Development of the Country Music Radio Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Drafting Template

1 State of Arkansas 2 91st General Assembly 3 Regular Session, 2017 SR 13 4 5 By: Senator Irvin 6 7 SENATE RESOLUTION 8 HONORING JIMMY DRIFTWOOD FOR HIS CONTRIBUTIONS TO 9 FOLK MUSIC AND TO THE STATE OF ARKANSAS. 10 11 12 Subtitle 13 HONORING JIMMY DRIFTWOOD FOR HIS 14 CONTRIBUTIONS TO FOLK MUSIC AND TO THE 15 STATE OF ARKANSAS. 16 17 WHEREAS, Mr. Jimmy Driftwood was born James Corbitt Morris in Timbo, 18 Arkansas, on June 20, 1907, and died on July 12, 1998, in Fayetteville, 19 Arkansas; and was a prolific folk singer and songwriter, along with his 20 father, Neil Morris; and 21 22 WHEREAS, Jimmy Driftwood wrote over 6,000 folk songs, and is most 23 famous for “The Battle of New Orleans” and “Tennessee Stud“; and learned to 24 play guitar on his grandfather’s homemade instrument, which he used 25 throughout his career, noting that the neck was made from fence rail, the 26 sides from an old ox yoke, and the head and bottom from the headboard of his 27 grandmother’s bed; and 28 29 WHEREAS, Jimmy Driftwood received a degree in education from Arkansas 30 State Teacher’s College, now the University of Central Arkansas, married 31 Cleda Johnson in 1936, and began writing poetry and music; enjoyed his 32 teaching career in Arkansas and began a family; wrote songs during his 33 teaching career to help teach his students history in an entertaining manner; 34 and wrote his famous “The Battle of New Orleans” in 1936 to help his class 35 become interested in the event; and 36 *KLC253* 03-06-2017 14:08:28 KLC253 SR13 1 WHEREAS, it was not until the -

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected]

BEAR FAMILY RECORDS TEL +49(0)4748 - 82 16 16 • FAX +49(0)4748 - 82 16 20 • E-MAIL [email protected] ARTIST Various TITLE Big ‘D’ Jamboree LABEL Bear Family Productions CATALOG # BCD 16086 PRICE-CODE HK EAN-CODE ÇxDTRBAMy160868z FORMAT 8-CD Box-Set (LP-size) + 168-page hardcover book GENRE Country / Rock ‘n’ Roll TRACKS 285 PLAYING TIME 685:56 G The dawn of rock 'n' roll, like you've never heard it before – live from Texas 1950-1958! G Hear stars like Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent, Wanda Jackson and many more performing live at the dawn of their careers, sometimes singing songs they never recorded! G State-of-the-art live recording for the day. Incredible atmosphere. Fabulous performances! G Unseen photos and newly researched biographies fill out this incredible time capsule! INFORMATION We all know that the Grand Ole Opry wanted nothing to do with rock 'n' roll, while the Louisiana Hayride gave national expo- sure to Elvis Presley, Johnny Horton, and others. Well, the Hayride wasn't alone. The Big 'D' Jamboree in Dallas started with Texas country music but embraced the new music, giving an all-important break to Carl Perkins, Gene Vincent, and many, many more. In a nearly two-decade run that began in the aftermath of World War II, the Saturday night extravaganza packed the Spor- tatorium, a metal wrestling arena in a seedy neighborhood south of downtown. Broadcast locally on KRLD and nationally on CBS radio, the Jamboree was an exuberant cross-section of the most vibrant coun- try and rock 'n' roll music of the time, showcasing everyone from talented but largely forgotten singers such as Riley Crabtree, Orville Couch and Helen Hall to national figures, including Johnny Cash, Sonny James, Hank Locklin, Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Wanda Jackson and Gene Vincent. -

