Download Issue 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington DC Hike

HISTORIC D.C. MALL HIKE SATELLITE VIEW OF HIKE 2 Waypoints with bathroom facilities are in to start or end the hike and is highly the left (south side) far sidewalk until you ITALIC. Temporary changes or notes are recommended. The line for the tour can see a small white dome a third of the way in bold. be pretty long. If it’s too long when you and 300 feet to the south. Head to that first go by, plan to include it towards the dome. BEGINNING THE HIKE end of the day. Parking can be quite a challenge. It is OR recommended to park in a garage and GPS Start Point: take public transportation to reach The 27°36’52.54”N 82°44’6.39”W Head south of the WWII Memorial Mall. until you see a parking area and a small Challenge title building. Follow the path past the bus Union Station is a great place to find Circle Up! loading area and then head east. About parking and the building itself is a must 2300 feet to the left will be a small white see! The address is: 50 Massachusetts Challenge description domed structure. Head towards it. Avenue NE. Parking costs under $20 How many flagpoles surround the per car. For youth groups, take the Metro base of the Washington Monument? GPS to next waypoint since that can be a new and interesting _____________________________ 38°53’15.28”N 77° 2’36.50”W experience for them. The station you want is Metro Center station. -

Law and Military Operations in Kosovo: 1999-2001, Lessons Learned For

LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS IN KOSOVO: 1999-2001 LESSONS LEARNED FOR JUDGE ADVOCATES Center for Law and Military Operations (CLAMO) The Judge Advocate General’s School United States Army Charlottesville, Virginia CENTER FOR LAW AND MILITARY OPERATIONS (CLAMO) Director COL David E. Graham Deputy Director LTC Stuart W. Risch Director, Domestic Operational Law (vacant) Director, Training & Support CPT Alton L. (Larry) Gwaltney, III Marine Representative Maj Cody M. Weston, USMC Advanced Operational Law Studies Fellows MAJ Keith E. Puls MAJ Daniel G. Jordan Automation Technician Mr. Ben R. Morgan Training Centers LTC Richard M. Whitaker Battle Command Training Program LTC James W. Herring Battle Command Training Program MAJ Phillip W. Jussell Battle Command Training Program CPT Michael L. Roberts Combat Maneuver Training Center MAJ Michael P. Ryan Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Peter R. Hayden Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Mark D. Matthews Joint Readiness Training Center SFC Michael A. Pascua Joint Readiness Training Center CPT Jonathan Howard National Training Center CPT Charles J. Kovats National Training Center Contact the Center The Center’s mission is to examine legal issues that arise during all phases of military operations and to devise training and resource strategies for addressing those issues. It seeks to fulfill this mission in five ways. First, it is the central repository within The Judge Advocate General's Corps for all-source data, information, memoranda, after-action materials and lessons learned pertaining to legal support to operations, foreign and domestic. Second, it supports judge advocates by analyzing all data and information, developing lessons learned across all military legal disciplines, and by disseminating these lessons learned and other operational information to the Army, Marine Corps, and Joint communities through publications, instruction, training, and databases accessible to operational forces, world-wide. -

The BG News April 2, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-2-1999 The BG News April 2, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 2, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6476. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6476 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. .The BG News mostly cloudy New program to assist disabled students Office of Disability Services offers computer program that writes what people say However, he said, "They work together," Cunningham transcripts of students' and ities, so they have an equal By IRENE SHARON (computer programs] are far less said. teachers' responses. This will chance of being successful. high: 69 SCOTT than perfect." Additionally, the Office of help deaf students to participate "We try to minimize the nega- The BG News Also, in the fall they will have Disability Services hopes to start in class actively, he said. tives and focus on similarities low: 50 The Office of Disability Ser- handbooks available for teachers an organization for disabled stu- Several disabled students rather than differences," he said. vices for Students is offering and faculty members, so they dents. expressed contentment over the When Petrisko, who has pro- additional services for the dis- can better accommodate dis- "We are willing to provide the services that the office of disabil- found to severe hearing loss, was abled community at the Univer- abled students. -

