SS101.Mp3 David Yellin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TN-CTSI Research Study Recruitment Resources

RESEARCH STUDY RECRUITMENT RESOURCES UTHSC Electronic Data Warehouse 901.287.5834 | [email protected] | cbmi.lab.uthsc.edu/redw The Center for Biomedical Informatics (CBMI) at UTHSC has developed Research Enterprise Data Warehouse (rEDW) – a standardized aggregated healthcare data warehouse from Methodist Le Bonheur Health System. Our mission is to develop a single, comprehensive and integrated warehouse of all pediatric and adult clinical data sources on the campus to facilitate healthcare research, healthcare operations and medical education. The rEDW is an informatics tool available to researchers at UTHSC and Methodist Health System to assist with generating strong, data-driven hypotheses. Via controlled searches of the rEDW, UTHSC researchers will have the ability to run cohort queries, perform aggregated analyses and develop evidenced preparatory to research study plans. ResearchMatch.org The ResearchMatch website is a web-based tool that was established as a unique collaborative effort with participating sites in the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium and is hosted by Vanderbilt University. UTHSC is a participating ResearchMatch (RM) is a registry allowing anyone residing in the United States to self-register as a potential research participant. Researchers can register their studies on ResearchMatch after IRB approval is granted. The ResearchMatch system employs a ‘matching’ model – Volunteers self-register and Researchers search for Volunteers for their studies. Social Media Facebook — Form and info to advertise -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

History Happenings

History Happenings The University of Memphis Fall 2005 History Happenings An annual newsletter published by The University of Memphis Department of History Janann M. Sherman Chair Table of Contents James Blythe Graduate Coordinator Greetings from the Chair page 3 Beverly Bond Retirement Tribute page 4 Walter R. (Bob) Brown Where are They Now? page 5 Director, Undergraduate Studies History Day Update page 6 Margaret M. Caffrey Staff Happenings page 7 James Chumney Postcard from Egypt page 8 Charles W. Crawford Awards and Kudos page 9 Director, Oral History Research Offi ce Faculty Happenings page 10 Maurice Crouse A Tribute to Teachers page 16 Douglas W. Cupples Teachers in the News page 17 Guiomar Duenas-Vargas Graduate Happenings page 18 James E. Fickle GAAAH Conference page 22 Robert Frankle Dissertations and A.B.D. Progress page 23 Aram Goudsouzian Undergraduate Happenings page 24 Robert Gudmestad Phi Alpha Theta Update page 25 Joseph Hawes Back to School Night page 27 Jonathan Judaken Abraham D. Kriegel Dennis Laumann Kevin W. Martin Kell Mitchell, Jr. D'Ann Penner C. Edward Skeen Arwin Smallwood Stephen Stein Lung-Kee Sun Daniel Unowsky Department of History Staff On the Cover: Karen Bradley Senior Administrative Secretary “Parallel Lives: Black and White Women in Amanda Sanders American History” Offi ce Assistant Ronnie Biggs A quilt created by the graduate students of Secretary, History/OHRO HIST 7980/8980, Spring 2005 Greetings from the Chair... e have had an extraordinary year in the History Department. PersonnelW changes, curriculum revisions, and new projects keep us excited and invigorated. Drs. Beverly Bond, Aram Goudsouzian, and Arwin Smallwood exam- ined and extensively revised our African American history curriculum, and the department added a Ph.D. -

