a professorship at the establishing and exploring a revolutionary theory University of Chicago. -

2004 Research Fellows

I Institute News 2004 Research Fellows On February 23, 2004, the Clay Mathematics Institute announced the appointment of four Research Fellows: Ciprian Manolescu and Maryam Mirzakhani of Harvard University, and András Vasy and Akshay Venkatesh of MIT. These outstanding mathematicians were selected for their research achievements and their potential to make signifi cant future contributions. Ci ian Man lescu 1 a nati e R mania is c m letin his h at Ha a ni Ciprian Manolescu pr o (b. 978), v of o , o p g P .D. rv rd U - versity under the direction of Peter B. Kronheimer. In his undergraduate thesis he gave an elegant new construction of Seiberg-Witten Floer homology, and in his Ph.D. thesis he gave a remarkable gluing formula for the Bauer-Furuta invariants of four-manifolds. His research interests span the areas of gauge theory, low-dimensional topology, symplectic geometry and algebraic topology. Manolescu will begin his four-year appointment as a Research Fellow at Princeton University beginning July 1, 2004. Maryam Mirzakhani Maryam Mirzakhani (b. 1977), a native of Iran, is completing her Ph.D. at Harvard under the direction of Curtis T. McMullen. In her thesis she showed how to compute the Weil- Petersson volume of the moduli space of bordered Riemann surfaces. Her research interests include Teichmuller theory, hyperbolic geometry, ergodic theory and symplectic geometry. As a high school student, Mirzakhani entered and won the International Mathematical Olympiad on two occasions (in 1994 and 1995). Mirzakhani will conduct her research at Princeton University at the start of her four-year appointment as a Research Fellow beginning July 1, 2004. -

ISRAEL MATTERS! MATTERS! Publication of the Israel Affairs Committee of Temple Beth Sholom

ISRAELISRAEL MATTERS! MATTERS! Publication of the Israel Affairs Committee of Temple Beth Sholom Issue Number 40 October 2010 Israel Begins Peace Negotiations; Demands Palestinians Recognize Israel as Jewish State In remarks at the September relaunch of peace negotiations, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu opened by saying, “I began with a Hebrew word for peace, “shalom.” Our goal is shalom. Our goal is to forge a secure and durable peace between Israelis and Palestinians. We don’t seek a brief interlude between two wars. We don’t seek a tempo- rary respite between outbursts of terror. We seek a peace that will end the conflict between us once and for all. We seek a peace that will last for generations -- our generation, our children’s generation, and the next.” Continuing, he said, “… a defensible peace requires security arrangements that can withstand the test of time and the many chal- lenges that are sure to confront us. … Let us not get bogged down by every dif- ference between us. Let us direct our courage, our thinking, and our decisions at those historic decisions that lie ahead.” Concluding, Netanyahu said, “President Abbas, we cannot erase the past, but it is within our power to change the future. Thousands of years ago, on these very hills where Israelis and Palestinians live today, the Jewish prophet Isaiah and the other prophets of my people envisaged a future of lasting peace for all mankind. Let today be an auspicious step in our joint effort to realize that ancient vision for a better future.” Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, left, Against that background, Netanyahu has maintained the fundamental demand and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, right, at that the Palestinians must recognize Israel as a Jewish state in his remarks the opening session of peace talks hosted by US secretary of state Hillary Clinton. -

Random Walks on Locally Homogeneous Spaces

RANDOM WALKS ON LOCALLY HOMOGENEOUS SPACES ALEX ESKIN AND ELON LINDENSTRAUSS Dedicated to the memory of Maryam Mirzakhani Abstract. Let G be real Lie group, and Γ a discrete subgroup of G. Let µ be a measure on G. Under a certain condition on µ, we classify the finite µ-stationary measures on G=Γ. We give an alternative argument (which bypasses the Local Limit Theorem) for some of the breakthrough results of Benoist and Quint in this area. Contents 1. Introduction1 2. General cocycle lemmas 15 3. The inert subspaces Ej(x) 30 4. Preliminary divergence estimates 37 5. The action of the cocycle on E 39 6. Bounded subspaces and synchronized exponents 44 7. Bilipshitz estimates 62 8. Conditional measures. 64 9. Equivalence relations on W + 67 10. The Eight Points 68 11. Case II 84 12. Proof of Theorem 1.2. 101 References 106 Index of Notation 109 1. Introduction 1.1. Random walks and stationary measures. Let G0 be a real algebraic Lie Group, let g0 denote the Lie algebra of G0, and let Γ0 be a discrete subgroup of G0. Let µ be a probablity measure on G0 with finite first moment. Let ν be an µ-stationary Research of the first author is partially supported by NSF grants DMS 1201422, DMS 1500702 and the Simons Foundation. Research of the second author is partially supported by the ISF (891/15). 1 2 ALEX ESKIN AND ELON LINDENSTRAUSS measure on G0=Γ0, i.e. Z µ ν = ν; where µ ν = gν dµ(g). ∗ ∗ G0 We assume ν(G0=Γ0) = 1, and also that ν is ergodic (i.e. -

