Thesis-1992D-M234y.Pdf (6.002Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

1435 2012 ^ Five Dollar 435

BLACK RADIO - CLUSIVE BLACK ENTERTAINMENT'S PR '' 36YEARS ISSN in-1435 2012 ^ FIVE DOLLAR 435 o 'I-47 3500 4 Featuring the final recorded performances from the late music icon WHITNEY HOUSTON _LtBRATE ORIGINAL N^mON pirTI IPF SOUNDTRACK FEATURING NEW MUSIC FROM JORDIN SPARKSAND WHITNEY HOUSTON ON THE URBAN ADULT RADIO HIT PRODUCED BY R. KELLY "CELEBRATE" AND A SOUL -STIRRING RENDITION OF WHITNEY HOUSTON ON "Li le Mir IC cM TUC QPAPDOW" 13 -SONG SOUNDTRACK ALSO INCLUDES CEE LO GREEN ON "I'M A MAN," GOAPELE ON "RUNNING," AND CARMEN EJOGO AND TIKA SUMPTER JOINING JORDIN SPARKS ON "SOMETHING HE CAN FEEL" WITH THREE NEW SONGS BY JORDIN SPARKS AVAILABLE EVERYWHERE JULY 31 ON it,14 RECORDS/SONY MUSIC From the Movie Directed by SALIM AKIL in Theaters Nationwide AUGUST 17TH The state of magazines is sticky, 43 minutes per issue sticky. Media continues to proliferate. ',Attention spans continue to shrink. And free content is available everywhere, from the Internet to the insides of elevators. Why then are 93% of American adults still so attached to magazines? Why do so many people, young and old, spend so much time with a medium that's paper and ink, a medium you actually have to pay for in order to read? In a word, engagement. Reading a magazine remains a uniquely intimate and immersive experience. Not only is magazine readership up, readers spend an average of 43 minutes per issue. Further, those 43 minutes of attention are typically undivided. Among all media-digital or analog-magazine readers are least likely to engage in another activity while reading. -

Media Culture: Cultural Studies, Identity and Politics Between The

Media Culture Media Culture develops methods and analyses of contemporary film, television, music, and other artifacts to discern their nature and effects. The book argues that media culture is now the dominant form of culture which socializes us and provides materials for identity in terms of both social reproduction and change. Through studies of Reagan and Rambo, horror films and youth films, rap music and African- American culture, Madonna, fashion, television news and entertainment, MTV, Beavis and Butt-Head, the Gulf War as cultural text, cyberpunk fiction and postmodern theory, Kellner provides a series of lively studies that both illuminate contemporary culture and provide methods of analysis and critique. Many people today talk about cultural studies, but Kellner actually does it, carrying through a unique mixture of theoretical analysis and concrete discussions of some of the most popular and influential forms of contemporary media culture. Criticizing social context, political struggle, and the system of cultural production, Kellner develops a multidimensional approach to cultural studies that broadens the field and opens it to a variety of disciplines. He also provides new approaches to the vexed question of the effects of culture and offers new perspectives for cultural studies. Anyone interested in the nature and effects of contemporary society and culture should read this book. Kellner argues that we are in a state of transition between the modern era and a new postmodern era and that media culture offers a privileged field of study and one that is vital if we are to grasp the full import of the changes currently shaking us. -

UA19/17/1 Hilltopper Football 1984

• ., Index 1984 Hilltopper Schedule • Western 08111 ~ SiI.(Tme.~ ..... Sept. 8 AppalllChian Slale ................. SmithStldium(I:OOp.m.j Kentucky ~., 15 al Akron . ........... ....... .. ...... AkIon.()Jio(6:30 p.m.) 1. ,. 0 22 Central Florida _.• _M. __.. Smith Stadium (1:00 p.m.) AIlS- 3- 2 >~O -- Hilltoppers 29 al Southeastern l.o\.lsIana .......... Hammond, La.(7:OOp.m.) "'"., ~ ~. Oct. 6 all.ouiM1e ............................... L.ouisviDe, Ky.(6:OOp.m.) . 51.1· 0- 0 locallOrt' 9:Iege HeiIjlIs >" 12·12· 0 ~Green,K P IOI 13 Southwest Missouri ............ M SmllhStadium(I:OOp.m.) ~>. Fourldtd' 1906 .. 20 Eastern Kentucky ...........••..••. SmUhStadlu m(I :00 p.m.) ~~. 7· 3- 1 Wk34-2I). 3 Ermrrnent: 12,666 27 al Morehead Slate ................... Morehead, Ky.(12:30p.m.) 2· 9- 0 WK33- 7. 2 Pfeso.r.; Or. Donald W Zarhlnas Nov. 3 Middle Tenne.we .••.•~.M .... M. SmithStadium(I:00p.m., 8- 2· 0 Wk 25-24- , 55 Held Coactr: Dave Roberts (Homec;omlng) 25 .cfna 'rIater: Western Carolfla 'fie 10 .1 Eastern IIioots _.......... _.......... OIarIeslon," (1:00 p.m.) 9- 2· 0 Ell· 0- 0 . 23 ~ Record: IisI year 17 al Mun.y State ......... ........ Mooay, Ky.( I:30p.m.) 7· 4- 0 W!(24.2I). 6 ~.:aI W){U: Ii.,.r ... I•S- orr.ce etow (502) 745-2984 ...... 3t Best Trme to CaD; Morrungs --_T' ........... ~101 a es. 88 """,.. Don Powers (WeSlem Carolrna 67 103·t07 Butdl Gllbi!l'1 rWKU 52) 1983 Results 17 David CuIey (VNderbiIt 71) 2 Record: 2-8-1 (home 2·3-0; away 0.5-1) Sieve Shanlo. .... ~ rOaVKlson 74) . -