WDIA from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

WDIA From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia WDIA City of Memphis, Tennessee license Broadcast Memphis, Tennessee area Branding AM 1070 WDIA Slogan The Heart and Soul of Memphis Frequency 1070 kHz KJMS 101.1 FM HD-2 (simulcast) First air date June 7, 1947 Format Urban Oldies/Classic Soul Power 50,000 watts daytime 5,000 watts nighttime Class B Facility ID 69569 Callsign DIAne, name of original owner's daughter meaning We Did It Again (when owners also launched similar station in Jackson, Mississippi, after World War II) Owner iHeartMedia, Inc. Sister KJMS, WEGR, WHAL-FM, WHRK,WREC stations Under LMA: KWAM Webcast Listen Live Website http://www.mywdia.com/main.html WDIA is a radio station based in Memphis, Tennessee. Active since 1947, it soon became the first radio station in America that was programmed entirely for African Americans.[1] It featured black radio personalities; its success in building an audience attracted radio advertisers suddenly aware of a "new" market among black listeners. The station had a strong influence on music, hiring musicians early in their careers, and playing their music to an audience that reached through the Mississippi Delta to the Gulf Coast. The station started the WDIA Goodwill Fund to help and empower black communities. Owned by iHeartMedia, Inc., the station's studios are located in Southeast Memphis, and the transmitter site is in North Memphis. Contents [hide] • 1 History • 2 References • 3 Further reading • 4 External links History[edit] WDIA went on the air June 7, 1947,[2] from studios on Union Avenue. The owners, John Pepper and Dick Ferguson, were both white, and the format was a mix of country and western and light pop. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

U. S. Radio Stations As of June 30, 1922 the Following List of U. S. Radio

U. S. Radio Stations as of June 30, 1922 The following list of U. S. radio stations was taken from the official Department of Commerce publication of June, 1922. Stations generally operated on 360 meters (833 kHz) at this time. Thanks to Barry Mishkind for supplying the original document. Call City State Licensee KDKA East Pittsburgh PA Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Co. KDN San Francisco CA Leo J. Meyberg Co. KDPT San Diego CA Southern Electrical Co. KDYL Salt Lake City UT Telegram Publishing Co. KDYM San Diego CA Savoy Theater KDYN Redwood City CA Great Western Radio Corp. KDYO San Diego CA Carlson & Simpson KDYQ Portland OR Oregon Institute of Technology KDYR Pasadena CA Pasadena Star-News Publishing Co. KDYS Great Falls MT The Tribune KDYU Klamath Falls OR Herald Publishing Co. KDYV Salt Lake City UT Cope & Cornwell Co. KDYW Phoenix AZ Smith Hughes & Co. KDYX Honolulu HI Star Bulletin KDYY Denver CO Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZA Tucson AZ Arizona Daily Star KDZB Bakersfield CA Frank E. Siefert KDZD Los Angeles CA W. R. Mitchell KDZE Seattle WA The Rhodes Co. KDZF Los Angeles CA Automobile Club of Southern California KDZG San Francisco CA Cyrus Peirce & Co. KDZH Fresno CA Fresno Evening Herald KDZI Wenatchee WA Electric Supply Co. KDZJ Eugene OR Excelsior Radio Co. KDZK Reno NV Nevada Machinery & Electric Co. KDZL Ogden UT Rocky Mountain Radio Corp. KDZM Centralia WA E. A. Hollingworth KDZP Los Angeles CA Newbery Electric Corp. KDZQ Denver CO Motor Generator Co. KDZR Bellingham WA Bellingham Publishing Co. KDZW San Francisco CA Claude W. -