Vietnam War Literature and the Vietnam

Searching for Closure: Vietnam War Literature and the Veterans Memorial by Charles J. Gaspar That many soldiers returned home from the battlefields of Vietnam only to find themselves mired in another battle in their own country is well recognized now. A vignette which opens the Preface to Frederick Downs' compelling memoir, The Killing Zone, makes this point dramatically: In the fall of 1968, as I stopped at a traffic light on my walk to class across the campus of the University of 3enver, a man stepped up to me and said "Hi." Without waiting for my reply to his greeting, he pointed to the hook sticking out of my left sleeve. "Get that in Vietnam?" I said, "Yeah, up near Tam Ky, in I Corps." "Serves you right." As the man walked away, I stood rooted, too confused with hurt, shame, and anger to react. (n.pag. [vii]) This theme - that there was no easy closure for the trauma of the war experience for the individual soldier - recurs throughout many Vietnam War narratives. "Senator," a wounded veteran in James Webb's Fields of Fire, knows this truth and rebukes his father's cajolery with the assertion that "It'll never be over, Dad. Most of it hasn't even started yet" (392). Similarly, Tim O'Brien's hero in his first novel, Northern Lights, tells his brother only half jokingly, "Glad I didn't wear my uniform. Look plain silly coming home in a uniform and no parade" (24). Indeed, powerful recent narratives such as Larry Heinemann's Paco's Story and Philip Caputo's Indian Country have shifted the focus from the soldier in combat to the soldier as he attempts to reconnect with the mainstream of American society. -

Network of Concerned Historians NCH Annual Report 2011 Http

Network of Concerned Historians NCH Annual Report 2011 http://www.concernedhistorians.org INTRODUCTION The seventeenth Annual Report of the Network of Concerned Historians (NCH) contains news about the domain where history and human rights intersect, especially about the censorship of history and the persecution of historians, archivists, and archaeologists around the globe, as reported by various human rights organizations and other sources. It covers events and developments of 2010 and 2011. The fact that NCH presents this news does not imply that it shares the views and beliefs of the historians and others mentioned in it. The complete set of Annual Reports (1995–2011) was compiled by Antoon De Baets. Please send any comments to: <[email protected]>. Please cite as: Network of Concerned Historians, Annual Report 2011 (http://www.concernedhistorians.org). Network of Concerned Historians, Annual Report 2011 (June 2011) 2 ____________________________________________________________ AFGHANISTAN Last Annual Report entry: 2010. In early 2010, the National Stability and Reconciliation bill was officially promulgated, granting immunity from criminal prosecution to people who committed serious human rights violations and war crimes over the past thirty years. In March 2007, a coalition of powerful warlords in parliament pushed through the amnesty law to prevent prosecution of individuals responsible for large-scale human rights abuses in the preceding decades. It was not publicized and promulgated until early 2010. It was revived in 2010 to facilitate amnesties for reconciliation and reintegration of the Taliban and the islamist political party Hezb-i Islami Gulbuddin. In the absence of a practical justice system to address the lack of accountability by the warring parties, the government was urged to ask the International Criminal Court to investigate allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by all parties to the conflict. -

National Mall & Memorial Parks

COMPLIMENTARY $2.95 2017/2018 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS NATIONAL MALL & MEMORIAL PARKS ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS This summer, Yamaha launches a new Star motorcycle designed to help you journey further…than you ever thought possible. To see the road ahead, visit YamahaMotorsports.com/Journey-Further Some motorcycles shown with custom parts, accessories, paint and bodywork. Dress properly for your ride with a helmet, eye protection, long sleeves, long pants, gloves and boots. Yamaha and the Motorcycle Safety Foundation encourage you to ride safely and respect the environment. For further information regarding the MSF course, please call 1-800-446-9227. Do not drink and ride. It is illegal and dangerous. ©2017 Yamaha Motor Corporation, U.S.A. All rights reserved. BLEED AREA TRIM SIZE WELCOME LIVE AREA Welcome to our nation’s capital, Wash- return trips for you and your family. Save it ington, District of Columbia! as a memento or pass it along to friends. Zion National Park Washington, D.C., is rich in culture and The National Park Service, along with is the result of erosion, history and, with so many sites to see, Eastern National, the Trust for the National sedimentary uplift, and there are countless ways to experience Mall and Guest Services, work together this special place. As with all American to provide the best experience possible Stephanie Shinmachi. Park Network editions, this guide to the for visitors to the National Mall & Me- 8 ⅞ National Mall & Memorial Parks provides morial Parks. information to make your visit more fun, memorable, safe and educational. -

Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2001 "Soldiers of the Cross": Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith Kent Toby Dollar University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dollar, Kent Toby, ""Soldiers of the Cross": Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2001. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3237 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kent Toby Dollar entitled ""Soldiers of the Cross": Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. Stephen V. Ash, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) c.t To the Graduate Council: I am subinitting herewith a dissertation written by Kent TobyDollar entitled '"Soldiers of the Cross': Confederate Soldier-Christians and the Impact of War on Their Faith." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy,f with a major in History. -