The Ithacan, 1997-04-17

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1996-97 The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 4-17-1997 The thI acan, 1997-04-17 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1996-97 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 1997-04-17" (1997). The Ithacan, 1996-97. 25. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1996-97/25 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1990/91 to 1999/2000 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1996-97 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Opznzon AccenT SpOR.TS In~ex Changes Class Art Accent ........................ 13 Teeing Off Classifieds .................. 21 New president has Seniors show their Ithaca area is a Comics ........................ 22 chance to redefine best at the sand trap for Opinion ...................... 10 the College 10 Handwerker exhibit 13 golfers 23 Sports ........................ 23 The IT The Newspaper for the Ithaca College Community VOLUME 64, NUMBER 26 THURSDAY, APRIL 17, 1997 28 PAGES, FREE SENIOR SHOWCASE Investigation comes to end Student misses court date felony gambling charge to By Ryan Lillis and involve more than five bets in Andrew Tutino excess of $5,000. Alton was orig Ithacan Staff inally scheduled to appear for The second student charged in arraignment April 9; however, he connection with the gambling was granted an adjournment until investigation at Ithaca College Wednesday. Alton's attorney, failed to appear before Judge William McCloski, of Adams, Raymond Bordoni Wednesday N.Y., said he attempted lo sched night in Ithaca Town Court. -

112 Cupid 311 All I Want Is You 311 All Mixed

SING - DIE KARAOKESHOW 112 Cupid 311 All I Want Is You 311 All Mixed up 311 Hey You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 That's When I Think Of You 1975 Give Yourself A Try 1975 TootimeTootimeTootime 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I´m Mandy 10cc I´m Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 12 Stones We Are One 18 Days Saving Abel 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1975, The Chocolate 1975, The City, The 1975, The Love Me 1975, The Robbers 1975, The Sex 1975, The Somebody Else 1975, The Sound, The 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 AM Club Not Your Boyfriend 2 Evisa Oh La La 2 Live Crew Doo Wah Diddy 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Pac feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limits 21 Savage feat. Offset, Metro Boomin & … Ghostface Killers 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Degrees, The Woman In Love 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Every Time You Go 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It´s Not My Time 3 Doors Down Krytonite 3 Doors Down Road I´m On, The 3 Doors Down Train 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Walk On Water 35L Take It Easy www.sing-diekaraokeshow.de SING - DIE KARAOKESHOW 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 3OH!3 Double Vision 3OH!3 Starstrukk 3OH!3 & Neon Hitch Follow Me Down 3OH!3 feat. -

