The RUNX Transcriptional Coregulator, Cbfβ, Suppresses Migration of ER+ Breast Cancer Cells by Repressing Erα-Mediated Express

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Functions of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor in the Hippocampus By

Functions of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor in the Hippocampus by Aaron M. Rozeboom A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Cellular and Molecular Biology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Audrey F. Seasholtz, Chair Professor Elizabeth A. Young Professor Ronald Jay Koenig Associate Professor Gary D. Hammer Assistant Professor Jorge A. Iniguez-Lluhi Acknowledgements There are more people than I can possibly name here that I need to thank who have helped me throughout the process of writing this thesis. The first and foremost person on this list is my mentor, Audrey Seasholtz. Between working in her laboratory as a research assistant and continuing my training as a graduate student, I spent 9 years in Audrey’s laboratory and it would be no exaggeration to say that almost everything I have learned regarding scientific research has come from her. Audrey’s boundless enthusiasm, great patience, and eager desire to teach students has made my time in her laboratory a richly rewarding experience. I cannot speak of Audrey’s laboratory without also including all the past and present members, many of whom were/are not just lab-mates but also good friends. I also need to thank all the members of my committee, an amazing group of people whose scientific prowess combined with their open-mindedness allowed me to explore a wide variety of interests while maintaining intense scientific rigor. Outside of Audrey’s laboratory, there have been many people in Ann Arbor without whom I would most assuredly have gone crazy. -

Variant Transcript in a Patient with Therapy-Related Acute Myeloid Leukemia by Routine Leukemia Translocation Panel Screen: Implications for Diagnosis and Therapy

Downloaded from molecularcasestudies.cshlp.org on October 7, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press COLD SPRING HARBOR Molecular Case Studies | RESEARCH ARTICLE Incidental identification of inv(16)(p13.1q22)/CBFB–MYH11 variant transcript in a patient with therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia by routine leukemia translocation panel screen: implications for diagnosis and therapy Andrés E. Quesada,1 Rajyalakshmi Luthra,1 Elias Jabbour,2 Keyur P. Patel,1 Joseph D. Khoury,1 Zhenya Tang,1 Hector Alvarez,1 Saradhi Mallampati,1 Guillermo Garcia-Manero,2 Guillermo Montalban-Bravo,2 L. Jeffrey Medeiros,1 and Rashmi Kanagal-Shamanna1 1Department of Hematopathology, 2Department of Leukemia, The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas 77030, USA Abstract A 52-yr-old woman presented with therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia. A bone marrow biopsy showed 21% blasts with a myeloid phenotype and no other notable features such as abnormal eosinophils. Routine nanofluidics-based reverse transcriptase po- lymerase chain reaction (PCR) leukemia translocation panel designed to screen for recurrent genetic abnormalities in acute leukemia detected an inversion 16 transcript variant E. This prompted rereview of karyotype and fluorescence in situ hybridization studies, which con- firmed inv(16), leading to appropriate prognostication and modification of treatment. This Corresponding author: case underscores the utility of a powerful molecular screening method for the routine detec- [email protected] tion of recurrent genetic abnormalities of acute myeloid leukemia. It was especially useful in this case because of the lack of characteristic morphologic findings seen in inversion 16 and the difficulty in its detection by conventional karyotype analysis. -

Core Binding Factor Β Is Required for Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Activation

Cutting Edge: Core Binding Factor β Is Required for Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Activation This information is current as Xiaofei Shen, Mingwei Liang, Xiangyu Chen, Muhammad of September 24, 2021. Asghar Pasha, Shanti S. D'Souza, Kelsi Hidde, Jennifer Howard, Dil Afroz Sultana, Ivan Ting Hin Fung, Longyun Ye, Jiexue Pan, Gang Liu, James R. Drake, Lisa A. Drake, Jinfang Zhu, Avinash Bhandoola and Qi Yang J Immunol 2019; 202:1669-1673; Prepublished online 6 Downloaded from February 2019; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800852 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/202/6/1669 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2019/02/05/jimmunol.180085 Material 2.DCSupplemental References This article cites 20 articles, 10 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/202/6/1669.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. by guest on September 24, 2021 • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2019 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. -