Supplemental Report Form

RECORDKEEPING FORM B-4 SUPPLEMENTAL RECRUITMENT ACTIVITIES UNDERTAKEN BY THE STATION Stations Claiming Credit: WHBQ, WHBQ-FM, KXHT, WOWW, WGSF, WIVG WMPS and WMSO (through Arlington Broadcasting) 1. Type of Activity Under New EEO Rule: Job Fairs Dates of Participation: 3/13/19, 3/20/19, 3/26/19, 9/25/19, 10/23/19, 11/14/19 Participating Employees: Carla Hicks, Mike Brewer, Duane Hargrove, Brandon Sams, Keith Parnell, Kiran Riar Host/Sponsor of Activity: University of Memphis, Southwest Tennessee Community College, National Career Fairs, Lemoyne Owen College Brief Description of Activity: Station representatives provided information about career opportunities at Flinn Broadcasting during Southwest Tennessee Community College’s Macon Campus Career Fair on Thursday, March 13, 2019 from 11 AM to 1:30 PM. Pamphlets about the various stations were presented to attendees, along with job postings and applications. Students took flyers and promotional material, and attendees filled out applications for employment. Station personnel answered students’questions about broadcasting and employment. Flinn Broadcasting representatives provided information about career opportunities during University of Memphis’ Career and Internship Expo on Wednesday, March 20, 2019 from 12 N to 3 PM. Profiles of various stations were presented, along with job and internship postings. Students took flyers and promotional material and filled out applications for employment. Station personnel also answered students’questions about broadcasting and employment. Flinn Broadcasting managers provided information about career opportunities during LeMoyne Owen College’s Fall Career Expo on Tuesday, March 26, 2019, from 10 AM to 1 PM. Profiles of various stations were presented to attendees, along with job postings and applications. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-200720-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 07/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000107750 Renewal of FM WAWI 81646 Main 89.7 LAWRENCEBURG, AMERICAN FAMILY 07/16/2020 Granted License TN ASSOCIATION 0000107387 Renewal of FX W250BD 141367 97.9 LOUISVILLE, KY EDUCATIONAL 07/16/2020 Granted License MEDIA FOUNDATION 0000109653 Renewal of FX W270BK 138380 101.9 NASHVILLE, TN WYCQ, INC. 07/16/2020 Granted License 0000107099 Renewal of FM WFWR 90120 Main 91.5 ATTICA, IN FOUNTAIN WARREN 07/16/2020 Granted License COMMUNITY RADIO CORP 0000110354 Renewal of FM WBSH 3648 Main 91.1 HAGERSTOWN, IN BALL STATE 07/16/2020 Granted License UNIVERSITY 0000110769 Renewal of FX W218CR 141101 91.5 CENTRAL CITY, KY WAY MEDIA, INC. 07/16/2020 Granted License 0000109620 Renewal of FL WJJD-LP 123669 101.3 KOKOMO, IN KOKOMO SEVENTH- 07/16/2020 Granted License DAY ADVENTIST BROADCASTING COMPANY 0000107683 Renewal of FM WQSG 89248 Main 90.7 LAFAYETTE, IN AMERICAN FAMILY 07/16/2020 Granted License ASSOCIATION Page 1 of 169 REPORT NO. PN-2-200720-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 07/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000108212 Renewal of AM WNQM 73349 Main 1300.0 NASHVILLE, TN WNQM. -

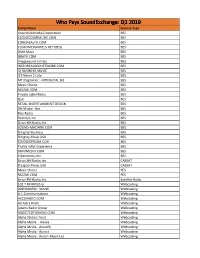

Who Pays SX Q3 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q3 2019 Entity Name License Type AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES F45 Training Incorporated BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It's Never 2 Late BES Jukeboxy BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES Music Maestro BES Music Performance Rights Agency, Inc. BES MUZAK.COM BES NEXTUNE.COM BES Play More Music International BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Startle International Inc. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio #1 Gospel Hip Hop Webcasting 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 411OUT LLC Webcasting 630 Inc Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting AD VENTURE MARKETING DBA TOWN TALK RADIO Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting africana55radio.com Webcasting AGM Bakersfield Webcasting Agm California - San Luis Obispo Webcasting AGM Nevada, LLC Webcasting Agm Santa Maria, L.P. Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting -

Development of the Country Music Radio Format

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/developmentofcouOOstoc THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE COUNTRY MUSIC RADIO FORMAT by RICHARD PRICE STOCKDELL B.S., Northwest Missouri State University, 1973 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Radio and Television Department of Journalism and Mass Communication KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan,;tan, Kansas 1979 Approved by: Major Professor 31 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One . INTRODUCTION 1 A Search of the Literature and the Contribution of this Thesis 2 Methodology » 5 Two . EARLY COUNTRY MUSIC ON RADIO 10 Barn Dances 12 National Barn Dance 13 The Grand Ole Opry 16 The WWVA Jamboree 19 Renf ro Valley Barn Dance 21 Other Barn Dances 22 Refinement of the Music and the Medium 25 Country Music on Records 25 Music Licensing 27 Country Music on Radio 28 Population Migration 29 Country Radio and the War 29 The Disc Jockey 31 Radio Formats Rather Than Programs 32 Three. THE BIRTH OF A FORMAT 34 Why Country Music? 35 Country Disc Jockeys Unite 37 The All-Country Radio Station Ifl David Pinkston and KDAV 47 The Day Country Music Nearly Died 50 Programming the Early Country Stations 55 The Country Music Association 59 ii iii Four. THE ACCEPTANCE AND SUCCESS OF THE FORMAT 63 Refinement of the Format 63 The Marriage of Country and Top /*0 66 Adoption of the Modern Country Format 71 Explosion of the Format „ 76 Advertiser Resistance 78 Bucking the Resistance 81 Audience Loyalty 86 The Final Step 87 Five. -