Bluegrass Outlet Banjo Tab List Sale

ORDER FORM BANJO TAB LIST BLUEGRASS OUTLET Order Song Title Artist Notes Recorded Source Price Dixieland For Me Aaron McDaris 1st Break Larry Stephenson "Clinch Mountain Mystery" $2 I've Lived A Lot In My Time Aaron McDaris Break Larry Stephenson "Life Stories" $2 Looking For The Light Aaron McDaris Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 1st Break Mashville Brigade $2 My Home Is Across The Blueridge Mtns Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Mashville Brigade $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Over Yonder In The Graveyard Aaron McDaris 2nd Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Philadelphia Lawyer Aaron McDaris 1st Break Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 When My Blue Moon Turns To Gold Again Aaron McDaris Intro & B/U 1st verse Aaron McDaris "First Time Around" $2 Leaving Adam Poindexter 1st Break James King Band "You Tube" $2 Chatanoga Dog Alan Munde Break C-tuning Jimmy Martin "I'd Like To Be 16 Again" $2 Old Timey Risin' Damp Alan O'Bryant Break Nashville Bluegrass Band "Idle Time" $4 Will You Be Leaving Alison Brown 1st Break Alison Kraus "I've Got That Old Feeling" $2 In The Gravel Yard Barry Abernathy Break Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver "Never Walk Away" $2 Cold On The Shoulder Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On The Shoulder" $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 1st Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 Pain In My Heart Bela Fleck 2nd Break Live Show Rockygrass Colorado 2012 $2 The Likes Of Me Bela Fleck Break Tony Rice "Cold On -

Warburton, John Henry. (2010). Picture Radio

! ∀# ∃ !∃%& ∋ ! (()(∗( Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? John Henry Warburton Master of Philosophy Southampton Solent University Faculty of Media, Arts and Society July 2010 Tutor Mike Richards 3 of 3 Picture Radio: Will pictures, with the change to digital, transform radio? By John Henry Warburton Abstract This work looking at radio over the last 80 years and digital radio today will consider picture radio, one way that the recently introduced DAB1 terrestrial digital radio could be used. Chapter one considers the radio history including early picture radio and television, plus shows how radio has come from the crystal set, with one pair of headphones, to the mains powered wireless with built in speakers. These radios became the main family entertainment in the home until television takes over that role in the mid 1950s. Then radio changed to a portable medium with the coming of transistor radios, to become the personal entertainment medium it is today. Chapter two and three considers the new terrestrial digital mediums of DAB and DRM2 plus how it works, what it is capable of plus a look at some of the other digital radio platforms. Chapter four examines how sound is perceived by the listener and that radio broadcasters will need to understand the relationship between sound and vision. We receive sound and then make pictures in the mind but to make sense of sound we need codes to know what it is and make sense of it. Chapter five will critically examine the issues of commercial success in radio and where pictures could help improve the radio experience as there are some things that radio is restricted to as a sound only medium. -

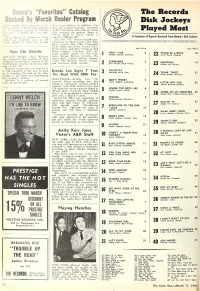

The Records Disk Jockeys Played Most

) ) Dacca’s “Favorites” Catalog The Records Backed By March Bealer Program Disk Jockeys NEW YORK—Deeca Records is of- from local distribs. In addition, win- fering dealers a March sales program dow and counter displays, consumer on its complete catalog of “Golden leaflets and other sales aids are avail- Played Most Favorites,” including nine new addi- able, carrying the general theme of tions. “Every Song In Every Album A A Summary of Reports Received from Nation’s Disk Up to March 24, dealers are being One-In- A-Million Hit.” Jockeys offered an incentive plan on the The new “GF” albums include per- series, details of which can be had formances by Bing Crosby, The Mills lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Bros., Lenny Dee, Ella Fitzgerald, Kitty Wells, Red Foley, Ernest Tubb, Webb Pierce and Kitty Wells & Red Last Week Last Week Foley (duets). Previous “GF” al- New Chi Distrib PONY TIME 2 bums include stints by The Four WINGS OF A DOVE 18 1 Chubby Checker (Parkway) Sams Ferlin Husky (Capitol) CHICAGO—William (Bill) McGuire Aces, Teresa Brewer (Coral), The has announced the opening of Con- Ames Bros., Jackie Wilson (Bruns- Record Sales, located at 101 wick), The McGuire Sisters (Coral) solidated SURRENDER 3 EMOTIONS 19 and Lawrence Welk (Coral). Elvis Presley (RCA Victor) 09 South Cicero Avenue, on the far west 2 MW Brenda Lee (Decca) side of this city. McGuire stated that now that he is in full operation at his new location Brenda Lee Signs 7 Year CALCUTTA 1 Lawrence Welk (Dot) THINK TWICE 31 he is spending the bulk of his time 3 OA Pic Deal With 20th Fox Am *1 Brook Benton (Mercury) calling on the trade and formulating his company’s policies. -