And EZH2-Regulated Gene, Has Differential Roles in AR-Dependent and -Independent Prostate Cancer

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 6, No.4 RUNX1, an androgen- and EZH2-regulated gene, has differential roles in AR-dependent and -independent prostate cancer Ken-ichi Takayama1,2, Takashi Suzuki3, Shuichi Tsutsumi4, Tetsuya Fujimura5, Tomohiko Urano1,2, Satoru Takahashi6, Yukio Homma5, Hiroyuki Aburatani4 and Satoshi Inoue1,2,7 1 Department of Anti-Aging Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan 2 Department of Geriatric Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan 3 Department of Pathology, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, Sendai, Miyagi, Japan 4 Genome Science Division, Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology (RCAST), The University of Tokyo, Meguro-ku, Tokyo, Japan 5 Department of Urology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan 6 Department of Urology, Nihon University School of Medicine, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan 7 Division of Gene Regulation and Signal Transduction, Research Center for Genomic Medicine, Saitama Medical University, Hidaka, Saitama, Japan Correspondence to: Satoshi Inoue, email: [email protected] Keywords: RUNX1, androgen receptor, EZH2, prostate cancer Received: October 02, 2014 Accepted: December 09, 2014 Published: December 10, 2014 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Androgen receptor (AR) signaling is essential for the development of prostate cancer. Here, we report that runt-related transcription factor (RUNX1) could be a key molecule for the androgen-dependence of prostate cancer. We found RUNX1 is a target of AR and regulated positively by androgen. -

Mechanism of Leukemogenesis by the Inv(16) Chimeric Gene CBFB/PEBP2B-MHY11

Oncogene (2004) 23, 4297–4307 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/04 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc Mechanism of leukemogenesis by the inv(16) chimeric gene CBFB/PEBP2B-MHY11 Katsuya Shigesada*,1, Bart van de Sluis2 and P Paul Liu*,2 1Department of Cell Biology, Institute for Virus Research, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8507, Japan; 2Oncogenesis and Development Section, National Human Genome Research Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA Inv(16)(p13q22) is associated with acute myeloid leukemia subsequent to which a certain mechanism(s) should act subtype M4Eo that is characterized by the presence of to bring Runx1 into a functionally incompetent state in myelomonocytic blasts and atypical eosinophils. This the end (repression).If one of these steps were lacking or chromosomal rearrangement results in the fusion of CBFB impaired, CBFb-SMMHC would fail to elicit any and MYH11 genes. CBFb normally interacts with RUNX1 substantial dominant-negative effect regardless of how to form a transcriptionally active nuclear complex. well the other step might work. The MYH11 gene encodes the smooth muscle myosin Until recently, however, most functional studies of heavy chain. The CBFb-SMMHC fusion protein is CBFb-SMMHC have centered around the mechanism capable of binding to RUNX1 and form dimers and of repression, paying relatively little attention to the first multimers through its myosin tail. Previous results from heterodimerization step.Nevertheless, evidence sugges- transgenic mouse models show that Cbfb-MYH11 is able tive of its enhanced ability for heterodimerization to inhibit dominantly Runx1 function in hematopoiesis, (hyper-heterodimerization) has come from our previous and is a key player in the pathogenesis of leukemia. -

Mutational Landscape and Clinical Outcome of Patients with De Novo Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Rearrangements Involving 11Q23/KMT2A