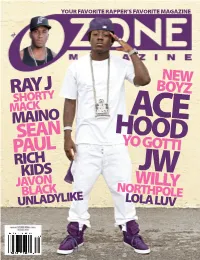

Ray J Sean Paul

YOUR FAVORITE RAPPER’S FAVORITE MAGAZINE OZONE MAGAZINE WE WORK NIGHTS,WE SOMEVAMPIRES / GATHER ROUNDTHE BEAT LIKE A CAMPFIRE ISSUE #78 NEW BOYZ RAY J SHORTY MACK ACE MAINO HOOD SEAN YO GOTTI PAUL RICH JW KIDS WILLY JAVON NORTHPOLE BLACK LOLA LUV UNLADYLIKE 1 OZONE MAG // YOURYOUR FAVORITEFAVORITE RAPPER’SRAPPER’S FAVORITEFAVORITE MAGAZINEMAGAZINE KNOCKOKNOCKOUUTT ENTERTAINMENT’sENTERTAINMENT’s SHORTYSHORTY MACKMACK && RAYRAY JJ ACE HOOD MAINO NEW BOYZ SEAN PAUL YO GOTTI RICH KIDS WILL Y JAVON BLACK NORTHPOLE UNLADYLIKE LOLA LUV 20 // OZONE MAG 2 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 3 4 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 5 6 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 7 8 // OZONE MAG OZONE MAG // 9 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF // Julia Beverly MUSIC EDITOR // Randy Roper FEATURES EDITOR // Eric N. Perrin cover stories ASSOCIATE EDITOR // Maurice G. Garland GRAPHIC DESIGNER // David KA 42-43 ACE HOOD ADVERTISING SALES // Che Johnson, Gary Archer 54-58 RAY J & SHORTY MACK PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR // Malik Abdul W12-W13 WILLY NORTHPOLE SPECIAL EDITION EDITOR // Jen McKinnon WEST COAST EDITOR-AT-LARGE // D-Ray LEGAL CONSULTANT // Kyle P. King, P.A. SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER // Adero Dawson ADMINISTRATIVE // Kisha Smith INTERNS // Devon Buckner, Jee’Van Brown, Krystal Moody, Memory Martin, Ms Ja, Shanice Jarmon, Torrey Holmes CONTRIBUTORS // Anthony Roberts, Bogan, Camilo Smith, Charlamagne the God, Chuck T, Cierra Middlebrooks, David Rosario, Diwang Valdez, DJ BackSide, Edward Hall, E-Z Cutt, Gary Archer, Hannibal Matthews, Jacquie Holmes, J Lash, Jason Cordes, Jelani Harper, Joey Colombo, Johnny Louis, Kay Newell, Keadron Smith, Keita Jones, Keith Kennedy, K.G. Mosley, King Yella, Luis Santana, Luvva J, Luxury Mindz, Marcus DeWayne, Matt Sonzala, Maurice G. -

Black CEO Awards Nonprofit Grants

Volume 97 Number 39 | MAY 13-19, 2020 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents Obama’s com- Former President Barack Obama ments came during on Trump’s handling of cororavirus a Friday call with 3,000 members of KEVIN FREKING the Obama Alumni Associated Press Association, people who served in his ad- ASHINGTON — Former President Barack Obama harshly criticized Pres- ministration. Obama ident Donald Trump’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic as an “ab- urged his supporters solute chaotic disaster” during a conversation with ex-members of his to back his former administration, according to a recording obtained by Yahoo News. vice president, Joe Biden, who is trying W to unseat Trump in Obama also reacted to the Justice De- istration. Obama urged his supporters to the Nov. 3 election. partment dropping its criminal case against back his former vice president, Joe Biden, Trump’s first national security adviser, who is trying to unseat Trump in the Nov. 3 Michael Flynn, saying he worried that the election. “basic understanding of rule of law is at “What we’re fighting against is these risk.” long-term trends in which being More than 78,400 people with COVID-19 selfish, being tribal, being divided, have died in the United States and more and seeing others as an enemy than 1.3 million people have tested — that has become a stronger positive, according to the latest impulse in American life. And estimates from the Center for by the way, we’re seeing that Systems Science and Engi- internationally as well. It’s neering at Johns Hopkins part of the reason why the University. -

All-Star 2007 **Special Edition**

ALL-STAR 2007 **SPECIAL EDITION** THREE 6 MAFIA \\ MISTAH FAB +TOO $HORT \\ BIG FASE \\ WEASE lil’FLIP X1 \\ J-DIGGS \\ MAC MALL ALL-STAR 2007 **SPECIAL EDITION** three mafia LIL FLIP \\ TOO $HORT \\ MISTAH FAB \\ MAC6 MALL \\ BIG FASE \\ WEASE +\\ X1 \\ J-DIGGS ALL-STAR 2007 PUBLISHER: Julia Beverly CONTRIBUTORS: D-Ray Ms. Rivercity N. Ali Early o ADVERTISING SALES: Che Johnson PROMOTIONS DIRECTOR: Malik Abdul ART DIRECTOR: Tene Gooden SUBSCRIPTIONS: To subscribe, send check or money order for $11 to: Ozone Magazine 644 Antone St. Suite 6 Atlanta, GA 30318 Phone: 404-350-3887 Fax: 404-350-2497 Web: www.ozonemag.com COVER CREDITS: SECTION A Lil Flip photo by Mike Frost; 12 DJ Drop Three 6 Mafia photo provided 13 Pics1 by Sony; DJ Juice & Mistah FAB 15 DJ warren peace photos by Julia Beverly. 17 DJ slimm 19 DJ franzen DISCLAIMER: 21 Vegas map OZONE does not take 22 All Star event listing 24 Vegas club listing responsibility for unsolicited 25 Vegas club listing materials, misinformation, 26 too short’S guide to vegas typographical errors, or misprints. The views contained herein do not necessarily 28-31 LIL FLIP reflect those of the publisher 34 mistah fab or its advertisers. Ads appear- 38 mac mall ing in this magazine are not an endorsement or valida- tion by OZONE Magazine for products or services offered. All photos and illustrations are SECTION B copyrighted by their respec- 11 pics tive artists. All other content 12 DJ Big Dee is copyright 2007 OZONE 14 DJ RorY MacK Magazine, all rights reserved. -