In Country Radio

THEBEST PROGRAM DIRECTORS IN COUNTRY RADIO hey are some of the most important names in Nashville, and across the Country radio fruited plain. They are on a first-name basis with country music’s biggest stars and Nashville’s most important executives. Why? Because radio is still the most important outlet for music to be played and heard, and the PDs on the pages that follow carry around the keys to the radio stations country music fans love most. The relation- tship between country stars, Country PDs, Country radio stations, and the country music fans is like none in any other format. If you’ve ever attended a Country Radio Seminar in Nashville, you know exactly what we mean. The stars mingle with the programmers, great relationships are formed, and a lot of artists and PDs talk or text on a regular basis. And being one of the Best Country Program Directors is much more than mingling with the stars. A successful Country PD has to execute the format flawlessly in markets where there is typically more than one station compet- ing for country fans. A successful Country PD has to have an ear for the music, and be willing to take chances on a new song or new artist. A successful Country PD has to nurture relationships with label executives in Nashville who now have more outlets than ever to get their music to the masses. And a successful Country PD must serve the local community, which is one of the hallmarks, along with strong ratings, of a consistently successful Country radio station. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Texas Ruby Owens

Texas Ruby Owens Ruby Agnes “Texas Ruby” Owens. Country singer born in Wise County, Texas, on June 6, 1910, and died on March 3, 1963. She is buried at Franklin Cemetery in Franklin, Texas. Owens was raised in a musical family with nine sisters and two brothers. One of her brothers, Doie Hensley, went on to country music fame as “Tex” Owens, the radio cowboy. As a young girl, Ruby accompanied her father and brothers on a cattle drive to Fort Worth, Texas. One morning, as they sat waiting at one of the cattle buying centers, she and her brothers began singing some old cowboy songs to pass the time. During this impromptu sing-a-long, a crowd of cowboys and cattle buyers gathered around to listen. Soon, a radio station stock holder from Kansas City, who happened to be in the crowd, offered Owens her first spot on national radio. Texas Ruby, as she came to be called, would be a pioneering figure among female performers within a mostly male-dominated country music industry. Labeled the “Sophie Tucker of the Feminine Folk Singers,” she sang mostly honky-tonk material in a strong, distinct voice and wrote many of her own songs. In 1937, at the Texas Centennial Celebration in Wise County, Texas, Owens met famous “trick fiddler,” Curly Fox (born Arnim LeRoy Fox.) The couple married that same year and formed a popular husband-and-wife team that performed on stage and radio throughout the country and eventually signed with Columbia Records. From 1944 to 1948, the couple appeared frequently at the Grand Ole Opry and were regular stars of the nationally popular Saturday Night Grand Ole Opry. -

Multimillion-Selling Singer Crystal Gayle Has Performed Songs from a Wide Variety of Genres During Her Award-Studded Career, B

MultiMillion-selling singer Crystal Gayle has performed songs from a wide variety of genres during her award-studded career, but she has never devoted an album to classic country music. Until now. You Don’t Know Me is a collection that finds the acclaimed stylist exploring the songs of such country legends as George Jones, Patsy Cline, Buck Owens and Eddy Arnold. The album might come as a surprise to those who associate Crystal with an uptown sound that made her a star on both country and adult-contemporary pop charts. But she has known this repertoire of hardcore country standards all her life. “This wasn’t a stretch at all,” says Crystal. “These are songs I grew up singing. I’ve been wanting to do this for a long time. “The songs on this album aren’t songs I sing in my concerts until recently. But they are very much a part of my history.” Each of the selections was chosen because it played a role in her musical development. Two of them point to the importance that her family had in bringing her to fame. You Don’t Know Me contains the first recorded trio vocal performance by Crystal with her singing sisters Loretta Lynn and Peggy Sue. It is their version of Dolly Parton’s “Put It Off Until Tomorrow.” “You Never Were Mine” comes from the pen of her older brother, Jay Lee Webb (1937-1996). The two were always close. Jay Lee was the oldest brother still living with the family when their father passed away. -