The Last Firebase Archive Created by Lydia Fish

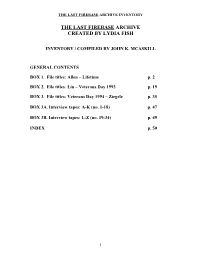

THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE CREATED BY LYDIA FISH INVENTORY / COMPILED BY JOHN K. MCASKILL GENERAL CONTENTS BOX 1. File titles: Allen – Lifetime p. 2 BOX 2. File titles: Lin – Veterans Day 1993 p. 19 BOX 3. File titles: Veterans Day 1994 – Ziegele p. 35 BOX 3A. Interview tapes: A-K (no. 1-18) p. 47 BOX 3B. Interview tapes: L-Z (no. 19-34) p. 49 INDEX p. 50 1 THE LAST FIREBASE ARCHIVE INVENTORY BOX 1. Folder titles in bold. Abercrombie, Sharon. “Vietnam ritual” Creation spirituality 8/4 (July/Aug. 1992), p. 18-21. (3 copies – 1 complete issue, 2 photocopies). “An account of a memorable occasion of remembering and healing with Robert Bly, Matthew Fox and Michael Mead”—Contents page. Abrams, Arnold. “Feeling the pain : hands reach out to the vets’ names and offer remembrances” Newsday (Nov. 9, 1984), part II, p. 2-3. (photocopy) Acai, Steve. (Raleigh, NC and North Carolina Vietnam Veterans Memorial Committee) (see also Interview tapes Box 3A Tape 1) Correspondence with LF (ALS and TLS), photos, copies of articles concerning the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the visit of the Moving Wall to North Carolina and the development of the NC VVM. Also includes some family news (Lydia Fish’s mother was resident in NC). (ca. 50 items, 1986-1991) Allen, Christine Hope. “Public celebrations and private grieving : the public healing process after death” [paper read at the American Studies Assn. meeting Nov. 4, 1983] (17 leaves, photocopy) Allen, Henry (see folder titled: Vietnam Veterans Memorial articles) Allen, Jane Addams (see folder titled: The statue) Allen, Leslie. -

The Ephemera of Dissident Memory: Remembering Military Violence in 21St-Century American War Culture

THE EPHEMERA OF DISSIDENT MEMORY: REMEMBERING MILITARY VIOLENCE IN 21 ST -CENTURY AMERICAN WAR CULTURE Bryan Thomas Walsh Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Culture Indiana University February, 2017 i Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________________________ John Lucaites, PhD. _______________________________________________ Robert Ivie, PhD. _______________________________________________ Robert Terrill, PhD. _______________________________________________ Edward Linenthal, PhD. Date of Defense: January 25 th , 2017 ii Acknowledgements If I’m the author of this manuscript, then my colleagues are its grammar. I am forever grateful to the following professors for serving a vital role in my intellectual, emotional, and political development: Susan Owen, Anne Demo, Jim Jasinski, Kendall Phillips, Bradford Vivian, Derek Buescher, Diane Grimes, Linda Alcoff, Roger Hallas, and Dexter Gordon. I first pursued a career in higher education, because I believed that every student should go through an education similar to my own – one that transforms the way we see the world and our place in it. For everything, thank you. I could not have completed this manuscript were it not for my fellow graduate colleagues. Theirs was a friendship of comradery, and they kept me -