From Rational Billiards to Dynamics on Moduli Spaces

FROM RATIONAL BILLIARDS TO DYNAMICS ON MODULI SPACES ALEX WRIGHT Abstract. This short expository note gives an elementary intro- duction to the study of dynamics on certain moduli spaces, and in particular the recent breakthrough result of Eskin, Mirzakhani, and Mohammadi. We also discuss the context and applications of this result, and connections to other areas of mathematics such as algebraic geometry, Teichm¨ullertheory, and ergodic theory on homogeneous spaces. Contents 1. Rational billiards 1 2. Translation surfaces 3 3. The GL(2; R) action 7 4. Renormalization 9 5. Eskin-Mirzakhani-Mohammadi's breakthrough 10 6. Applications of Eskin-Mirzakhani-Mohammadi's Theorem 11 7. Context from homogeneous spaces 12 8. The structure of the proof 14 9. Relation to Teichm¨ullertheory and algebraic geometry 15 10. What to read next 17 References 17 1. Rational billiards Consider a point bouncing around in a polygon. Away from the edges, the point moves at unit speed. At the edges, the point bounces according to the usual rule that angle of incidence equals angle of re- flection. If the point hits a vertex, it stops moving. The path of the point is called a billiard trajectory. The study of billiard trajectories is a basic problem in dynamical systems and arises naturally in physics. For example, consider two points of different masses moving on a interval, making elastic collisions 2 WRIGHT with each other and with the endpoints. This system can be modeled by billiard trajectories in a right angled triangle [MT02]. A rational polygon is a polygon all of whose angles are rational mul- tiples of π. -

Invariant Measures and Arithmetic Unique Ergodicity

Annals of Mathematics, 163 (2006), 165–219 Invariant measures and arithmetic quantum unique ergodicity By Elon Lindenstrauss* Appendix with D. Rudolph Abstract We classify measures on the locally homogeneous space Γ\ SL(2, R) × L which are invariant and have positive entropy under the diagonal subgroup of SL(2, R) and recurrent under L. This classification can be used to show arithmetic quantum unique ergodicity for compact arithmetic surfaces, and a similar but slightly weaker result for the finite volume case. Other applications are also presented. In the appendix, joint with D. Rudolph, we present a maximal ergodic theorem, related to a theorem of Hurewicz, which is used in theproofofthe main result. 1. Introduction We recall that the group L is S-algebraic if it is a finite product of algebraic groups over R, C,orQp, where S stands for the set of fields that appear in this product. An S-algebraic homogeneous space is the quotient of an S-algebraic group by a compact subgroup. Let L be an S-algebraic group, K a compact subgroup of L, G = SL(2, R) × L and Γ a discrete subgroup of G (for example, Γ can be a lattice of G), and consider the quotient X =Γ\G/K. The diagonal subgroup et 0 A = : t ∈ R ⊂ SL(2, R) 0 e−t acts on X by right translation. In this paper we wish to study probablilty measures µ on X invariant under this action. Without further restrictions, one does not expect any meaningful classi- fication of such measures. For example, one may take L = SL(2, Qp), K = *The author acknowledges support of NSF grant DMS-0196124. -

