Britain's Cosmopolitan Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autumn Statement 2012: Reaction

Autumn Statement 2012: Reaction This Library Note provides a brief summary of the key measures announced yesterday in the Chancellor’s Autumn Statement, before outlining the immediate reaction to the Statement as expressed by the Shadow Chancellor in the House of Commons and by a range of organisations and commentators. Ian Cruse Sarah Tudor 6 December 2012 LLN 2012/042 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 2. Autumn Statement ....................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Projections for Growth and Public Finances ........................................................... 1 2.2 Public Spending ..................................................................................................... 2 2.3 Investment and Infrastructure ................................................................................ 2 2.4 Measures Relating to Tax -

30 March 2012 Page 1 of 17

Radio 4 Listings for 24 – 30 March 2012 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 24 MARCH 2012 SAT 06:57 Weather (b01dc94s) The Scotland Bill is currently progressing through the House of The latest weather forecast. Lords, but is it going to stop independence in its tracks? Lord SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b01dc948) Forsyth Conservative says it's unlikely Liberal Democrat Lord The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Steel thinks it will. Followed by Weather. SAT 07:00 Today (b01dtd56) With John Humphrys and James Naughtie. Including Yesterday The Editor is Marie Jessel in Parliament, Sports Desk, Weather and Thought for the Day. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b01dnn41) Tim Winton: Land's Edge - A Coastal Memoir SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (b01dtd5j) SAT 09:00 Saturday Live (b01dtd58) Afghans enjoy New Year celebrations but Lyse Doucet finds Episode 5 Mark Miodownik, Luke Wright, literacy champion Sue they are concerned about what the months ahead may bring Chapman, saved by a Labradoodle, Chas Hodges Daytrip, Sarah by Tim Winton. Millican John James travels to the west African state of Guinea-Bissau and finds unexpected charms amidst its shadows In a specially-commissioned coda, the acclaimed author Richard Coles with materials scientist Professor Mark describes how the increasingly threatened and fragile marine Miodownik, poet Luke Wright, Sue Chapman who learned to The Burmese are finding out that recent reforms in their ecology has turned him into an environmental campaigner in read and write in her sixties, Maurice Holder whose life was country have encouraged tourists to return. -

Challenging the Whiteness of Britishness: Co-Creating British Social History in the Blogosphere

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – September 2015 Challenging the Whiteness of Britishness: Co-Creating British Social History in the Blogosphere Deborah Gabriel, Bournemouth University, UK Abstract Blogs are a valuable medium for preserving cultural memory, reflecting the various dimensions of human life (O’Sullivan, 2005) and allowing ordinary individuals and marginalised groups the opportunity to contribute to the ‘dialogue of history’ (Cohen, 2005:10). The diverse perspectives to be found in the blogosphere can help deepen understanding of historical moments. Such examples include 9/11 (Cohen, 2005), the London bombings in 2005 (Allan, 2006) and Hurricane Katrina (Brock, 2009). Using critical race theory (CRT) as a theoretical framework and cultural democracy as the conceptual framework, this study examines the symbolic power of counter-storytelling through the blogosphere. The findings reveal that in relation to coverage of the UK ‘riots’ in 2011 and the Stephen Lawrence verdict in 2012, African Caribbean bloggers advanced alternative perspectives of the events and appropriated blogs as a medium for self-representation through their own constructions of Black identity. In so doing they performed a vital role as co- creators of British social history. 1 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – September 2015 Introduction Historical archives in Britain often exclude or fail to capture the presence and experiences of people of colour (which dates back to the 17th century with the first arrival of slaves from the west coast of Africa), resulting in a ‘whitenening of Britishness’ Bressey (2006:51). The term is defined as a process through which the exclusion of a person’s skin colour in historical records results in the assumption of a white identity (Bressey, 2006). -

Tory Modernisation 2.0 Tory Modernisation

Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg Guy and Shorthouse Ryan by Edited TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 MODERNISATION TORY edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 THE FUTURE OF THE CONSERVATIVE PARTY TORY MODERNISATION 2.0 The future of the Conservative Party Edited by Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg The moral right of the authors has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a re- trieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. Bright Blue is an independent, not-for-profit organisation which cam- paigns for the Conservative Party to implement liberal and progressive policies that draw on Conservative traditions of community, entre- preneurialism, responsibility, liberty and fairness. First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Bright Blue Campaign www.brightblue.org.uk ISBN: 978-1-911128-00-7 Copyright © Bright Blue Campaign, 2013 Printed and bound by DG3 Designed by Soapbox, www.soapbox.co.uk Contents Acknowledgements 1 Foreword 2 Rt Hon Francis Maude MP Introduction 5 Ryan Shorthouse and Guy Stagg 1 Last chance saloon 12 The history and future of Tory modernisation Matthew d’Ancona 2 Beyond bare-earth Conservatism 25 The future of the British economy Rt Hon David Willetts MP 3 What’s wrong with the Tory party? 36 And why hasn’t -