Course Description, Class Outline and Syllabus Instructor: Peter Elman

Course description, class outline and syllabus Instructor: Peter Elman Title: “A Round-Trip Road Trip of Country Music, 1950-present: From Nashville to California to Texas--and back.” Course Description: An up close and personal look at the golden era of American country music, this class will explore key movements that contributed to the explosive growth of country music as an industry, art form and subculture. The first half of this course will focus on three major regions: Nashville, California and Texas, and concentrate on the period 1950-1975. The second half will look at the women of country, discuss the making of a country song and record, look at the work of five great songsmiths, visit the country music of the 1980’s, and end with an examination of Americana music. The course will do this through lectures, photographs, recorded music, film clips, question and answer sessions, and the use of live music. The instructor will play piano, guitar and sing, and will choose appropriate examples from each region, period and style. - - - - - - - - - - - Course outline by week, with syllabus; suggested reading, listening and viewing Week one: The rise of “honky-tonk” music, 1940-60: Up from bluegrass—the roots of country music. Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, Kitty Wells, Lefty Frizzell, Porter Wagoner, Jim Reeves, Webb Pierce, Ray Price, Hank Lochlin, Hank Snow, and the Grand Old Opry. Reading: The Nashville sound: bright lights and country music Paul Hemphill, 1970-- the definitive portrait of the roots of country music. Listening: 20 of Hank Williams Greatest Hits, Mercury, 1997 30 #1 Country Hits of the 1950s, 3-disc set, Direct Source, 1997 Viewing: O Brother Where Art Thou, 2000, by the Coen brothers America's Music: The Roots of Country 1996, three-part, six episode documentary. -

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage

Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Aaron Joseph Johnson All rights reserved ABSTRACT Jazz and Radio in the United States: Mediation, Genre, and Patronage Aaron Joseph Johnson This dissertation is a study of jazz on American radio. The dissertation's meta-subjects are mediation, classification, and patronage in the presentation of music via distribution channels capable of reaching widespread audiences. The dissertation also addresses questions of race in the representation of jazz on radio. A central claim of the dissertation is that a given direction in jazz radio programming reflects the ideological, aesthetic, and political imperatives of a given broadcasting entity. I further argue that this ideological deployment of jazz can appear as conservative or progressive programming philosophies, and that these tendencies reflect discursive struggles over the identity of jazz. The first chapter, "Jazz on Noncommercial Radio," describes in some detail the current (circa 2013) taxonomy of American jazz radio. The remaining chapters are case studies of different aspects of jazz radio in the United States. Chapter 2, "Jazz is on the Left End of the Dial," presents considerable detail to the way the music is positioned on specific noncommercial stations. Chapter 3, "Duke Ellington and Radio," uses Ellington's multifaceted radio career (1925-1953) as radio bandleader, radio celebrity, and celebrity DJ to examine the medium's shifting relationship with jazz and black American creative ambition. -

Power Gold: Concentration Game CMA Sets Trend for Industry

February 10, 2020, Issue 691 Power Gold: Concentration Game This edition of Country Aircheck’s Power Gold is led by eight artists who combine for 46 of the Top 100 most-heard Gold hits. Luke Bryan and Florida Georgia Line lead the parade with seven songs apiece, followed by Jason Aldean and Zac Brown Band with six each. Rounding out the top PG hit-makers are Kenny Chesney, Thomas Rhett, Blake Shelton and Carrie Underwood, all with five hits in the Top 100. One artist – Dierks Bentley – places four songs in this elite group, meaning that nine acts are responsible for 50% of the current Power Gold. More thoughts on that later. Twenty-three songs from 20 artists are new Luke Bryan to the Top 100 since we ran the list last year (CAW 1/14/19). Interestingly, four songs in that group are more than five years old and are actually making a return appearance to the PG 100. They are Tim McGraw’s “Live Like You Were Dying” (2004), Bentley’s “Free And Easy (Down The Staff Hearted: WNCY/Appleton, WI’s Shotgun Shannon, Luke Road I Go)” (2007), Bryan’s “I See You” (2015) and FGL’s “Sippin’ Reid, Charli McKenzie, Hannah, Dan Stone and PJ (l-r) show On Fire” (2015). off the station’s 23rd annual Y100 Country Cares for St. Jude This Top 100 Power Gold – along with the airplay information in Kids Radiothon total. the previous paragraph – is culled from Mediabase 24/7 and music airplay information from the Country Aircheck/Mediabase reporting panel for the week of January 26-Feb.