Hip-Hop Futurism: Remixing Afrofuturism and the Hermeneutics of Identity Chuck Galli Rhode Island College, [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 4-2009 Hip-Hop Futurism: Remixing Afrofuturism and the Hermeneutics of Identity Chuck Galli Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the African American Studies Commons, Other Music Commons, and the Personality and Social Contexts Commons Recommended Citation Galli, Chuck, "Hip-Hop Futurism: Remixing Afrofuturism and the Hermeneutics of Identity" (2009). Honors Projects Overview. 18. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/18 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP FUTURISM: REMIXING AFROFUTURISM AND THE HERMENEUTICS OF IDENTITY By Chuck Galli An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in The Program in African and African-American Studies Faculty of Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2009 Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction 6 Chapter 1 – Hip-Hop: The Beginning 11 Chapter 2 – Afrofuturism 26 Chapter 3 – Hip-Hop’s Modes of Production as Futuristic 37 Chapter 4 – Hip-Hop Futurism 71 Chapter 5 – Hip-Hop Futurism’s Implications for Life on Earth 108 Appendices 115 Bibliography 128 Acknowledgements 131 1 Preface Before I introduce this thesis, there are a number of concepts which need to be defined and stylistic points which need to be explained. I feel it is better to address them right from the beginning than try to suavely weave them into the main body of the paper. -

January 1997

Decades apart in age, Roy Haynes and Lewis Nash nonetheless share the vision, taste, and work ethic that keep jazz drumming at a phenomenally high artistic level. Two luminaries shed light on the history—and future—of Swingin'. by Ken Micallef 44 Twinkie.. .granola., .Twinkie,. .granola, Among musicians who plow the dark If you plan on cutting just about any gig depths of metal/industrial hybrids, these days, you better be making the right Prong is often cited as the style's choices for a healthy drumming career. This galvanizing force, Drummer Ted Parsons exclusive MD story takes a realistic look at and his gang might not get the atten- keeping in shape behind the kit, including tion they deserve, but they're still push- the exercises every drummer should know. ing the envelope—hard. by Mark Scholl by Matt Peiken 70 86 photo by Paul La Raia Volume 21 Number 1 Cover photo Paul La Raia education equipment 104 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC 30 NEW AND NOTABLE Developing A Strong Groove With A Good Feel 36 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP by Will Kennedy New Paiste Cymbals And Sounds by Rick Van Horn 106 ROCK CHARTS Raymond Weber: 40 Drum Workshop P-Series Pedals "How Do Ya'11 Know" And 9100 Throne Transcribed by Vincent DeFrancesco by Rick Van Horn 112 THE JOBBING DRUMMER 140 COLLECTORS' CORNER Playing For Ballroom Dancing Leedy (Chicago) by Russ Lewellen Shelly Manne Model Snare by Harry Cangany 116 STRICTLY TECHNIQUE An Accent Challenge by Frank Michael news 138 DRUM COUNTRY 10 UPDATE Steve Gorman of the Black Crowes, Blessid Union Of Souls' Sharing A Drumkit Eddie -

District Gives Instructional Tech Update Monthly Work Session

LOCAL FOOTBALL Sumter Touchdown Club honors high school Players WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2020 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 $1.00 of the Week B1 District gives instructional tech update monthly work session. students as an upgrade to the many as four to five electronic 4 weeks into virtual learning model, Sumter Nobody could have forecast- traditional online learning devices in use at a single time ed where K-12 education na- that took place in the spring. at their desk area while con- administrators discuss supports to teachers tionwide would be currently, It hasn’t been without some ducting virtual instruction to given the COVID-19 pandemic. hiccups thus far, district lead- maximize student learning. BY BRUCE MILLS room teachers. In mid-March with the initial ers said, but staff and admin- Laws described it as a “bap- [email protected] District Director of Instruc- spread of the virus in the U.S., istration are trying to provide tism by fire” to a certain ex- tional Technology David public and private schools the necessary resources to tent for classroom teachers After four weeks of virtual Laws, the district’s two in- across the state and nation teachers, who are leading the and also for district adminis- learning to start the school structional technology spe- closed their doors to in-person educational process from tration with the new technolo- year, Sumter School District cialists and other administra- instruction. their individual school class- gy. administrators provided the tors led a 55-minute presenta- With the start of the fall rooms.