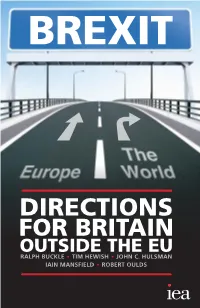

Directions for Britain Outside the Eu Ralph Buckle • Tim Hewish • John C

BREXIT DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE • TIM HEWISH • JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD • ROBERT OULDS BREXIT: Directions for Britain Outside the EU BREXIT: DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE TIM HEWISH JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD ROBERT OULDS First published in Great Britain in 2015 by The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London SW1P 3LB in association with London Publishing Partnership Ltd www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2015 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-255-36682-3 (interactive PDF) Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Director General at the address above. Typeset in Kepler by T&T Productions Ltd www.tandtproductions.com -

Audience Attitudes to the Licence Fee and Public Service Broadcasting Provision Beyond the BBC

Audience attitudes to the licence fee and public service broadcasting provision beyond the BBC A report by Human Capital Based on data collected by Ipsos MORI and the Knowledge Agency December 2008 Audience attitudes to the licence fee and public service broadcasting beyond the BBC: A report by Human Capital, December 2008 Contents 1 Executive summary ..........................................................................................3 2 Introduction.....................................................................................................13 3 The licence fee research ................................................................................16 4 Future priorities and willingness to pay for PSB on commercially funded PSBs .......................................................................................................................36 2 Audience attitudes to the licence fee and public service broadcasting beyond the BBC: A report by Human Capital, December 2008 1 Executive summary 1.1 Introduction This report sets out the audience research commissioned by the BBC to inform its submission to Ofcom as part of Phase 2 of the Second Review into Public Service Broadcasting (PSB). Human Capital, an independent media consultancy, was commissioned to analyse and draw together all strands of research, including data collected by Ipsos MORI and the Knowledge Agency as part of the BBC’s Phase 2 response to this Review. Building on a large body of existing evidence around PSB, this research focused specifically on two -

Redeeming the “Ordinary Working Class” Robbie Shilliam

Redeeming the “Ordinary Working Class” Robbie Shilliam Forthcoming – Current Sociology (2020) Introduction In describing for the Sunday Telegraph what she envisaged to be Britain’s post-EU “shared society”, Prime Minister Theresa May (2017) explicitly placed the “ordinary working class” as its prime deserving constituency. May’s address, while not providing a sociological definition, nonetheless gave a clear sense of what, to her, counted as “ordinary”. The Prime Minister first detailed a set of social injustices linked to impoverishment, racism, and mental health. However, May argued in the following paragraph that the mission to build a “stronger, fairer Britain” had to go further. She then set aside those “obvious injustices” that she had just listed for a focus on the “everyday injustices that ordinary working class families feel are too often overlooked”. These injustices did not pertain to social exclusions and inequalities born from poverty, racism or disability but were rather related to income security and inter-generational social mobility. Effectively, May normalized the working class beneficiary of Brexit as a capable white family that sought to preserve its orderly independence. Critical responses to the rise of right-wing populism in the Western World have done much to draw attention to the racialization of moral economies. It has become clear that the white working class is the fundamental constituency of contemporary populist imaginaries – a constituency unfairly left behind and now deserving of redemption from the vicissitudes of globalization including competition from non-white and/or migrant labour (for example Tilley 2017; Roediger 2017; Bhambra 2017; Virdee and McGeever 2017; Emejulu 2016; Sayer 2017). -

Analysing and Exploring the Global City London: Modernity, Empire and Globalisation

LNDN URBS 3345: Analysing and Exploring the Global City London: Modernity, Empire and Globalisation CAPA LONDON PROGRAM Course Description Cities around the world are striving to be ‘global’. This course focuses on the development of one of the greatest of these global cities, London, from the nineteenth through to the twenty first century and investigates the nature and implications of its ‘globality’ for its built environment and social geography. We will examine how the city has been transformed by the forces of industrialisation, imperialism and globalisation and consider the ways in which London and its inhabitants have been shaped by their relationships with the rest of the world. Students will gain insight into London’s changing identity as a world city, with a particular emphasis on analysis of the city’s imperial, postcolonial and transatlantic connections; the ways in which past and present, local and global intertwine in the capital; and comparative study of urban change worldwide. The course is organised chronologically: themes include the Victorian metropolis; London as an imperial space; representations of the city in media, film and popular culture; multicultural London; London as a commercial centre of global capitalism; the impact of the Olympics and other urban ‘mega- events’; future scenarios of urban change. 1 Course Aims The course will mix classroom work with experiential learning, and will be centred on field studies to sites such as Brixton, Spitalfields, Southbank, and the Olympic sites in East London to give students the opportunity to experience the city’s varied urban geographies first hand and interact with these sites in an informed and analytical way. -