Why Lenin Succeeds

• ~ . I ~ WHY LENIN SUCCEEDS ( j ) Henri Guilbeaux, writing in "Moscow," states "H istory has known political gen iuses, great reform ists, audacious and glorious conquerors, but L enin alone, up to this day, has subordi nated his personality, his power, to a do c trine which he pro fessed at a period when he, humble, dis dained and calum niated had propagated - Marxism , }. , ' L enin is the very personification of the theory and practice of M arxism_" "Marx's wonderful critico analytical mind. "---Lenin. ,LENIN .. ':~ Works of Marx ~nd Erzgels Other Classical Works Capital- I. Processes of ~a pi~ali l' t Pmdu,~: ,,~-' .• , ',..> J;>o~iti ve <?utcome of Ph~l osoPltY~Dietig~n.. _:t: $1.50 tion ____ , __ __ __:.. ____ ___ < ___,<'''---- -- ----..:~- ~, $2}50 i,Phllosollh;lcal Essays-Dletzgfn ___ , __ _____ .. , ___ ___ ,_"-""_ _'. 1.50 Capital-II. The ~roce ss ' nf , tlt~y.rrif!iI of ' jl';~' M~h~r~~id of Dietzgen: " T ~~,~~ ~S O~l' _P~~ ,~.o s oC~, Ca?~ta l-lIL c.a~~i~ Ji~~ p~~~~ -~t-f6~--~~ - ~'Wh~ i ~ ; : ~; ':::;\(;a~i~:!i;~d~;.ou:~:,~~~C~~d;i~-~- :-,--::- : -- ',------: ." ' :~- 2:00 Cntlque of Pobtlcal Economy ----( '---------------;~--.--- ' . 1.2;> , ;~,:Eco noIl1ic · Ca,use-s of W rir-":PrOf. · Loria ______________ . 1.25 Eighteenth Brumaire -------- ;-- ----.:--. ---- .----.-- ------ ,.:--- .75 ,',';;" A Marxi,s.t -on· economic imperialism. Poverty of Philosophy ____ _________ . __ .: __ ____________ ___ :__ , __ ... 1.25 , ,>Ristory of 'the ' Supreme · ,Court-Gustavus ,\ Revolution and Counter-Revolution ____ .:___ .. ___ .: .. _. .75 ":,';: Myers ______ _____ L~~,,: : ___ :____ __ . __ ______ .. _______ ___________ . -

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Citizenship

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Citizenship “What We Stand For” C8C: Symbols of American Pride Updated 30 JAN 2021 Symbols of American Pride • C1. The Washington Monument • C2. The Lincoln and Jefferson Memorials • C3. The US Capitol • C4. The White House • C5. The Statue of Liberty • C6. The Liberty Bell • C7. Mount Rushmore • C8. US and California Seals • C9. Patriotic Holidays • C10. The Medal of Honor • C11. Arlington Cemetery and Tomb of the Unknown Soldier • C12. The World War II Memorial • C13. The US Marine Corps Memorial • C14. The Korean War Memorial • C15. The Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial • C16. Significant American Accomplishments The National Mall THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT OBJECTIVES DESIRED OUTCOME (Leadership) At the conclusion of this training, Cadets will be familiar with the major symbols of American pride that represent American people, history, and national identity. Plan of Action: 1. Describe the Washington Monument, its key features, and why it is a symbol of American pride. Essential Question: What is the Washington Monument and why is it a symbol of American pride? Washington Monument • Stone obelisk • Opened in 1888 • Western end of the National Mall • Commemorates George Washington – First President – Father of our Country – Commander of Continental Army National Mall Washington DC Details • 555 feet high – tallest building in Washington DC; one of tallest in the world • 50 state flags circle the monument • Stairs (now unused) & elevator to Observation Room at the top – windows on each side • 4 walls are 55 feet long, 15 feet thick at base • Top is called a pyramidion – small capped pyramid • Two shades of stone, changing at about 100 feet up – Break in construction; original quarry wasn’t available Check on Learning 1. -

World War I in the Novels of John Dos Passos

RICE UNIVERSITY World War I in the Novels of John Dos Passos Alice Jacob Allen A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts Thesis Director's signature: Houston, Texas May, 1966 (JLSIUIAJOIOI&&&-' IWJJLY ABSTRACT John Dos Passos was one of a "war generation" of young novelists for whom World War I was a source of excitement and then disillusionment. The works of Heming¬ way, Cummings, and others illustrate this, hut for Dos Passos the war became a preoccupation which lasted through most of his writing career. Like many other young novelists, Dos Passos sax^ the war as an ambulance driver. This gave him direct personal experience with war, which he later utilized in his novels. This study examines three xvorks, First Encounter, Three Soldiers, and U.S.A., to show how Dos Passos reworked the materials of (his personal experience each time for a different effect and to a different purpose. First Encounter is a generally direct rendering of Dos Passos’ life as an ambulance driver. The central character, Martin Howe, is a sensitive and thoughtful observer much like the young Dos Passos. He embarks for France and the ambulance corps in search of adventure. During his period at the front he undergoes an initiation experience of uncertain nature, which gives him a more mature view of war. The novel is an immature and unsuccessful work, important only for the introduction of motifs which appear in later Dos Passos novels. In Three Soldiers Dos Passos imposes some sort of form on his material.