Mutational landscape and clinical outcome of patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia and rearrangements involving 11q23/KMT2A Marius Billa,1,2, Krzysztof Mrózeka,1,2, Jessica Kohlschmidta,b, Ann-Kathrin Eisfelda,c, Christopher J. Walkera, Deedra Nicoleta,b, Dimitrios Papaioannoua, James S. Blachlya,c, Shelley Orwicka,c, Andrew J. Carrolld, Jonathan E. Kolitze, Bayard L. Powellf, Richard M. Stoneg, Albert de la Chapelleh,i,2, John C. Byrda,c, and Clara D. Bloomfielda,c aThe Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH 43210; bAlliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Statistics and Data Center, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH 43210; cDivision of Hematology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH 43210; dDepartment of Genetics, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294; eNorthwell Health Cancer Institute, Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell, Lake Success, NY 11042; fDepartment of Internal Medicine, Section on Hematology & Oncology, Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center, Winston-Salem, NC 27157; gDepartment of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber/Partners Cancer Care, Boston, MA 02215; hHuman Cancer Genetics Program, Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210; and iDepartment of Cancer Biology and Genetics, Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 Contributed by Albert de la Chapelle, August 28, 2020 (sent for review July 17, 2020; reviewed by Anne Hagemeijer and Stefan Klaus Bohlander) Balanced rearrangements involving the KMT2A gene, located at patterns that include high expression of HOXA genes and thereby 11q23, are among the most frequent chromosome aberrations in contribute to leukemogenesis (14–16). -

Figure S17 Figure S16

immune responseregulatingcellsurfacereceptorsignalingpathway ventricular cardiacmuscletissuedevelopment t cellactivationinvolvedinimmuneresponse intrinsic apoptoticsignalingpathway single organismalcelladhesion cholesterol biosyntheticprocess myeloid leukocytedifferentiation determination ofadultlifespan response tointerferongamma muscle organmorphogenesis endothelial celldifferentiation brown fatcelldifferentiation mitochondrion organization myoblast differentiation response toprotozoan amino acidtransport leukocyte migration cytokine production t celldifferentiation protein secretion response tovirus angiogenesis Scrt1 Tcf25 Dpf1 Sap30 Ing2 Zfp654 Sp9 Zfp263 Mxi1 Hes6 Zfp395 Rlf Ppp1r13l Snapc1 C030039L03Rik Hif1a Arrb1 Glis3 Rcor2 Hif3a Fbxo21 Dnajc21 Rest Sirt6 Foxj1 Kdm5b Ankzf1 Sos2 Plscr1 Jdp2 Rbbp8 Etv4 Msh5 Mafg Tsc22d3 Nupr1 Ddit3 Cebpg Zfp790 Atf5 Cebpb Atf3 Trim21 Irf9 Irf2 Tbx21 Stat2 Stat1 Zbp1 Irf1 aGOslimPos Ikzf3 Oasl1 Irf7 Trim30a Dhx58 Txk Rorc Rora Nr1d2 Setdb2 Vdr Vax2 Nr1d1 Foxs1 Eno1 Thap3 Nfkbil1 Edf1 Srebf1 Lbr Tead1 Zfp608 Pcx Ift57 Ssbp4 Stat3 Mxd1 Pml Ssh2 Chd7 Maf Cic Bcl3 Prkdc Mbd5 Ppfibp2 Foxp2 Tal2 Mlf1 Bcl6b Zfp827 Ikzf2 Phtf2 Bmyc Plagl2 Nfkb2 Nfkb1 Tox Nrip1 Utf1 Klf3 Plagl1 Nfkbib Spib Nfkbie Akna Rbpj Ncoa3 Id1 Tnp2 Gata3 Gata1 Pparg Id2 Epas1 Zfp280b Commons Pathway Erg GO MSigDB KEGG Hhex WikiPathways SetGene Databases Batf Aff3 Zfp266 gene modules other (hypergeometric TF, from Figure Trim24 Zbtb5 Foxo3 Aebp2 XPodNet -protein-proteininteractionsinthepodocyteexpandedbySTRING Ppp1r10 Dffb Trp53 Enrichment -