Georgeosborne 310812.Indd

Praise for George Osborne: The Austerity Chancellor ‘Janan Ganesh’s George Osborne: The Austerity Chancellor treads with skill and flair the awkward line between authorised and unauthorised biography. Ganesh … has an intuitive grasp of the Tory psyche … Revealing, penetrating, stylish and superbly written. Honestly, it’s a page-turner.’ – Matthew Parris ‘This timely book will be widely read by those wishing to understand one of the most powerful politicians of recent times. A lively account of the Chancellor’s career … it contains a great deal of fascinating new information.’ – Peter Oborne, Daily Telegraph ‘Ganesh’s dissection of what has driven the intellectual and political revival of the Tories is forensic and incisive.’ – Anne McElvoy, Mail on Sunday ‘Detailed and illuminating … an important biography.’ – The Guardian ‘Well researched, thoughtful and full of nuggets buried into the smoothest of prose … Ganesh treads deftly.’ – Independent on Sunday ‘This excellent biography … an insight into one of today’s most important politicians is extremely valuable.’ – Sunday Express ‘Janan Ganesh has produced a book that readers of all sorts will enjoy and dip into in the future. The author really knows his stuff.’ – Financial Times ‘Excellent biography.’ – John Rentoul ‘A pacy, well-researched book.’ – The Spectator ‘Fascinating biography.’ – Ted Jeory ‘Ganesh spills the beans as politely as possible.’ – Belfast Telegraph ‘Janan Ganesh produces a meticulously researched biography.’ – Oxford Today Prologue his is the unavoidable Budget.’ Summoned to speak at 12.34 p.m. on Tuesday 22 June 2010, the new ‘TChancellor of the Exchequer itemised the monstrosi- ties of his economic inheritance. In all of Europe only neighbour- ing, unravelling Ireland was running a deeper fiscal deficit, he told the House of Commons. -

David Starkey Published by Harper Press

Henry Virtuous Prince David Starkey Published by Harper Press Extract All text is copyright of the author This opening extract is exclusive to Lovereading. Please print off and read at your leisure. Henry 9/2/08 2:30 PM Page iv HarperPress An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London W6 8JB www.harpercollins.co.uk Visit our authors’ blog: www.fifthestate.co.uk First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2008 Copyright © Jutland Ltd 2008 Family tree © HarperCollinsPublishers, designed by HL Studios, Oxfordshire 1 David Starkey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library HB ISBN 978-0-00-724771-4 TPB ISBN 978-0-00-729263-9 Typeset in Bell MT by G&M Designs Limited, Raunds, Northamptonshire Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc FSC is a non-profit international organisation established to promote the responsible management of the world’s forests. Products carrying the FSC label are independently certified to assure consumers that they come from forests that are managed to meet the social, economic and ecological needs of present or future generations. Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Henry 9/2/08 2:30 PM Page 1 INTRODUCTION Henry and I go back a long way. -

Revolt of the Rustbelt

tom hazeldine REVOLT OF THE RUSTBELT n the space of less than a year, the established political order of Ukania has received two successive, jolting blows—a referendum in which a population voted, against the express will of the leadership of all three major parties and an overwhelming major- Iity of the country’s parliament, to leave the European Union; followed by an election in which a 20 per cent lead in opinion polls for the sitting government vanished overnight, and the most radical opposition pro- gramme since Thatcherism, presented by the most vilified leader in the history of the country’s media, came close enough to victory to generate a hung parliament—one now confronted with fraught negotiations over the terms of departure from the eu. The dismay of bourgeois opinion at the plight of the state is the best register of the effect of the two temblors. ‘Chronic instability’, lamented the Economist, ‘has taken hold of British politics’, and it ‘will be hard to suppress’. Readers had to ask themselves: ‘What can come of this chaos?’1 The answer from the Financial Times was grimly tight-lipped: ‘The stablest of democracies has become the western world’s box of surprises.’2 To understand the dynamics that have produced this situation, the starting -point has to be a closer analysis of the pattern of Brexit. Like any popular poll, the 23 June 2016 referendum can be broken down in a variety of ways. But as the dust has started to settle, some facts stand out. Nationalist dynamics produced wins for Remain in Scotland and Northern Ireland, while Wales’s 80,000 net votes for Leave amounted to only 6 per cent of Brexit’s winning margin. -

Archived BBC Public Responses to Complaints 2020 BBC News, Royal

Archived BBC public responses to complaints 2020 BBC News, Royal Family coverage, January 2020 Summary of complaint We were contacted by viewers who were unhappy with the level of coverage given to the Duke and Duchess of Sussex's announcement that they will be 'stepping back' as senior royals. Our response In our editorial judgement, the announcement that the Duke and Duchess of Sussex planned to quit their frontline roles was a major news story of great constitutional significance as well as widespread public interest. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex have a very high profile at home and abroad and their decision affects the entire Royal Family, as well as raising questions about the levels of public support they enjoy and their charitable roles too. We appreciate viewers may not agree with how this story was covered, but we also made space for other major stories, including developments in Iran and Australia, both of which we have given extensive airtime. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- BBC World Service, Sinhala, January 2020 Summary of complaint We received a number of complaints about BBC Sinhala correspondent, Azzam Ameen, with concerns over his conduct during the Sri-Lankan presidential election. Our response Editorial impartiality is the foundation of the BBC’s global reputation as a trusted news source and this is something which cannot be compromised. The BBC has taken appropriate action as a result of this serious breach of its Editorial Guidelines. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Question Time, BBC One, 16 January 2020 Summary of complaint We were contacted by viewers who were unhappy with the audience makeup of the programme.