MATHEMATICS Catalogue7

2 0 1 MATHEMATICS Catalogue7 Connecting Great Minds HighlightsHighlights Mathematics Catalogue 2017 page 5 page 6 page 8 page 9 by Tianxin Cai by Jean-Pierre Tignol by E Jack Chen by Michel Marie Chipot (Zhejiang University, China) & (Université Catholique de Louvain, (BASF Corporation, USA) (University of Zurich, Switzerland) translated by Jiu Ding Belgium) (University of Southern Mississippi, USA) page 12 page 13 page 15 page 18 by Shaun Bullett by Sir Michael Atiyah (University of by Yi-Bing Shen (Zhejiang University, by Niels Jacob & Kristian P Evans (Queen Mary University of Edinburgh, UK), Daniel Iagolnitzer China) & Zhongmin Shen (Swansea University, UK) London, UK), (CEA-Saclay, France) & Chitat Chong (Indiana University – Purdue University Tom Fearn & Frank Smith (NUS, Singapore) Indianapolis, USA) (University College London, UK) page 19 page 20 page 24 page 24 by Gregory Baker by Michał Walicki by Kai S Lam (California State by Matthew Inglis & Nina Attridge (The Ohio State University, USA) (University of Bergen, Norway) Polytechnic University, Pomona, USA) (Loughborough University, UK) page 27 page 27 page 30 page 31 by Roe W Goodman by Gregory Fasshauer by Jiming Jiang (UC Davis) & by Paulo Ribenboim (Rutgers University, USA) (Illinois Institute of Technology, USA) & Thuan Nguyen (Queen's University, Canada) Michael McCourt (Oregon Health & Science (University of Colorado Denver, USA) University, USA) c o n t e n t s About World Scientific Publishing World Scientific Publishing is a leading independent publisher of books and journals for the scholarly, research, professional and educational communities. The company publishes about 600 books annually and about 130 Algebra & Number Theory .................................. -

From Rational Billiards to Dynamics on Moduli Spaces

FROM RATIONAL BILLIARDS TO DYNAMICS ON MODULI SPACES ALEX WRIGHT Abstract. This short expository note gives an elementary intro- duction to the study of dynamics on certain moduli spaces, and in particular the recent breakthrough result of Eskin, Mirzakhani, and Mohammadi. We also discuss the context and applications of this result, and connections to other areas of mathematics such as algebraic geometry, Teichm¨ullertheory, and ergodic theory on homogeneous spaces. Contents 1. Rational billiards 1 2. Translation surfaces 3 3. The GL(2; R) action 7 4. Renormalization 9 5. Eskin-Mirzakhani-Mohammadi's breakthrough 10 6. Applications of Eskin-Mirzakhani-Mohammadi's Theorem 11 7. Context from homogeneous spaces 12 8. The structure of the proof 14 9. Relation to Teichm¨ullertheory and algebraic geometry 15 10. What to read next 17 References 17 arXiv:1504.08290v2 [math.DS] 26 Jul 2015 1. Rational billiards Consider a point bouncing around in a polygon. Away from the edges, the point moves at unit speed. At the edges, the point bounces according to the usual rule that angle of incidence equals angle of re- flection. If the point hits a vertex, it stops moving. The path of the point is called a billiard trajectory. The study of billiard trajectories is a basic problem in dynamical systems and arises naturally in physics. For example, consider two points of different masses moving on a interval, making elastic collisions 2 WRIGHT with each other and with the endpoints. This system can be modeled by billiard trajectories in a right angled triangle [MT02]. A rational polygon is a polygon all of whose angles are rational mul- tiples of π. -

Furstenberg and Margulis Awarded 2020 Abel Prize

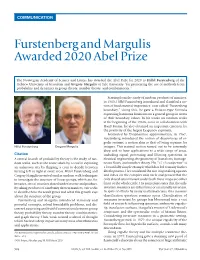

COMMUNICATION Furstenberg and Margulis Awarded 2020 Abel Prize The Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters has awarded the Abel Prize for 2020 to Hillel Furstenberg of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Gregory Margulis of Yale University “for pioneering the use of methods from probability and dynamics in group theory, number theory, and combinatorics.” Starting from the study of random products of matrices, in 1963, Hillel Furstenberg introduced and classified a no- tion of fundamental importance, now called “Furstenberg boundary.” Using this, he gave a Poisson-type formula expressing harmonic functions on a general group in terms of their boundary values. In his works on random walks at the beginning of the 1960s, some in collaboration with Harry Kesten, he also obtained an important criterion for the positivity of the largest Lyapunov exponent. Motivated by Diophantine approximation, in 1967, Furstenberg introduced the notion of disjointness of er- godic systems, a notion akin to that of being coprime for Hillel Furstenberg Gregory Margulis integers. This natural notion turned out to be extremely deep and to have applications to a wide range of areas, Citation including signal processing and filtering questions in A central branch of probability theory is the study of ran- electrical engineering, the geometry of fractal sets, homoge- dom walks, such as the route taken by a tourist exploring neous flows, and number theory. His “×2 ×3 conjecture” is an unknown city by flipping a coin to decide between a beautifully simple example which has led to many further turning left or right at every cross. Hillel Furstenberg and developments.