Temporal Proteomic Analysis of HIV Infection Reveals Remodelling of The

1 1 Temporal proteomic analysis of HIV infection reveals 2 remodelling of the host phosphoproteome 3 by lentiviral Vif variants 4 5 Edward JD Greenwood 1,2,*, Nicholas J Matheson1,2,*, Kim Wals1, Dick JH van den Boomen1, 6 Robin Antrobus1, James C Williamson1, Paul J Lehner1,* 7 1. Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, Department of Medicine, University of 8 Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK. 9 2. These authors contributed equally to this work. 10 *Correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 11 12 Abstract 13 Viruses manipulate host factors to enhance their replication and evade cellular restriction. 14 We used multiplex tandem mass tag (TMT)-based whole cell proteomics to perform a 15 comprehensive time course analysis of >6,500 viral and cellular proteins during HIV 16 infection. To enable specific functional predictions, we categorized cellular proteins regulated 17 by HIV according to their patterns of temporal expression. We focussed on proteins depleted 18 with similar kinetics to APOBEC3C, and found the viral accessory protein Vif to be 19 necessary and sufficient for CUL5-dependent proteasomal degradation of all members of the 20 B56 family of regulatory subunits of the key cellular phosphatase PP2A (PPP2R5A-E). 21 Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of HIV-infected cells confirmed Vif-dependent 22 hyperphosphorylation of >200 cellular proteins, particularly substrates of the aurora kinases. 23 The ability of Vif to target PPP2R5 subunits is found in primate and non-primate lentiviral 2 24 lineages, and remodeling of the cellular phosphoproteome is therefore a second ancient and 25 conserved Vif function. -

Inhibition of HIF1` Signaling: a Grand Slam for MDS Therapy?

VIEWS IN THE SPOTLIGHT Inhibition of HIF1` Signaling: A Grand Slam for MDS Therapy? Jiahao Chen and Ulrich Steidl Summary: The recent focus on genomics in myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) has led to important insights and revealed a daunting genetic heterogeneity, which is presenting great challenges for clinical treatment and preci- sion oncology approaches in MDS. Hayashi and colleagues show that multiple mutations frequently found in MDS activate HIF1α signaling, which they also found to be suffi cient to induce overt MDS in mice. Furthermore, both genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of HIF1α suppressed MDS development with only mild effects on normal hematopoiesis, implicating HIF1α signaling as a promising therapeutic target to tackle the heterogeneity of MDS. Cancer Discov; 8(11); 1355–7. ©2018 AACR . See related article by Hayashi et al., p. 1438 (5). Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a heterogeneous In this issue, Hayashi and colleagues found that target group of hematologic disorders characterized by ineffi cient genes activated by HIF1α signaling were highly expressed in hematopoiesis that manifests as bone marrow (BM) dysplasia a published cohort of 183 patients with MDS compared with and peripheral blood cytopenias, and increased risk of leuke- healthy controls ( 5 ). IHC confi rmed an increased frequency mic transformation ( 1 ). The median survival of patients with of HIF1α-expressing cells in MDS samples at different stages MDS is 4.5 years, with a signifi cantly worse survival of< 1 year (low-, intermediate-, and high-risk) -

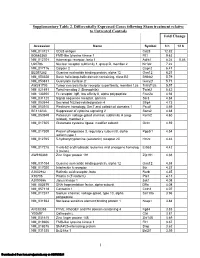

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 2. Differentially Expressed Genes following Sham treatment relative to Untreated Controls Fold Change Accession Name Symbol 3 h 12 h NM_013121 CD28 antigen Cd28 12.82 BG665360 FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 Flt1 9.63 NM_012701 Adrenergic receptor, beta 1 Adrb1 8.24 0.46 U20796 Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 Nr1d2 7.22 NM_017116 Calpain 2 Capn2 6.41 BE097282 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 6.21 NM_053328 Basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B2 Bhlhb2 5.79 NM_053831 Guanylate cyclase 2f Gucy2f 5.71 AW251703 Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a Tnfrsf12a 5.57 NM_021691 Twist homolog 2 (Drosophila) Twist2 5.42 NM_133550 Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide Fcer2a 4.93 NM_031120 Signal sequence receptor, gamma Ssr3 4.84 NM_053544 Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 Sfrp4 4.73 NM_053910 Pleckstrin homology, Sec7 and coiled/coil domains 1 Pscd1 4.69 BE113233 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 Socs2 4.68 NM_053949 Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag- Kcnh2 4.60 related), member 2 NM_017305 Glutamate cysteine ligase, modifier subunit Gclm 4.59 NM_017309 Protein phospatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha Ppp3r1 4.54 isoform,type 1 NM_012765 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2C Htr2c 4.46 NM_017218 V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog Erbb3 4.42 3 (avian) AW918369 Zinc finger protein 191 Zfp191 4.38 NM_031034 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 4.38 NM_017020 Interleukin 6 receptor Il6r 4.37 AJ002942 -