Licensee Count Q1 2019.Xlsx

Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 2019 Entity Name License Type Aura Multimedia Corporation BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX Music BES GRAYV.COM BES Imagesound Limited BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IO BUSINESS MUSIC BES It'S Never 2 Late BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES Music Choice BES MUZAK.COM BES Private Label Radio BES Qsic BES RETAIL ENTERTAINMENT DESIGN BES Rfc Media - Bes BES Rise Radio BES Rockbot, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES Thales Inflyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES Vibenomics, Inc. BES Sirius XM Radio, Inc CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT Music Choice PES MUZAK.COM PES Sirius XM Radio, Inc Satellite Radio 102.7 FM KPGZ-lp Webcasting 999HANKFM - WANK Webcasting A-1 Communications Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting Ad Astra Radio Webcasting Adams Radio Group Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting Aloha Station Trust Webcasting Alpha Media - Alaska Webcasting Alpha Media - Amarillo Webcasting Alpha Media - Aurora Webcasting Alpha Media - Austin-Albert Lea Webcasting Alpha Media - Bakersfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Biloxi - Gulfport, MS Webcasting Alpha Media - Brookings Webcasting Alpha Media - Cameron - Bethany Webcasting Alpha Media - Canton Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbia, SC Webcasting Alpha Media - Columbus Webcasting Alpha Media - Dayton, Oh Webcasting Alpha Media - East Texas Webcasting Alpha Media - Fairfield Webcasting Alpha Media - Far East Bay Webcasting Alpha Media -

2016 Legacy Nominations

2016 Legacy Nominations Here is a compilation of information about the 2016 Legacy Nominees for induction into the Tennessee Radio Hall Of Fame. This category is voted upon by the Board and Advisory Council of the Tennessee Radio Hall Of Fame. Harry Chapman (1936 New Haven, CT - 2002) RADIO RESUME: 1956-1958 KQUE/KQEO, Albuquerque, NM (Announcer, DJ) 1958-1960 KMGM, Albuquerque, NM (Announcer, DJ) 1960-1962 WYDE, Birmingham, AL (Announcer, DJ) 1962–1964 WMPS, Memphis, TN (Announcer, DJ) 1964–1969 WHBQ, Memphis, TN (Announcer, DJ) 1969-1979 WLOK, Memphis, TN (Sales Mgr) ALSO: • Rock And Roll Promotions 10+ years, Memphis, TN (Owner) • 1966-1970 Showtime Attractions, Memphis, TN (Owner) • 1979–1985 Real Estate Agent, Poplar Pike Realtors, Memphis, TN • 1984-1996 Broker, River Oaks Realtors, Memphis, TN • 1993 MAAR Million Dollar Club Life Member, Memphis, TN • 1996-2002 Broker, Marx-Bensdorf Realtors, Memphis, TN • One of the founders of "Street Tiques" of Memphis • Founding president of the Memphis Mensa Chapter • Member of the Model Railroad Association, Casey Jones Chapter David Earl Hughes (1956 Peoria, IL – 2004) RADIO RESUME: 1976-1979 WRIP, Rossville, GA (Announcer, DJ) 1979-1981 WGOW, Chattanooga, TN (Announcer, DJ) 1981-1991 WSKZ KZ-106, Chattanooga, TN (Announcer, DJ) 1991-2003 WUSY US-101, Chattanooga, TN (Announcer, DJ) 2003-2004 WSM-FM, Nashville, TN (Announcer, DJ) • The KZ-106 Morning Zoo was the top rated morning show in Chattanooga for 5 years. • At US-101: 8 CMA Station of the Year awards, CMA Award for Personality of the Year Medium Market in 1994 & 1999, The Dave and Dex Show was Chattanooga’s the top rated afternoon show.