RUNX1 Together with a Compendium of Hematopoietic Regulators, Chromatin Modifiers and Basal Transcr

Leukemia (2014) 28, 770–778 OPEN & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0887-6924/14 www.nature.com/leu ORIGINAL ARTICLE CBFB–MYH11/RUNX1 together with a compendium of hematopoietic regulators, chromatin modifiers and basal transcription factors occupies self-renewal genes in inv(16) acute myeloid leukemia A Mandoli1, AA Singh1, PWTC Jansen2, ATJ Wierenga3,4, H Riahi1, G Franci5, K Prange1, S Saeed1, E Vellenga3, M Vermeulen2, HG Stunnenberg1 and JHA Martens1 Different mechanisms for CBFb–MYH11 function in acute myeloid leukemia with inv(16) have been proposed such as tethering of RUNX1 outside the nucleus, interference with transcription factor complex assembly and recruitment of histone deacetylases, all resulting in transcriptional repression of RUNX1 target genes. Here, through genome-wide CBFb–MYH11-binding site analysis and quantitative interaction proteomics, we found that CBFb–MYH11 localizes to RUNX1 occupied promoters, where it interacts with TAL1, FLI1 and TBP-associated factors (TAFs) in the context of the hematopoietic transcription factors ERG, GATA2 and PU.1/SPI1 and the coregulators EP300 and HDAC1. Transcriptional analysis revealed that upon fusion protein knockdown, a small subset of the CBFb–MYH11 target genes show increased expression, confirming a role in transcriptional repression. However, the majority of CBFb–MYH11 target genes, including genes implicated in hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal such as ID1, LMO1 and JAG1, are actively transcribed and repressed upon fusion protein knockdown. Together these results suggest an essential role for CBFb–MYH11 in regulating the expression of genes involved in maintaining a stem cell phenotype. Leukemia (2014) 28, 770–778; doi:10.1038/leu.2013.257 Keywords: CBFb–MYH11; RUNX1; histone acetylation; acute myeloid leukemia; inv(16) INTRODUCTION Heterozygous Cbfb-Myh11 knock-in mice are embryonic lethal, Core-binding transcription factors (CBFs) have roles in stem cell with definitive hematopoiesis blocked at the stem-cell level. -

A KMT2A-AFF1 Gene Regulatory Network Highlights the Role of Core Transcription Factors and Reveals the Regulatory Logic of Key Downstream Target Genes

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 7, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research A KMT2A-AFF1 gene regulatory network highlights the role of core transcription factors and reveals the regulatory logic of key downstream target genes Joe R. Harman,1,7 Ross Thorne,1,7 Max Jamilly,2 Marta Tapia,1,8 Nicholas T. Crump,1 Siobhan Rice,1,3 Ryan Beveridge,1,4 Edward Morrissey,5 Marella F.T.R. de Bruijn,1 Irene Roberts,3,6 Anindita Roy,3,6 Tudor A. Fulga,2,9 and Thomas A. Milne1,6 1MRC Molecular Haematology Unit, MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; 2MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Radcliffe Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; 3MRC Molecular Haematology Unit, MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, Department of Paediatrics, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; 4Virus Screening Facility, MRC Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; 5Center for Computational Biology, Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Oxford, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford OX3 9DS, United Kingdom; 6NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Haematology Theme, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DS, United Kingdom Regulatory interactions mediated by transcription factors (TFs) make up complex networks that control cellular behavior. Fully understanding these gene regulatory networks (GRNs) offers greater insight into the consequences of disease-causing perturbations than can be achieved by studying single TF binding events in isolation. Chromosomal translocations of the lysine methyltransferase 2A (KMT2A) gene produce KMT2A fusion proteins such as KMT2A-AFF1 (previously MLL-AF4), caus- ing poor prognosis acute lymphoblastic leukemias (ALLs) that sometimes relapse as acute myeloid leukemias (AMLs).